Global Poverty Reduction and Development Forum-2012-Chapter I

Chapter I: Inequalities in Middle Income Countries: Context, Causes, and Recommendations for Reducing Inequalities

JOHN Taylor

London South Bank University

Addressing rising inequalities within Developing Countries, and more particularly within MICs, has come to be viewed as a major policy challenge in recent years. Policy makers and commentators have reached this conclusion for a number of reasons. They have concluded that the persistence of income inequalities can have an adverse impact on the process economic growth, that this persistence can weaken the poverty impact of growth, and that it can also contribute to economic instability and to economic and social vulnerability. More generally, it has been argued that the persistence of inequalities can contribute to the development of financial crises.

At much the same time that these conclusions have been reached, alongside this we have the increasing influence of the notion of inclusive development, with its emphasis on the need for economic growth to be accompanied by reductions in income inequality and poverty. For inclusive growth, the aim is one of identifying policies that can reduce poverty by fostering both growth and improving income distribution. Additionally, from the viewpoint of the more general aim of inclusive development, there is an additional policy need to address inequalities in access to and use of human capital, since inclusive development additionally requires both overall outcomes in areas such as health and education to improve and inequalities in these achievements to fall. This issue is of particular concern for MICs.

In what follows, in the interests of promoting policies that can contribute to achieving more inclusive forms of growth and development, this chapter of the Report examines the persistence of inequalities within MICs and examines policy options for addressing these inequalities, referring briefly to case study examples of periods during which particular MICs have been able concomitantly to reduce inequalities, achieve growth and reduce poverty levels. The chapter then draws conclusions from this for MICs. The chapter begins by outlining the key component issues of inequality in MICs.

1. Key Issues:

Issue One: A substantial majority of the world’s poor now live in Middle Income countries.

Most of the world’s poor are located in middle, rather than in low-income countries. This is the case whether we measure this in terms of per capita income criteria or in relation to multi-dimensional poverty indicators[1]. It is confirmed in the most recent available poverty estimates[2]. These show that, based on the $1.25 per day line, 74% of the world’s poor live in MICs, and that, based on the $2 per day line, 79% of the world’s poor live in MICs. At MIC country level, based on the $2 line, 35% of the world’s poor live in India, 16% in China, and 28% mostly in Nigeria, Indonesia, and Pakistan. In contrast, less than a quarter of the world’s poor currently live in Low Income Countries. Projecting these figures to 2015 continues these trends[3]

Table 1: Estimates of the distribution of global poverty, and poverty incidence, $1.25 and $2, 2008[4]

|

|

$1.25 poverty line |

$2 poverty line |

||||

|

|

Millions of people |

% world’s poor

|

Poverty incidence (% popn) |

Millions of people |

% world’s poor |

Poverty incidence (% popn) |

|

East Asia and Pacific |

265.4 |

21.5 |

14.3 |

614.3 |

26.1 |

33.2 |

|

Eastern Europe and Central Asia |

2.1

|

0.2

|

0.5

|

9.9

|

0.4

|

2.4

|

|

Latin American and the Caribbean |

35.3

|

2.9

|

6.9 |

67.4

|

2.9

|

13.1 |

|

Middle East and North Africa |

8.5

|

0.7

|

2.7

|

43.8

|

1.9

|

13.9 |

|

South Asia |

546.5 |

44.3 |

36.0 |

1,074.7 |

45.6 |

70.9 |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

376.0 |

30.5 |

47.5 |

547.5 |

23.2 |

69.2 |

|

Low Income Countries |

316.7 |

25.7 |

48.5 |

486.3 |

20.6 |

74.4 |

|

Middle Income Countries |

917.1 |

74.3 |

19.5 |

1,871.1 |

79.4 |

39.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

New MICs (post-2000) |

651.7 |

52.8 |

33.4 |

1,266.4 |

53.7 |

64.9 |

|

LMICs |

711.6 |

57.7 |

30.2 |

1,394.5 |

59.2 |

59.1 |

|

LMICs minus India |

285.6 |

23.1 |

23.4 |

569.4 |

24.2 |

46.7 |

|

UMICs |

205.5 |

16.7 |

8.7 |

476.6 |

20.2 |

20.3 |

|

China and India |

599.0 |

48.6 |

24.3 |

1,219.5 |

51.7 |

53.8 |

|

PINCIs |

785.9 |

63.7 |

26.1 |

1,570.0 |

66.6 |

52.2 |

|

Fragile States (OECD) |

398.9 |

32.3 |

39.9 |

665.4 |

28.2 |

66.6 |

|

Total |

1,233.8 |

100.0 |

22.8 |

2,357.5 |

100.0 |

43.6 |

Table 2: Top 12 countries by number s and percentages of population below $1.25/2.00 per day lines, 2008). (Countries transitioning from LIC to MIC since 1990 are highlighted)[5]

|

|

% World $1.25 Poor

|

% World $2 Poor |

Country classification (based on data for calendar year) |

GDP pc/day (PPP, constant 2005 $) |

||

|

|

2008 |

2008 |

1990 |

2009 |

1990 |

2009 |

|

1. India |

34.5 |

35.0 |

LIC |

LMIC |

3.4 |

8.2 |

|

2. China |

14.0 |

16.7 |

LIC |

UMIC |

3.0 |

17.0 |

|

3. Nigeria |

8.1 |

5.4 |

LIC |

LMIC |

3.9 |

5.6 |

|

4. Bangladesh |

6.0 |

5.3 |

LIC |

LIC |

2.0 |

3.9 |

|

5. DRC |

4.5 |

2.6 |

LIC |

LIC |

1.7 |

0.8 |

|

6. Indonesia |

4.2 |

5.2 |

LIC |

LMIC |

5.5 |

10.1 |

|

7. Pakistan |

2.3 |

5.2 |

LIC |

LMIC |

4.4 |

6.5 |

|

8. Tanzania |

1.4 |

1.6 |

LIC |

LIC |

2.4 |

3.4 |

|

9. Philippines |

1.3 |

1.6 |

LMIC |

LMIC |

7.0 |

9.2 |

|

10. Kenya |

1.2 |

1.1 |

LIC |

LIC |

3.9 |

3.9 |

|

11. Vietnam |

1.1 |

1.6 |

LIC |

LMIC |

2.5 |

7.5 |

|

12. Uganda |

1.1 |

0.9 |

LIC |

LIC |

1.5 |

3.1 |

Despite many countries becoming richer and moving in to MIC status (or moving from lower to upper MIC status), many of these countries still have high levels of poverty. Addressing poverty in many MICS is thus becoming more of a national issue, since many have graduated to a point where they are no longer eligible, internationally, to receive aid[6]

Issue Two: Inequalities are increasing in many Middle Income Countries

Many MICs are characterized by relatively high and growing levels of inequality[7]. In per capita terms, most MICs have levels of inequality substantially in excess of the average of OECD countries, and in many cases, levels of per capita income inequality are increasing. This increase is the case, for example, for a number of large MICs in the Asian region, as illustrated below[8]:

Table3: Gini Coefficients in Selected MICs.

|

Country |

Initial Year |

Final Year |

Gini: 1990s |

Gini:2000s |

|

PR China |

1998 |

2008 |

32.4 |

43.4 |

|

India |

1993 |

2010 |

32.5 |

37.0 |

|

Indonesia |

1990 |

2011 |

29.2 |

38.9 |

In addition to inequalities measured via the use of data on per capita incomes, there is substantial evidence that inequalities continue to persist in other MIC areas, notably in education (measured in net enrolments by wealth quintile) and health (as measured by infant mortality rates per wealth quintile)[9].

