Global Poverty Reduction and Development Forum-2012-Chapter V

Chapter V: China’s Population and Employment Policies for Inclusive Development

CAI Fang, WANG Meiyan

Institute of Population and Labor Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

Since China adopted the reform and opening-up policy in the late 1970s, along with its unprecedented economic performance, the social policy system has formed to support the inclusive development, characterized by giving priority to people’s livelihood and development sustainability. Such an inclusive social policy is manifested in the formation and implementation of family-planning policy and proactive employment policy.

This report is intended to illustrate how the family-planning program has coordinated population, resources and environment and how the employment policy has accomplished the tasks of full employment and sharing outcomes of the growth. The report also raises the urgent challenges facing the two policies and points out the direction of policy reform in the related areas.

1. Contents, Effects and Evolution of Population Policy

Family-Planning Policy and Its Intension of Putting People First

As early as in the 1970s, the Chinese government started to encourage “late marriage, longer interval between two births, and less birth”. In the early 1980s, the worldwide famous “one-child policy” was put into practice. This policy has so far been implemented for several decades and impacted the pathway of China’s development.

In 1991, the central government issued a document emphasizing the strict implementation of the family-planning policy, followed by introduction of provincial level legislation on family planning in all Chinese provinces. Because all provincial policy measures of implementing family planning were approved by the local Standing Committee of the People’s Congress, the family-planning policy officially became a nation-wide law.

The enhancement of the standard of living of the Chinese people has always been the primary objective for the policy formation and implementation. In the famous letter openly addressed to all Chinese youths on September 25th, 1980, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China explained the family-planning policy as an important measure relative to the speed and future of China’s modernization, to the health and happiness of future generations, inclusive of both short- and long-run interests of all Chinese people.

The promulgation of the strict family-planning policy in the early 1980s was consistent with Deng Xiaoping’s strategic thinking on the goal and roadmap for building a wellbeing society. In the late 1970s and the early years of the 1980s, Mr. Deng Xiaoping was devotedly engaged in studying, consulting and thinking about the feasibility of doubling the national output and achieving the wellbeing society (Yang, 2011). In the eve of the 13th National Congress of Communist Party of China in October 1987, he explained his famous “Three Steps Strategy” of China’s economic development to visiting foreign guests. As first step, China would have its gross national product (GNP) doubled in the period of 1981 and 1990, fulfilling the needs of food and clothing. As second step, total GNP would double again in the period of 1991 and the end of 20th century. And as a result, people’s living standard reached a level defined by wellbeing society. As third step, by the mid of 21st century, China’s per capita GNP would reach a level comparable to that in (middle high)? income countries, in which people become relatively rich and modernization basically accomplished.

In 2002, the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China embedded a period of building higher level wellbeing society into the “third step”. That is, by 2020, China will reach a specifically defined higher level wellbeing society in order to lay a solid foundation for reaching the final goal in the mid of 21st century. The coordination among population, resources, and environment is also viewed as a vital guarantee for building such a higher level wellbeing society.

From this brief review of the formation of Chinese family-planning policy, one can see that the ultimate intention of this policy is to help implement national strategies aiming to spur economic development and improve the standard of living of the Chinese people.

Changes in Implementation and Motivation of the Policy

Given that the Chinese population policy is intended to serve the people’s interests, the authority has been seeking incentives compatibility in implementing the policy. At the early stage of the implementation, because a large gap existed between the policy objective and households’ intention of fertility, administrators, who tirelessly implemented the policy, could only dissatisfy people. As fertility rate declined, the approach to implementing the population policy has become more and more incentive-oriented. In an attempt too avoid the disobedience of the policy, the administration at all levels has tried to implement the policy by providing more reproductive health services, establishing the interest-oriented mechanism related to family planning, enhancing incentives for family-planning, establishing social security programs conducive to population and development, and safeguarding various rights of women.

The existing population policy has been formulated by both national and regional legislations adjusted in accordance with the changes of population and socio-economic development through decades-long practice. Provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the central government have formulated their own policies and regulations according to local conditions. In fact, that some observers often regard China’s population as one-child policy is inaccurate. Due to the varieties of regional conditions in terms of social and economic development, fertility policies vary among regions, between rural and urban areas, and across ethnic groups. In general, regulations are easier in rural areas, the western regions, and for ethnic minorities. On average, the policy-required fertility rate is 1.47 for the country as a whole, and the one-child policy is only applicable to about 60 percent of the total population.

In the recent years, while the general policy is being smoothly implemented, some local governments have done some minor revision on local fertility policies. For instance, in all provinces, second birth is allowed for couples with both husband and wife being only child. In rural areas of 7 provinces, couples with either one being only child are allowed to have second child. Dozens of provinces canceled or eased interval requirement between two births, while the birth control for second marriage was deregulated in some other provinces.

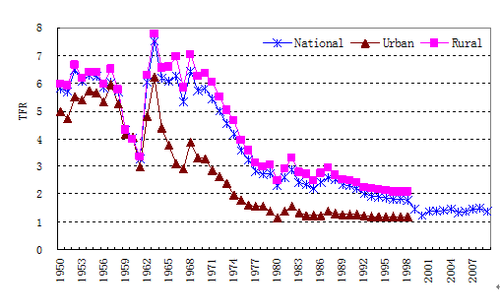

Unprecedented Demographic Transition and Fertility Decrease

Though the dramatic decline in total fertility rate (TFR) in China – namely, a drop from 5.8 to 2.3, happened in the period of 1970 to 1980, China was still at the stage with a TFR above the replacement level in the early 1980s. By virtue of the socio-economic development and implementation of family planning policy during the reform period, China has seen her fertility rate plummeting, with the high growth momentum held back. As can be seen in Figure 1, in the early of 1990s, TFR went down below the replacement level of 2.1.

