Global Poverty Reduction and Development Forum-2012-Chapter III

- The agricultural tax and its reform

- Minimum living standard guarantee

Chapter III: Making a more effective income distribution policy for inclusive development:China’s experiences

LI Shi

Institute for Income Distribution Studies

Beijing Normal University China

I. Introduction

In recent years, the concept of inclusive growth or inclusive development has been universally accepted by academics and policy-makers. The concept was first proposed by the Asian Development Bank, and the launch of inclusive growth strategy to the developing countries in Asia. The Chinese government has accepted this concept, by incorporating it into the 12th Five-Year Plan for economic and social development in China. The effective inclusive growth strategy, according to the Asian Development Bank, implies the need to focus on high growth to create productive jobs and to ensure equal opportunities for all social groups as well as to give the most vulnerable people the social safety net.[1] It shows that inclusive growth has three aspects: first, to promote the high growth with a rise in productive employment; second, to provide equal opportunities for all social groups and development results equally sharing among people; third, to provide social security for the poor and vulnerable groups.

Income distribution policies are varied from one country to another. One of the most important effects of income distribution policies is to narrow income inequalities. Income distribution policies contribute to alleviate poverty and help economic growth. It can be divided into the primary distribution policies and redistributive policies. In terms of the content of the policies, it includes tax policy, transfer payment programs, social security policy and so on. It is clear that to promote inclusive development cannot go without the support of income distribution policies. The income distribution policies to promote inclusive development should have the following basic characteristics.

First, the income distribution policies to promote inclusive development should increase both economic growth and employment. In other words, the income distribution policies should not hinder economic growth, and should be conducive to an increase in employment. For developing countries, giving priority to full employment has gradually become the top target of the economic development. Even if an income distribution policy could help to narrow income inequality, it would not be conducive to employment and does not belong to the income distribution policies to promote inclusive development.

Second, the income distribution policies to promote inclusive development should contribute to the achievement of equal opportunities and social equity. The reason why the poor and low-income population remains in low-income status is mainly because they lack of social rights and equal opportunities. Therefore, to improve the basic rights, and to create more opportunities in income-generating ability for these population groups, will become the important features of the income distribution policies from the perspective of inclusive development.

Finally, from the view of the broader concept of income, personal income or family income not only includes disposable income, but also includes the market value of the public services enjoyed. Social security and welfare system constitute the main content of the public services. Therefore, the basic social security for all members of society, especially vulnerable groups, to obviate the risk of their participation in the competition in the market, will also be an important feature of the income distribution policies for inclusive development.

China has achieved rapid economic growth over the past 30 years, greatly reducing the urban and rural population in absolute poverty. However, due to the continuous expansion of the income gap between urban and rural areas and regional development imbalance, the relative poverty has become increasingly prominent. For China, with economic development and the improvement of residents' income levels, the understanding of poverty will change accordingly, from a focus on absolute poverty to the emphasis on relative poverty. Some relevant changes in poverty reduction strategy indicate that poverty alleviation in a country is to solve the problem of food and clothing for those living in absolute poverty in the stage of low-income levels. However, poverty alleviation should tackle the problems of development capability of the relatively poor as a country moves into the ranks of middle-and high-income countries. China has become a middle-income country and is also facing the transformation of her poverty reduction strategy.

This report will describe the existing income distribution policies in China. In particular, it focuses on the policies that help promote inclusive development and also proposes the future policy adjustments. This report is divided into the following sections. In Section II, it discusses the concept of inclusive development and its relationship with income distribution, how inclusive development to be judged from the perspective of income distribution. The absolute standards and relative standard of inclusive development are proposed. Section III discusses the income distribution and poverty issues facing China, especially relative poverty. Section IV evaluates existing income distribution policies, especially from the perspective of inclusive development. Section V provides some policy recommendations.

II. Inclusive development and income inequality: the concept discussion

In the past three decades, China's economic growth rate was staggering. Particularly in the past ten years, the GDP growth rate was above 10% annually. With the rapid economic growth, the poverty in urban and rural areas has been significantly eased, but the income inequalities have expanded. In this situation, from the inclusive development point of view, how should we judge China's development model? From the perspective of the income inequality, it is not all social groups benefiting from economic growth equally. However, from the point of view of poverty reduction it is an inclusive development mode. Obviously, there are differences in the understanding of the concept of inclusive development. A key problem is that inclusive development model requires that all members of society share equally the fruits of economic development? Does it allow the different members of society enjoy different development outcomes?

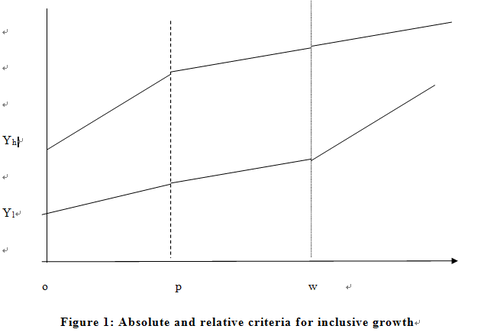

In order to address this issue, it is necessary to distinguish between two kinds of absolute standard of inclusive development stage standard. The former refers to every member of society can enjoy the economic and social development achievements, but allows different members to receive different outcome. The latter refers to all members of society should enjoy the same economic and social development outcome and there should not be a difference in the distribution of the outcome. From the point of view of income inequality, the absolute standard of inclusive development model allows the inequality widening, or maintaining the inequality constant while the relative standard requires narrowing the income inequality. Regarding the absolute standard, if it is the high-income people benefiting more than low-income people, the income gap is still widening, which is only a low absolute standard. In another case, the high-income and low-income people to share the outcome equally, then it is high absolute standard. Distinction of the three standards is shown in Figure 1. The Yh line represents income growth for high-income people, Yl for low-income growth. At OP stage, both high-income and low-income population has income growth, but the income growth of the former is faster than the latter, the income gap is rising. This stage is low absolute standard of inclusive development stage. At the PW stage in which both high income and low-income population have synchronous income growth, the income gap will not expand. Thus it is a high absolute standard of inclusive development stage.

