2012-China-ASEAN Forum Report1

The 6th China-ASEAN Forum on Social Development and Poverty Reduction

Inclusive Development and

Poverty Reduction

International Poverty Reduction Center in China

September 26-27 2012, Liuzhou China

Editor‘s Note

During years 2007-2011, we have successfully held five China-ASEAN Forums respectively in China, Vietnam and Indonesia. Nearly one thousand people participated in the Forums, including government officials, experts and other representatives from China, 10 ASEAN countries, ASEAN secretariat and international organizations. The Forums shared the successful experiences of China in poverty reduction, strengthen the exchanges and cooperation among ASEAN countries in poverty reduction and social development, deepened mutual understanding and friendship and made contributions to diplomatic relations with neighbouring countries. Currently, the forum mechanism has been established and the forum is held in China and ASEAN countries by turns. The conference mode of "in-depth discussions on the theme and field visits based on actual situation" has been gradually established and accepted by the participants. This year is the Sixth China-ASEAN Forum on Social Development and Poverty Reduction. After extensive discussion, "Inclusive Development and Poverty Reduction" is finally selected as the theme of the Forum which includes six aspects: narrowing development gap and poverty reduction; industrial and technology transfer and poverty reduction; trade facilitation and poverty reduction; social protection and poverty reduction; poverty reduction in urbanization process; poverty issues of special groups. Based on the forum topic, we invite experts to write this thematic report.

Special thanks will be given to United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific (UNESCAP), as well as the authors of the thematic report: Dr. Tang Min, Prof. Wu Laping, Dr. Kornkarun Cheewatrakoolpong, Dr. Sothitorn Mallikamas, Mr. Tulus T. H. Tambunan, Mr. Peter Chaudhry, Dr. Wang Xiaolin and Dr. Liu Qianqian. We would also like to thank UNDP China Country Director Mr. Christophe Bahuet, Assistant Country Director Ms. Hou Xin’an, programme officers Ms. Pei Hongye and Ms. Zhang Yan, Dr. Zhang Deliang and Dr. Li Linyi from IPRCC for their contribution to this report.

China-ASEAN Relations in the context of Inclusive Development

Qianqian LIU, Xiaolin Wang

International Poverty Reduction Center in China

[Abstract] Growth, poverty and inequality are three major challenges faced by China and ASEAN countries. Governments of China and Southeast Asian countries attach great importance to inclusive development and poverty reduction. Inclusive development implies that everyone should be involved in the process of development and share the achievements of development. In the international level, it also requires the inclusiveness of international relations between China and ASEAN, which, in particular, has political, economic and cultural meanings. Strengthening cooperation between China and ASEAN countries on inclusive development and poverty reduction helps build mutual trust between China and ASEAN countries, and therefore offers a breakthrough for China-ASEAN relations in general.

[Key words] Inclusive Development; Poverty Reduction; China-ASEAN Relations

1. Introduction

Since 1991, China and ASEAN have been working closely on economic, political, and cultural aspects. Within the framework of the Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity, China and ASEAN countries have gradually improved their relations. However, with the outbreak of 2008 global financial crisis and the America’s ‘return to Asia’, China-ASEAN relationship has been confronted with many new challenges. Stable economic growth and successful poverty reduction are common concerns of China and ASEAN countries. Promoting inclusive development between the two sides could be a key policy lever to further China-ASEAN strategic partnership.

During the past couple of decades, China and ASEAN countries reduced the proportions of populations in poverty through promoting economic growth. However, the poverty reduction process in these countries is imbalanced. Some countries have great achievements whereas others are plagued by poverty and inequality. Continuous economic growth and equal development opportunities are the basic requirements to improve the quality of life comprehensively. In recent years, governments of China and other ASEAN countries have attached great importance to the strategy of inclusive growth and development.

Economic growth is aimed at boosting social development. Growth, poverty and inequality are interconnected. Impact of growth on poverty alleviation was known as "trickle-down effect" and later "pro-poor growth" and "inclusive growth". So far "inclusive development" has been given more weight. In its "12th Five Year Development Plan", China highlights the transformation of its development pattern, which indicates a more inclusive domestic development strategy and foreign relations. Promoting inclusive development between China and ASEAN countries and accelerating regional poverty reduction and sustainable development through China-ASEAN Social Development and Poverty Reduction Forum are of great significance to a sound China-ASEAN strategic partnership for peace and prosperity.

In the second section, this paper discusses inclusive development from the perspective of international relations. In the third section, it analyzes the current situation of growth, poverty and inequality in China and ASEAN countries. In the fourth section, it gives a review and analysis of challenges in China-ASEAN relations. In the fifth section, several policy suggestions are given regarding China-ASEAN relations against the backdrop of inclusive development and poverty reduction.

2. Inclusive Development from the Perspective of International Relations

2.1. Definitions of Inclusive Growth and Inclusive Development

The concept of inclusive growth was based on ever deepening understanding of poverty. Classical economists believe that economic growth would ultimately benefit poor populations through "trickle-down effect" and it is the main driver for poverty reduction (Deininger and Squire, 1997; Dollar and Kraay, 2002; White and Anderson, 2001; Ravallion, 2001; Bourguignon, 2003). However, empirical studies show that not all economic growth can contribute to poverty reduction. Only when economic growth sustains and brings benefits to all people, can extensive poverty reduction be achieved. Bourguignon (2003) puts forward the triangle of "poverty-economic growth-income distribution", arguing that besides growth effect, income distribution is important to influence economic growth‘s role in poverty reduction. Kakwani and Pernia (2000) came up with the concept of pro-poor growth in their paper of What is Pro-Poor Growth for the measurement of growth benefits to poor populations. Ravallion and Chen (2003) proposed the pro-poor growth index. Kakwani, Khandker and Son adopted "poverty equivalent growth rate (PEGR)" to assess pro-poor growth.

Amartya Sen (1983) recognizes that traditional development economics give more priority to the growth of national output, gross income and total supply while neglecting "entitlement" and "capability". He believes that economic growth is only a means while development is the real goal. Development can be seen as a process of expanding the real freedoms that people enjoy and as expansion of entitlements. Poverty of entitlements is what limiting people‘s access to freedoms. To shake off poverty, equal entitlements and freedoms of all should be ensured. He advocates that social security should be improved by empowering people with economic freedoms and social opportunities. Therefore, according to his definitions of "entitlement" and "capability", only when entitlement to and capability of human development are secured can we realize inclusive growth and development.

The attention shift from GDP growth to income distribution is only the first step towards the right path of human development. Inclusive development is far beyond the domain of economics (Sen, 1983). Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) argue that extractive institution is the reason why a nation suffers from poverty. With extractive institutions in place, citizens would lack equal opportunities and political entitlements. And lack of political entitlements makes it harder for people to expand their economic opportunities.

Asian Development Bank (Ali and Son, 2007a, 2007b) conducted studies on the definition of inclusive growth and its measurement. They realized that inequality of opportunities played an important part in income inequality. In 2007, ADB revised its long-term strategic framework and formulated inclusive growth strategy. It is clear that the concept of inclusive development is an enrichment of the concept of inclusive growth.

The term of inclusive development is made up of two parts: "inclusiveness" and "development". According to Sen, development is a process of expanding the real freedom that people enjoys. Inclusive development should be an institutional arrangement that eliminates social exclusion of racial and gender discrimination and ensures equal development entitlement of all for the comprehensive development of human being. Institutions of inclusive development should contain key inclusion that involves human development like economic, social, political, cultural and environmental inclusion.

People‘s understanding of poverty has gone through three stages: income poverty, capability poverty and entitlement poverty. Correspondingly, their understanding of the relations between economic growth and poverty reduction is deepening as well. The pure pursuit of economic growth is gradually replaced by "pro-poor growth" and further evolved to "inclusive growth" and "inclusive development".