Figure 1 Decline of Total Fertility Rates in Rural and Urban China

Source: data on TFR by region before 1998 is calculated based on database of China Center for Population Information; data on national TFR after 1998 is calculated based on various population survey or census

In Figure 1, the yearly figures of national TFR before 1998 was the level the government officially admitted and that after 1998 was the level scholars trust to be true. From the Figure, one can see that the TFR of China is below 1.5 for many years, a very low level in international comparison (Gu and Li, 2010). According to the United Nations (2010), China’s TFR was 1.4, a level lower than the World average (2.6), the average of developed countries (1.6), and the average of less developed countries after excluding the least developed countries (2.5).

Impacts of Demographic Dividend on Economic Growth

In the entire period of the dual economic development since the reform and opening-up policies initiated in the late 1970s, China’s unprecedented rapid growth has benefited substantially from the demographic dividend, which can be predicted by economic theory and proven by the Chinese experience. The impact of demographic transition on economic growth can be understood by contributive sources of the growth.

Firstly, the declining dependency ratio contributes to the capital formation necessarily conditional for the rapid economic growth, which helps China maintain high savings rate. In addition, sufficient supply of labor prevents diminishing returns on capital. Such a determinant of growth can be embodied in the contribution of the fixed assets formation in production function estimation.

Secondly, the continuing rise of working age population guarantees adequate supply of labor and that, together with the enhancement of years of schooling of workforce, endows China with strong competitive advantage while participating in the economic globalization. The impacts of those factors on growth can be manifested by contributions made by labor growth and increase in years of schooling of labor force.

Thirdly, in the reform period, the massive labor migration from low productivity (e.g. agriculture) sector to high productivity (non-agricultural) sectors creates resources reallocative efficiency, which is a major source of the improvement of the total factor productivity.

Finally, the declining population dependency ratio – namely, the ratio of dependent population to working age population, which can be viewed as a proxy of pure demographic dividend, contributes to the fast economic growth in the period of dual economy development.

An estimation of production function on the Chinese economic growth since the early 1980s decomposes the relative contribution made by each of the relevant variables, including fixed assets formation, total employment, years of schooling of employed workers, dependence ratio, and residual. The findings show that the GDP growth in the period of 1982 to 2009, 71 percent was attributed by capital input, 7.5 percent by labor input, 4.5 percent by human capital, 7.4 percent by decline of dependence ratio, and 9.6 percent by improvement of total factor productivity (Cai and Zhao, 2012).

2. Proactive Labor Market Policies and Their Effects

To reap demographic dividend from favorable population structure is preconditioned by full employment. During the period of economic reform and opening-up, especially after the entry to WTO, China has witnessed the largest labor migration and the fastest expansion of employment, to which the proactive employment policy and labor market reform contribute significantly.

Formation and Perfection of Proactive Employment Policy

With long-term practice, hard efforts, and even painful price, the framework of proactive employment policy was gradually established in China. Prior to the late 1990s when employment system began to reform, the labor market mechanism of urban employment played a marginal role in allocating new entrants with in the state and collective sectors absorbed majority of urban laborers. At the time, economic growth was considered synonymous of employment expansion. Employment per se was not put as an independent target of macro-economic policies. In the expressions of objectives of monetary and fiscal policies, employment was not explicitly mentioned[1].

In the late 1990s when the economic growth slowed down caused by the East Asian financial crisis, state enterprises encountered severe operational difficulties and had no choice but to lay off workers, which caused unprecedented massive unemployment. To tackle the situation and secure people’s livelihood, the government started to implement the proactive employment policy by introducing a host of policy measures in promoting employment and re-employment. Meanwhile, employment became an important goal of the macro-economic policies. Such a proactive employment policy has been realized through managing macro economic, training and assisting job search, stimulating demand for labor force, and strengthening ability of the economic growth to absorb employment.

In his speech titled “Employment Is the Base of People’s Livelihood” at the National Conference of Re-employment, September 12, 2002, the Chinese President Jiang Zemin prioritized employment. As he pointed out, tackling the employment problem is a test of the ability of governance of the Party and the government. In the same year, the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China announced that the state implements long-term strategies and policies to promote employment, listing expanding employment as one of the four macro-economic policy objectives, along with spurring economic growth, stabilizing prices, and maintaining balance of international payments. In all official announcements and documents, employment is put as priority of economic and social developments.

In tackling the negative impacts of the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, the Chinese government implemented more proactive employment policies and accomplished the objective of economic growth, people’s livelihood, and social stability through stabilizing employment expansion. More proactive employment policy and its key focus and major targeted groups are clearly written into China’s 12th Five-year Plan.

Labor Market Development and Employment Expansion

China’s rapid economic growth has always been accompanied by tremendous employment expansion (Cai, 2010). Some researchers conclude that the economic growth and employment expansion in China have not been isochronous, because they are puzzled by the incompleteness and inconsistency of the employment statistics. First, migrant workers are not included in the number of urban employment. Out-migrants from their home townships for more than 6 months were accumulated to 158.6 million in 2011(DRSES-NBS, 2012). Second, since the late 1990s urban informal employees have emerged, dominated by new entrants and re-employed laid-off workers. Because they are not included in statistics of sectoral and regional employment, any disaggregated analysis on employment cannot but miss them. In 2009, over 90 million of urban resident employees were in this category, accounting for 28.9 percent of the total[2]. In addition, rural laborers engaged in non-agricultural sectors of local townships are often ignored by researchers. While the numbers of this category remain little changed, their stock should not be neglected. In recent years, the stable employment in such category totals to nearly 100 million.