Which standards should be adopted for inclusive development model largely depends on the initial conditions of the income inequality in a country. If a country has a modest inequality, such as income inequality at the beginning of China's reform, expanding income gap promoting efficiency, it became a necessary means to adopt a low absolute standard inclusive development model. If the initial conditions of a country are the opposite, the income gap is large, the low absolute standard of inclusive development model becomes undesirable, and the relative standard of inclusive development model is a necessary choice, at least high-absolute-standard inclusive development model should be chosen. The Chinese government understands the difficulty of choosing a relatively standard inclusive development model, therefore adheres to the high-absolute-standard inclusive development model.[2]

III. Changes in income distribution and poverty in China

Since the reform was launched in the late 1970s, China's income distribution system has undergone substantial changes, and the pattern of income distribution has greatly changed. The country has moved from an egalitarian society into highly unequal one. Some suggest that China has become one of the countries with highly unequal income distribution in the world. To make a judgment on the mode of economic development of China over the past 30 years, it is necessary to describe and explain its main features of the income inequality. Several important characteristics for changes in the distribution of income among the Chinese in the last three decades are summarized as follows.

Feature 1: All-round expansion of the income gap. To illustrate this feature, it is reflected through the changes in income inequality within urban areas, within rural areas and in the country as a whole.

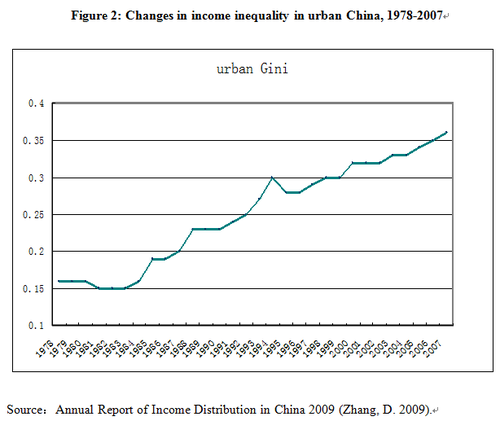

Regarding income distribution within the urban areas in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Gini coefficient was estimated about 0.23. The income inequality was wider compared to the inequality at early stage of the reform, but at a low level.[3] The Gini coefficient of the income distribution among urban residents has reached 0.33 in 2002 (Li and Yue, 2004). Meanwhile, the income gap between high-income groups and low-income groups tended to further expand. The income share of the richest 5% of the population in the urban areas is 15% in 2002, the share of the richest 10% of the population is 28%. By contrast, the income share of the poorest 5% of the population is only 1.2%, and the share of the poorest 10% of the population is only 3%. It is not difficult to calculate the income ratio of the richest 5% to the poorest 5% in the urban areas. It is nearly 13:1. The ratio for the richest 10% to the poorest 10% is nearly 10:1 (Li and Yue, 2004). The latest data show that the Gini coefficient within urban China has risen to 0.36 (see Figure 2). Therefore, the income grwoth of the low-income people was slower than the high-income people in the past three decades, with income gap widening, so it is the low-absolute-standard inclusive development at this stage.

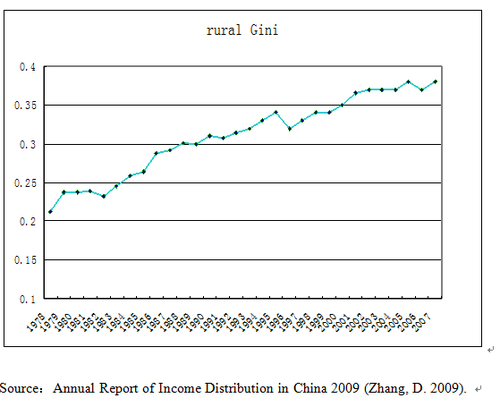

The Gini coefficient of rural income inequality is estimated to be 0.38 (see Figure 3). Regarding changes in rural income gap, although the findings leading to different conclusions, but there are two points that we agree with.

First, the existing rural income gap is much larger than it was at the beginning of economic reform. Some relevant studies have shown that, for the distribution of income of rural residents, the Gini coefficient is about 0.22 in 1978 (Li Shi, 1997). In other words, in 30 years of the process of economic transition and development process, the rural income inequality has widening by 68 percent.

Second, rural China experienced two periods "fast and slow" in the expansion of income inequality in the period 1997-2007. According to estimates of the National Bureau of Statistics, the rural Gini coefficient rose from 0.32 in 1997 to 0.37 in 2002, an increase by 5 percent. It is the faster period for widening income gap. In rural areas in 2002, the richest 5% of the population account for a total revenue share is 18%, and the possession of the share of the richest 10% of the population is 28%, while the crowd occupies a total income of the poorest 5% share of only 1%, the most the poor the share of 10% of the population, but is 2.5%. The average income of the richest 5% of the population is the poorest 5% of the population of nearly 18 times the average income of the richest 10% of the population is more than 11 times that of the poorest 10% of the population (Li Shi and Yue Ximing, 2004). Rural income disparities very slow period from 2002-2007, the past five years, the Gini coefficient rose by only 1% (see Figure 3).

As for the national income gap and its changes, the National Bureau of Statistics rarely calculated Gini coefficient for China as a whole, so this discussion can only be based on the estimated results of the research projects.

According to the estimates by the World Bank, in the early 1980s, the national Gini coefficient is about 0.31 (Ravallion and Chen, 2004). At the end of the 1980s, according to the data from the first wave of the China Household Income Project surveys (CHIPs), which includes in-kind income of urban household income and housing subsidies, as well as imputed rent privately owned housing into the personal disposable income, the estimated national Gini coefficient is 0.382 (Griffin and Zhao, 1993). The income share of the 10% highest income group in 1988 was 7.3 times higher than the lowest income group (Khan et al, 1992). The findings of the research project indicate that the country's Gini coefficient reached close to 0.46 in 2002. The income share of the 10% top group is nearly 32% of the total income; the figure for the 10%lowest group is 1.7%. Obviously, the average income of the highest group is 19 times of the 10% lowest group (Li and Yue 2004). The Gini coefficient of national income inequality in 2007 is estimated about 0.49, and the average income of the highest group is 23 times of the 10% lowest group (Li et al, 2010).