Inclusive development is a development pattern where development benefits are tricked down to everyone everywhere. It is about synchronized development of economy, society and humanity. In particular, inclusive development is more about giving equal development opportunities to the poor. Realization of social inclusiveness is both an ultimate goal and a process. Differentiation is a common characteristic in every society. However, it leads to social exclusion of some groups. So to realize inclusiveness, we should eradicate inequality and discrimination through social reforms.

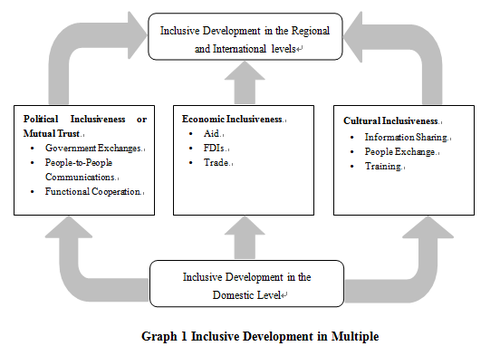

2.2 Inclusive Development from the Perspective of International Relations

Inclusive development often appears as a socio-economic development theory. In nature, it highlights equal benefits of different members in different groups of society. It has more to do with the micro level of individual and society.

Inclusive development can also be interpreted on a macro basis. At the national level, inclusive development can be interpreted as mutual benefit and win-win of countries in the international society. At the regional level, it means harmonious development of various regions and sharing of social development benefits. Nevertheless, widening South-North gap and especially the extreme poverty of some regions in Asia, Africa and Latin America signify that it is impossible for us to realize inclusive development and enjoy the shared fruits of development. In the final analysis, traditional development pattern, to some extent, is exclusive and limited.

Before discussing interactions between China and ASEAN, two things need to be clarified. One is the current situation of social development and poverty in China and ASEAN countries. The other is the historical evolution of China-ASEAN relations.

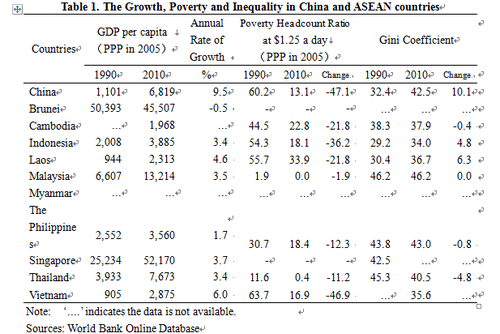

3. Growth, Poverty and Inequality in China and ASEAN Countries

Poverty reduction depends on economic growth and income distribution. Between 1990 and 2010, other than the two developed economies of Brunei and Singapore, 8 ASEAN countries can be divided into three categories based on their economic growth. First, high-growth nations represented by Vietnam with a 6% average annual growth rate; Second, moderate-growth nations with average annual growth rate at 3-5%, including Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia and Thailand, and Laos beats the other three with its 4.6% growth rate; Third, low-growth economies. Philippines, 1.7%. Malaysia, 3.5%. Despite that, per capita GDP of Malaysia hit $13, 214 in 2010, so absolute poverty is eliminated in Malaysia. Different socio-economic development stages of China and ASEAN countries determine their differences in international division of labour. Facilitating trade between China and ASEAN countries can give full play to the comparative advantages of the two sides and allow them to benefit more from growth.

Per capita GDP of China increased rapidly from $1101 in 1990 to $6819 in 2010, an average annual growth of 9.5%, enabling it to join the upper-middle-income countries club and become the second largest economy in the world. Rapid yet inclusive economic growth leads to large-scale reduction of poor populations in China. Poverty incidence ($1.25) rapidly reduced from 60.2% in 1990 to 13.1% in 2010. China‘s current effort of upgrading industrial structure will open the door of opportunity to international redistribution of labour between China and ASEAN and drive economic growth of East Asia.

Between 1990 and 2010, ASEAN countries made tremendous achievements in poverty reduction. In particular, Vietnam and Indonesia stood out with their ratio of poor populations reduced to 46.9% and 36.2% respectively. In 2010, poverty incidence of the two countries decreased to 16.9% and 18.1% respectively. Thailand is about to eradicate ultra-poor populations who live on with less than $1.25 a day.

Nevertheless, challenges remain. In Laos, there are still one thirds of populations living on with less than $1.25 a day, and Cambodia, one fifth. Ratio of poor populations in Philippines and Indonesia is as high as 18%. Therefore, poverty reduction achievements of ASEAN countries are imbalanced, as reflected by the imbalances among and inside nations. For example, poor populations in China mainly concentrate in western region while Indonesian poor mostly live in eastern region.

China‘s income gap is widening with its booming economy. The Gini coefficient rose to 42.5 in 2010 from 32.4 in 1990. Some researchers estimate that China‘s Gini coefficient is now over 50. The widening income gap builds up huge pressure for social stability. Therefore, the Outline for Development-oriented Poverty Reduction for China‘s Rural Areas (2011-2020) identifies bridging development gaps as one of the priorities.

Inequality is not that rampant in ASEAN countries. Three countries that are less equal (Gini coefficient) than others redressed inequality in the past two decades. Although Malaysia is the least equal nation with its Gini coefficient reaching 46.2, its National Development Policy (1990-2000) and National Vision Policy (2000-2010) implemented since 1990 have played an active role in reducing inequality. Substantial inequality in China and Indonesia deserve close attention of other nations when they are devising development strategies.

4. Review and Challenges of China-ASEAN Relations

4.1. The Historical Development of China-ASEAN Relations from the 1990s

In 1991, China and ASEAN established diplomatic relations. The past two decades witnessed rapid development of China-ASEAN relationship. In simple terms, China-ASEAN relationship has mainly gone through the following stages.

A. From the early 1990s until the outbreak of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997-1998

When the Cold War ended in 1990s, the power balance of international system changed dramatically. Especially after the Soviet collapsed, countries started to compete in overall national strength like economic development and scientific advancement in an increasingly multi-polar world, abandoning the traditional pursuit of polarization and military confrontation. Regional organizations flourished as well. In this background, China-ASEAN relationship began to recover and develop.

On the one hand, bilaterally, China established or resumed normal diplomatic relations with all ASEAN countries. In 1990, China established diplomatic relations with Singapore. In 1991, China established diplomatic ties with Brunei. In 1990, China and Indonesia resumed bilateral relation that was suspended for 23 years. In 1991, China normalized bilateral relations with both Laos and Vietnam.

On the other hand, overall China-ASEAN relations developed rapidly in this period. As early as in the mid-1970s, China recognized ASEAN as a regional organization, but it was not until 1991 that China and ASEAN established dialogue relations. In July 1991, Mr. Qian Qichen, then Chinese Foreign Minister, attended ASEAN-China Foreign Ministers‘ Meeting. This was the first time that China talked to ASEAN with the latter being a regional organization. In the following five years, China-ASEAN relations enjoyed fast progress in politics, economy and security. In 1994, China was invited to participate in "ASEAN Regional Forum", thus becoming one of the founders of the forum. Since then, dialogue between the two sides in regional security has begun. Two years later, in July, China became a comprehensive dialogue partner of ASEAN in ASEAN Foreign Ministers‘ Meeting held in Jakarta.

During this period, China also cooperated with Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand in sectors such as poverty reduction, transportation and energy sector.

B. The Turning Point: the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997-1998

The 1997 Asian financial crisis dealt a huge blow to East Asian countries. Southeast Asian countries were once facing grave disasters. Though confronted with huge economic pressure, China did not depreciate its currency or turn its back on the affected ASEAN countries. Its assistance to those countries through international organizations and bilateral channels was deeply appreciated. The financial crisis also ignited the strong desire of countries to promote regional cooperation. In a sense, Asian financial crisis was both a trigger of East Asian regional cooperation and integration and a turning point of China-ASEAN relationship. The financial crisis has three major impacts on East Asian countries as follows.