Issue Three: Inequalities can Disadvantage Development.

Firstly, the persistence of inequality can have an adverse impact on economic growth. Traditionally, a degree of inequality has often been seen as beneficial by providing incentives for investment and growth. However, in recent years it has become equally clear that in Middle Income Countries persistent inequality can have an adverse impact on growth, resulting from effects it produces such as misallocations of human capital, unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, and a greater risk of instability. Evidence is emerging that longer spells of economic growth are strongly associated with greater equality in the distribution of income, indicating that in the longer-term, sustainability and reduced inequality may be mutually reinforcing[10].

Secondly –as has become strikingly clear in recent years- rising income inequalities are an important causal factor in the onset of financial crises, creating possibilities for macroeconomic instability in Middle Income Countries[11].

Thirdly, the impact of poverty reduction efforts can be weakened as a result of on-going inequalities. Given a particular level of growth, a higher level of inequality leads to less poverty reduction. For example, taking official Chinese Government poverty lines, from 1981-2001, with the same growth rate and no rise in inequality in its rural areas, the number of poor in China would have been less than one quarter that of its actual value –that is a poverty rate in 2001 of 1.5 per cent rather than 8 per cent[12].

Fourthly, the persistence of inequalities may contribute to countries continuing to succumb to the (so-called) Middle Income Trap[13]. Most of the countries that were in the middle income category in 1960 remained so in 2008. Only 13 countries escaped the middle-income trap, becoming high-income economies in 2008. This may be due to unequal distribution of income and assets produced by a continuing reliance on an export-oriented growth strategy, and the perpetuation of this distribution through enabling government policies. The maintenance of this distribution and these policies can then combine to limit the development of an internal market and an overall increase in household consumption that could provide a more sustainable basis for continuing growth.

Consequently, due to its potential outcomes in relation to the fundamental areas of growth, financial stability, poverty reduction and sustainability, inequality in Middle Income Countries is a key policy area, increasingly recognized as such.

2. What Causes Persistent Inequalities in Middle Income Countries?

Since MICs continue to experience relatively high and growing levels of inequality, what are the main reasons for this?

A key factor is the regional impact of economic development, which seems to be particularly uneven in many MICs, with the benefits of development accruing to a relatively greater extent to areas that have strategic, locational, or infrastructural advantages, leading to major shifts in the distribution of income geographically. This is often reinforced by relatively socially or ethnically disadvantaged groups being concentrated in particular areas[14]. More generally, this applies to urban-rural income gaps, and to regional gaps which have been widening in many MICs during the last decade[15]. This is particularly the case with India and China, for example, where rural-urban and regional gaps have increased substantially[16], but they are also a strong contributor to inequality in Indonesia and Vietnam. In China, the gap between urban regions in the west and east is widened by a substantial 25% from 2002-7. Combining spatial and rural-urban inequalities and calculating them as a percentage of overall inequality reveals extremely high levels, of 53% in China, 36% in Vietnam, and 32% in India[17]. The only MIC in which the rural-urban gap has not increased in recent years is Brazil, with average per capita incomes in rural areas increasing more rapidly than those in urban areas since the mid1990s.

A key contributory factor to spatial inequality is the persistence of inequalities in access to education, which is also a major contributor to income inequality in Middle Income Countries. Although primary enrolment rates in many MICs now approximate those in high income countries, they vary considerably internally between different groups and regions, with rural areas in general performing less well than urban areas, and girls remaining disadvantaged. These trends are intensified at the secondary level. In Pakistan, for example, in 2008, net attendance in primary education for the top quintile was approximately twice that of the bottom quintile. At the secondary level, the ratio was over five, and for post-secondary 27. Recent household survey data from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) conclude that educational inequality accounts for more than 20% of total income inequality in a selected eight of the Asian region’s MICs[18]. Additionally, the share of inequality accounted for by differences in educational attainment increased in all Asian MICs from 1995-2007[19], with China recording a substantial increase, from 8.1 to 26.5 per cent.

Increases in income inequality may also be related to technological development requiring more skilled labour, with a resulting differentiation in wage levels between skilled and less skilled/unskilled workers affecting income distribution. This can then be reinforced by growing inequalities between regular and contractual workers. The growth in earnings inequalities has been marked in major MICs in recent years: in China the earnings in the top decile now are 5 to 6 times higher than those in the bottom decile; the figure for India is 12 (a doubling since the early 1990s) and for South Africa a massive 26[20].

Alongside these inequalities in earnings, there has been a significant decline in the share of income accruing to labour rather than to capital since the early 1990s, with all MICs showing declines in labour shares since the early 1990s[21]. One (fairly obvious) reasons for this is in some MICs is technological change increasing productivity (and hence producing higher returns to capital relative to labour), but the relative decline is also the result of the impact of the 2008 financial crisis having widely differing results for economic groups, and of an on-going process of rent-seeking[22] –promoted by government policies providing relatively low taxation levels on wealth, capital gains and profits, enabling some economic elites to benefit disproportionately. In China’s case, for example, increases in inequality in recent years have been fuelled by its post-2001 exports boom leading to a boom in profits feeding into speculative bubbles in housing and real estate, enabled by limited checks on capital flows into these areas.

Despite overall improvements in average levels, inequalities in access to health facilities remain prominent in MICs. These are reflected most strikingly in differential quintile infant mortality rates and in urban-rural mortality rates. All MICs in Asia, for example, have higher mortality rates for the bottom quintile and for rural areas[23]. Access remains unequal. For example, a recent (2008) assessment of poor households in 11 provinces in China found that illness remained untreated for financial reasons in 57.9% of the sampled population[24]. Similarly, a more recent (2009) survey of poor villages concluded that of those households returning to poverty, 43.8% did so as a result of increasing health costs[25]. Several large MICs have health expenditure levels below the average 5.7% of GDP average for MICs, notably India at 4.1% and Indonesia at 2.6%. This similarly is reflected in per capita (PPP) expenditures, with an MIC average of $369, and India at $132, with Indonesia at $112 [26].