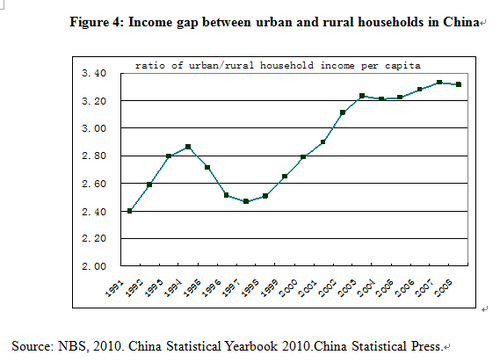

Feature 2: The income gap between urban and rural areas is particularly prominent. The income ratio between urban and rural residents reflects changes in the relative income gap. Since 1990, the ratio experienced a rise - fall - rise process (see Figure 4). The income gap between urban and rural areas in the 1990-1994 period is widening, with the income ratio rose from 2.2 times in 1990 to 2.6 times in 1994. Therefore, the income gap between urban and rural narrow was narrowing, a process that lasted just three years, in which the income ratio decreased from 2.6 times in 1994 to 2.2 times in 1997, and that is down to 1990 levels.

However, since 1998, the income ratio between urban and rural areas has been rising up, from 2.2 times in 1997 to 2.5 times in 2000, and a further rise to 3.23 times in 2003. In recent years, the income gap between urban and rural areas is basically fluctuated up and down at high level. Based on the household survey data of the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2009, the income ratio between urban and rural areas reached to 3.3:1, to 3.2:1 in 2010 and to 3.1:1 in 2011.

It is worth mentioning that the nationwide personal income inequality is broken down into three parts, within the urban areas, within rural areas and between urban and rural areas. The income gap between urban and rural areas in the period 1995 - 2002 as a percentage of the national income gap increased from 38% to 43%, an increase by five percent (Li and Yue 2004). This means that more than two fifths of the National income gap is explained by the income gap between urban and rural areas in 2002. This also means that the rapid expansion of the income gap between urban and rural areas constitute one of the main driving factors of the national income disparities. The decomposition results (using the 2007 data) indicate that the contribution of the income gap between urban and rural areas to the national income gap rose to about 48% (Li et al, 2010).

Feature 3: The income disparities across regions are still relatively large. Over the past years, China has a significant income gap between regions. The regional income disparities are too large both from historical reasons, and as the subsequent emergence of new problems. It is partly because there is a huge gap between the urban and rural, regional disparities are caused by differences in the structure of the regional differences in the urban and rural population, in part caused by the regional income gap within rural and urban areas. The regional income gap within rural areas, even at the beginning of reform and opening up, was quite obvious. In the last century, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, due to the process of rural industrialization, there was greater regional imbalance in rural residents' income growth across provinces.

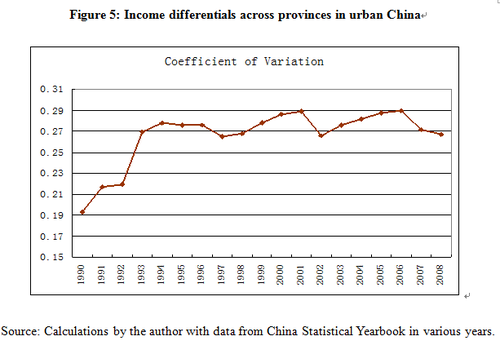

However, in the late 1990s, stagnation in agricultural production, recession in production of township enterprises, there was no obvious widening regional gap within the rural areas. However, the changes in regional disparities within urban areas represent the urban household income gap is expanding across provinces. Shown in Figure 5, in the 1990 - 2003 period, measured by the coefficient of variation between provinces, urban per capita disposable income difference is expanding, especially in the early 1990s. It has been particularly evident in the coefficient of variation rising from 0.192 in 1990 to 0.278 in 1994. From the mid-1990s, the coefficient of variation of the per capita income of urban areas across provinces fluctuated between 0.27-0.29. This means that the regional income differences between provinces was widening with a slowdown speed, but it does not appear to have a narrowing trend.

Despite China's widening income gap, it does not appear a case of polarization. The widening income gap was mainly due to the fact that income growth of high income groups was faster than that of low-income groups. Moreover, the poor population dropped significantly in the last three decades. In this sense, China's development pattern is a low-absolute-standard inclusive development model.

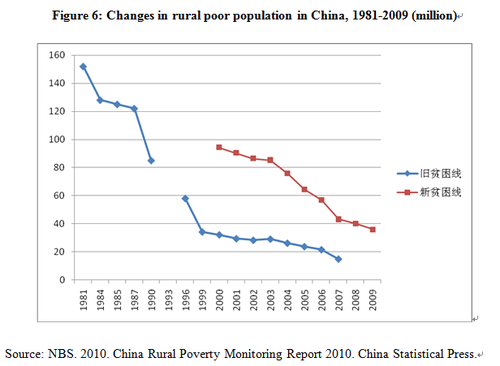

Looking at the poor population changes in rural China, it is also clear that the income of the poor and low-income people is in a growing trend. Figure 6indicatesthe number of the rural poor in China since the 1980s. Obviously, the number of the poor is in a declining trend, whether it is based on the lower poverty line or upper poverty line. Based on the lower poverty line, the rural poor decreased from 150 million in the early 1980s to 16 million in 2007. Based on the upper poverty line, the rural poor decreased from nearly 100 million to less than 40 million in the past decade.[4]

The Chinese government raised the rural poverty line from 1360 yuan / year / person to 2,300 yuan / year / person in 2011, in order to assume more responsibility for poverty reduction. Under the new poverty line, the number will increase to 130 million rural poor. To some extent, the government's anti-poverty policies will benefit more the rural population.

