Global Poverty Reduction and Development Forum-2013-Chapter II

Chapter II: China's Labor Migration and Urban Poverty

Meiyan Wang

Institute of Population and Labor Economics

Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

1. Introduction

Before the reform and opening-up in 1979, labor migration between urban and rural areas was restricted by the household registration system. All urbanites of working age were entitled to and provided with assigned jobs by the government. The urban poor mainly consisted of people with no working ability, no income and no family support (Cai et al., 2005). Before the 1990s, most of China's poor were from rural areas. An estimation from a household survey shows that 12.7 percent of the rural population were poor in 1988 and only 2.7 percent in urban areas. In 1995, the poverty rates in rural and urban areas were 12.4 percent and 4.1 percent respectively (Riskin and Li, 2001; Khan, Griffin and Riskin, 2001). This situation has not changed much in recent years. A study shows that the contribution rates of rural and urban poverty to multi-dimensional poverty were 75.5 percent and 24.2 percent respectively in 2009 (Wang, 2012).

Urban poverty cannot be ignored, especially with the emergence of unemployment issues. The urban poor include poor residents and poor migrant populations. Since the economy reform, and especially since 1990s, as institutional barriers deterring labor mobility have gradually eliminated, more rural laborers move to cities for employment. Migrant workers usually work in informal sectors or engage in self-employment. Compared with urban locals, migrant populations have lower income and consumption levels, worse living conditions and lower coverage rates of social insurance programs. Additionally, they do not have equal access to children's education, social welfare benefits and public services as compared with urban residents.

For migrants, they usually do not have much asset income and transfer income. There are a variety of factors that contribute to instability in the lives of the working poor. Labor income is usually their most important income source. When they lose their job due to old age, suffering from economic crisis or other reasons, they are very likely to fall into poverty. Since they are not well covered by social security, they do not have stable expectations for their future and also have low consumption levels. Most migrant workers live in dormitories, working sites or rented houses and only a very small portion of them have their own houses. Their living conditions are usually not satisfactory. Most migrants are not covered by medical insurance programs and they are very likely to fall into poverty if they or their family members fall ill. Some children of migrant workers live with their parents in the city and some are left behind in the rural hometowns. Migrant children and 'left-behind' children usually receive worse education than urban children, which affects their future employment and income and consequently, causes intergenerational transmission of poverty.

Migrant poverty has become an important component of urban poverty in the process of urbanization. The minimum living standard guarantee program beginning from 2007 (hereafter referred to as "dibao" program) is the most important public assistance program for poverty in China. However, poor migrant populations are not eligible to apply for urban "dibao". Due to complicated application procedures, it is almost impossible for migrant populations to apply for rural "dibao" in their home provinces. Therefore, migrant populations are actually excluded from the "dibao" program that is meant to assist people living in poverty. With the rapidly increasing number of migrants, more attention and analysis should be given to this population, and to the public assistance policies. This study analyzes the situation of poor migrant populations in cities and reveals the factors and challenges associated with poverty alleviation. Based on the analysis, policy recommendations will be presented.

2. Labor Migration from Rural to Urban Areas

The implementation of the rural household responsibility system initiated in late 1970s has released a great number of surplus laborers from agriculture. The higher returns in non-agricultural sectors motivated farmers to leave the agricultural industry. The migration of rural surplus laborers has several phases. The first phase was migrating from agriculture to forestry, animal husbandry and fishery industries. The second was migrating to township and village enterprises. The last was migrating among regions and to urban areas.

The gradual abolition of institutional obstacles has been the key to motivating labor mobility among regions. Since the 1980s, the government has gradually eliminated the policies which deterred the mobility of rural surplus laborers. In 1983, the government began allowing farmers to engage in long distance transport and marketing of their products beyond local market places, which was the first time that Chinese farmers had legitimate rights of doing business outside their hometowns. In 1984, regulations were further relaxed and farmers were encouraged to go to nearby small towns to work. A major policy reform took place in 1988, when the central government allowed farmers to work in enterprises and/or run their own businesses in cities under the condition of self-sufficient foods.