In order to show a relatively complete picture of employment and labor demand and supply, we try to explore the actual employment of urban sectors, which can be taken as a proxy of labor demand. Since the numbers of laborers engaged in agriculture are in a declining trend and the non-agricultural sectors in rural areas are not expected to expand, the increase of urban employees with the inclusions of informal and migrant workers can well represent the overall demand of the Chinese labor economy.

By combining various sources of employment data, we found that in 2009, 12.5 percent or 39 million of 310 million reported urban employees were migrant workers, which is much lower than the actual number of migrants. If we assume that urban labor survey in 2000 does not cover migrants and the proportions of migrants in urban labor survey in the following years increased at the same speed and it increased to 12.52 percent in 2009, we can get the proportions of migrants in urban employment statistics each year. And we can calculate the number of urban resident employees, which does not include migrants.

The total number of migrant workers, who are defined as out-migrants from their home townships for more than 6 months, was accumulated to 145 million in 2009, of which 95.6 percent migrated to cities. We assume that the distributions of migrant workers between urban and rural areas during the period of 2000 to 2011 are the same as that in 2009. Based on this, we can calculate the annual number of migrant workers in cities according to data from monitoring survey reports on migrants by the National Bureau of Statistics. Then we can compare the number of urban resident employees and migrant workers with that of working-age population of the country as a whole (Table 1).

Table 1 Demand for and Supply of Labor Force (ten thousand, %)

|

|

Urban resident employment (1) |

Migrant workers in cities (2) |

Working-age population (3) |

Demand-supply ratio (1+2)/(3) |

Demand-supply elasticity Δ(1+2)/Δ(3) |

|

2001 |

23607 |

8029 |

88536 |

35.7 |

- |

|

2002 |

24091 |

10009 |

90070 |

37.9 |

4.5 |

|

2003 |

24569 |

10889 |

91399 |

38.8 |

2.7 |

|

2004 |

25003 |

11303 |

92893 |

39.1 |

1.5 |

|

2005 |

25430 |

12025 |

94352 |

39.7 |

2.0 |

|

2006 |

25947 |

12631 |

95234 |

40.5 |

3.2 |

|

2007 |

26492 |

13094 |

96009 |

41.2 |

3.2 |

|

2008 |

26848 |

13423 |

96757 |

41.6 |

2.2 |

|

2009 |

27224 |

13894 |

97419 |

42.2 |

3.1 |

|

2010 |

27669 |

14627 |

98059 |

43.1 |

4.4 |

|

2011 |

27955 |

15165 |

98622 |

43.7 |

3.4 |

Source: authors’ own calculation based on data from China Statistical Yearbook (various years), China Yearbook of Rural Household Survey (various years), and China Population Yearbook (various years) and Du and Hu (2011).

From the table, one can see that in the period of 2002 to 2010, the growth of total urban employment – that is, the sum of urban resident employment and migrant employment, was faster than the growth of working age population of the country as a whole, which implies that China’s economic growth is not one without employment growth. On the contrary, urban employment expansion accompanied by urbanization can not be ignored. As a result of active employment policies, rural surplus laborers, urban unemployed and redundant personnel have decreased significantly.

Labor Mobility: The Effect of Alleviating Poverty and Raising Income

The expanded opportunity of rural laborers in non-agricultural sectors has reduced the rural poverty and blocked, if not completely eliminated, the rural urban income gap from further widening. The household responsibility system, which is characterized by the even distribution of farmland among households and equal rights of residual claimants of farm production, guarantees the free choice for rural laborers in search of higher pay and better life. Therefore, even if the wage rate had remained unchanged for many years, the expansion of migration scale could sufficiently increase the farmers’ income, which can be observed from three aspects.

A first is to examine the effect of migration on poverty alleviation. Except for those who lack labor force, most households fell into poverty and suffered from the lack of employment opportunity. Studies show that in general it is easier for those with skills and/or networks to find non-agricultural employment in rural areas, whereas poor households do not have such skills and network necessary for grasping the employment opportunity in rural areas. Rural-to-urban migration, therefore, is relatively a democratic opportunity for the poor to participate in labor market and earn higher income. Du et al. find that poor households, by migrating out of rural areas, can gain 8.5 to 13.1 percent increase in per capita income (Du, Park and Wang, 2005). However, households short of labor force hardly benefit from migration.

A second is to look at the contribution of wage income to the increase of total household income. According to the categorization of National Bureau of Statistics, net income of rural households consists of wage income; income generated by households’ business operation, income from properties and transferred income. The massive expansion of non-farm employment via labor mobility has significantly enhanced the share of wage in households’ income, contributing overwhelmingly to income growth of rural households. Official statistics show that the share of wage in rural households’ income increased from 20.2 percent in 1990 to 41.1 percent in 2010, while wage income contributed 48.3 percent to the increase of households’ income in 2010[3].