IV. Income distribution policies in China: evaluation from the angle of inclusive development

The policy tools for income redistribution in the era of the planned economy that the Chinese government was enable to use were very limited. However the measures to narrow the income gap were more institutional arrangements, such as canceling the private economy, and strictly control on the wage distribution system in public enterprises, and widely adopting collective distribution system in the people's commune system in rural areas. With low levels of per capita income and small income gap, the income distribution policy became useless. In the past thirty years, the Chinese government introduced a number of income distribution policies.

In the planned economy period, although the income of urban residents was higher than that of rural residents.[5] The former were not subject to personal income tax, while the latter were required to pay agricultural tax and other taxes. The taxes paid by farmers included agricultural tax, special agricultural product tax, slaughter tax and deed tax, known as "Four Agricultural Taxes".

In addition, farmers had to pay a variety of other taxes and those required by government were summed up as "Three Retained Fees and Five Overall Planned Fees". In many places, the amount of these fees was much higher than the agricultural tax. In addition, farmers were required to pay other fees in all kinds of names, especially in the 1990s; the tax burden on Chinese farmers reached a high level, resulting in public resentment and complaints. Facing over-taxation of some local governments, the central government had issued repeated orders and various documents to curb the behavior of local governments. However, as the central and local governments did not make a fundamental adjustment of the financial relationship between the central government and local governments, the binding provisions did not fundamentally solve the problem.

Table 1:Average tax (fee) rate on different income groups from 1988 to 2007 (rural China)

|

Decile income groups |

1988 |

1995 |

2002 |

2007 |

|

Lowest 10% |

7.5 |

13.9 |

6.2 |

0.3 |

|

Lowest 20% |

6.5 |

12.0 |

5.4 |

0.3 |

|

Highest 20% |

4.1 |

3.4 |

1.7 |

0.3 |

|

Highest 10% |

3.8 |

3.0 |

1.5 |

0.4 |

|

Average |

5.0 |

5.3 |

2.8 |

0.3 |

Source: Calculation based on 1988, 1995, 2002 and 2007 CHIP data.

In accordance with the provisions of the central government, the amount of the all taxes and fees must not exceed 5% of the net income of local farmers in the previous year. Some survey data suggest that this amount was much higher than the standard in many places. The research group of "County Finance and Income Growth of Farmers" of the Development Research Center of the State Council carried out a special investigation into farmers’ burden recently in three agricultural counties and found that the tax rate on the farmers in these three counties in 1997 was 12%, and this ratio even reached 28% in one county where rural residents had the heaviest tax burden.[6]

Facing the growing burden of farmers, the central government finally made a determined effort to fundamentally solve the problem. Therefore, from 2006 the government exempted the agricultural tax nationwide and no longer allowed local government to collect the so-called "Three Retained Fees and Five Overall Planned Fees". As the 2007 household survey data shows, the tax burden on farmers has become negligible.

Table 1 shows the changes in tax burden on rural households in the two decades from 1988 to 2007. The average tax burden in 1988 was 5% and reached 5.3% in 1995. In 2000, pilot reform on agricultural tax was launched and the tax burden in some places began to decline, and dropped to 2.8% in 2002. Since 2006, when agricultural tax was exempted nationwide, the average tax burden on farmers dropped to 0.3% in 2007. Such a process of change reflects the general situation of water rate burden of farmers during this period.

Table 1 also shows the tax burdens of rural high-income and low-income households. These results are more interesting. It is obvious that in 1988, 1995 and 2002, the average tax (rate) burden on low-income households was significantly more (higher) than that of high-income households. The tax rate on the lowest-income households (10% of the total) nearly doubled that on the highest-income households (10% of the total) in 1988 and, in 1995, the former was four times the latter. Although the average household tax (fee) rate decreased in 2002, the difference between the tax (fee) rates of low-income group and high-income group did not fundamentally change.

From the perspective of income distribution, rural tax policy has a strong regressive effect. It is not conducive to narrowing the income gap. Instead, it leads to a growing income gap. On the one hand, it expands the income gap within rural areas. The relevant results show that, the Gini coefficient of income inequality after tax is higher than the Gini coefficient before tax, which was particularly evident in 1995. This indicates that the tax has led to the expansion of rural income gap. On the other, it expands the income gap between urban and rural residents. In 1995, for example, the income gap between urban and rural residents was 2.47 times. If agricultural tax would have been exempted, the income gap between urban and rural residents would have dropped to 2.34 times.[7]

From the perspective of inclusive development, China implemented the rural taxes with a strong intention to increase government revenue. It did not realize that it would widen income gaps and aggravating the rural poverty, and thus it is against the basic principles of the inclusive development model. By contrast, the Chinese government waived the rural tax and fee policy, which conforms to the requirements of inclusive development to some extent.

2. Personal income tax policy

In the 1980s, the Chinese government introduced personal income tax policy. However, as the required threshold was much higher than the income level of average urban residents, only a small proportion of the population had income reached the threshold, the personal income tax did not play a role in regulating the distribution of income. Later, with the rapid growth of urban residents’ income, coupled with no timely adjustments to the threshold, more and more people need to pay personal income tax. As a result, the growth rate of personal income tax is higher than that of urban residents’ income, reached 483.7 billion yuan in 2011, a real increase by 9.4 times compared with that in 1999.

The growing personal income tax actually does not play a significant role in adjusting the income distribution of urban residents. The main reason is that China’s personal income tax is the single-item tax (a tax on each income) rather than integrated tax (tax collection based on family income and the population).

Another reason is that some high-income groups have a variety of methods of tax evasion. However, the proportion of personal income tax in the government revenue is not high. For example, in 2010 it accounted for only 6.6% of total government revenue while a large part of the government revenue comes from indirect taxes such as value added tax, consumption tax and business tax.