3. Addressing Inequalities in MICS: Policy and Practice: Case Studies

In order to develop recommendations for relevant policies to address growing levels of inequality, it is useful to look briefly at the experiences of MICs that have succeeded in reducing high levels of inequality, and to try to specify the reasons for this.

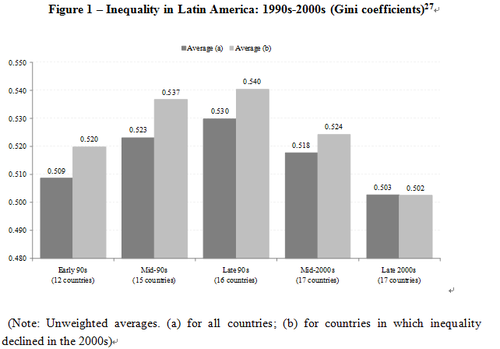

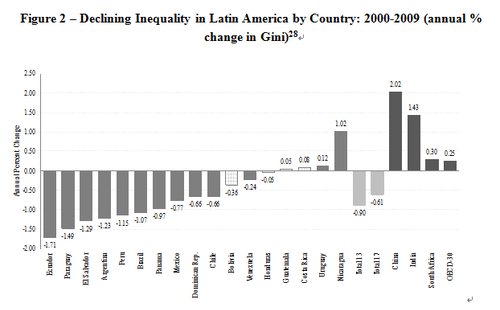

During the 1980s and early 190s, income inequality increased in most Latin American countries. However, commencing in the mid-1990s, and particularly in the first decade of the 21st century, income inequality began to decline –at the very time when it was increasing in other MICs. The caveat, of course is that, despite this decline, inequalities still remain high, but nonetheless the significant reduction is worthy of examination.

The changes in inequality, measured in terms of per capita incomes, and specified in gini coefficients, are presented in Figure I, below:

Table Four: Gini Coefficients for Selected Latin American Countries[29]

|

Gini Coefficients |

1990 |

2002 |

2006 |

2010 |

|

Argentina |

0.501 |

0.590 |

0.510 |

0.445 |

|

Brazil |

0.627 |

0.621 |

0.602 |

0.547(2009) |

|

Chile |

0.554 |

0.550 |

0.522 |

0.521(2009) |

What were the reasons for these declines?

For Latin America overall, the external trading environment undoubtedly became more favorable. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the growth of China and other Asian countries has had a marked effect on both imports and exports. Regional export/GDP ratio increased from 13-26% from 1995-2007, benefitting largely from substantial increases in commodity prices. Additionally, external financing became increasingly available. From 2004-7, for example, Latin America experienced a substantial increase in capital inflows, mostly portfolio inflows into the private sector, in purchases of shares and securities in regional stock markets[30]. Both these factors contributed to a strong economic recovery, with many Latin American countries improving their growth rates in the first decade of the 21st century (Brazil currently has a 7.2% GDP growth rate and Argentina 9.2%)[31] This created an enabling environment for reducing poverty and inequality, but of greater interest is what was occurring in the more successful countries during this period. This can be assessed by looking briefly at the cases of Argentina and Brazil.

In the case of Argentina, the major reason for the decline in household per capita income inequality –agreed by almost all analysts- is a reduction in labour (earned) income inequality, responsible for almost 70% of the total inequality decline. This seems to have been due to the expansion in unemployment attendant upon Argentina’s substantial increases in growth rate, an increasing focus on the skill of workers, resulting in them forming a larger part of the labour force, (thereby reducing the earlier “skills premium” accruing to a relatively smaller number of workers, as in the late 1990s), and a strengthening of the power of the country’s trade unions. However, also of importance was a substantial expansion of poverty reduction programmes –particularly the implementation of large targeted cash transfer programmes, most notably the post 2002 Jefes y Jefas de Hogar Escupados (Programme for Unemployed Male and Female Heads of Households)[32], with its focus on female-headed households receiving cash transfers in return for work in microenterprises, returning to education, vocational training, and on community-based projects. The programme covers 2 million and accounts for 5% of the National Budget. According to UNDP estimates, the programme contributed substantially to the country’s rapid poverty reduction, from 9.9% in 2002 to 4.5% in 2005.

In Brazil, similar factors are at work as in the Argentinian case, with reductions in wage inequality, but this notably –and to a greater extent than Argentina- being associated with a reduction in educational inequality, particularly at the primary and secondary levels. For example, overall educational inequality declined from 0.45 in mid-2002 to 0.441 in mid-2007. Regional inequalities appear to have declined due to reductions in wage labour differentials between metropolitan and municipal areas[33]. Public transfers were also important, notably via the increasing coverage of targeted conditional cash and cash transfer programmes such as the well-known Bolsa Familia and Beneficio de Prestacao Continuada (Brazilian Pension Program).

In both Brazil and Argentina, common factors seem to be at work:

In the early years of the 21st century, workers with skills began to comprise a larger share of the labour force than in the 1990s, as the skills premium declined. Hence earnings inequality also declined. Most importantly, however, this process was enabled and reinforced by educational upgrading of less skilled and unskilled workers. We clearly have a case of improved access to education reducing educational inequalities and this then feeding through into reductions in income inequality.

Cash transfers also played an important role in addressing inequality levels. For example, in the period 2000-7, with an increasing emphasis on re-distribution, fiscal policy in Argentina reduced the market income gini coefficient by 4.8 percentage points. However, when in-kind transfers (imputed values for public education and health) are included in the calculation, fiscal policy reduced net market income gini by 12.8 percentage points in Argentina[34]. Additionally, cash transfers reduced extreme poverty by a substantial 63%[35]. Similar conclusions can be reached with regard to Brazil’s cash transfer programmes: For example, a study carried out in 2006 decomposed the inequality reduction observed in Brazil from 2000-6, and concluded that government cash transfers (in the pension programme and in Bolsa Familia accounted for one third of the decline.

The substantial increase in the use of large-scale cash transfers targeted to the poor was made possible by both increases and changes in the structure of social expenditure. Overall levels of social expenditure increased in Latin America from the mid-1990s onwards and Brazil and Argentina reached social expenditure/GDP ratios of between 15 and 20 per cent during this period, a figure which is close to the OECD level. Within this increase, changes in the structure of expenditure were important, with most of the increase occurring in the areas of social security, social assistance and education[36].