A third is to note that a significant part of migrants’ earnings are missing from official statistics. When National Bureau of Statistics conducts the household surveys in rural and urban areas separately, on the one hand, migrant households are excluded from the chosen samples of urban households because they usually do not have stable housing in destination cities and therefore they are not considered as practical survey samples. On the other hand, they are excluded from the chosen samples of rural households because they have been away from their hometowns for a long time and are usually not considered as rural usual residents. As is explained in the notes on main statistical indicators of China Statistical Yearbook, those family members who left home for 6 months or more are not considered as usual rural residents, unless they keep close economic relation with their family by sending the majority of income to the household. While the exception as described as “close economic relation” is practically hard to define, those permanently live and work outside registered places usually are not counted as rural usual residents and their income is omitted from rural households’ survey.

Therefore, migrant workers’ income is significantly underreported. Some researchers found the trend of income distribution improvement by digging and revising incomplete statistics. Trying to avoid the flaw of the present household surveys conducted separately between rural and urban areas, Gao et al. selected some households, including National Bureau of Statistics samples and others, in Zhejiang, a developed province and Shaanxi, a relatively underdeveloped province to observe the degree to which the migrant workers’ income is being underreported. This study concludes that the existing imperfection of the statistical definition in surveying households’ income alone leads to overestimation of urban residents’ income by 13.6 percent and underestimation of rural households’ income by 13.3 percent. That is, the income gap between rural and urban households has been overstated by 31.2 percent (Gao et al., 2011).

The Building of Labor Market Institutions and Workers’ Rights

In the process of coping with mass unemployment and lay-off in the late 1990s, proactive employment policy was formed, including wider covered social safety net, employment-oriented macro-economic policies, active assistance to re-employment, and provision of public employment opportunities. Starting with tackling the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, the Chinese government has strengthened the proactive employment policy by introducing more policy measures to help stabilize employment. One of such measures is to focus on providing special assistance to migrant workers, college graduates, and urban vulnerable workers.

As China passed through its Lewis turning point characterized by significant reduction of surplus laborers in agriculture, labor shortage becomes widespread in all sectors. At the same time, the favorable policies towards agriculture, rural areas and farmers have enhanced profitability of farming, which helps strengthen bargaining power of migrant workers in employment relations and thus leads to increase in wages in all sectors, wages convergence, and improvement of working treatment.

Since 2004, through various efforts made by the central and local government such as legislation, regulation, enforcement of laws, and adjustment of policies, the policy climate for migrants to work, live, and receive equal treatments of public services in cities has been significantly improved. Though the institutional changes and policy adjustment have been far from completion, to those who have closely observed the entire process of labor migration from rural to urban areas, it might be well agreed that since the year of 2004 signaling the Lewis turning point, labor migration policy has entered its golden age (Cai, 2010).

Meanwhile, the central government has actively advanced legislation and law enforcement to regulate the labor market and strengthen social protection, while local governments have raised the level of minimum wages with great enthusiasm under the requirement of the central government, which helps form a normal mechanism of wages growth.

3. Demands for Policies at New Stage of Development

China’s rapid economic growth has typically been characterized by duality since the beginning of the 1980s. The demographic transition has been accompanied by massive migration of rural surplus laborers and expansion of urban employment. With the coming of the new stage of China’s demographic transition and economic growth, the economic growth pattern will be transformed after a series of turning points.

The Coming of Two “Turning Points”

Labor shortage has first appeared in the coastal areas in 2004 and has become widespread all over the country since then. In 2011, most manufacturing enterprises suffered difficulties in recruiting workers. When the growth of labor supply has slowed down, the demand of China’s economic growth for labor still remains strong. The urban employment has been growing rapidly. China is moving away from unlimited supply of labor. The marginal productivity of labor in agriculture is not as low as the theory assumes any more. The wage is not determined by subsistence wages and it is more sensitive to labor supply and demand.

The rise in wage rates of migrants accelerated since 2004 after a long stagnation. It began to increase at an annual rate of 12.7 percent in the period of 2004 to 2011[4]. Manufacturing and construction are characterized as employing unskilled workers. In the period of 2003 to 2008, the annual growth rates of wages were 10.5 percent and 9.8 percent, respectively in these two sectors[5]. In the period of 2003 to 2009, the annual growth rates of daily wages of paid workers in grain production, cotton production and in pig farm with 50 pigs or more were 15.3 percent, 11.7 percent and 19.4 percent, respectively[6].

According to the definition of development economics, the emergence of widespread labor shortage and constant increase of wages for unskilled workers imply that China has reached the Lewis turning point. Though there are different opinions on this judgment and on whether the Lewis model is applicable to China, the big challenges to China’s economic growth posed by these changes need more attention.

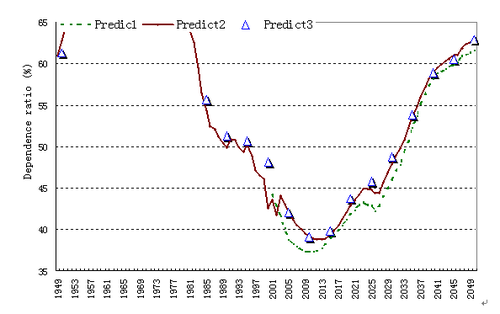

The long lasting low fertility gives rise to a change in population age structure. That is, though the number of working-age population aged 15 to 64 has been growing but its growth has slowed down. The year 2013 is China’s turning point at which the working-age population will stop increasing and begin shrinking afterwards. At the same time, population dependency ratio (ratio of dependent population to working-age population) will decrease to the lowest point and afterwards it will start increasing rapidly (Figure 2). Many researchers take population dependency ratio as the proxy indicator of demographic dividend. The reversal of population dependency ratio trend is the turning point when demographic dividend will disappear.