In order to make further analysis on the income distribution effect of personal income tax and make clear how it helps narrow the income gap instead of expanding the gap, we used the data of 12700 households participating in the survey of National Bureau of Statistics of China on urban residents in 2008 to calculate the income taxes paid by urban residents and the tax rate (tax/income) and found that both the amount of the personal income taxes paid by urban residents and the tax rate were relatively low. In 2008, the average personal income tax paid by urban residents was 268 Yuan per person, and the average tax rate was less than 1%.[8] Meanwhile, the personal income tax and tax rate for each decile group can also be calculated, shown in Table 2. It is obvious that tax rate is certainly progressive. The tax rate of high-income groups is higher than that of low-income groups. This means that at least by 2008, urban personal income tax played a positive role in reducing income inequality, although its role was limited. For example, before tax collection, the income per capita of the highest-income group is 9.48 times that of the lowest-income group. However, it dropped by 9.29 times after the tax collection.

Table 2: Personal income tax burden on urban residents in decile groups in 2008

|

Income decile group |

1 (Lowest) |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Per capita income (Yuan) |

5427.4 |

8423.9 |

10665.9 |

12711.6 |

14830.6 |

|

Per capita tax (Yuan) |

0.2 |

1.8 |

5.8 |

8.7 |

18.2 |

|

Tax rate(%) |

0.004 |

0.022 |

0.054 |

0.069 |

0.123 |

|

Income decile group |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10(Highest) |

|

Per capita income (Yuan) |

17265.8 |

20276.5 |

24258.0 |

30534.6 |

51466.6 |

|

Per capita tax (Yuan) |

29.5 |

60.7 |

117.1 |

251.9 |

1059.2 |

|

Tax rate(%) |

0.171 |

0.299 |

0.483 |

0.825 |

2.058 |

Source: calculation based on 2008 CHIP data

Transfer payments to low-income people in the Chinese government welfare programs is very limited, one of which is Minimum Income Guarantee System (MIGS, Dibao) implemented in the past decade. The system was first introduced in the city, and later extended to the rural areas. At the end of 2010, 23.1 million of urban residents and 52.1 million of rural residents were supported by MIGS (Table 3). The annual expenditure of the government on urban subsistence allowances was 52.47 billion Yuan, 8.8% up over the previous year, of which 36.56 billion Yuan was central government subsidies, accounting for 69.7% of the total expenditure in 2010. People who received the subsistence allowances are mainly unemployed persons, elderly without pensions and minors. These three kinds of people accounted for more than 70% of people receiving subsistence allowances.[9] In 2010, the average urban subsistence allowance standard nationwide was 251.2 Yuan per person, up 10.3% over the previous year; and the monthly subsistence allowances received by urban residents was 189.0 Yuan per person, up 9.9% over the previous year.

Although urban minimum income guarantee system does not have a significant impact on the income gap, it has an obvious effect on poverty alleviation. If the local minimum income standard is taken as the poverty line, then, based on CHIP 2007 urban household survey data, we can work out the changes in poverty incidence, poverty gap and weighted poverty gap before and after the subsistence allowances. The results show that, the poverty incidence declined by 42% as a whole. More importantly, the decrease rate of the poverty gap and weighted poverty gap was even higher, respectively reaching 57% and 63% (Li and Yang, 2009). This means that the subsistence allowance has not only lifted a considerable number of people out of poverty, but also made their income above the poverty line. Even to those who have not shaken off poverty, the living standards have been improved and the poverty has been alleviated.

Thus, the urban minimum income guarantee system it not only a government income transfer policy, but also a policy for re-distribution of income. Its impact on income distribution, in terms of narrowing income gap, is very limited. However, in terms of poverty alleviation, its impact is significant. Clearly, it is an effective pro-poor income distribution policy.

Compared to the urban minimum income guarantee system, the rural minimum income guarantee system was established a few years later and was not promoted in all rural areas until 2007. Compared to 2007, for example, more than 46% of the rural residents received the subsistence allowance in 2010. There was an increase of 67% in per capita subsistence allowances. The increase in real terms was more than 55%. Moreover, the per capita subsistence allowance income of the secured households also almost doubled.

Table 3: Changes in rural minimum income guarantee system

|

|

Provinces covered

|

Targets(10,000 households) |

Targets(10,000 people) |

Coverage(%) |

Per capita subsistence allowance (Yuan / month) |

Per capita allowance gap (Yuan / month) |

|

2004 |

8 |

236 |

488 |

0.64 |

- |

- |

|

2005 |

13 |

406 |

825 |

1.11 |

- |

- |

|

2006 |

23 |

772 |

1593 |

2.16 |

- |

35 |

|

2007 |

31 |

1609 |

3566 |

4.90 |

70 |

39 |

|

2008 |

31 |

1982 |

4306 |

5.97 |

82 |

50 |

|

2009 |

31 |

2292 |

4760 |

6.61 |

101 |

68 |

|

2010 |

31 |

2529 |

5214 |

7.24 |

117 |

74 |

Source: Civil Affairs Development Statistics Report

The rapid expansion of the coverage of rural subsistence allowances, but due to the low level of protection for narrowing the rural income gap is very limited. Urban low-income redistribution effect is identical. It was, then, what should be done to alleviate rural poverty? Table 8 Rural Poverty Monitoring Survey 2008 data obtained the FGT index changes before and after in the guaranteeing income, guaranteeing that crowd and guaranteeing crowd can be seen from the role of guaranteeing that income to alleviate poverty. The data show that the data of the 2008 pro-poor focus counties 3835 low households, 16,636 individuals for a minimum target. Poverty Countries guaranteeing that coverage is 7.28%, higher than the national rural average. Are shown in Table 8, for guaranteeing that the crowd, when the poverty line of 1,196 yuan (official new adjusted poverty line), guaranteeing income makes this group the incidence of poverty fell by 21%, the poverty gap declined by 32.6%, weighted poverty gap declined by 37.5%. This means guaranteeing policy makes more than two percent of the crowd enjoy the minimal out of poverty the poverty populations out of poverty, but also makes more obvious improvement.