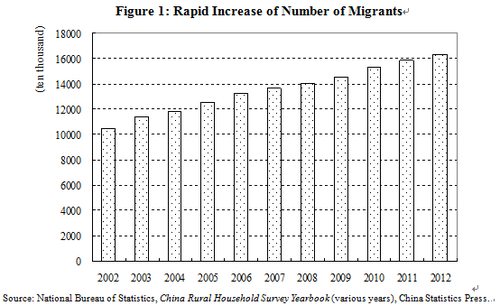

The gradual reforms of the urban employment system, social security system and social welfare system since the 1980s have further created institutional environments for rural to urban migration. The labor demand created by the development of the non-state-owned economy, the reform of the food rationing system and the reform of the housing allocation policy, medical system and employment system all reduced farmers' cost of migrating to cities for employment. As a result of these institutional reforms and policy adjustments, the number of rural to urban migrants has rapidly increased. In 2002, the total number of migrants had just exceeded 100 million[1]. It reached 163 million in 2012, increasing by 56 percent in ten years (Figure 1). 10 percent of migrants work in municipalities, 20.1 percent in provincial capitals, 34.9 percent in prefecture-level cities, 23.6 percent in county-level cities, and the rest (11.4 percent) in small towns.

Due to the increased of number of migrants, the migration pattern of farmers has been changing. In recent decades, agriculture has been the main industry of rural surplus laborers. When the employment situation in cities worsens, some migrants go back to their rural provinces. When the employment situation in cities gets better, some of them return to cities (Cai et al., 2003). There is both outflow and reflux in farmers' mobility. In 2008, migrants suffered from the financial crisis with some losing their jobs and returning home. However, many returned to the cities after a short stay through the Chinese holidays in the winter of 2008-09. This indicates that migration pattern of farmers has changed from one with both outflow and reflux to one with only leaving rural areas and agriculture to cities and non-agricultural sectors (Wang, 2011). Migrants become a very large and important group in China's urban labor market.

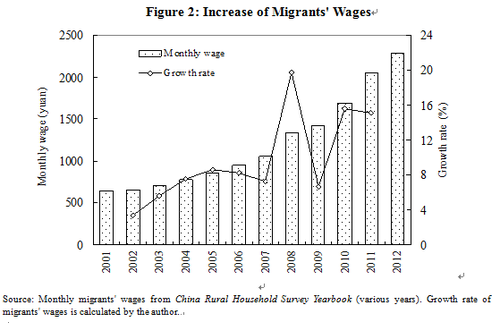

Besides the increased number of migrants and new migration patterns, the wages of migrants has been increasing rapidly. Throughout the 1990s, migrants' wages had stagnated. The rapid increase of migrants' wage in recent years is an inevitable result of labor shortages with the coming of Lewis turning point (Cai, 2008). The annual growth rate of migrants' wage was 3.4 percent in 2002 and it increased to 8.6 percent in 2005 and 19.7 percent in 2008. There was a fall in the growth rate of migrants' wage in 2009. In 2010 and 2011, migrants' wage kept a strong growth and the annual growth rates have both exceeded 15 percent in these two years (Figure 2).

Despite the rapid increase in wages, it cannot be ignored that migrants' wages are still relatively low. In 2012, the average monthly wage of migrants was only 2290 yuan. This income is not only used to support individuals, but also family members. It is inevitable that some migrant workers and their family members are living in poverty. Income poverty is only one aspect of migrants' poverty. In addition to income, people living in poverty also need improved education, health care and living conditions (Sen, 1985, 1999). Therefore, poverty of migrant populations must be examined from multiple dimensions. This report analyzes migrants' poverty from several perspectives including focuses on income, consumption levels, living conditions, social security and education. We will compare the lives of urban migrants with that of urban residents in order to show a clearer picture and comparison of urban poverty.

3. Poverty of Migrant Population

As previously mentioned, migrants' income is still low, which causes some migrants to fall into poverty. Additionally, migrants are not well covered by social security and do not have stable expectations for their future, which leads to low consumption levels. Most migrant workers do not have their own houses in cities and their living conditions are not satisfactory. Some migrants bring their children to cities and some migrants leave their children behind in rural hometowns. Both migrant children and 'left-behind' children generally do not receive very good education. Additionally, due to the "hukou" (local resident registration system), migrants cannot access to equal social welfares and public services as urban residents.

1) Income Poverty of Migrant Population

Although there is no poverty line in urban areas, there is consensus on the definition of poor households and poor population that households whose household income per capita is below poverty line are deemed poor households and all household members in poor households are deemed poor population. Obviously, a poverty line is basic indicator to measure poverty. There are various methods to measure poverty and each method has its own advantages and disadvantages. Basically, the methods can be divided into two categories: 1) absolute standard method; 2) relative standard method respectively. The absolute standard method refers to the inadequate basic expenditure on clothing, food, housing and transportation, etc. as poverty line to measure poverty. The relative standard method refers to: (1) sorting the population by income and taking a fixed proportion of population at the bottom as the poor population; or (2) taking half of the median (or mean) income as the poverty line (Wang, 2003).