Figure 2 Increased Dependency Ratio Implies the Disappearance of the Demographic Dividend

Source: Prediction 1, 2 and 3 are done by HU Ying, WANG Guangzhou and United Nations, respectively.

Taking 2004 as the Lewis turning point and 2013 the representative year at which demographic dividend disappears, one can understand the unique feature of China’s demographic transition – namely, growing old before getting rich, by observing the interval of time between the two turning years in comparison with other East Asian countries. According to studies on turning point, the Japanese economy passed through their turning point in 1960 (Minami, 1968) and Korean economy passed through theirs in 1972 (Bai, 1982). The population data shows that dependency ratio began to rise in Japan in 1990 and in Korea in 2013. That is, the time span between the Lewis turning point and demographic turning point is 30 years for Japan, over 40 years for Korea, and less than 10 years for China.

Taking 2004 as the representative year of the arrival of the Lewis turning point and 2013 as the representative year of disappearance of demographic dividend is a useful approach to understand the challenges facing the Chinese economy. Apparently, the length between the two turning points has something to do with the Chinese characteristics of the demographic transition, and it raises an alert for China to tackle the resulting challenges.

New Trends and New Tasks of Labor Market

The coming of the Lewis turning point implies that the labor market gradually transforms from a dual to a mature one. In a developed market economy, employment pressure is mainly reflected by three types of unemployment, which are cyclical unemployment caused by macro economic fluctuations, structural unemployment caused by mismatching between labor skills and employers’ demand and frictional unemployment caused by time costs of job searching. Structural unemployment and frictional unemployment are called natural unemployment. Natural unemployment usually is persistent and its level is relatively stable in long run. China will more and more be faced with these three types of unemployment.

Under conditions of typical market economy, the cyclical fluctuation of macro economy is inevitable and cyclical unemployment is inevitable correspondingly. At the current stage, rural laborers migrating to cities have no stable jobs and usually suffer more from cyclical unemployment since they do not legitimately have urban hukou. For example, the shock caused by the financial crisis in 2008 on China’s real economy and employment made millions of migrant workers returning home ahead of schedule before 2009 Spring Festival, which is a reflection of cyclical unemployment.

With the acceleration of industrial restructuring, some traditional jobs will inevitably disappear when some new employment opportunities are created. If the skills of workers who need to change jobs can not meet the requirements of new posts, these workers will be faced with the risk of structural unemployment. Since China’s labor market has not been developed very well and the allocating mechanism of human resources is still imperfect, frictional unemployment also exists. The new entrants including all kinds of graduates need time to match their skills with the demand of labor market. The urban laborers with deficiency of human capital and new skills need more time to meet the labor market demand. These two groups are more likely to suffer from structural unemployment and frictional unemployment.

Challenges Posed by Population Structure

Thanks to the implementation of strict family planning policy and economic development, the quantity of China’s population has effectively been controlled. However, challenges faced by population structure gradually emerged, which are mainly reflected on the following aspects:

First, sex ratio at birth has kept at a high level. Sex ratio at birth is the ratio of boys to girls at the time of birth. Since the fourth census in 1990, this ratio in China has been exceeding the normal level significantly. It was 119.5 in 2009, that is, boys were more than girls by 19.5 percent. Gender discrimination on the labor market and imperfect social security system are two important reasons for gender imbalance.

Second, population aging has been speeding up. On one hand, population aging is the outcome of economic and social development and an irreversible trend of population development. “Aging society” with high share of old people will be the normal situation of the society we have to be faced with. On the other hand, China’s “aging before affluence” brings about severe challenges for the ability of providing for the aged, social security system and economic and social development, which needs to be actively addressed. We should accelerate the improvements of the basic pension system covering both urban and rural residents. The consensus on providing for and respecting the aged and the ability of providing for the aged should be improved. “Active, healthy, secure and harmonious” strategy should be implemented to cope with population aging.

Third, population quality can not meet the demands of economic and social development. The educational levels of Chinese people are still pretty low. The illiteracy rate of population aged 15 and above was 7.8 percent in 2008 and the average years of schooling was only 8.5 years. The total incidence of monitoring birth defects has been increasing. The share of kids with visible congenital abnormality at birth and with defects appearing gradually after birth is 4 to 6 percent. And the annual number of kids with defects is about 800 thousand. All kinds of disabled persons are 82.96 million. The situation of reproductive health is not optimistic.

4. Policy Revisions Focused on the Comprehensive Development of the Population

The formation of the family planning policy characterized by one-child policy was closely related to the planning economy and the dualistic economic structure. It has its inevitability and the branding of the ages. To express this in today’s language, the original intention of this policy was to release demographic dividend to the largest extent in short run. China is on a new stage of economic development and demographic transition and the population has been changing greatly. A new population situation is forming.

We should conform to the principle of maintaining sustainable economic growth and improving the standard of people’s lives when we think about future policy direction in order to carry out population and family planning comprehensively. To realize balanced development of population and make it really become an active factor of sustainable development, we need to start from many aspects such as population quality, structure and quantity. Namely, we have to achieve significant improvements of population quality, reasonable age structure and sex ratio and the sustainability of population quantity. In what follows we put forward some policy suggestions from three perspectives including educational development, tackling population aging and family planning policy.