Finally, it is also important to note the fundamental changes occurring in tax policy, particularly since 2002, since these provided revenue for the growth of the cash transfer programmes. The changes were characteristic of Latin America overall, with tax and non-tax central government revenue contributions increasing from 15 to 17 per cent, 1990-2000, and then to 20.2 per cent in 2007. This was particularly the case in Brazil and Argentina, with revue increases of nine points in GDP from 2002-7. Whilst this was due to the much publicised “windfall” taxes from the increase in world commodity prices, it should also be noted that it resulted from a broadening of the tax base, an increase in direct taxes –in personal and corporate taxes, in indirect taxes (largely in VAT), and from major attempts at reducing evasion. By 2006, Brazil and Argentina had reached tax levels similar to those of major OECD countries such as Japan and the United States. These increases in revenue also co-existed with reductions in external debt, with both Argentina and Brazil paying their outstanding debts to the IMF.

Assessing the cases of two Middle Income Latin American countries during the first decade of the 21st century provides some evidence for the conclusion that reasonable GDP growth, reductions in inequality and reductions in poverty levels can be achieved concomitantly, under particular conditions. Achieving this combination is essential for meeting the requirements of a relatively more inclusive growth (as defined, for example by McKinley[37]) and –if we add the achievements in reducing educational inequality- for the beginning to attainment a more inclusive form of development (as defined by Kanbur et al[38]).

Based on the assessment of the Latin American MICS, and introducing some findings from conclusions reached on the growth-inequality-poverty inter-relation in other MICs, what particular changes in which policy areas can be recommended as possible contributions to the achievement of reductions in inequalities currently prevalent in MICs, and to the attainment of more inclusive forms of growth and development than those currently prevalent in MICs?

4. Reducing Inequalities: Policy Areas for Consideration.

Addressing Regional Inequality

MIC case studies referred to earlier highlight the importance of spatial differentiation in contributing to the persistence of inequalities. In addition, but more generally, a recent study by the ADB concludes that in the Asian region, 30-50% of income inequality is due to uneven growth[39]. Addressing spatial inequalities successfully also seems to be related to successful movement from middle to high income status.[40] As countries become more developed, disparities attributable to location diminish, particularly in relation to welfare. A (2009) World Bank study partitioned selected countries each into five areas, and measured their spatial welfare disparities; Bangladesh and Cambodia, both with GDP per capita less than $300 (in 2000) had spatial gaps between their leading and most backward areas of 89 and 73per cent respectively; For Colombia and Thailand (per capita GDP $2,000) the equivalent gaps are approximately 50 per cent; For Canada (GDP per capita $20,000, the gap is less than 25 per cent[41].

The problem with addressing spatial inequalities lies in the rather obvious point that both these inequalities and the reasons for them differ markedly between MICs. For example, whilst in India differences reflect imbalances between states, in China inequalities stem more from differences within provinces, and in South Africa, where as a result of the apartheid period, geographical divisions correspond to a considerable extent with ethnic and racial inequalities. As is well known, spatial inequalities can be reinforced by strategies requiring the development of export-oriented production zones in areas which are already reasonably well endowed -a notable characteristic of Latin American development in the 1970s and 1980s, an of China particularly during the 1990s. Key features of disadvantaged regions are their lower levels of human capital, infrastructure, and access to social and public services. To address these, two over-riding areas seem most important: fiscal transfers from wealthier to poorer regions and the development of meaningful regional growth strategies. Of particular interest here for MICs is, of course, the Chinese Government’s strategy for developing its western provinces, assessed by several studies as contributing to increase in growth for the 11 provinces covered, and to overall reductions in inequality from 2004 onwards, following its introduction in 2000[42]. The strategy focused largely on infrastructure development in key areas (such as power, transport and telecommunications), but central to it was substantial fiscal transfers from the central government, thereby enabling subsequent increases in foreign direct investment. In an earlier period, during the late 1970s, Malaysia began to address its widening poverty rates between states by fiscal transfers, targeting particularly health and education. Since the early 1980s, the percentage difference between maximum and minimum state poverty rates has declined from 60 to 18 percent[43]. There are also important cases of MICs specifically targeting areas of regional inequality via specific welfare programmes, based on changing patterns of fiscal transfer. In the health area, for example, In Indonesia, the coefficient of variation for average learning across provinces declined from 0.43 in 1971 to 0.15 in 2000[44]. Similarly, in Thailand infant mortality rates narrowed from a minimum-maximum gap of 6 percentage points between the leading and least developed in 1980 to 0.7 percentage points in 200, due to targeted fiscal transfers[45].

Tackling Inequalities in Health and Education

As noted earlier, government spending on health and education can assist in reducing levels of inequality in these areas. In addition to what we have already outlined, a recent comparative panel estimate of 150 countries, covering the period 1970-2001, concludes that increased expenditure on education and health reduces gini coefficients significantly[46]. This is consistent with the findings from the two case studies of Brazil and Argentina. With levels of expenditure on education at less than 4% in India, China and Indonesia, and on health at less than 5% (compared with the OECD averages, respectively, of 5.2% and 9.4%), the need to increase spending on these areas in MICS is clear –and the scope for this exists, given recent growth rates. However, the key issue here is that of targeting –even if health and education facilities are available, poor households may not be able to afford to use them. Hence the importance of programmes such as conditional cash transfers, as seen in the cases of Brazil and Argentina, where they have had considerable success in improving attendance by poor household members.

Conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes have been implemented in other MICs, such as South Africa, Nigeria and Indonesia, but they have yet to be introduced to any substantial extent in India and China[47]. It is important to note, however, that despite much enthusiasm for CCTs –and particularly for their ability to reach poor households and reduce inequalities in the short-term, the evidence that they actually improve health conditions sustainably, in the longer-run, is rather more mixed. For example, whilst CCTs increase the likelihood of children from poor households attending clinics for health checks, this does not always lead to improved nutritional status for children[48]. Additionally, recent evidence suggests that in some cases, notably in CCTs in Bangladesh, the targeting criteria used effectively exclude significant groups within the poor population[49]. Improvements could be made in this area via a more extensive use of targeting based on indicators in the multidimensional poverty index, as was the case recently in Ghana’s recent implementation of CCTs in encouraging primary school attendance.