Among absolute standard methods, 1 US dollar or 1.5 US dollars per day is a representative poverty line and widely adopted by many low-income countries (Ravallion and Van de Walle, 1991). However, this standard is not an ideal standard. Firstly, it ignores price changes among different regions and different time periods within a country. Secondly, it relies on Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) to measure the living cost of a region, which also causes some problems (Ravallion and Chen, 1997). Some studies use official poverty lines to measure poverty (Newman and Struyk, 1983). Some other studies use the relative standard, for example, to take households whose income per capita below half of median incomes of all households and label that total as poor households (Casper, McLanahan and Garfinkel, 1994).

There is an official rural poverty line in China, but no urban poverty line. When analyzing urban poverty, many studies adopt urban "dibao" standards as the poverty line. Urban "dibao" standard is determined according to the local living expenditure on clothing, food, housing, water, electricity, gas, etc. This study will take urban "dibao" standard as the poverty line (poverty line 1) to calculate poverty rate (poverty rate 1). Since the urban "dibao" standard is relatively low, this report will also use 1.5 times urban "dibao" standard as a poverty line (poverty line2) to calculate poverty rate (poverty rate 2). The data used is from the China Urban Labor Survey data from 2010[2].

Table 1 shows that, both poverty rate 1 and poverty rate 2 of migrant populations are lower than those of urban residents. The poverty rate 1 of the migrant population is lower by 1 percentage point than that of urban residents and the poverty rate 2 of the migrant population is lower by about 2 percentage points than that of urban residents. However, there exist some differences among different cities. The poverty rate of migrant populations is higher than that of urban residents in Shanghai and Fuzhou and it is lower than that of urban residents in the other cities. Overall, there is no significant difference in poverty rates between migrant population and urban residents.

Table 1: Poverty Line and Poverty Rates of Migrant Population and

Urban Residents

|

City |

Urban "dibao" standard (poverty line 1) yuan/year |

1.5 times Urban "dibao" standard (poverty line 2) yuan/year |

Poverty rate 1 |

Poverty rate 2 |

||

|

|

|

|

Migrant population |

Urban residents |

Migrant population |

Urban residents |

|

Shanghai |

5100 |

7650 |

3.84 |

2.88 |

7.34 |

4.92 |

|

Wuhan |

3288 |

4932 |

2.10 |

3.43 |

2.96 |

7.73 |

|

Shenyang |

3936 |

5904 |

5.35 |

6.94 |

11.21 |

13.62 |

|

Fuzhou |

2700 |

4050 |

9.49 |

6.95 |

10.49 |

9.40 |

|

Xi'an |

2760 |

4140 |

3.28 |

4.96 |

8.64 |

8.86 |

|

Guangzhou |

4788 |

7182 |

1.57 |

5.08 |

4.04 |

9.69 |

|

Total |

--- |

--- |

3.99 |

5.02 |

7.07 |

9.01 |

Note: Urban "dibao" standard here is an annual standard, which is equal to urban "dibao" standard in the first quarter of 2010 multiplied by 12.

Source: Author's calculation based on China Urban Labor Survey data in 2010.

Another study also finds that there is not a large difference in poverty rates between migrant population and urban residents (Park and Wang, 2010). Generally speaking, people tend to think that the income of migrants is lower than that of urban residents and therefore their poverty rate should be higher. This report's conclusion differs from that idea. When examining the income and household size of migrant households and urban households together in detail, this difference is clear. The average annual income of migrant households is 44217 yuan and that of urban households is 61536 yuan. The annual income of migrant households is 72 percent of that of urban households (Table 2). However, since the average size of migrant households (2.27 people) is smaller than that of urban households (2.89 people), the average annual income per capita of migrant households reaches 91 percent of that of urban households.

Table 2 Income and Its Components of Migrant Households and Urban Households

|

|

Annual income |

Annual income per capita |

||||

|

|

Migrant Households (yuan)(MT) |

Urban Households (yuan) (UT) |

MT/UT |

Migrant Households (yuan) (MA) |

Urban Households (yuan) (UA) |

MA/UA |

|

Labor income |

42139 |

39704 |

1.06 |

18539 |

13754 |

1.35 |

|

Property income |

417 |

3431 |

0.12 |

183 |

1189 |

0.15 |

|

Transfer income |

1661 |

18401 |

0.09 |

731 |

6374 |

0.11 |

|

Total |

44217 |

61536 |

0.72 |

19453 |

21317 |

0.91 |

Note: Income is calculated according to the statistics standard of urban household survey by National Bureau of Statistics. Wage income and business income is combined together into labor income. Transfer income does not include urban ‘‘dibao’' income and other subsidies.

Source: Author's calculation based on China Urban Labor Survey data in 2010.