Improving Human Capital Comprehensively

With the disappearance of the first demographic dividend, the traditional factors driving economic growth need reallocated and economic growth sources which are more effective in the long run and will not produce diminishing returns needed to meet higher requirements. Especially, tapping and creating the second demographic dividend to avoid falling into middle income trap requires improving the overall human capital level of the nation significantly.

First, compulsory education lays the foundation of lifelong learning. It is the key of forming the same starting line for kids between urban and rural areas and between families with different income. The governments have unshirkable responsibilities to invest on it sufficiently. Preschool education has the highest social return rate. The governments paying for it conforms to education law and the principle of benefiting the whole society. Preschool education should be brought into compulsory education.

In recent yeas, with the increase of job opportunities, there are strong demands for unskilled workers. Some kids, especially those from poor rural families, drop from junior high school. The governments should make earnest efforts to reduce the proportion of family spending on compulsory education and consolidate and improve the completion rate of compulsory education. Bringing preschool education into compulsory education to make poor and rural kids not lose at the starting line is helpful for improving their completion rates of primary school and junior high school and increasing equal opportunities of going on to higher levels of education for them.

Second, improving the enrollment rate of senior high school significantly and promoting mass higher education. The enrollment rate of senior high school and that of higher education promotes and interacts with each other. The number of students who are willing to go to college will be bigger if there is a higher enrollment rate of senior high school. More opportunities of entering college will motivate kids to go to senior high school. At the current stage, the low proportion of government budgetary funds on senior high education, the heavy burden of family expense, high opportunity costs and the low success rate of entering college make high school education become the bottleneck of future education development (Cai and Wang, 2012). Therefore, starting from keeping on accelerating mass higher education, the governments should promote free senior high education as soon as possible. Comparatively speaking, we should bring into play the roles of running schools by non-government sectors and family investment in higher education.

Finally, making great efforts to develop vocational education by labor market guidance. China needs a group of high skilled workers, which depends on secondary and higher vocational education to cultivate. The share of receiving vocational education of students at the right age is usually more than 60 percent in European and American countries and sometime up to 70 to 80 percent in countries like Germany and Switzerland, which are significantly higher than China. Starting from the requirements of medium and long-term development on labor quality, China should devote more efforts to promote development of vocational education and training. In addition, the entrance channels between secondary vocational education, higher vocational education and higher academic education should be established. The reform on education system, teaching model and content should be accelerated to make students have more choices to achieve comprehensive development.

Coping with Population Aging Actively

Population aging has been accelerating in China. By the end of the 12th Five-year period, China will still be at the stage of middle income. Meanwhile, old people aged 60 and above will exceed 200 million, accounting for 15 percent of the total population. To achieve sustainable growth, China needs to tackle the severe challenge s brought about by aging before affluence.

First, improving social pension system to cover urban and rural residents and migrants and, upgrading the standard of its security and social pool. We should achieve the overall coverage of social pension system on urban and rural residents as soon as possible, make great efforts to develop social services for the old people and guarantee, gradually improve the living standard of elderly persons of no family and elderly persons with disabilities. Population aging affects thousands of families and concerns social harmony and the sustainability of development. Under the circumstance of the governments providing the related basic public services, we should comprehensively improve the abilities of society, family, community and aging industry to provide for the aged. We should also promote the establishment of old-age service system, which is supported by secure funding and service and focused on solidifying family care for the aged, enlarging community support, improving service ability of institutions and promoting the development of aged service industries.

Second, creating conditions to tap new consumption demand brought about by population aging and transforming it into a driving force of economic development. The old people are special consumption groups. They have spiritual and cultural demands including bodybuilding and leisure and material demands including family care for the aged and social service for the aged. Their demands should be supported and encouraged by the state from some aspects such as fiscal policy, taxation policy, financial policy and business administration policy. These demands caused by population aging and easy to grow should be made to promote generating some new service sectors and to become a new driving force of economic development.

Finally, developing human resources of the aged rationally, creating jobs suitable for the aged and exploring flexible retirement system. According to a study, in the range of ages between 24 and 64, each additional age of 1 year reduces the years of schooling by 10.2 percent. Such a negatively marginal effect becomes more significant at older ages – in the range of 44 to 64, every additional age of 1 year reduces the years of schooling by 16.1 percent (Wang and Niu, 2009). It is obvious that the condition of raising retirement age is still not mature and it needs to be created through developing education and training, so that the participatory rate of the aged can be improved in the future to alleviate the problem of the insufficient social resources providing for the aged and to extend the period of the demographic dividend.

Gradually Perfecting Population Policy

Under the guidance of scientific outlook of development – namely, putting the people first, the Chinese population policy should be adjusted in accordance with changed situation. Though demographic transition has been ultimately driven by economic and social developments and the trend of population aging shall not be reversed, the alteration of population policy can to certain extent contribute to balance the population structure.

However, there are reasons for the population policy adjustment – namely, relaxing the one-child policy to allow families to decide the desired numbers of children, since population size no longer imposes any significant pressure on China.

Firstly, there exists the difference between policy fertility and intended fertility, which can provide a room for China to balance its population age structure in the future. According to surveys on childbearing intention conducted in 1997, 2001 and 2006, the intended fertility rate is 1.74, 1.70 and 1.73, respectively (Zheng, 2011). That is, comparing to the current policy-allowed fertility rate of 1.5 and actual fertility rate of 1.4, such a childbearing intention means that the birth rate can be moderately increased if the policy relaxes in the near future.