First, East Asian countries were deeply dissatisfied with the behaviors of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the United States. The Asian Financial Crisis created a kind of ‘resentment’ in East Asia against the IMF as well as the US (Higgott 1998). The inability of the US and other international institutions to help the region, to some extent, made East Asia states frustrated and offered an opportunity for East Asian states to seek an alternative way – a regional solution – to help themselves in the future. After the outbreak of the financial meltdown, in order to stabilize the economy of affected East Asian countries, IMF adopted three policy measures: tightening monetary policy; restructuring the financial system; and opening up economies. It‘s worth noting that those policy measures were exactly the same with those used to solve Latin American financial crisis. But Latin American crisis was mainly due to hefty fiscal deficits. Quite on the contrary, budget of East Asian countries was very low. The crisis was rooted in massive foreign debts of the private sector. It‘s obvious that IMF prescription was not right. Moreover, through IMF, the U.S. asked those countries to make more concessions and forced them to open domestic markets. Many of them were forced to remove restrictions on the proportion of foreign control over domestic financial firms and other industries. But in many affected East Asian countries, those policy measures actually worsened the crisis, making those countries further trapped in the financial crisis. Hence, they were awakened to see that those policy measures were actually reforms under the "Washington Consensus" system and represented interest of the U.S. and US-led IMF rather than that of affected East Asian countries.

Second, the financial crisis made East Asian countries realize their close connections with one another. Economically, East Asian countries formed close trade and investment network and relied on one another in terms of economic development. But the reliance was bottom-up, and was mainly the result of spontaneity of the market mechanism. And it lacked institutional support and guarantee at the regional level, so was vulnerable and instable. Once crisis occurred, what happened in one country would soon be happening in other countries. Their united fates would lead to wider economic crisis. Therefore, East Asian countries hoped to put in place their own regional cooperation mechanism to recover economy and establish regional institutional support for the prevention of similar crisis in the future.

Third, and most importantly, East Asian countries were brought home to regional awareness, or in other words, collective identity. Historically, the region of “East Asia” and which countries constitute East Asia were ambiguous. The Asian financial crisis provided East Asian countries including China and ASEAN countries with an opportunity to rethink their own identity. There was a sense rising from states in both Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia that they were in the same region and that was East Asia. Through the crisis, the East Asian states learnt to use a regional approach so that they would deal better with similar problems in the future. One lesson learnt from the bitter experience of the Asian Financial Crisis was that it was necessary for the East Asian states to create a regional institution that was not dependent on the US.

C. Regional Cooperation and China-ASEAN Relations after the Asian Financial Crisis (1997-2005)

The ASEAN+3 Cooperation Mechanism emerged against this backdrop. At the 4th ASEAN+3 Summit in November 2000, Zhu Rongji, then Chinese premier, put forward the suggestion of establishing a free trade area (FTA). In March, 2001, China-ASEAN Panel was set up to conduct feasibility analysis of such a suggestion. In November, 2001, at the 5th ASEAN+3 Summit, China and ASEAN announced the plan of building China-ASEAN Free Trade Area within a decade.

With the establishment of China-ASEAN Free Trade Area, relations between the two sides were deepened. At the end of 1997, China and ASEAN established partnership of good neighborliness and mutual trust oriented towards the 21st century. Right after the announcement of FTA plan, in October, 2003, at the 7th ASEAN-China Summit, China became the first non-ASEAN country to sign ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation. Then, China and ASEAN signed Joint Declaration on ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity. The Declaration served as an important strategic guidance for stable and profound development of China-ASEAN relationship in the future. And this was the time when China-ASEAN relationship transformed from partnership of good neighborliness and mutual trust to strategic partnership. China is the first strategic partner of ASEAN, and ASEAN is the first regional organization that China enters into strategic partnership with.

In terms of aid, China canceled debts of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam in 2002. China provided RMB190 million interest-free loans and RMB50 million grants to Laos for construction of the section of Kunming-Bangkok expressway in Laos. China also initiated Chinese-funded projects in ASEAN countries such as Thailand, Cambodia and Laos. In 2004 when tsunami hit Southeastern Asia, China provided disaster areas with funds worth of RMB520 million and $20 million. At the end of 2005, China announced that in the following 3 years it would provide 1/3 of its concessional loans for developing countries to ASEAN countries.

D. Trade and Poverty Reduction have become the Key Focuses of China-ASEAN Cooperation (2006-2012).

In January 2010, the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area (CAFTA) was finally established. It enables trade between China and ASEAN counties to occupy 13% of the world‘s total, making itself a huge economy that contains 11 countries in the region with a combined population of 1.9 billion and an aggregate GDP of up to $6 trillion. At present, the CAFTA is not only the world‘s most populous free trade area, but also the largest one among developing countries. China is now the largest trading partner of ASEAN, and ASEAN the third largest trading partner of China. The total trade between China and ASEAN grows rapidly. Trade facilitation has undoubtedly contributed to economic growth and poverty reduction in China and ASEAN members.

Eliminating poverty to promote sharing of social development fruits is the common ideal of humanity and common task of China and ASEAN nations. In 2007, the First China-ASEAN Social Development and Poverty Reduction Forum" was held in Nanning. China and ASEAN nations jointly released Nanning Initiative, calling for concerted efforts to facilitate social development and poverty reduction in China and ASEAN nations with a view to realizing balanced development within nations and in the region. The launch of such a forum provides policy-makers, theory researchers and development practitioners in China and ASEAN countries with a platform for the sharing of social development and poverty reduction policies and experience.

Cooperation on poverty reduction is incorporated into Plan of Action to Implement the Joint Declaration on ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity (2011-2015). In the five year plan, cooperation on poverty reduction mainly includes: 1. Enhance cooperation on poverty reduction, establish regular contact and policy consultation mechanism for competent authorities, continue to hold China-ASEAN Social Development and Poverty Reduction Forum; 2. Continue to hold a range of anti-poverty policy and practice symposiums for ASEAN nations, provide ASEAN members with academic degrees of poverty reduction and development and strengthening cooperation on human resource development; 3. Foster partnership through visits, knowledge sharing, information exchange and joint research; 4. Offer policy advices and technical support on request and participate in project designing and anti-poverty strategy-making.

4.2 Constraints and Challenges in China-ASEAN Relations

China and ASEAN have opened new chapters of cooperation on economy, politics and security aspects. However it does not necessarily mean that there is no problems in their relations. Currently there are still many constraints which could hamper the development of China-ASEAN relations.

A. The Competition between Different Aid Models in International Development

After the Second World War, the structure of the international system shifted dramatically. Some developed countries disseminated universal values of the West through "development aid" and "Washington Consensus". However, over the past three decades, developing countries have been increasingly concerned with growth and poverty reduction. The waning "Washington Consensus" and increasingly powerful influence of the "China Model" get on the nerves of Western countries. Therefore, they whipped up "China Threat" to compete for a stronger voice. "China Treat" has been sprawling in Southeastern Asia. The Chinese government responds by adopting the Peaceful Development Strategy. In Southeast Asia, China‘s Peaceful Development Strategy is embodied by policies of good neighborliness and friendship. But still, many ASEAN countries tend to doubt China‘s regional strategic intent and fear China‘s economic revitalization. In recent years, the exact wording of "China threat" is not frequently found as before in official documents or government reports of neighboring countries. However, some ASEAN countries started to use words like "worry" and "concern" to express their anxiety.

B. Similarities and Competitiveness of Economic Structure between China and ASEAN Countries

China has similar economic development level and industrial structure with many ASEAN developing countries. Our economy is all dominated by agriculture and labor-intensive industries. At the same time, we all depend on the same third markets such as US, Japan and EU. China has grown into "the workshop of the world", whereas ASEAN countries have been losing many market shares in Japan and US since mid-1990s and especially since the beginning of this century. This is largely due to the overlap of the export structure between China and ASEAN export structure. Furthermore, foreign direct investment (FDI) is also an area of fierce competition. As early as in the early 1990s, ASEAN countries attracted over 60% of global FDI in Asian developing countries, while in the same period, China only received 20% of FDI. However, things have changed since the beginning of this century. China now has over 60% of FDI, whereas ASEAN countries only have less than 20% (Glossman and Brailey 2002).