Changes in Fiscal Policy

Addressing inequalities regionally and in areas of human capital could put upward pressure on government expenditure, hence the need for additional revenue to finance both these tasks, and to fund social protection schemes, assessed below. Achieving increased revenue may well require major changes in fiscal policy in MICs, as evidenced in the Brazilian and Argentinian case studies. The main issue here is how best to do this in ways that can both increase growth and promote redistribution, thereby attempting to reduce inequalities. The Brazilian case highlights the importance of tax simplification, and of widening coverage to try and include more of the informal sector. The Latin American cases also provide examples relevant for other MICs, particularly the importance of balancing revenue from personal income tax and property taxes with taxes on consumption. Achieving an improved balance, from consumption to income tax enables taxation to become less regressive and facilitates addressing income inequality. This is particularly the case in an MIC such as India, where the percentage of the population paying income tax has remained low –at 2-3 per cent in recent years. Whilst it is clear that changes in taxation –addressing the informal sector, evasion and promoting a more progressive system can contribute both to increased revenue and to enabling a reduction in income inequality, the problem here is that successfully implementing such changes takes time, and often encounters political resistance –particularly when revenues can be more easily increased in the short-run through increasing taxes on the raw material export sector, as can be done in resource dependent MICs. Given this time constraint, perhaps in the short-run, in addition to CCTs, inequality can be addressed more adequately by carefully targeted social welfare and protection programmes.

Improving Social Protection

Despite considerable evidence of the importance of social protection programmes in reducing inequality -in addition to their vital role in meeting the needs of poor households and in dealing with transitory poverty, both the coverage and amount spent on these programmes is far less in most MICs when compared with high income countries.

Whilst some MICs such as Brazil and Russia have spent approximately 15-20 per cent of their GDP on social protection programmes, others such as India and China have spent far less, averaging 5-7% in recent years. By contrast, OECD countries devoted an average 20% of their GDP to social protection in 2007[50].

Coverage in MICs is highly variable. For example: Brazil has a comprehensive social insurance scheme financed by contributions, covering old-age pensions, maternity, disability and safety at work, together with an unemployment insurance scheme. In contrast, India has very limited coverage, providing a degree of health insurance and maternity benefits to higher paid employees, numbering only almost 9 million; apart from a small number of additional contributory schemes run by state governments, there remain only very limited employment programmes and basic food subsidies.

Unemployment schemes in MICs tend to focus on basic severance payments, with much lower levels of support for on-going unemployment insurance. One of the major reasons for the limited support for unemployment insurance is the high level of employment in firms that do not pay minimum insurance contributions, and the refusal of firms to meet severance pay commitments[51]. Eligibility qualifications are also excessively high in some MICs. For example, In India workers have to contribute for a minimum of five years before receiving any payments. Relative to the number of employed, the number of recipients also tends to be low –only 10 per cent, for example, in South Africa and China[52].

In addition to CATs –as outlined earlier, additional non-contributory programmes in MICs are food, public works, labour and job creation programmes. As is well known, India has the largest public works programme, covering almost 10 per cent of the labour force. A further example is Indonesia, whose job creation programmes employed an average of approximately 5% of the labour force from 2000-2006[53].

In assessing how social protection programmes can be improved, we have already outlined the roles that can be played by CCTs, and the ways in which access to education can be made more equitable. A further key area of social protection, however, remains -namely policies relating to employment and unemployment.

Increasing the coverage of unemployment compensation schemes to anything like the level prevalent in high income countries in MICS will take considerable time, given the levels of expenditure required, and the added problem of attempting to incorporate the substantial numbers of those working in the informal (and migrant) sectors. As noted earlier Brazil has relatively generous unemployment compensation, which also has a relatively high level of coverage. Key features of this are worthy of consideration in other MICs. Most notable are its specific levels of targeting: income support targets workers who are dismissed unfairly, or those who have lost their jobs due to closure. It also focuses on those workers from households with the greatest need –based on an assessment of the funds currently available at the time of dismissal. Additionally, support continuing is conditional upon evidence that the unemployed are actively seeking employment. These issues would seem to be relevant for MICs attempting to extend unemployment compensation schemes with limited levels of social expenditure; once established, eligibility can be extended, but in initial years, this may be an appropriate way of proceeding.

In relation to social protection and employment, minimum wage policies are vitally important, particularly since redistributing income to workers at the lower end of the wage scale reduces dispersion and (hopefully) contributes to increasing levels of demand. In the cases of Brazil and Argentina ensuring a minimum wage in the formal sector also then fed through into the informal sector. Currently, levels of minimum wage coverage are relatively low in the large MICs, India and China, where the minimum wage itself is also low, relative both to other MICs and to high income countries: for example, the minimum wage in India is approximately 21% of the average wage, and in China, approximately 24%. Since these figures are overwhelmingly for the urban sector, have virtually no influence on the informal and have little relevance for the rural sector, the case for increasing these is clear, particularly given the redistributive impact in relation to existing levels of inequality.

Thus far, we have suggested ways in which social protection programmes can be improved, by focusing on particular programme areas. A key problem for MICs, however, is that many of the programmes implemented are fragmented, being characterised by limited levels of co-operation and co-ordination. Generally, there is limited co-ordination between social insurance and social assistance programmes. Within programmes themselves, co-ordination is also limited. In the pensions sector, for example, there are often different, overlapping and uncoordinated programmes for different groups –workers in the rural sector, public employees, and private sector workers. Consequently, consideration could be given to reducing fragmentation by promoting a greater degree of integration and harmonisation[54]. This can enable improved performance and overall provision of social protection. For example, combining health insurance with pension provision can provide improved incentives to save for later years. Combining longer-term savings with savings for unemployment benefits can better protect workers during economic recessions. Combining programmes can also result in a saving of scarce resources, resulting in more efficient financing and management.

Levels of co-operation and co-ordination between and within MIC social protection programmes can be assessed by examining levels of development and coverage of individual programmes, and by examining levels of co-ordination and integration across programmes. Initially it may be possible to integrate programmes with similar objectives. Beyond this, programmes can be co-ordinated to a greater extent in relation to their mandates, the instruments they use, their financing mechanisms, and their institutional arrangements. The aim is, broadly, to develop co-ordination based on promoting greater inclusion, and –hopefully- through this, increased levels of equity of provision. Improving co-ordination can thus be beneficial for most MICs, even though they have different levels of social protection. This point can be illustrated by citing the cases of India and China.

As is well known, India’s social protection coverage is low, being focused primarily on trying to address chronic poverty. This is attempted largely via food programmes and basic support, mostly targeted at rural areas. For example, 50 per cent of the 2 per cent of GDP spent by the Indian Government on protection programmes is spent on the provision of food and fuel subsidies. Other government social protection programmes are very limited, providing for example, support for rural housing, school meals and subsidies for health insurance. These programmes are generally unrelated and there exists very limited co-operation or co-ordination between them. Under these conditions, improved integration could produce a more coherent system which would enable coverage to be increased. For example, it might be beneficial to design and introduce an overall cash transfer programme, which could then become a basis from which additional programmes could be developed, such as pensions provision for low-income workers via social insurance based on government subsidised long term savings. These could also be related to enhanced provision of microfinance for the beneficiaries of the transfers and savings programmes. In recent years, the Indian Government seems to be moving somewhat in this direction, by focusing more on support through cash rather than food-based initiatives, possibly joining cash transfer programmes with pre-existing pension programmes, and enabling the beneficiaries of cash transfers to become employed in public works programmes via establishing improved links between these.