However, it is important to note that the size of migrant households here only includes family members who live in cities for more than 6 months. For migrants, some of their family members do not come to cities, but rather stay in the rural areas, or travel back and forth. According to China Urban Labor Survey data in 2010, for married migrants, 11 percent of them do not bring their spouses to cities. One third of migrant households leave their children in countryside. The income of migrants is not only to support their family members in cities, but also to send to their other family members in rural areas. Therefore, the poverty rate of migrants is underestimated in some degree when only their family members in cities are taken into consideration.

Furthermore, migrants are very likely to fall into poverty when they lose their labor income due to their income structure. For migrants, labor income is their main income source (over 95 percent) and they do not have hardly any property income or transfer income. The summation of annual property income and transfer income per capita is only a little more than 900 yuan. When they lose their jobs due to illness or other reasons, they will lose their labor income and are very likely to fall into poverty. Meanwhile, for urban residents, the proportion of labor income in the total income is only 65 percent. Their annual property income and transfer income per capita is over 8000 yuan. Even if they lose their labor income, their property income and transfer income can be used to support their living expenditures.

2) Multi-dimensional Poverty of Migrant Population

Firstly, it is important to discuss the details of the living expenditure of migrant populations. The annual living expenditure per capita is 12530 yuan for migrant populations and 12683 yuan for urban residents (Table 3). It seems that there is no difference between these two groups. However, if we look at the detailed categories of the living expenditures, most categories for migrant populations are lower than those for urban residents and some categories are significantly lower. For instance, the annual expenditure per capita on household equipments and maintenance for migrant population is only 150 yuan, which is only 38 percent of that for urban residents (399 yuan). The expenditures on health for migrant population is only 43 percent of that for urban residents and the expenditure on culture and recreation for migrant population is only 42 percent of that for urban residents.

Table 3: Living Expenditure Per Capita of Migrant Population and Urban Residents (yuan/year)

|

|

Migrant population (1) |

Urban residents (2) |

(1)-(2) |

(1)/(2) |

|

Food |

4626 |

5401 |

-775 |

0.86 |

|

Clothing |

910 |

1048 |

-138 |

0.87 |

|

Housing |

3605 |

1245 |

2360 |

2.90 |

|

Household equipments and maintenance |

150 |

399 |

-249 |

0.38 |

|

Health |

347 |

808 |

-461 |

0.43 |

|

Communication and transportation |

1559 |

1715 |

-156 |

0.91 |

|

Education |

673 |

956 |

-283 |

0.70 |

|

Culture and recreation |

261 |

620 |

-359 |

0.42 |

|

Other items |

399 |

491 |

-92 |

0.81 |

|

Total |

12530 |

12683 |

-153 |

0.99 |

Source: Author's calculation based on China Urban Labor Survey data in 2010.

The only exception is, the annual expenditure per capita on housing for migrant population is much higher, which is 2.9 times that for urban residents. If we deduct housing expenditure from the total living expenditure, the rest of the living expenditures per capita for migrant populations is 8925 yuan, which is only 78 percent of that for urban residents (11438 yuan).

Why is the housing expenditure for migrant populations that much higher than that for urban residents? The housing expenditure refers to costs for rented homes, water, electricity, gas, heating, etc. According to the China Urban Labor Survey in 2010, 67 percent of migrants live in rented houses, 20 percent live in working sites and the rest migrants live in dormitories, own their houses or other places. However, for urban residents, 82 percent own their own houses and only a very small portion of them rent houses. For migrant populations, the annual expenditure per capita for renting houses is 2845 yuan, which accounts for 80 percent of their total housing expenditure and one fourth of their total living expenditure. The annual expenditure per capita on renting houses for urban residents is only 265 yuan.

Monitoring surveys on migrant workers by the National Bureau of Statistics also shows very similar results (See Table 4). Among migrant workers, one third of them live in rented houses, one third live in dormitories and about 16 percent live at working sites. A small portion of migrant workers live in their own houses in cities or live in houses in their hometowns. For migrants who rent houses, the expenditure for renting houses becomes an important component of their total living costs.

Table 4: Living Places of Migrant Workers (%)

|

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Rented houses |

35.5 |

34.6 |

34.0 |

33.6 |

33.2 |

|

Working sites |

16.8 |

17.9 |

18.2 |

16.1 |

16.5 |

|

Dormitories |

35.1 |

33.9 |

33.8 |

32.4 |

32.3 |

|

Own houses |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

|

Houses in hometowns |

8.5 |

9.3 |

9.6 |

13.2 |

13.8 |

|

Other places |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

4.0 |

3.6 |

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, China Rural Household Survey Yearbook (various years), China Statistics Press.