4.Pro-farmer policies

Since the beginning of the new century, in order to better implement the strategy of balanced development, the Chinese government implemented a series of pro-farmer policies. Based on the ways to benefit farmers, the government's pro-farmer policies can be divided into two categories. First, subsidy policies aimed to directly increase farmers’ income, including direct subsidies to grain, improved varieties subsidy, farm machinery purchase subsidy, etc. Second, public service policies aim to establish farmers’ social security network, mainly including new cooperative medical system, "two exemptions and one subsidy" policy for education, rural minimum income guarantee policy, etc. Clearly, these pro-farmer policies played a certain role in increasing farmers’ income and reducing the income gap between urban and rural areas.

More importantly, these policies played a positive role in narrowing the income gap within rural areas and alleviating rural poverty. For a long time, agricultural prices in China are generally low, coupled with the decentralization of land management and low scale of production, agricultural yield is low, and so the income of farmers from agricultural production is very limited. It means that the farmers engaged in agricultural production, especially grain production are low-income or poverty-stricken people.

Some research shows that farmers get income from agriculture, which has an equalizing effect on of the income gap in rural areas to some extent (Khan and Riskin, 1998). Thus, subsidies to agriculture, including grain subsidies and price subsidies for agricultural production, would benefit those households, which are engaged in agricultural production. It would also make their income increase at a higher speed, narrow the income gap within rural areas and reduce their risk of falling into poverty.

In addition, the compensation policy for reforestation is issued in 1999. The pilot projects of reforestation were first constructed in Shaanxi, Gansu and Sichuan province. In 2000, the project implementation areas expanded to the upper reaches of Yangtze River in the west such as Yunnan, Sichuan, Guizhou, Chongqing and Hubei, and 174 counties of 13 provinces in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River, including Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Henan and Xinjiang. In 2002, the project of reforestation was implemented comprehensively across China and the coverage extended from west-based 20 provinces (autonomous regions) to 1897 counties in 25 provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities) nationwide. With the gradual increase in the compensation standards, this policy has been widely welcomed by local farmers.

In terms of geographical distribution of the project, most of benefited farmers live in the mountainous and ethnic minority areas with income levels far below the national average. The compensation policy for reforestation has increased their income to some extent. It helps narrow the income gap within rural areas and between regions. Meanwhile, these people live in the areas with high incidence of poverty. The direct subsidies from the project will help to alleviate the poverty of these regions and increase opportunities for them to create income. People at the edge of poverty usually have a strong sense of risk aversion, combined with their low income, they lack the ability to take a risk or liquidity costs and is often reluctant to work outside. For the poor, the subsidy from the projects to a certain degree will increase their intention and opportunities of working outside the home or engaging in non-agricultural industries, thus promoting the poverty alleviation in these project areas.

It should be noted that these pro-farmer policies are reflected in the farmers’ income composition to some extent. As table 4 shows, in the period from 2005 to 2008, the proportion of transfer income in the net income of rural households in the poverty-stricken countries grew by 50%, and the growth rate of the poor households was even higher, exceeding 66%. In addition, the proportion of transfer income in the net income of poor households is actually higher than that of the non-poor. For example, in 2008, the former was 30% higher than the latter. The main factors to promote the rapid growth of rural households’ transfer income are the government’s pro-farmer policies, especially those subsidies and reliefs in cash, such as grain subsidies and subsistence allowance.

Table 4:Proportion of transfer income in the net income of rural households in poverty-stricken counties from 2005 to 2008

|

Year |

Proportion of transfer income in the net income(%) |

||

|

All samples |

Sample of poor households |

Sample of low-income households |

|

|

2005 |

4.5 |

6.0 |

4.9 |

|

2006 |

5.0 |

9.4 |

6.1 |

|

2007 |

5.4 |

9.4 |

7.4 |

|

2008 |

6.8 |

10.1 |

|

Source: NBS, China Rural Poverty Monitoring Report.

5. Social security system

In the past ten years, China experienced social security system reform and one of the objectives of the reform is to establish a social security system covering all Chinese. Social security system is expanded towards the urban informal sector and migrant workers. The income distribution and poverty reduction effects of China's social security system reform are also worth mentioning, but there are some difficulties in the research. This is because social security is part of public policy and is, to a great extent, only reflected in the government or personal expenses rather than individual residents or family income. The basic indicator used in both research of the distribution of income and the measurement of poverty is income. For example, people with health insurance will save personal medical expenses, but this does not affect their income. If income is taken as an indicator to measure poverty, it will not affect their poverty status no matter whether people have participated in medical insurance.

For China, the good momentum of social security in rural areas is worth mentioning. So far the new rural cooperative medical system has basically covered all the rural population. By the end of 2008, it had covered all the counties (municipalities and autonomous regions) with rural population and a total of 815 million farmers had participated in the system, accounting for 91.5% of the total rural population. A total of 1.5 billion people nationwide have received the compensation and the compensation fund expenses amounted to 125.3 billion Yuan.[10]

In addition, in recent two years, the government continued to raise the proportion of government investment funds and the proportion of reimbursement of medical expenses, making the actual benefits of farmers continue to increase. It is of great significance to rural poverty alleviation, especially the poverty caused by diseases. The pro-poor effect of the pilot projects of new rural endowment insurance system implemented in 2010 has not been explored so far. After it is widely promoted in rural areas across the country in four years, it will play an important role in reducing poverty, especially the poverty of rural elderly. Because these social security projects are supported by government funds, they can be called the government's income redistribution policies to a large extent. Combined with its characteristics of anti-poverty, they can also be called the income distribution policies conducive to poverty reduction.

V. Making the income distribution policies more conducive to inclusive development

From the perspective of inclusive development, there are many improvements and adjustments in China's income distribution and redistribution policies. It is mainly reflected in two aspects. First, the policy system needs to be completed. Second, it requires close coordination between the various policies. Based on the different standards of our concept of inclusive development, China's economic and social development in the past 30 years can be viewed as an inclusive development model, but that is in the low absolute standard. In the long run, this pattern of development is not sustainable, because it can not guarantee all people of the society to share the fruits of economic development equally. In addition, the large income gap will lead to an imbalance of economic development and social instability. Thus, China's economic and social development needs a transition from a low-absolute-standard inclusive development model to a high-absolute-standard inclusive development model, and the income distribution policy needs to promote the transition.