C. The Dispute of South China Sea

The dispute of South China Sea is very thorny in China-ASEAN relationship. It cannot be solved overnight. Therefore, how to properly handle the issue without handicapping China-ASEAN economic cooperation and sound development is a common task of both sides.

D. The Impact of US’ strategy of ‘Return to Asia-Pacific’

Since 2009, the US has made a number of high-profile moves to return to Asia-Pacific region. For example, it entered into Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia in 2009 and participated in East Asia Summit. Given the current situation, China and many ASEAN countries are not deliberately against American presence in this region. To some extent, US can act as a stabilizer and contribute to regional security. But it also brings with it more uncertainties to the sophisticated relationship in East Asia. Therefore, how to make full use of its presence in Asia and avoid its excessive intervention and manipulation in China-ASEAN relationship and regional affairs, and serve the interest of China and ASEAN countries are questions to be answered by China and ASEAN countries.

E. The Interactions of Great Powers in East Asia

East Asia (including Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia) is a region that includes different interests of many powers in the world. This region has two regional great powers, namely China and Japan, and many nations outside the region like the US. From 2005 when the East Asian Summit was established, India, Australia and New Zealand were included in the framework of regional cooperation in East Asia. The interaction between the different states inside and outside the region raises the uncertainty for regional cooperation and China-ASEAN relations.

5. Policy Suggestions

First of all, China and ASEAN countries should improve their political mutual trust and to promote inclusive development and poverty reduction. How to improve political mutual trust? The answer is through enhancing interaction, especially cultivating China-ASEAN common awareness. China needs to allow ASEAN to benefit from China‘s economic rise, which conforms to the connotation of inclusive development at state-to-state level and can contribute to mutual benefit and win-win. In a sense, China-ASEAN FTA and especially the "Early Harvest" program are excellent footnotes to such an outcome. The Chinese government hopes that through close economic cooperation China-ASEAN political relations could be enhanced. Meanwhile, and g South China Sea issue could be solved in a more harmonious and peaceful way. If the economic gap between China and ASEAN countries widen, South China Sea issue would make small countries in Southeast Asia more concerned with China‘s rise. If Southeast Asian countries can ride on China‘s economic boom and benefit from it, their worries about China would be eased.

Those are far from enough. It is true that the establishment of the China-ASEAN FTA has provided many ASEAN countries with more opportunities to enter into China‘s market, promoted development of trade and investment, and bridged state-to-state wealth gaps of ASEAN countries and reduced proportion of populations in poverty. However, it does not necessarily mean that local people in ASEAN countries benefit from the arrangement. For example: ASEAN countries accuse China of investing in Southeast Asia in an environmentally-unfriendly way just for local resources. In addition, more and more Chinese domestic companies go abroad. Some of them did not have the awareness of corporate social responsibility. They cannot increase job opportunities and bring benefits to the locals. To some extent, it led to the dissatisfaction with Chinese companies and people and thus influenced China-ASEAN relations negatively.

Therefore, besides economic cooperation, cooperation in social development and poverty reduction could be a new way to promote China-ASEAN relations. It is also a practice of inclusive development on the regional level.

Facilitating anti-poverty cooperation between China and ASEAN countries offers a new breakthrough to deepen China-ASEAN relations. Poverty alleviation and development are mutual goals of both China and ASEAN. China is the largest developing country, which has achieved great progress in poverty reduction. It can offer many experiences for developing countries in ASEAN. Therefore, through exchanges, dialogues and cooperation on poverty reduction and fostering awareness of common interest and strategy help eliminate misunderstandings and concerns of Southeast Asian countries towards China. Meanwhile, it helps build mutual trust and thereby develop a more sustainable and stable China-ASEAN relations.

Second, China and ASEAN countries should promote aid, trade and FDIs in order to achieve economic inclusiveness. In terms of trade, both sides should enhance coordination between China and ASEAN in trade facilitation. To the end, three aspects should be emphasized. One is to promote a unified regional standard for China-ASEAN Free Trade Area. The second is to increase the transparency of trade policies. The third is to expand the investment in infrastructure. In terms of FDIs, China and ASEAN should promote cooperation related to livelihoods and poverty reduction, such as agriculture and fisheries. In terms of aid, besides the traditional aspects of aid, such as infrastructure, China and ASEAN should emphasize developing the capacity of the poor. To the end, some of China’s experience in some African countries could be a good example. For instance, the International Poverty Reduction Center in China (IPRCC) aided the Peiyapeiya Community Service Center in Tanzania. It implemented a Community Development Demonstration Learning Project to enhance the capacity of the locals. Based on their own conditions and demands, China and ASEAN countries could design their own cooperative projects to build the capacity of the poor in both countries.

Third, the mechanism of China-ASEAN Forum on social development and poverty reduction should be institutionalized. So far, the Forum has been held annually. However, the Forum should not merely be taken as a platform of idea exchanging. How to use the mechanism to promote the practices of China-ASEAN cooperation on poverty reduction will be of great significance.

Finally, to achieve cultural inclusiveness, China and ASEAN countries should reinforce people-to-people communications and knowledge sharing in the field of poverty reduction. China and ASEAN countries should promote cooperation through various cooperation mechanisms such as ASEAN+3 and ASEAN+1 (China) and also the International Poverty Reduction Center in China (IPRCC). Both sides should hold international workshops, forums and seminars on development and poverty reduction so as to provide ASEAN developing countries with comprehensive technical support. In addition, efforts should be made to improve depth and capacity of research on anti-poverty cooperation, and to reinforce trainings and to promote academic exchanges. In doing so, China and ASEAN countries could deepen mutual understanding between each other.

References

Acemoglu D. and J.A.Robinson (2012), Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, Crown Publishers

Ali,I.and H.H.Son. (2007a), “Defining and Measuring Inclusive Growth: Application to the Philippines ”.ERD Working Paper No.98. http://www.adb.org/economics.

Ali, I. and H. H. Son. (2007b),“Measuring Inclusive Growth. Asian Development Review.”Asian Development Review ,10(24):11-31.

Ali,I. and J.Zhuang.(2007),“Inclusive Growth toward a Prosperous Asia:Policy Implications.” ERD Working Paper No.97, Manila: Economic and Research Department, Asian Development Bank.

Bourguignon, F. (2003), “The Growth Elasticity of Poverty Reduction: Explaining Heterogeneity across Countries and Time Periods.” Inequality and Growth: Theory and Policy Implications, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ceverino,R.C.(2008),ASEAN-China Relations: Past, Present and Future, ASEAN Studies Centre, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, at the Third China-Singapore Forum Singapore, 17 April 2008

Deininger,K., and L. Squire(1996),“A New Data Set Measuring Income Inequality.” World Bank Economic Review 10(3): 565–591.

Dollar, D., and A. Kraay (2002),“Growth Is Good for the Poor.” Journal of Economic Growth,7(3):195–225.

Higgott, R. (1998),The Asian Economic Crisis: a Study in the Politics of Resentment. New Political Economy, 3 (3), pp.333-356.

Ganesh, R., and R. Kanbur(2010),“Inclusive Development: Two Papers on Conceptualization, Application, and the ADB Perspective”. Working Paper, Independent Evaluation Department, ADB.

Glosserman, B. and Brailey, V.(2002), ASEAN Needs to Unite, or Fade in China’s Shadow. South China Morning Post, 11 November.

Grosse, M.,K. Harttgen, and S. Klasen (2008),“Measuring Pro-Poor Growth in Non-Income Dimensions.” World Development Report. 36(6):1021–1047.