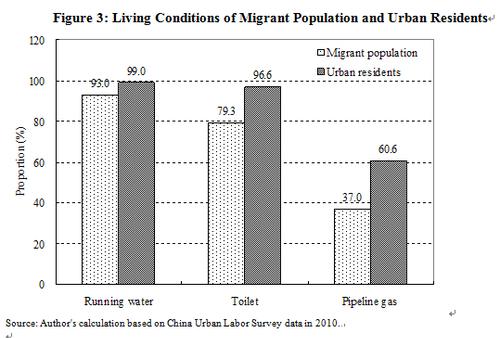

Compared with urban residents, the living conditions of migrant populations are worse. According to China Urban Labor Survey in 2010, 93 percent of living places for migrants have running water and 79 percent have toilets. However, almost all living places for urban residents have running water and toilets. In addition, only 37 percent of living places for migrants have pipeline gas and this proportion for urban residents is over 60 percent (Figure 3).

Migrant populations are not been well covered by social insurance programs, which is another reflection of their poverty. Many studies show that, social security can promote consumption levels (Feldstein, 1974;Munnell, 1974;Zhang, 2008). Due to a lack of social security, migrant populations do not have stable expectations for their future, which then affects their consumption behaviors. According to China Urban Labor Survey in 2010, the coverage rates of urban basic pension insurance, urban basic medical insurance, unemployment insurance and work injury insurance for migrant populations are all below ten percent, which are much lower than those for urban residents (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The Coverage of Social Insurance Programs for Migrant Population and Urban Residents

Source: Author's calculation based on China Urban Labor Survey data in 2010.

Table 5: Coverage Rates of Social Insurance Programs for Migrant Workers (%)

|

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Pension insurance |

9.8 |

7.6 |

9.5 |

13.9 |

14.3 |

|

Medical insurance |

13.1 |

12.2 |

14.3 |

16.7 |

16.9 |

|

Unemployment insurance |

3.7 |

3.9 |

4.9 |

8.0 |

8.4 |

|

Work injury insurance |

24.1 |

21.8 |

24.1 |

23.6 |

24.0 |

|

Maternity insurance |

2.0 |

2.4 |

2.9 |

5.6 |

6.1 |

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, China Rural Household Survey Yearbook (various years), China Statistics Press.

According to monitoring surveys on migrant workers by the National Bureau of Statistics, we can also see that the proportions of participating in social insurance programs for migrants are low (Table 5). The coverage rate of work injury insurance for migrants is about one fourth of migrant workers, which is the highest among all insurance programs. However, the coverage rate of work injury insurance has not changed in recent years. The coverage rates of pension insurance, medical insurance, unemployment insurance and maternity insurance for migrants are relatively low, but all these coverage rates have shown an increasing trend.

Special attention should be paid to the education of migrants' children. A person's education directly affects his/her employment and income opportunities in the future. If migrants' children cannot receive quality education, it will cause intergenerational transmission of poverty. As previously mentioned, some migrants bring their children to cities and some leave their children behind in rural areas. Migrant workers' children are entitled to go to public schools in cities for free according to the local policies in most cities. However, in reality, migrants have to pay extra money for the education of their children in public schools. Therefore, many migrants have to send their children to migrant schools, which are not publicly funded and typically are of lower standard and quality. A survey in Beijing shows that 61.4 percent of migrant children are in migrant schools, 30.8 percent are in public schools and 6.5 percent are in private schools (Gao, 2009).

There exists some gap on enrollment rates between migrant children in cities and urban children (Table 6). For children aged 6-11 and aged 12-14, the gap is not large[3]. However, for children aged 15-17, enrollment rate of migrant children is much lower than that of urban children. The significant gap indicates that a large proportion of migrant children quit school after they finish compulsory education (for 9 years) and most of urban children continue receiving education after compulsory education, continuing to complete secondary school.

Table 6: Enrollment Rates of Migrant Children and Urban Children (%)

|

|

6-11 years |

12-14 years |

15-17 years |

|||

|

|

Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

|

Migrant Children |

95.7 |

95.4 |

94.4 |

94.2 |

46.3 |

36.6 |

|

Urban Children |

96.4 |

96.6 |

96.6 |

96.3 |

82.3 |

82.8 |

Source: Gao, 2009.

Another important issue of migrant children' education is that they cannot attend college entrance examinations in cities where they receive education; they can only participant in the examinations in their hometowns. That is one of the reasons why many migrants have to leave their children in their hometowns. For migrants who bring their children to cities, they are worried a lot about when and how to send their children back to their hometowns in order to attend college entrance examinations.