Income distribution policy can be divided into two types-direct policies and indirect policies. The so-called direct policy is that the policy itself has direct effects on income of different income groups to make the income inequality changed. For instance, personal income tax is one of the direct policies. If a direct income distribution policy leads to a narrowing income gap, then the policy is progressive; if it leads to a widening income gap, it is regressive. The agriculture tax in China is such an example. An indirect policy aims at changing opportunities of different population groups in making income, to lead to changes in the pattern of income distribution, such as employment policies contributing to the achievement of the goal of full employment, and has a role to narrow the income gap. The employment policy can be termed as an indirect income distribution policy.

Based on the above considerations, we propose the following income distribution policies, with particular emphasis on its role to promote inclusive development of Chinese society.

First, China should achieve full employment as one of the most important income distribution policies. To achieve the full employment is also one of the main objectives of inclusive development model.

Second, in order to enhance its anti-poverty function and the function of distribution and redistribution of income, China’s tax revenue system should be adjusted in two aspects. On the one hand, indirect taxes should be decreased and direct taxes should be increased gradually. The tax theory suggests that indirect taxes are for all with the same tax rate for different income groups. In other words, people who spend more pay more taxes, including the poor, need to undertake the same tax rate with the rich. Direct tax, however, is based on personal income and business income, and progressive tax rate scan be determined based on the income level, hence strengthening its role of reducing income inequality. Reduction of indirect taxes may help enhance the wage level. It also leads to a rapid growth of wages of the poor. On the other hand, the government should change the personal income tax from the current itemized tax to general tax. The former is the taxation on each income while the latter is general tax on family income. The implementation of general tax can avoid the embarrassment of tax payment of low-income groups and the poor and might enhance the function of narrowing income gap of personal income tax.

Third, China's income distribution policy does not involve a large number of government transfer payment projects. The existing transfer payment projects such as urban and rural minimum income guarantee systems and social relief projects are at a low level of security. The government should classify different vulnerable groups, especially the vulnerable people without the ability to work, and develop related transfer payment projects based on the characteristics of various vulnerable groups. Apart from a minimum income guarantee for low-income people, the government should also need to develop targeted transfer payment projects for the disabled, orphans, AIDS patients, children and the elderly from low-income families, single parent families and other vulnerable groups. The experience of some countries shows that child allowance is an effective way to alleviate child poverty and prevent child malnutrition. For China, the implementation of a nationwide system of child allowances is unrealistic, but it does not mean that we must implement this policy in rural areas or rural poor regions. Rather, the government should implement the child allowance to urban low-income families. Similarly, the old age subsidy is also an option of income transfer payment policy. China's long-established social pension insurance is linked with formal sector employment, which means that a large portion of the population is not covered by social pension insurance, including the elderly in rural areas, urban elderly without employment experience and the retired people from the informal sector. Old age subsidy is necessary for the elderly and can help to alleviate their poverty, as they are usually the most vulnerable group of people to poverty.

Fourth, complete coverage of the social security system and the equalization of public services not only help regulate the distribution of income, but also help alleviate poverty. The reform should be kept going. In the reform process, the government should make sure that the poor enjoy social security benefits. As for the new rural cooperative medical system (NCMS), the government has increased investment in new rural cooperative medical system in recent years. However, farmers’ reimbursement rate is merely around 50 percent, which is even lower than many other regions. For some low-income families, the proportion of person burden in the medical costs is extremely high. As a result, some poor people do not see a doctor when they are ill. In this case, different reimbursement rates for different income groups can be determined. The lower the income of farmers is, the higher reimbursement rate they enjoy. In this way, it will make the new rural cooperative medical system have a better pro-poor effect. The pension subsidy policy implemented in some places also has the same problem. In issuing pension subsidy, the income status of families is not taken into account and the same standard is used. Therefore, regarding the future development of the elderly’s subsidy policy, the Chinse government should consider the income level of the family of the elderly and develop different subsidy standards to make the pension subsidy have a better pro-poor effect.

Fifth, the implementation of China's pro-farmer policy will continue, as it has played a positive role in narrowing the income gap between urban and rural areas and alleviating rural poverty. Meanwhile, in the implementation process, the policy will be continuously improved. One important improvement measure is to enhance its poverty reduction role. So far grain subsidies has used the relatively uniform national standard for both developed areas and poverty-stricken regions. It is not necessary to use different standards. The government can enhance the grain subsidy standard for backward areas; especially impoverished areas to make the farmers engaged in agricultural production and low-income farmers gain more benefits. It is possible to develop different food subsidies for different regions and different income groups, which could not bring predictable side effect. In addition, the significance of this policy in reducing poverty will be emphasized. Regarding other agricultural subsidies, we should develop different subsidy standards.

Sixth, while striving to achieve the goal of equalization of public services, the government should give more compensation to poverty-stricken areas and the poor. The equalization of the public services has positive policy implications. It attempts to correct the discriminatory public services policies that have long been practiced. However, as these discriminatory policies have resulted in a long-term effect, some discriminated people such as farmers and rural migrants lag far behind the national average in human capital accumulation and wealth accumulation. Even if we achieved the goal of equalization of public services, in a short period of time, it is difficult for these people to catch up with those who have long been enjoying the public service benefits, so it is more possible for them to fall into poverty than other groups. Thus, at the early stage of the policy changing, public service supply should be given the priority to these people. Only in this way, can we eliminate the differences in development opportunities for different groups and lift the vulnerable people out of poverty in the near future.

In this regard, one of the most prominent examples is the development of basic education in backward areas. Although the nine-year compulsory education is basically universally implemented in rural areas nowadays, the quality of education is worrying. If the government cannot fundamentally solve the problem of low quality of compulsory education in rural areas, the poverty in China will continue to exist and poverty will “transfer” from rural areas to the city with the movement of rural population. To improve the quality of compulsory education in rural areas and narrow its differences with the quality of urban education, support from the government especially a large amount of government investment is needed. Meanwhile, high-quality educational resources need to be transferred to rural areas and poverty-stricken areas.