Kakwani, N., and H. Hyun. (2004)“Pro-poor Growth: Concepts and Measurement with Country Case Studies.” The Pakistan Development Review, 42(4):417-444.

Klasen, S. (2008),“Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction: Measurement Issues in Income and Non-Income Dimensions.” World Development, 36(3):420–445.

Klasen, S.(2010),“Measuring and Monitoring Inclusive Growth: Multiple Definitions, Open Questions, and Some Constructive Proposals.” Working paper. Asian Development Bank.

McKinley, T. (2010),“Inclusive Growth Criteria and Indicators: An Inclusive Growth Index for Diagnosis of Country Progress.” working paper, Asian Development Bank.

Ravallion M. and S. Chen(2003), “Measuring Pro-Poor Growth”, Economics Letters, 78(1):93-99.

Ravallion, M.(2004),“Pro-poor Growth: A Primer, Policy Research.” Working Paper World Bank.

Roemer, J. 1998. Equality of Opportunity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sen A.(1983).“Development: Which Way Now?”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 372(93):745-762.

Stiglitz, J. (2004), The Roaring Nineties: a New History of the World’s most Prosperous Decade. New York: W.W.Norton.

White, H., and E. Anderson.(2001),“Growth vs. Redistribution: Does the Pattern of Growth Matter?” Development Policy Review, 19(3):167-289.

Zhuang, J. (2010), Poverty, Inequality, and Inclusive Growth in Asia: Measurement, Policy Issues, and County Studies, ADB.

Public Policies for Inclusive Development and Poverty Reduction--China‘s Experience

TANG Min

Counselors of the State Council

Experts Committee of the Leading Group of Poverty Alleviation and Development of the State Council

I. Foreword

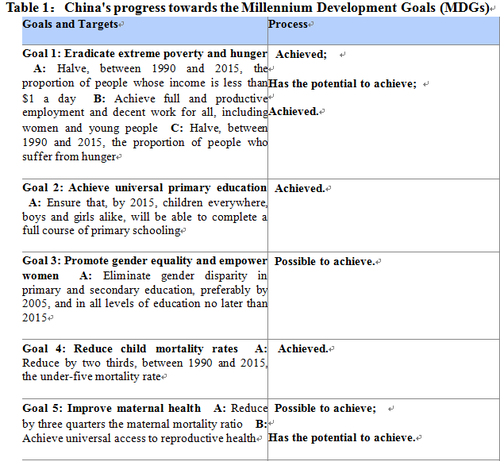

China‘s development-oriented poverty reduction program constitutes an important component of global inclusive development. China is a developing country with the largest population in the world, featuring a poor economic foundation and noticeable unbalanced development between urban and rural areas, and among different regions and groups, which renders the mission to reduce poverty particularly difficult. Thanks to efforts made over the past 30 years, the problems of subsistence, food and clothing for China‘s rural residents have been basically solved, the production and living conditions of the poor have been markedly improved, and the level of social development has been enhanced. At present, China has realized, ahead of schedule, the goal of cutting the poverty-stricken population by half, and other goals listed in the United Nations Millennium Development Goals, thus making great contributions to the world‘s poverty reduction efforts.

This paper, on the basis of China’s experience of inclusive development, focuses on government’s policies in rural poverty reduction program and its results. The first section discusses the concept of inclusive development. The second section reviews China’s poverty reduction process and achievements in the past 30 years. The third section elaborates on the policies and achievements of the development-oriented poverty reduction program. The fourth section describes the outlook of public policy for inclusive development and poverty reduction.

II. The Concept and Development of Inclusive Development

2.1 Concept of inclusive development

Inclusive development, according to definitions made by international organizations, such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, means to “spread the benefits of economic globalization and economic development among all economies, regions and people and to realize balanced economic and social progress through sustainable development.” The international community, in general, has taken "inclusiveness" as focusing on people’s equal development, avoiding "social exclusion", and reducing poverty and unemployment. While stressing economic development, inclusive development also pays much attention to the pattern of economic growth, the process which all members contribute to growth, the disadvantaged group, and the equality in allocation and call for the growth that can bring jobs.

2.2 Inclusive Development and Equal Opportunity

It is worth noting that the equality advocated in inclusive development refers to equality of opportunities, not in income. The World Development Report 2006 points out that equity means, at first, equality of opportunity, which should be an indispensible part of all developing countries’ successful poverty reduction strategy. Mr. Bourguignon, former World Bank chief economist, puts forward that, “Equity and prosperity are complementary. Greater equity is thus doubly good for poverty reduction: through potential beneficial effects on aggregate long-run development and through greater opportunities for poorer groups within any society.” Mr. Paul Wolfowitz, former President of the World Bank, said, “Public action should seek to expand the opportunity sets of those who, in the absence of policy interventions, have the least resources, voice and capabilities. It should do so in a manner that respects and enhances individual freedoms, as well as the role of markets in allocating resources.”(World Bank, 2006)

Therefore, in order to make the social and economic development more inclusive, we should make policies to address the longstanding problem of the inequality of opportunities. These policies include: (1) investing in human capital, expanding health and education services, and providing a safety net for vulnerable groups; (2) expanding the poor’s opportunities to get access to economic infrastructure like land, road, water, electricity, sanitation, and communications; (3) promoting the benefits of the judicial system, finance, labor and product markets. In these ways, the poor will be easier to get employment and development opportunities.

International markets should also maintain equity, especially in the aspects of labor, materials, creativity, and capital market. Rich countries should increase the flow of labor from developing countries, promote the process of trade liberalization in the WTO Doha Round, provide more trade and investment opportunities for poor countries, and make appropriate international trade and financial rules for developing countries. Meanwhile, they should increase development assistance and improve its efficiency.

2.3 Inclusive Development and Government

The government shoulders major responsibility to realize inclusive development. World Bank pointed out in The World Development Report 2008 that “successful cases share a further characteristic: an increasingly capable, credible, and committed government. Growth at such a quick pace, over such a long period, requires strong political leadership. Policy makers have to choose a growth strategy, communicate their goals to the public, and convince people that the future rewards are worth the effort, thrift, and economic upheaval. They will succeed only if their promises are credible and inclusive, reassuring people that they or their children will enjoy their full share of the fruits of growth. Such leadership requires patience, a long planning horizon, and an unwavering focus on the goal of inclusive growth.” (World Bank, 2008)

Lin Yifu, former World Bank chief economist, also repeatedly reminds us the deficiencies of the “Washington Consensus” and the significance of reevaluating the important role of government in economic development. He indicates that many economic theories proposed in the past are just a summary of the experience in developed countries in later stage, and the role of government is not so prominent, therefore, economic theory generally stresses market and ignores the role of government. For those developing countries in the early and mid- stage of development, we should not only recognize the limitations and the problems of the “Washington consensus”, but also surpass the traditional Keynesian fiscal stimulus policies and target investment in the real economy, which can improve productivity and eliminate growth bottlenecks, as the main object of the public fiscal stimulus.

As for the government’s inclusive development policies, the World Development Report 2008 of the World Bank focuses on four important aspects. (1) Encouraging competition, achieving equality of opportunity, protecting individuals, and realizing the equity in outcome. (2) Promoting industrial upgrading and transformation through policy-orientation. (3) Safeguarding the rights and interests of workers. (4) Ensuring the survival of the disadvantaged groups by profit-sharing system and redistribution policy.