There are also significant issues for children who do not accompany their parents to cities. 'Left-behind' children in rural areas lack their parents' care, which will affect their education and health. For 'left-behind' children aged 0-5 years, 6-11 years and 12-14 years, more than half of them belong to the group whose parents are both absent and the rest of them belong to the group whose mother or father are absent (Table 7). For 'left-behind' children aged 15-17 years in rural areas, 42 percent of them belong to the group whose parents are both absent and 58 percent of them belong to the group whose mother or father are absent. Left-behind children in rural areas usually live with their grandparents and their parents do not have much time to go back to hometowns to visit them.

Table 7: Living Arrangement of Left-behind Children in Rural Areas (%)

|

Age group |

0-5 years |

6-11 years |

12-14 years |

15-17 years |

|

Mother or father are absent |

44.70 |

42.37 |

49.56 |

57.63 |

|

Parents are both absent |

55.30 |

57.63 |

50.44 |

42.37 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: ACWF, 2008.

Additionally, 'left-behind' children receive their education in rural areas with lower quality schools and teachers. The gap between teachers' quality in rural and urban areas reflect the education quality gap. One indicator that can measure teachers' quality is the educational level of teachers. In urban areas, only 4.77 percent of teachers are junior secondary school and below and 18.09 percent are senior secondary school. In rural areas, these two proportions are 12.95 percent and 42.76 percent respectively. In urban areas, 42.1 percent of teachers are tertiary technical school and 35.04 percent of teachers are tertiary academic institution and above. In rural areas, only 38.51 percent of teachers are tertiary technical school and 5.77 percent of teachers are tertiary academic institution and above[4].

The household registration system has been reformed in many aspects in recent years. However, no substantive progress has been made so far to make important improvements. Due to no urban local "hukou", migrant population cannot have equal access to social welfare benefits and public services as compared with urban residents. For instance, since migrants are not covered by urban governments' employment assistance policies and social protection, they will be in a difficult situation when they suffer from unexpected employment. A good example is the case of many migrant workers losing their jobs during the financial crisis in 2008 and returning to their hometowns as a result of sudden unemployment.

4. The Assistance of the "dibao" Program to Poor Migrant Populations

The "dibao" program is currently the main poverty assistance program in China, which includes urban "dibao" and rural "dibao" programs. In 1993, Shanghai established the urban "dibao" program, which marked the start of China's traditional social assistance system reform. From 1993 to 1999, some coastal cities in eastern regions established urban "dibao" programs. In 1999, urban "dibao" programs were established all over China. For rural "dibao" programs, the pilots in some regions began in 1993 and were finally established all over China in 2007.

According to the regulations of the "dibao" program, rural and urban residents who meet the criteria are entitled to apply for "dibao" with township governments (or urban neighborhood offices) in his or her place of "hukou" (residential certificate in place of birth) registration. The township governments (or urban neighborhood offices) will investigate and verify the information on the application. Then the resident representatives or the community will review the application and submit the application to the Civil Affairs Bureau at the county level. When the Civil Affairs Bureau at the county level approves the application, the names of applicants and the approval decisions will be posted in the place of "hukou" registration. For migrants, their places of "hukou" registration are in rural areas and their places of residence are in urban areas. Based on the complicated procedure of applying for "dibao", it is very difficult for migrants to apply for rural "dibao". Meanwhile, migrants are also not eligible to apply for urban "dibao". This means that, migrants are actually excluded from "dibao" programs entirely. Besides the "dibao" program, many other kinds of assistance programs such as medical assistance programs, and education assistance programs are also difficult for migrants to apply for as a result of the same circumstances and regulations.

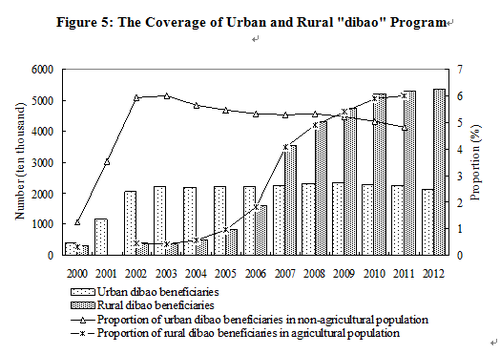

Additionally, the coverage rates of both urban and rural "dibao" programs are relatively low (Figure 5). The number of urban "dibao" beneficiaries was 4.03 million in 2000 followed by a rapid increase in the following two years. It stayed at about 22 million since 2003. It had a small increase in 2008, reaching 23.35 million. And it further increased to 23.46 million in 2009. Since then, the number of urban "dibao" beneficiaries started to decline and it was 21.44 million in 2012. The proportion of urban "dibao" beneficiaries in non-agricultural populations rose from 2000 to 2002 and it reached the peak (6 percent) in 2003. The proportion started to decline afterwards.