In contrast with India, China has a greater range and coverage of social protection programmes –in areas such as pension provision, medical insurance, unemployment, minimum subsistence, and educational subsidies. However, these programmes vary in coverage and amount between rural and urban areas, and within provinces, and are similarly variable in providing protection for those groups with the greatest needs. For example, in 2010, urban di bao (minimum subsistence) payments were more than double rural di bao payments; pensions levels are lower in rural areas, and they also vary considerably between municipalities; the on-going use of the hukou (residency) system restricts migrant’s access to social and welfare sources. As is now widely acknowledged, to address such problems, social protection provision needs to become more equitable and portable. Meeting this need can be facilitated by improving levels of co-ordination and integration. For example, China currently has separate medical insurance systems covering urban employees, urban non-employees, rural residents, and rural and urban residents in financial difficulties. These are designed separately, with separate and largely independent management and monitoring systems, and only cover 29% of the country’s 150 million migrant workers. Under these conditions, the case for greater harmonization and more extensive coverage is clear, not only in the interests of more efficient management, but also to address the inequalities persisting as a result of the current hukou system. Similarly, in the pensions field, urban residents are enrolled in a variety of schemes, whilst in rural areas local governments pay a (variable) basic pension. Currently only approximately a quarter of migrants have pension coverage (compared with 80% of urban workers), and approximately 35% of rural workers participate in pension schemes[55]. There are many different pension schemes –for public service unit employees, civil servants, urban and rural residents and migrants. These are segmented and do not allow for movement between sectors. There also seem to be strong differences in worker compensation, and limited transparency. There is no portability across rural, urban workers, public sector unit, and urban residents’ schemes[56]. Under these circumstances, a greater degree of integration would be beneficial; initially, for example, working on a greater integration of policy framework and management for the public service unit, civil servant and urban workers schemes, and extending the limited integration of rural and urban residents schemes already commenced in Beijing, Shanghai and Zhongshan. Greater integration of schemes could then establish a basis for higher level pooling, and for improved exchange of information on financing and beneficiaries. Both these would then facilitate a major aim, of achieving greater portability, but would also enable greater equity of provision. Additionally, improving co-ordination and enhancing integration in areas such as the provision of safety-nets, medical insurance and pension provision could facilitate improved security, contributing to increased confidence amongst households to reduce their high savings rates and increase their consumption -thereby improving demand levels to assist in the current process of rebalancing of the Chinese economy.

Summary:

Summarising, the main policy areas for consideration in tackling persistent inequalities in MICS are:

1) Formulating and implementing comprehensive regional growth strategies emphasizing infrastructure development and co-ordinated interventions to strengthen the power, transport and telecommunications sectors. Fiscal transfers encouraging both national and foreign direct investment should accompany these strategies. Such transfers should be targeted specifically to the areas of health and education.

2) Substantially increasing expenditure on human capital in the areas of health and education -under MIC growth conditions in which this has become increasingly possible in recent years. Policies for these increases should be accompanied by specific and detailed targeting of poor communities and households, with cash transfers as a key vehicle for achieving success in this field. Further policies for achieving the sustainability of cash transfer outcomes are crucial, since evidence shows this to be a key problem area in MICs.

3) Changing and developing fiscal policy to simplify taxation systems and extending coverage, notably to relatively large informal sectors, whilst also shifting the balance from consumption to income, thereby facilitating a more progressive approach.

4) Promoting crucial changes in the provision of social protection. Within the overall framework of increasing substantially current levels of social expenditure, and improving the coverage of programmes, there needs to be an improvement particularly in unemployment compensation schemes –increasing coverage and more careful targeting to provide compensation for those in greatest need. Similarly, minimum wage levels can be increased. Fragmentation is a vital issue to be addressed. However, a crucial problem here is that the causes of fragmentation of provision vary considerably between MICs, and so need to be addressed in different ways, depending upon existing coverage levels. As noted above, in the Indian case integration could be enhanced by designing and introducing an overall cash transfer programme, which could then become a basis from which additional programmes could be developed, such as pensions provision for low-income workers via social insurance based on government subsidised long term savings. By contrast, in China, with its higher level of coverage, the problems of limited movement and strong differences between sectors, and limited portability and transparency in provision could be addressed by promoting a greater integration -initially and most importantly in the management of its fragmented safety net, medical and pension programmes, and by extending the existing limited integration of rural and urban residents’ schemes.

Bibliography of Texts Cited

Asian Development Bank (ADB) (2012), Asian Development Outlook 2012: Confronting Rising Inequality in Asia, ADB, and Manila.

Berg, Andrew G. and Osprey, Jonathan D, (2011), “Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin?” IMF, Washington D.C.

Berg, Osprey and Zettelmeyer (2008), “What Makes Growth Sustained?” IMF Working Paper 08/59, IMF, Washington D.C.

Chandy, Laurence and Geertz, Clifford (2011), “Poverty in Numbers: The Changing State of Global Poverty from 2005 to 2015”, The Brookings Institution, Washington DC.

Claus, Iris, Martinez-Vazquez, Jorge, Vulovic, Violetta, Government Fiscal Policies and Redistribution in Asian Countries, International Center for Public Policy Working Paper 12-13, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University.

Cornia, Giovanni Andrea (2009), “What explains the recent decline of income inequality in Latin America”, draft paper presented to The Conference on the Impact of the Financial Crisis in India, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, March 2009.

Fan, S., R. Kanbur, and X. Zhang, (2011), “China’s Regional Disparities: Experience and Policy”, Review of Development Finance, 1 (1).

Fan, S., R. Kanbur, and X. Zhang (eds.), (2009), Regional Inequality in China: Trends, Explanations and Policy Responses. Routledge, London and New York.

Fiszbein, Ariel, and Schady, Norbert (2009), Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Present and Future Poverty, World Bank Policy Research Report, Washington D.C.

Gill, I and Kharas, H (2007), An East Asian Renaissance: Ideas for Economic Growth, World Bank, Washington. D.C.

Hill, H, Resosudarmo, B, Vidyattama, Y, (2007), “Indonesia’s Changing Economic Geography”, Working Papers in Economics and Development Studies, 2007-13,Bandung, Indonesia.

Kanbur, Ravi and Raunyar, Ganesh, (2009), “Conceptualizing Inclusive Development: With Applications to Rural Infrastructure and Development Assistance”, Asian Development Bank, Occasional Paper No.7, ADB, Manila.