2.4 Inclusive Development in China

In fact, the people-oriented scientific concept of development put forward by the Chinese government coincides with the concept of inclusive development. The transformation of economic development modal is an important manifestation of inclusive development in China. In April 2011, at the opening ceremony of the Boao Forum for Asia, Chinese President Hu Jintao made a speech under the theme of “Inclusive Development: Common Agenda and New Challenges”, expounding China‘s views on the concept as well as China’s practice of "inclusive development." Prior to this, Hu Jintao made two speeches on “inclusiveness”. One was his speech “Deepen Exchanges and Cooperation for Inclusive Growth” at the Fifth APEC Human Resources Development Ministerial Meeting in September, 2010. Two months later (October 2010), he stressed again “to advocate inclusive growth and increase the endogenous dynamic of economic development” at APEC Leaders‘ 18th Informal Meeting. (Hu Jintao, 2010, 2011)

The Chinese government has, on several occasions, made it clear that China is willing to actively promote the world’s inclusive development, expand exchanges and cooperation with other countries, and address common challenges, which includes the following four aspects.

First, we should be inclusive to the path of development of other countries, respect the diversity of different civilizations in the world, respect the right of each country to pursue the development path of its choice and explorations in economic and social development, and promote international cooperation on this basis.

Second, we should achieve upgrading of the economy by scientific and technological progress and developing green economy. Efforts should be made to obtain balance and interaction of all aspects of economic and social development, the parallel development of the real economy and the virtual economy, the balanced development of the domestic market and the international market, as well as coordinated development of economic and social development.

Third, all countries should not only abandon “beggar thy neighbor” policy, but also help each other, with the big helping the small, the rich helping the poor, so that all members can share the benefits of globalization and integration and peoples‘ lives can be improved.

Fourth, countries should seek common ground while reserving differences to achieve common security, mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality and cooperation. Disputes between countries should be settled by dialogue and consultation rather than confrontation.

III. Inclusive Development and Achievements of Poverty Reduction in China

Over the past 30 years, China has made historic progress in poverty reduction, which has become an important part of China’s inclusive development. Estimated by China’s official poverty line, China’s rural poverty-stricken population has reduced from 250 million in 1978 to 26.88 million in 2010. If estimated according to the World Bank’s poverty standard of $ 1.25 per person per day, the global poverty-stricken population, including China, has decreased from 1.94 billion in 1981 to 1.29 billion in 2008. During the same period, the number of the Chinese poverty-stricken population has fell from 850 million to 170 million, a decrease of 660 million, which is slightly more than the number of global poverty reduction. Evidently, the world‘s poverty-stricken population will not reduce but increase. The position and role of China’s development-oriented poverty reduction program in international poverty reduction has attracted worldwide attention and is widely recognized. (China Development Research Foundation, 2007)

Since its launch in the early 1980s and followed by nearly 30 years of adjustment and changes, the history of China’s development-oriented poverty reduction can be divided into four stages as follows.

The first stage was regional poverty reduction period (1978-1985). At the beginning of reform and opening up, the system of contracted responsibilities on the household basis with remuneration linked to output was implemented. The price of agricultural products was raised by a big margin in the reform of the rural economic system. Farmers‘ enthusiasm in production was aroused. The output of agricultural products increased remarkably, and the income of the farmers rapidly increased. Therefore, the problem of impoverishment in the rural areas eased up. Since 1982, the Central Government has launched poverty reduction program for ‘‘three Xis‘‘ (Dingxi and Hexi prefectures in Gansu Province, and Xihaigu Prefecture in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region). In these areas, ethnic minority people live in concentrated communities. The Chinese government helped these poor areas protect ecology and develop agricultural production. This stage witnessed a decrease of the national rural poverty population from 250 million to 125 million, with an average annual reduction of 18 million, and the incidence of poverty declined from 33.1% to 14.8%. (World Bank, 1994)

The second stage observed a large scale the program of helping the needy people lasted from 1986 to 1993. The Chinese government decided to carry out a large scale program in order to help people through development in a planned and organized manner. The State Council set up a special working group and earmarked special funds. By the end of 1993, the number of poor people in rural China had dropped from 125 million to 80 million, and the rate of poverty occurrence fell from 14.8% to 8.7%. (Leading Group on Poverty, 2000)

The promulgation and implementation of the Seven-year Priority Poverty Reduction Program in March 1994 marked the third stage. The plan called in explicit terms for amassing the financial resources to solve the problem. The help-the-poor discount-interest loan provided employment as a form of relief and financial support for development. The funds for three poverty reduction projects increased 1.63 times from 1995 to 1999. China’s poor population reduced to 34 million, and the rate of poverty occurrence dropped from 8.7 % to about 3%. (Rural Investigation Team, 2000)

The implementation of the Outline for Poverty Reduction and Development of China‘s Rural Areas (2001-2010) marked the fourth stage. After the completion of Seven-year Priority Poverty Reduction Program, rural poor population is mostly located in degrade hilly lands where the living environment is very harsh, high mountains regions, arid areas with water shortage, and frontier minority concentrated areas. It is rather difficult get these poverty groups out of poverty only by development-oriented poverty reduction program. In June 2001, the State Council formulated the Outline for Poverty Reduction and Development of China‘s Rural Areas (2001-2010), which changed previous poverty reduction modal of helping impoverished counties. The State Council decided to target at impoverished villages as their program. (State Council, 2001) The key was to make village as a unit for the comprehensive development if we want to develop science and technology, education, medical and health undertakings in poverty-stricken areas and lay emphasis on participation in poverty reduction program. During this period, the government repeatedly increased poverty threshold, but the poverty population was on the rise all the time. By the end of 2010, the rural poor population reduced to 26.88 million (Bureau of Statistics, 2012).

After four stages in nearly three decades of help-the-poor campaign, development-oriented poverty reduction program in China has made great achievements. The achievements include the following aspects. (1) Rural poor population dropped significantly. (2) The infrastructure has been greatly improved, standards of social undertakings has been risen. (3) The trend of ecological deterioration has been slowed down. (4) County economy developed rapidly. China has accomplished the Millennium Development Goals of the United Nations to a considerable extent ahead of schedule (see Table 1).

Since 2005, the rate of poverty reduction in China has accelerated dramatically, particularly in the following aspects. First, the rural poor population is significantly reduced. In terms of the then newly adjusted official poverty line, the incidence of poverty in rural areas decreased from 6.8% to 3%.

Second, the living condition of the poor areas has been improved. The average annual growth of per capita consumption expenditure in the key counties reached 11.5% in real terms, and their per-capita housing space increased 2.4 square meters. The proportion of owning the refrigerator, TV, fixed telephone per 100 households has increased significantly.

Third, we have significantly improved the condition of the infrastructure in poor areas. The rural households’ accessibility to safe drinking water increased from 55% to 61%, to roads in villages increased from 79% to 87%, to electricity jumped from 96% to 98 %, and to radio and television increased from 88% to 95%.

Fourth, the social undertakings in poor areas have been remarkably improved. The rate of having a clinic in administrative villages of national Key County increased from 74% to 80%. The ratio of having qualified doctors and hygienists in rural areas has increased from 75% to 79%.

Fifth, the trend of deterioration of the environment in poor areas has been further curbed. From 2005 to 2009, the national key county has returned 3700.3 million mu of farmland to forest and grassland, and we have relocated 2.245 million impoverished populations from environmentally unfriendly.

Sixth, we have witnessed a faster development of county economy in poor areas. The average annual growth rate of per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in national Key County reached 18.81%. The average annual per-capita local budgetary revenue grew at 24.5%.