Both the number and proportion of rural "dibao" beneficiaries in agricultural populations have increased rapidly in recent years. There was a significant increase on both the number and the proportion in 2007. This is because the rural "dibao" program became well-established all over China that year. However, compared with the huge number of agricultural populations, the number of rural "dibao" beneficiaries is still relatively low considering the total population. It was 53.45 million and its proportion in agricultural population was 5.99 percent in 2012.

For both urban and rural "dibao", the standard and subsidy level and their growth rates are low. The average standard per month of urban "dibao" in 2003 was 149 yuan. And it only increased to 330 yuan in 2012. The average subsidy level per month of urban "dibao" was 58 yuan in 2003 and it only reached 239 yuan in 2012. The average standard and subsidy level of urban "dibao" grew by about 20 yuan annually. The standard and subsidy level of rural "dibao" were even lower and they were only 172 yuan and 104 yuan per month respectively in 2012 (Table 8).

Table 8 Standard and Subsidy Level of Urban and Rural "dibao" (yuan/per month)

|

Year |

Urban "dibao" |

Rural "dibao" |

||

|

|

"dibao" standard |

Subsidy level |

"dibao" standard |

Subsidy level |

|

2003 |

149 |

58 |

--- |

--- |

|

2004 |

152 |

65 |

--- |

--- |

|

2005 |

156 |

72 |

--- |

--- |

|

2006 |

170 |

84 |

--- |

--- |

|

2007 |

182 |

103 |

70 |

39 |

|

2008 |

205 |

144 |

82 |

50 |

|

2009 |

228 |

172 |

101 |

68 |

|

2010 |

251 |

189 |

117 |

74 |

|

2011 |

288 |

240 |

143 |

106 |

|

2012 |

330 |

239 |

172 |

104 |

Source: Ministry of Civil Affairs, The Statistical Report on the Development of Civil Affairs (various years), downloaded from the website of Ministry of Civil Affairs http://cws.mca.gov.cn/article/tjbg/.

By the regulations on the "dibao" program, "dibao" standards are determined according to residents' expenditure on clothing, food, housing, etc. The average monthly food expenditure for urban residents and rural residents was 503 yuan and 194 yuan respectively in 2012. Urban "dibao" standard was only 66 percent of urban residents' food expenditure and rural "dibao" standard was only 89 percent of rural residents' food expenditure. Both urban and rural "dibao" standard are not enough for food expenditure. The average disposal income per capita of urban residents and the average net income per capita of rural residents were 2047 yuan and 660 yuan respectively in 2012. If we regard "dibao" standard as the average income per capita of "dibao" beneficiary, urban "dibao" standard was only 16 percent of the average disposal income per capita of urban residents and rural "dibao" standard was only 26 percent of the average net income per capita of rural residents.

If migrant populations were excluded from "dibao" program for a long period of time, it would be unfair for them. And it would also cause many social problems. Deciding how to include migrant population in the coverage of "dibao" program is an important task for the government. In addition, the standard and subsidy level of the "dibao" program are still very low. Even if migrant population were covered by the program, the role of the "dibao" program on poverty reduction would be limited. Deciding how to increase the financial input, expand the coverage and improve the standard and subsidy level of "dibao" programs is another challenge governments are faced with.

5. Other Ways to Alleviate the Poverty of Migrant Populations

Poverty alleviation usually includes two aspects: the first is to provide the poor with public assistance and the second is to prevent others populations from falling into poverty. In the previous sections, the report discussed how to provide the assistance to poor migrant population. In this section, two possible ways to prevent migrant population from falling into poverty will be examined. The first way is to help them improve their human capital, employment and income. The second is to further expand household registration system reform to give migrant populations equal access to social welfare benefits and public services as urban residents.

Human capital is a determining factor in employment and income, and focusing on improving in these areas is an effective way to prevent migrant populations from falling into poverty. The improvement of human capital mainly relies on education and training. For migrant populations in cities, it is almost impossible for them to receive more formal education, so the best way to assist them is to provide training. The training programs by private agencies are usually too expensive for migrant workers. Employers do not have much incentive to provide training for migrant workers because migrant workers tend to change their jobs frequently. The government should give much more attention to migrant workers' training and skill development.

Migrant children in cities and 'left-behind' children in rural areas will be the future migrant populations. They should receive more and better education to prevent intergenerational transmission of poverty. Since they don't have urban local "hukou", migrant children are in a disadvantaged position in receiving education in cities. The central and local government should give more attention to their education. Since 'left-behind children receive education in rural areas, both the central government and local governments should increase financial payment on education and make great efforts to improve educational quality in rural areas. In addition, some school-age children drop out of school very early due to poverty. Assistance should be provided to prevent them from dropping.