Second, the one-child policy has in essence accomplished its initial goal. In 1980, when the Chinese leadership formally announced the policy, it was to be implemented as a one-generation policy. As the official document puts it, “in 30 years from now, at present, extremely intense problem of population growth mitigates, an alternate population policy shall be carried out then.” Since the condition of “alternate population policy” has been much more mature than it was expected at the time, the policy adjustment has its sufficient legitimacy today.

Third, local experiences in adjusting the one-child policy have revealed the pathway and roadmap of reform. While the family-planning policy is implemented in nation wide, local governments have some autonomy to decide policy details in conformity to local specific situation. Presently, overwhelming majority of the Chinese regions enforces the policy that allows married couples both from only-child families to give birth to second child. When the policy relaxation gradually evolves to allow married couples either from only-child families to give birth to second child, the spectrum covered by the new policy will be sufficiently widened.

Creating Institutional Conditions to Achieve Gender Equality

The discrimination against females in the labor market and raising sons for old age as a result of the imperfect social security system are two important reasons for gender imbalance. A comprehensive approach to address both the symptoms and root causes should be adopted to solve this problem. The rising trend of sex ratio at birth could be effectively curbed through promoting gender equality, eradicating gender discrimination in employment, improving social pension system and eliminating birth gender preference.

The enforcement of Employment Promotion Law should be enhanced in order to eradicate the discrimination against females in the labor market. The discrimination against females in the labor market usually takes two forms: wage discrimination and employment discrimination. Wage discrimination means that female workers are paid lower wages than male workers who have the same jobs and productivity. Employment discrimination means that female workers who have the same productivity as male workers are assigned jobs with lower wages by their employer and male workers are assigned jobs with higher wages. The supervision of the implementation of labor laws and regulations should be strengthened and equal opportunities be created in order to eliminate wage differentials between females and males with the same jobs. In addition, labor market should be developed actively and institutional barriers and access to jobs should be reduced.

5. Implementing More Inclusive Employment Policy

With the coming of the Lewis turning point and the turning point of the demographic dividend, quantitative contradictions of China’s employment are gradually transformed into structural contradictions. This transition brings new connotations to proactive employment policy, putting forward new tasks of enhancing its inclusiveness. In what follows we make some policy recommendations from focus changes of employment policy, integration of labor market and the building of labor market institutions.

The Transition of the Focus from Quantity to Structure

To cope with the increasingly prominent cyclical, frictional and structural unemployment, the first principle we should follow is to put employment first in the formulation of macro-economic policies and to establish policy directions and policy intensity based on employment situation, reducing the risk of cyclical and natural unemployment. In the 12th Five-year Plan, the central government’s expression on employment importance elevates from requiring putting employment expansion in a more prominent position in economic and social development to implementing the strategy of developing employment first.

In order to implement the principle of developing employment first, in the overall requirements of macro control, we should not only consider the goal of GDP growth, but also should directly declare the goal of employment growth and the goal of controlling surveyed unemployment rate which could reflect the level of cyclical unemployment. To achieve the goals of employment growth and unemployment control, on one hand, we should set a rational speed of economic growth and take maximizing employment as an important consideration when establishing policy direction, policy measure and policy intensity of macro control, reducing the shocks of economic fluctuations on employment. On the other hand, we should take expanding employment as the common goal and enhance coordination and cooperation of macro economic policies such as financial policy, monetary policy and tax policy to better meet the needs of reducing unemployment rate.

While quantitative contradictions of China’s employment have been alleviating, structural and frictional employment difficulties can not be neglected. The new entrants including various types of graduates and urban residents who have difficulties in employment and lack of new skills are more likely to suffer from structural and frictional unemployment. This is the most suitable area that the governments play their roles in promoting employment, which puts forward higher demands for labor market function and governments’ ability of providing public services. It requires governments to provide training on searching for a job, starting a business and changing jobs and on-job training and to regulate and improve the function of human resources market, reducing natural unemployment rate from improving the ability of workers and improving market allocation efficiency.

Promoting the Integration of Urban and Rural Employment

A labor market, in which workers can migrate freely and their legitimate employment rights can be well protected, is the institutional guarantee of a country transforming from a middle income to a high income one. At present, there still exist many institutional barriers deterring labor mobility, including segregation between urban and rural areas, segregation among regions and different hukou status, which hinders the equalization of employment opportunities as well as reasonable and efficient allocation of human resources. We should remove these barriers as soon as possible, promote equal employment between urban and rural workers and further improve labor market mechanism. Therefore, we should continue to follow the principle of balancing urban and rural development, further improve related policies and deepen institutional reform, promoting rural laborers to migrate to work stably.

The establishment of reform objectives to achieve institutional reform and the implementation of policies should put the emphasis on the areas related to including migrants in social security system and obtaining equal access to public services. At present, China’s urbanization rate is calculated based on the statistics of usual residents, reaches 51 percent. However, the share of people with non-agricultural hukou is only 34 percent, implying that migrants are still excluded from equitable entitlement to urban basic public services. The central government has clearly demanded to deepen household registration system reform and to lower the thresholds for residence in medium-sized and small-sized cities, making migrants who have stable jobs and residing places become urbanites.

From the principle of compatible incentives, one measure that city governments can use to promote urbanization is to provide more stable security and protection for migrants’ employment through the building of labor market institutions. On the basis of this, they should gradually extend institutional building to wider areas of public services and achieve real urbanization and the synchronization of urbanization and non-agriculturalization, passing through the Lewis turning point and completing the conversion of dual economic structure.