IV. Policies and Its Implementations of Development-Oriented Poverty Reduction

4.1. The evolution of poverty reduction policies

In addition to a series of poverty alleviation and opening-up policies released in the early stage, over the past decade, development-oriented poverty reduction program is included in the overall plan for national economic and social development, and a series of new policies and measures conducive to the development of poor rural areas have been implemented. (Zhang Lei, 2007) These policies mainly include:

First, the government should accelerate the implementation of rural development policy. The government made rural people in China bid final farewell to the payment of agriculture tax that had existed in China for over 2,600 years and issued subsidies directly to grain growers, subsidies for purchasing fine seeds and agricultural machinery and tools and general subsidies for purchasing agricultural supplies; pushed forward the construction of infrastructure related to drinking water, electricity, road and methane, along with the renovation of dilapidated rural housing. Meanwhile, the government kept increasing investment into measures that strengthen agriculture and measures that bring benefits to the farmers and increase their incomes, as well as the development-oriented poverty reduction program. The outlays of the central finance on agriculture, the countryside and farmers increased at an annual rate of 21.9 percent on average. We carried out the policy to exempt rural students in compulsory education from poor families from paying tuition and miscellaneous fees, and to provide living subsides for boarders. The state has been vigorously developing vocational education. From 2001 to 2010, some 42.89 million students graduated from secondary vocational schools, and most of them were from rural families or impoverished urban families. The central government gave considerable financial support to central and western regions in terms of subsistence allowances for rural residents, new cooperative medical care and new social endowment insurance for rural residents.

Second, the government should accelerate the implementation of regional development policies for western regions. Compared to other regions of China, Western China has rather adverse natural conditions, underdeveloped infrastructure and a larger population of the poor. At the end of the 20th century, the Chinese government started to carry out the strategy of large-scale development of the western region. In the last decade, water conservancy projects, projects of returning cultivated land to forests and projects of resource exploitation, as planned in the strategy of developing the western region, were launched; the labor force of poor areas was given preference in infrastructure construction projects to increase the cash income of the poor. The government worked out and implemented a series of policies for regional development to promote economic and social development in poverty-stricken areas and areas inhabited by smaller minority groups.

Third, the government should establish the rural social security system. To provide basic social security for the poverty-stricken population is the most fundamental way to steadily solve the problem of adequate food and clothing for those people. In 2007, the state decided to establish a rural subsistence allowance system throughout the rural areas. By the end of 2010, the system covered 25.287 million rural households, totaling 52.14 million people; the average standard for rural subsistence allowance is 117 yuan per person per month, and the average subsidy is 74 yuan per person per month. In 2009, the state launched a pilot scheme of a new type of social endowment insurance for rural residents in some places. By 2011, the scheme had extended to 60 percent of rural China, covering 493 key counties in the national development-oriented poverty reduction programs, accounting for 83 percent of such counties. The central finance subsidizes central and western China all the basic funds for old-age pensions in line with the standards decided by the central government, and subsidizes 50 percent of such funds for eastern China.

Fourth, the government should promote overall economic and social development in poverty-stricken areas. The state designated 148,000 impoverished villages nationwide in 2001. It also formulated poverty reduction programs for each and every village covering basic farmland, drinking water for people and livestock, roads, income of poor villagers, social undertakings and other areas. The government pooled and allocated funds for the implementation of the programs on a yearly basis. By the end of 2010, some 130,000 villages had implemented the programs.

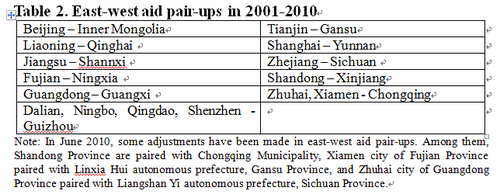

Fifth, the government should combine special poverty reduction actions with industrial and social efforts. The state works out special programs for development-oriented poverty reduction and carries them out on a yearly basis. The state gives full play to the functions and responsibilities of the various industrial departments, and makes poor areas the top priority for each industry‘s and department‘s development. The state mobilizes and organizes all sectors of society to give various forms of support to poor areas in their development. (Lin Yifu, 2008) Party and government departments, enterprises and public institutions give special support to designated poor areas, eastern and western China cooperate to reduce poverty, and all sectors of society participate in this program -- a poverty reduction model with Chinese characteristics, which helps poor areas to develop and poor farmers to increase their incomes. (See Table 2)

Note: In June 2010, some adjustments have been made in east-west aid pair-ups. Among them, Shandong Province are paired with Chongqing Municipality, Xiamen city of Fujian Province paired with Linxia Hui autonomous prefecture, Gansu Province, and Zhuhai city of Guangdong Province paired with Liangshan Yi autonomous prefecture, Sichuan Province.

Sixth, the government should combine outside support with self-reliance. China has made full use of foreign investment to accelerate its poverty reduction pace. By 2010 a total of 1.4 billion U.S. dollars in foreign funds had been poured into poverty reduction in China. About 110 foreign-funded poverty reduction projects had been implemented, covering 20 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the central government) and more than 300 counties in central and western China, and benefiting nearly 20 million impoverished people. China has brought in from abroad some advanced concepts and successful approaches in its efforts to reduce poverty, such as participatory poverty reduction, small-sum loans, project appraisal and management, and poverty monitoring and evaluation. (Wang Chaoming, 2012)

Seventh, the government should conduct financial poverty reduction. Since 2006, the state has tried out an experimental mutual funding program in 14,000 impoverished villages, allocating 150,000 yuan to each of the villages to support local production in line with the principles of “owned by the people, used by the people, managed by the people, enjoyed by the people, cyclical usage and spiral development.” From 2001 to 2010, the central government granted nearly 200 billion yuan of poverty reduction loans. The comprehensive reform of the state administrative system of poverty reduction loans in 2008, in particular, further motivated local governments and financial institutions to engage in development-oriented poverty reduction, and effectively helped needy people to get such loans by introducing the market competition mechanism, expanding the operational authority of the loan-issuing bodies, and delegating greater power to lower levels in the management of interest-discounted funds, among other measures.

4.2. Existing problems

The current poverty reduction program needs improvement. First, the poverty standard is not compatible with the development of social and economic development. In the mid-1980s, the government developed a rural poverty line suitable to the level of development (i.e., subsistence line), and has been in use for quite a long time. After two decades had past, China‘s per capita GDP has doubled several times, and the poverty line to rural per capita net income ratio fell from 52% in 1985 to 21 % in 2005. Compared with other countries, this proportion is almost the lowest. (Han Jialing, 2009)

Another problem of eradicating poverty is the widening development gap. In 2009, the ratio of China‘s urban income to rural residents’ income expanded from 3.1:1 in 2002 to 3.3:1. At the same time, the income gap between different rural residents is also expanding. In 2002, the per capita net income gap between high and low income groups was 6.8:1; however, it jumped to 8:1 in 2009. Severe imbalanced development has become more prominent in underdeveloped regions with special difficulties that lie in vast and contiguous stretches.

Moreover, our poverty reduction achievement is unstable. Although China has made great progress in poverty reduction, poverty reduction achievements still need to be consolidated. According to the data from National Bureau of Statistic, in 2009, 62.3% of the 35.97 million poor people are those who sink back into poverty.

All those problems coupled with China’s vast territory have made various reasons for poverty problem in China. The severe natural disasters, fluctuations in the agricultural products markets, the complexity of the external environment and other factors have further increased the difficulty to eradicate poverty. According to statistics, the chance of occurring severe natural disasters in poor areas is five times higher than that of other regions. (Sun Fachen, 2012)

Finally, special groups require more specific policies. National minorities, women, children, the elderly, the disabled, and those suffering from endemic diseases, due to their special social attribute, have become the disadvantaged groups in the process of social development because over the time, the poverty reduction policy is difficult to meet the development needs of these different groups. One of the challenges in the new stage of poverty reduction is to develop differentiated supportive policy for these special groups.

V. Inclusive Development and Public Policy Outlook for Poverty reduction

Eradicating poverty, improving people‘s livelihood, and achieving common prosperity are the core of the inclusive development and also the essential requirements of the socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics. To this end, the Chinese government has made the “Outline for Development-oriented Poverty Reduction for China‘s Rural Areas (2011-2020)” (herein after referred to as Outline) to deploy the new round of poverty reduction work. (State Council, 2012)

5.1. Overall Objective

The overall objective in the Outline is that, by 2020, adequate food and closing, compulsory education, basic medical care and housing will be available to poor population. Moreover, per capita net income growth rate of poor peasants will be higher than national average, leading indicators of basic public services will be close to the national average, and the widening development gap will be bridged overtime.