In conclusion, from the perspective of inclusive development, there are many works to do for China to reform the income distribution system. China has adopted an inclusive development model, supported by income distribution policy which can bring a higher rate of economic growth, equal employment opportunities, a more equitable sharing public resources mechanism, more harmonious and stable social environment.

References

ADB, 2007.“Inclusive Growth toward a Prosperous Asia: Policy Implications”, Working paper series.

Chen Xiwen ed. (2003), "Research on China's County Finance and Income Growth of Farmers", Taiyuan, Shanxi Economic Press.

Deng Quheng, Li Shi (2010), "Assessment of the rural social security progress and its poverty reduction effect: based on the case of the minimum living security system", a background report prepared for the Evaluation Report of the Implementation Effect of "China's Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development Outline (2001-2010)".

National Bureau of Statistics (2009), "China Rural Poverty Monitoring Report 2009", China Statistics Press.

Gustafsson, Bjorn, Li Shi, Terry Sicular (2008) Income Inequality and Public Policy in China, Cambridge University Press, April 2008.

Khan, Aziz and Carl Riskin (1998) "Income and Inequality in China: Composition, Distribution and Growth of Household Income, 1988 to 1995", China Quarterly, 154, June 1998.

Li Shi ed (2010), Evaluation Report of the Implementation Effect of "China's Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development Outline (2001-2010) ".

Li Shi, LuoChuliang (2007), "A Reassessment of China's Urban-rural Income Gap", "Journal of Peking University", 2007, No. 2.

Li, Shi, LuoChuliang, Terry Sicular. “Changes in income inequality in China,2002-2007”. Paper presented in the Workshop of Income Inequality in China, Beijing, May 21-22, 2010.

Li Shi, Hiroshi Sato and Terry Sicular (2013).Rising Inequality in China: Challenge to a Harmonious Society. Cambridge University Press.

Li Shi, Yang Sui (2009), "Effect of China's urban minimum living security system on incomedistribution and poverty", China Population Science, 2009, No. 5.

Li Xiaoyun, Zhang Keyun, Tang Lixia (2010): "Assessment of General Preferential Agricultural Policy and Its Poverty Reduction Effect", a background report prepared for the Evaluation Report of the Implementation Effect of "China's Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development Outline (2001-2010)".

NBS. 2010. China Rural Poverty Monitoring Report 2010. China Statistical Press.

Ravallion, Martin and Shaohua Chen, "China’s (Uneven) Progress Against Poverty", World Bank, June 16, 2004.

Sicular,Terry,YueXiming,BjörnGustafsson and Li Shi. 2005. The Urban-Rural Gap and Income Inequality in China. Discussion paper.

Wu Guobao, Guan Bing, Tan Qingxiang (2008), "Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Pro-poor Effect of National Food Subsidy Policy in Poverty-stricken Areas", "China Rural Poverty Monitoring Report 2008", National Statistics Press.

Yue, Ximing, Terry Sicular, Li Shi and BjörnGustafsson, 2005. Explaining Incomes and Inequality in China.Project Paper.

Zhang Dongsheng, (2010): "Annual Report on China’s Distribution of Income for Residents", Economic Science Press.

China Development Research Foundation (2007), "China Development Report 2007: Poverty Eradication in the Development", China Development Press.

Sato Hiroshi, Li Shi, YueXiming (2006), "Effect of Redistribution of Rural Taxation in China", "Economic Journal," August 2006.

[1]See ADB, 2007. “Inclusive Growth toward a Prosperous Asia: Policy Implications”, Working paper series.

[2]The Chinese government formulated the "12th Five-Year Plan", in which the government would make raised efforts to contain the widening income gap, rather than aim to reduce the income inequality.

[3]According to the estimates of the National Bureau of Statistics, in the late 1980s, the income inequality of urban residents was significantly higher than that in the early stages of reform, the Gini coefficient rose by 40% to 50% (Cheng Xuebin, 1996). For example, the National Bureau of Statistics estimated for monetary income of the urban residentsthe Gini coefficient of 0.23 in 1988; Gini coefficient estimated by income distribution project of the Institute of Economics of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences of personal disposable income (including in-kind income) is also 0.23 ( Zhao and Griffin, 1994).

[4]The rural poverty line was adjusted up in 2009. The lower poverty line is 889 yuan / day / person, and the upper poverty line is 1,196 yuan / day / person (see China Rural Poverty Monitoring Report 2010, the State Statistics Press).

[5] In 1978, when China was at the early stage of reform and opening up, the per capita income of urban residents was 343 Yuan and the per capita income of rural residents was 133 Yuan (see the "China Statistical Abstract 2008," p. 101). The former was 2.6 times that of the latter.

[6]Chen Xiwen, "Research on China's County Finance and Income Growth of Farmers", p. 117.

[7]In 1995, the per capita disposable income of urban residents was 3893 Yuan and the per capita net income of rural residents was 1578 Yuan (see "China Statistical Yearbook 1996", p. 238). This year, farmers' per capita tax and fee amounted to 5.3% of their net income, based on which we can calculate its effect on the income gap between urban and rural areas.

[8] This result is not incongruous with the national personal income figure. According to financial statistics, in 2008, a total of 372.2 billion Yuan of personal income tax was collected in nationwide. According to household survey data, based on the total number of 607 million of urban residents (population statistics from the Bureau of Statistics), the personal income tax paid by urban residents was only 162,1 billion Yuan, and it is impossible for the rural population to pay the remaining 200 billion Yuan of personal income tax. Of course, even if all personal income tax is from urban residents, the tax burden is only 3% of their income.

[9]Ministry of Civil Affairs, "2010 Social Services Development Statistics Report"(http://www.mca.gov.cn/article/zwgk/mzyw/201106/20110600161364.shtml)

[10]Source: Chinese Government Network, 2009-04-23

扫描下载手机客户端

地址:北京朝阳区太阳宫北街1号 邮编100028 电话:+86-10-84419655 传真:+86-10-84419658(电子地图)

版权所有©中国国际扶贫中心 未经许可不得复制 京ICP备2020039194号-2