The fundamental way to provide migrant population with equal access to social welfare benefits and public services as urban residents is to implement a thorough household registration system. The central government and local governments have implemented various kinds of household registration system reforms in the past decades, however, these systems still function as an "invisible wall" that defines the different identities of urban populations and migrant populations and treats migrant populations differently. Further, reforms on household registration system should be implemented as soon as possible in the upcoming years.

References:

All-China Women Federation (ACWF) (2008), "A Report on Rural Left-behind Children in China", Unpublished.

Cai, Fang (2008), Lewis Turning Point: A Coming New Stage of China's Economic Development, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Cai, Fang, Yang Du and Meiyan Wang (2003), The Political Economy of Labor Migration, Shanghai: Shanghai Sanlian Bookstore, Shanghai People's Publishing House.

Cai, Fang, Yang Du and Meiyan Wang (2005), How Close is China to a Labor Market? Beijing: The Commercial Press.

Casper, Lynne M., Sara S. McLanahan and Irwin Garfinkel (1994), "The Gender-Poverty Gap: What We Can Learn from Other Countries", American Sociological Review, Vol.59, No.4, pp.594-605.

Feldstein (1974), "Social Security, Induced Retirement and Aggregate Capital Accumulation", Journal of Political Economy, Vol.82, No.5, pp.905-926.

Gao, Wenshu (2009), "Education of Left-behind Children and Migrant Children", in Fang Cai (eds) Reports on China's Population and Labor No.10, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Khan, Aziz, Keith Griffin and Carl Riskin (2001), "Income Distribution in Urban China during the Period of Economic Reform and Globalisation", in Carl Riskin, Renwei Zhao and Shi Li (eds) China's Retreat from Equality: Income Distribution and Economic Transition, New York, M.E. Sharpe.

Munnell (1974), The Effect of Social Security on Personal Saving, Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger.

Newman, J. Sandra and Raymond J.Struyk (1983), "Housing and Poverty", The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol.65, No.2, pp.243-253.

Park, Albert and Dewen Wang (2010), "Migration and Urban Poverty and Inequality in China", IZA Discussion Paper No.4877.

Ravallion, M. and Chen, S. (1997), "What Can New Survey Data Tell Us About Recent Changes in Distribution and Poverty?" World Bank Economic Review, Vol.11, No.2, pp.357-382.

Ravallion, M., Datt, G., and van de Walle, D. (1991), "Quantifying Absolute Poverty in the Developing World ", Review of Income and Wealth, Vol.37, No.4, pp.345-361.

Riskin, Carl and Shi Li (2001), "Chinese Rural Poverty Inside and Outside the Poor Regions", in Carl Riskin, Renwei Zhao and Shi Li (eds) China's Retreat from Equality: Income Distribution and Economic Transition, New York, M.E. Sharpe.

Sen, Amartya (1985), Commodities and Capabilities, New York: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya (1999), Development as Freedom, New York: Oxford University Press.

Wang, Meiyan (2011), "Can Migrant Workers Go Back to Agriculture?----An Analysis Based on National Farm Product Cost-benefit Survey", China Rural Survey, No.1.

Wang, Xiaolin (2012), The Measurement of Poverty: Theories and Methods, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Wang, Youjuan (2003), "Measuring Urban Poverty in China", in Fang Cai (eds) Reports on China's Population and Labor No.4, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Zhang, Jihai (2008), The Impacts of Social Security on Urban Residents' Consumption and Saving Behavior in China, Beijing: China Social Sciences Press.

[1] Here 'migrants' refers to rural laborers who migrate beyond their own townships and work for more than 6 months.

[2] China Urban Labor Survey in 2010 was conducted in Shanghai, Wuhan, Shenyang, Fuzhou, Xian and Guangzhou by Institute of Population and Labor Economics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. A proportional population sampling approach was used to sample 700 urban households in each city. Each household head was asked questions about the household, and then all household members were interviewed individually. We also interviewed 600 migrant households in each city.

[3] China implements nine-year compulsory education (primary education and junior high education). Children usually start school at 6 years old. Therefore, 6-11 years and 12-14 years are usually the periods to receive compulsory education.

[4] Calculated from 20 percent sample of micro data of 1 percent population sampling survey in 2005.

扫描下载手机客户端

地址:北京朝阳区太阳宫北街1号 邮编100028 电话:+86-10-84419655 传真:+86-10-84419658(电子地图)

版权所有©中国国际扶贫中心 未经许可不得复制 京ICP备2020039194号-2