Kostzer, Daniel (2008), Argentina: A Case Study on the Plan Jefes y Jefas de Hogar Desocupados, or the Employment Road to Economic Recovery, UNDP Buenos Aires.

Li, S, Luo C, (2011), Introduction to Overview: Income Inequality and Poverty in China, 2002-7, CBI Working Paper 2011-10, Department of Economics, University of Western Ontario, Canada

Li Xiaoyun, (2010), China: Rural Statistics 2010, China Agricultural Press, Beijing.

Lustig, N, et al. (2011), “The Decline in Inequality in Latin America: How Much, Since, When and Why”, Working Paper no.118. Tulane University, Canada.

Lustig, Nora (2011), “Fiscal Policy and Income Redistribution in Latin America: Challenging the Conventional Wisdom”, Society for the Study of Economic Inequality, November, 2011.

Lustig, Nora (2011), “Markets, the State and Inclusive Growth in Latin America: Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and Peru”, UNDP.

McKinley, Terry (2010), Inclusive Growth Criteria and Indicators: An Inclusive Growth Index for Diagnosis of Country Progress, Asian Development Bank, Sustainable Development Working Paper 14, Manila.

Ocampo, Jose Antonio (2007), “”The Latin American Boom”, Revista de Ciencia Politica, Volume 28, no.1.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2011), Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising, OECD, Paris.

Ravallion, M, and Chen, 2 (2004), China’s (Uneven) Progress Against Poverty, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3408, World Bank, Washington D.C.

Robalino, David, A, Rawlings, Laura, Walker, Ian (2012), Building Social Protection and Labor Systems: Concepts and Operational Implications, Social Protection and Labor Discussion Paper No.1202, World Bank, Washington D.C.

Slater, Rachel and Farrington, John (2009), Cash Transfers: Targeting, ODI Project Briefing, Overseas Development Institute, London.

Stiglitz, Joseph E, (2010), Freefall: America, Free Markets and the Sinking of the World Economy, Norton, New York.

Stiglitz, Joseph E, (2012), The Price of Inequality, Allen Lane, London.

Sumner, Andy (2012), “Global Poverty and the ‘New Bottom Billion Revisited: Exploring the Paradox that Most of the World’s Extreme Poor No Longer Live In The World’s Poorest Countries”, Working Paper, May 2012.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Human Development Report 2010: The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development, UNDP, New York.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Human Development Report 2011: Sustainability and Equity: A Better Future For All, UNDP, New York.

Wisaweisuan, N,(2009) “Spatial Disparities in Thailand: Does Government Policy Aggravate or Alleviate the Problem”, in Reshaping Economic Geography in East Asia, Yukon Huang and Alessandro Magnoli Bocchi, World Bank, Washington D.C.

World Bank (2010), Indonesia Jobs Report: Towards Better Jobs and Security for All, Washington D.C.

World Bank (2012) World Development Indicators, World Bank, Washington D.C.

World Bank (2006) World Development Report 2006: Equity and Development, World Bank, Washington D.C.

World Bank (2009), World Development Report 2009: Reshaping Economic Geography, World Bank, Washington D.C.

[1] These indicators comprise the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), as specified in the UNDP Human Development Reports for 2010 and 2011.

[2] These are to be found in the 2012 PovCal data. See PovCalnet World Bank Development Data Group 2012.

[3] See Chandy, Laurence and Geertz, Clifford (2011), “Poverty in Numbers: The Changing State of Global Poverty from 2005 to 2015”, The Brookings Institution, Washington DC.

[4] Source: This table is taken from Andy Sumner (2012), “Global Poverty and the ‘New Bottom Billion Revisited: Exploring the Paradox that Most of the World’s Extreme Poor No Longer Live In The World’s Poorest Countries”, Working Paper, May 2012. (Data for this table were processed from PovCal (2012). Note: PovCal adjusts base years using linear interpolation. PINCIs = Pakistan, India, Nigeria, China and Indonesia. Fragile States = 45 countries in OECD (2011), Divided We stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising, OECD Paris.

[5] Data from Andy Sumner (2012), above. Data used in the table is processed from PovCal (2012) and World Development Indicators 2012

[6] This conclusion raises difficult questions for development assistance. For example: What policies should best be pursued to most adequately address a situation in which there are more poor people in eight states of MIC India than in the 26 countries of Sub-Saharan Africa?

[7] For example, amongst Upper MICs, South Africa has an extremely high gini coefficient of 63.1, Brazil stands at 54.7 and Colombia 55.9. Amongst Low MICs, Angola records 58.6 and Bolivia 56.3. Data are taken from the World Bank World Development Indicators, 2012.

[8] Data taken from Asian Development Bank (ADB) (2012), Asian Development Outlook 2012: Confronting Rising Inequality in Asia, ADB Manila, p.47.

[9] For detailed evidence, see ADB (2012), Asian Development Outlook 2012: Confronting Rising Inequality in Asia, ADB Manila, p.47. (2012), and OECD (2011), Divided We stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising, Chapter, pp.56-7.

[10] For evidence of this association, see Berg, Ostry and Zettelmeyer (2008), “What Makes Growth Sustained?” IMF Working Paper 08/59, IMF, Washington D.C. Also, Berg, Andrew G. and Ostry, Jonathan D, (2011), “Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin?”, IMF, Washington D.C.

[11] On this issue, see in particular, Joseph E. Stiglitz (2010), Freefall: America, Free Markets and the Sinking of the World Economy, Norton, New York. Also Joseph E. Stiglitz (2012), The Price of Inequality, Allen Lane, London.

[12] See Ravallion, M, and Chen, 2 (2004), China’s (Uneven) Progress Against Poverty, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3408, World Bank, Washington D.C.

[13] As specified in Gill and Kharas (2007)

[14] For a detailed assessment of the combination of this “concentration” with regional disadvantage in the early years of the 21st century, see World Bank (2006) World Development Report: Equity and Development, chapter two, “Inequity with countries: individuals and groups”, World Bank, Washington D.C.

[15] For details of this widening, see OECD (2011), Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising, chapter three, Inequality in Emerging Economies, pp.53-5, OECD, Paris.

[16] For a detailed assessment of the Chinese case, see Li,S, Luo C, (2011), Introduction to Overview: Income Inequality and Poverty in China, 2002-7, CBI Working Paper 2011-10, Department of Economics, University of Western Ontario, Canada

[17] See ADB (2012) Asian Development Outlook 2012: Confronting Rising Inequality in Asia, p.70, Manila, 2012.

[18] Countries selected were China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Bhutan and Thailand. The source for the data was the WB World Development Indicators 2011, table 2.15, Education Gaps by Income and Gender.