The Building of Labor Market Institutions and Social Protection

An obvious signal of the arrival of the Lewis turning point is the dramatic changes of labor relations. With the new situation of labor supply and demand, workers’ consciousness of protecting their rights such as higher wage rate and better working conditions are enhancing. Partial conflicts between workers and employers will inevitably emerge when enterprises lack the capability and insufficient willingness to adapt to the situation. Faced with “the growing pains”, the problems cannot be solved if we simply steer clear of them or take populist policies. We must rely on institutional building to pass through the stage of middle income.

Since collective bargaining system is worried about more or less, it becomes a weak point of the building of labor market institutions. Actually, based on China’s current institutional framework, constructing collective bargaining system on wages and working conditions is more controllable and more easily to achieve active outcomes, compared with European and American countries. Through a mechanism in which the trade unions represents the rights of workers, the federation of entrepreneurs represents the rights of employers and the governments guide, coordinate and negotiate, we can explore a pattern of labor relations with Chinese characteristics.

Social protection has much broader functions than labor market institutions. In accordance with the idea of constructing a harmonious society, we can combine labor market institutions, social security systems and other social welfare systems to form a public service system adapting the socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics, achieving and guaranteeing “putting people first” through institutions. After the arrival of the Lewis turning point, with labor shortage gradually becoming constraint of economic growth, the developmental and competitive types incentives of Chinese government can be transformed into incentives to strengthen social protection for workers and residents.

References:

Bai, Moo-ki (1982), “The Turning Point in the Korean Economy”, Developing Economies, No.2, pp.117-140.

Cai, Fang (2009), “Discussions on the Priority of Employment in Social and Economic Development Policy”, in Collected Papers of Cai Fang, China Publishing Group, Zhonghua Book Company.

Cai, Fang (2010), “The Formation and Evolution of China’s Migrant Labor Policy”, in Zhang, Xiaobo, Shenggen Fan and Arjan de Haan (eds) Narratives of Chinese Economic Reforms: How Does China Cross the River? New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd..

Cai, Fang and Meiyan Wang (2012), “On the Status Quo of China’s Human Capital: How to Explore New Sources of Growth after Demographic Dividend Disappears”, Frontiers, No.6.

Cai, Fang and Wen Zhao (2012), “When Demographic Dividend Disappears: Growth Sustainability of China”, in Masahiko Aoki and Jinglian Wu (eds) The Chinese Economy: A New Transition, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming.

David E. Bloom, David Canning and Jaypee Sevilla (2002), “The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change”, Santa Monica, CA, RAND.

Department of Rural Social and Economic Survey, National Bureau of Statistics (DRSES-NBS), China Yearbook of Rural Household Survey 2012, China Statistics Press.

Du, Yang and Ying Hu (2011), “Working-age Population Projection in Urban and Rural Areas”, unpublished paper.

Du,Yang, Albert Park and Sangui Wang (2005), “Migration and Rural Poverty in China”, Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol.33, No.4, pp. 688-709.

Gao Wenshu, Wen Zhao and Jie Cheng (2011), “The Impact of Rural Labor’s Migration on Income Gap Statistics of Rural and Urban Residents”, in Fang Cai (eds) Reports on China’s Population and Labor (No. 12): Challenges during the 12th Five-year Plan Period: Population, Employment, and Income Distribution, Social Sciences Academic Press.

Gu, Baochang and Jianxin Li (2010), The Debate on China’s Population Policy in the 21st Century, Social Sciences Academic Press.

Hu, Ying, Fang Cai and Yang Du (2010), “Population Changes in the 12th Five-year Plan Period and Projection of Future Population Development Trends”, in Fang Cai (eds) Reports on China’s Population and Labor (No. 11): Labor Market Challenges in the Post-Crisis Era, Social Sciences Academic Press.

Minami, Ryoshin (1968), “The Turning Point in the Japanese Economy”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol.82, No.3, pp.380-402.

United Nations (2010), World Fertility Pattern 2009, downloaded from http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/worldfertility2009/worldfertility2009.htm.

Wang, Guangzhou and Jianlin Niu (2009), “Composition and Development of the Chinese Education System”, in Fang Cai (eds) Reports on China’s Population and Labor (No. 10): The Sustainability of Economic Growth from the Perspective of Human Resources, Social Sciences Academic Press.

Wang, Meiyan (2011), “Urban Employment, Non-agricultural Employment and Urbanization”, in Fang Cai (eds) Reports on China’s Population and Labor (No. 12): Challenges during the 12th Five-year Plan Period: Population, Employment, and Income Distribution, Social Sciences Academic Press.

Yang, Fengcheng (2011), “A Discussion on Deng Xiaoping and the Formulation of ‘Three Steps Strategy’”, Guangming Daily, August 3.

[1] See a summary in Cai (2009).

[2] Calculated according to data from China Statistical Yearbook 2010.

[3] Calculated according to data from China Yearbook of Rural Household Survey.

[4] Calculated according to data from China Yearbook of Rural Household Survey.

[5] Calculated according to data from China Labour Statistical Yearbook.

[6] Calculated according to data from Compilation of National Farm Product Cost-Benefit Data.

扫描下载手机客户端

地址:北京朝阳区太阳宫北街1号 邮编100028 电话:+86-10-84419655 传真:+86-10-84419658(电子地图)

版权所有©中国国际扶贫中心 未经许可不得复制 京ICP备2020039194号-2