[19] See ADB (2012), 16, above, p.65.

[20] See OECD (2011), Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising, OECD, Paris, pp.57-9.

[21] See [21] See ADB (2012), 16, above, p.66.

[22] This rent-seeking can take many forms:- hidden and open government transfers and subsidies, laws making markets less competitive, lax enforcement of laws related to competition, and statutes allowing organisations to pass on their costs.

[23] See ADB (2012), 16, above, p.56.

[24] See Li Xiaoyun, (2010), China: Rural Statistics 2010, China Agricultural Press, Beijing.

[25] See Li Xiaoyun (2012), 24 above.

[26] Data (for 2010) are taken from the World Bank (2012), World Development Indicators 2012, Table 216, pp 100-102.

[27] Source: Lustig, N, et al. (2011), “The Decline in Inequality in Latin America: How Much, Since, When and Why”, Working Paper no.118. Tulane University, Canada, Figure 2.

[28] Figure taken from Lustig, Nora (2011), “Markets, the State and Inclusive Growth in Latin America: Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and Peru”, UNDP.

[29] Data taken from World Bank, World Development Indicators, for each of these years

[30] For example, stock market capitalisation of the seven largest regional economies quadrupled in value, 2004-7. For further information on this trend, see Cornia, Giovanni Andrea (2009), “What explains the recent decline of income inequality in Latin America”, draft paper presented to a Conference on the Impact of the Financial Crisis in India, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, March 2009. , and Ocampo, Jose Antonio (2007), “”The Latin American Boom”, Revista de Ciencia Politica, Volume 28, no.1, pp 7-33.

[31] World Bank (2012), World Development Indicators, Washington D.C, 2012.

[32] For details of the programme and its implementation, see Kostzer, Daniel (2008), Argentina: A Case Study on the Plan Jefes y Jefas de Hogar Desocupados, or the Employment Road to Economic Recovery, UNDP Buenos Aires.

[33] For example, the labour earnings differential between metropolitan areas and small municipalities declined from 26% in 2000 to 19.4% in 2007. See Nora Lustig (2011), “Markets, the State and Inclusive Growth in Latin America: Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and Peru, UNDP, 2011, p.14.

[34] See Lustig, Nora (2011), “Fiscal Policy and Income Redistribution in Latin America: Challenging the Conventional Wisdom”, Society for the Study of Economic Inequality, November, 2011, p.23??

[35] See Cornia, Giovanni, (2009), “What explains the recent decline of income inequality in Latin America?, draft paper presented to a Conference on the Impact of the Financial Crisis in India, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, March 2009.

[36] By way of illustration, during this period, only Ecuador –during 2004-5- had social expenditure/GDP ratio lower than in 1990-1.

[37] See McKinley, Terry (2010), “Inclusive Growth Criteria and Indicators: An Inclusive Growth Index for Diagnosis of Country Progress”, Asian Development Bank, Sustainable Development Working Paper 14, Manila.

[38] See Kanbur, Ravi and Raunyar, Ganesh, (2009), “Conceptualizing Inclusive Development: With Applications to Rurral Infrastructure and development Assistance”, Asian Development Bank, Occasional Paper No.7, Section II, “What is Inclusive Development?”, ADB Manila

[39] See Asian Development Bank (2012), Asian Development Outlook, Manila, p.74.

[40] See for example, evidence presented in World Bank (2009), World Development Report 2009:Reshaping Economic Geography, World Bank, Washington D.C.

[41] See World Bank (2009), World Development Report 2009: Reshaping Economic Geography, World Bank, Washington D.C, pp 88-9.

[42] Most notably, Fan, S., R. Kanbur, and X. Zhang, (2011), “China’s Regional Disparities: Experience and Policy”, Review of Development Finance, 1 (1), pp/47-56. Also, Fan, S., R. Kanbur, and X. Zhang (eds.), (2009), Regional Inequality in China: Trends, Explanations and Policy Responses. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group

[43] Data from Malaysia Economic Planning Unit, 2008, cited in World Bank (2009), World Development Report 2009: Reshaping Economic Geography, Washington D.C., p.27.

[44] See Hill, H, Resosudarmo, B, Vidyattama, Y, (2007), “Indonesia’s Changing Economic Geography”, Working Papers in Economics and Development Studies, 2007-13,Bandung, Indonesia.

[45] See Wisaweisuan, N,(2009) “Spatial Disparities in Thailand: Does Government Policy Aggravate or Alleviate the Problem”, in Reshaping Economic Geography in East Asia ,Yukon Huang and Alessandro Magnoli Bocchi, World Bank, Washington D.C.

[46] Claus, Iris, Martinez-Vazquez, Jorge, Vulovic, Violetta, Government Fiscal Policies and Redistribution in Asian Countries, International Center for Public Policy Working Paper 12-13, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University. Note that the study also shows that whilst expenditure on education in Asia tends to reduce inequality to a relatively greater extent than in the rest of the world, expenditure on health reduces levels of inequality, but less so in Asia than in the rest of the world (see p. 25 of article).

[47] The Di Bao programme is a very basic cash transfer, which does not have a conditionality -beyond the condition of being very poor.

[48] See Ariel Fiszbein and Norbert Schady (2009), Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Present and Future Poverty, World Bank Policy Research Report, Washington D.C.

[49] For evidence on this issue, see Rachel Slater and John Farrington (2009), Cash Transfers: Targeting, ODI Project Briefing, Overseas Development Institute, London,

[50] Data taken from OECD (2011), Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising, OECD, Paris.

[51] For example, In Indonesia (2008) only 34% of eligible workers who lost their jobs received some severance pay, and a majority of this 34% received less than their entitlements. See World Bank (2010), Indonesia Jobs Report: Towards Better Jobs and Security for All, Washington D.C.

[52] See OECD (2011), Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising, p.60, OECD, Paris.

[53] See World Bank (2010), Indonesia Jobs Report: Towards Better Jobs and Security for All, Washington D.C.

[54] These issues are explored in detail in David A. Robalino, Laura Rawlings, Ian Walker (2012), Building Social Protection and Labor Systems: Concepts and Operational Implications, Social Protection and Labor Discussion Paper No.1202, World Bank, Washington D.C. The subsequent discussion draws on some of the conclusions in this Paper.

[55] Data taken from World Bank (2012), China 2030: Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative High Income Society, Washington D.C, p. 372.

[56] Although there is some portability within the urban worker scheme..

扫描下载手机客户端

地址:北京朝阳区太阳宫北街1号 邮编100028 电话:+86-10-84419655 传真:+86-10-84419658(电子地图)

版权所有©中国国际扶贫中心 未经许可不得复制 京ICP备2020039194号-2