One of the most important features of the new Outline is the drastic increase of the poverty line. After years of effort, by the end of 2010, China’s poor population has decreased to 26.88 million if calculated according to the original poverty line of have an annual income lowering than 1,274 yuan. In the new Outline, the central government has decided to raise the poverty line to 2,300 yuan in terms of the per capita net income of peasants. The new poverty line will have made 128 million people eligible for government anti-poverty subsidies, which accounts for 13.4% of the rural population. The drastic increase can get more people covered by the policy, which not only tallies with the reality of China’s economic and social development, but also shows the strong determination of the central government to solve the livelihood problems for rural population and to strive to narrow the development gap between urban and rural areas. According to the Director of the Leading Group Office on Poverty Alleviation and Development (LGOP) Fan Xiaojian, “The improvement of this standard means that our poverty reduction has entered into a new stage, which is a sign of the great achievements we’ve made in the first period of poverty reduction.” (Fan Xiaojian a,2012) If we calculate it in accordance with the international purchasing power, the new poverty line is equivalent to $1.8 per day per person, which is higher than the $1.25 per day per person international poverty standard designed by the World Bank in 2008.

According to the Outline, in the next decade, China will make the contiguous poor areas with special difficulties the key target areas, and make quicker access to food and clothing and helping people shake off poverty faster the top priority. Currently, all departments are making plans for contiguous poor areas with difficulties to increase investment in contiguous destitute areas and address, one by one, prominent problems in infrastructure, industrial development, production and living conditions, human resource development, investment in people’s livelihood, social undertakings and ecological construction. (Fan Xiaojian b, 2012)

5.2. Specific Targets

The Chinese government has developed specific targets to achieve the "Outline" and implement it in two phases. From present to 2015, our targets are as follows: Creating one income increasing project for one household. We should provide safe drinking water to all poor rural areas, electricity to all administrative villages, and remarkably reduce the population with no access to electricity in remote western regions and ethnic minority areas. We should increase the proportion of poor counties with high-grade highway above second grade, and build asphalt (cement) roads for 80% of the western administrative villages except in Tibet, so as to steadily improve the rural bus accessibility rate. We should increase gross enrolment rate for pre-school education and consolidate the achievement of nine-year compulsory education. We should also increase the gross enrollment rate in upper-secondary education to 80% and eradicating illiteracy among youth and middle-aged people. Every town should have a government-run hospital, and each administrative village has a health clinic. The participation rate of the new rural cooperative medical insurance remains stable at 90 %, and a general practitioner should be in place in each township hospital. The broadcast and TV should be provided to every household with each county having a digital cinema and each administrative village at least showing 1movie per month. Broadband should be provided to all administrative villages, and villages and traffic trunk lines should be covered by communication signals. By 2015, we would further improve the rural minimum living allowance system, the "five guarantees" system and temporary assistance system to achieve full coverage of the new rural old age insurance system.

The second phase of the "Outline" is from 2016 to 2020. The specific objectives are as follows. (1) To further guarantee safe drinking water in rural areas and improve tap-water accessibility. (2) To complete the renovation of dilapidated buildings for 8 million rural needy families. (3) To eliminate electricity problem throughout China. (4) To build asphalt (cement) roads for eligible villages, harden the roads in villages, provide shuffle bus for every village and improve the level of road service and the ability to prevent and fight disasters in rural areas. By 2020, we should basically realize the universalization of pre-school education and high school education, and accelerate the development of distance education and community education. People in poor areas should have equal access to public health and basic medical services. Radio and television are provided to every household and villages are basically covered by broadband. Improve rural public cultural service system, and basically guarantee that each national key county enjoys libraries, cultural centers, and township cultural stations. We should guarantee administrative villages have cultural activity centers.

5.3 Poverty Reduction Policies in the New Era

To achieve these goals, we need strong policies. Compared to the previous decade, the rural poverty reduction policy in the next decade will have the following characteristics.

First, the government should establish an overall pattern for poverty reduction. China should give more institutional arrangements and policy guarantees in fiscal support, investment, financial services, and personnel security. All sectors and departments should work out clear tasks and specific indicators to constraint them, so as to form a joint force to promote development in poor areas. A poverty reduction pattern is being put in place that embraces regional policies, industry policies and social policies. The Outline also stipulates that a poverty impact assessment should be conducted if there is any policy or project that would affect poverty reduction.

Second, for taxation policy, the central and local governments should gradually increase investment in poverty reduction and development. The newly added fund is mainly allocated to underdeveloped regions with special difficulties that lie in vast and contiguous stretches. Increase the transfer payments from central and provincial finances for poverty-stricken areas. We should exempt tariffs, pursuant to law, for programs attracting investment from home and abroad, premium projects invested by foreign countries, imported equipment for manufacturing our own products, and imported technologies, accessories and spare parts. We should deduct corporate donations for poverty reduction before we calculate income tax.

Third, as for investment policy, the government should increase input in infrastructure, ecological environment and livelihood projects. We should give more support in building road for villages; comprehensively develop agriculture, and support land remediation, improvement of small river basins, soil erosion control, and rural hydropower construction. The government should cancel the supporting funds below the county level for public construction projects such as ecological construction, providing safe drinking water in rural areas, and supporting the transformation of large and medium-sized irrigation areas.

Fourth, for financial services, the government should further improve policies for interest-discount loans for poverty reduction. We encourage small-sum loan on credit, continue to implement loan projects for disability rehabilitation, and realize full financial service coverage in certain towns and villages where those services are new to them. We should extensively expand fundraising channels for poor areas. We encourage and support corporate financial institutions to keep more than 70% of new funds for local use in poverty-stricken. We should actively develop rural insurance business and encourage insurance agency to establish grassroots service outlets in poor areas. We must improve the central financial subsidies to agricultural insurance premiums and encourage specialized agriculture insurances. At last, we should strengthen the rural credit system in poverty-stricken areas.

Fifth, for industrial policy, the government should implement all industrial policies for China’s western development project. National large-scale projects, key projects and emerging industries should be arranged to eligible poor areas. We should guide the transfer of labor-intensive industries to the poverty-stricken areas, support the rational exploitation of resources in poverty-stricken areas, and improve policy support for flagship industries with local characteristics.

Sixth, as for personnel policy, the government should organize personnel and volunteers engaged in education, science and technology, culture, and health service to work in poor areas and guide college graduates to start their own business there. We should make out incentive policies for cadres who have worked in poverty-stricken areas for a long time, and give preferential treatment of position, title, and other aspects for professional and technical personnel so as to bring into full play their role in poverty reduction and development. Moreover, the government should give more training for cadres in the poor areas and practical personnel in rural areas.

VI. Conclusions

To conduct poverty reduction program in China, a developing country with 1.3 billion people, is bound to encounter many difficulties. Although the Chinese government has made great efforts in eradicating poverty, China is a developing country with low income and facing big challenges in social development. The deep-seated problems hindering China’s development are yet to be addressed. Therefore, we have a long way to go in poverty reduction.

In the new historical era, the Chinese government will adhere to the scientific outlook on development, pursue inclusive development and put development-oriented poverty reduction at the top of our agenda. The Outline for Development-oriented Poverty Reduction for China’s Rural Areas (2011-2020) has made new policy targets: consolidate our achievements, help people shake off poverty and get well-off more quickly, improve ecological environment of the poor areas, increase their development capacity, narrow the development gap, and advance poverty reduction to a high level. All these lay a solid policy foundation and provide a macroeconomic environment for our poverty reduction efforts. As a developing big country, China should actively participate in the international poverty reduction programs, learn from other countries’ advanced knowledge and experience, and deepen international exchanges and cooperation. China should make great effort to work with the international community in order to build a better world which will enjoy common prosperity and free from poverty.

References

Fan Xiaojian a, “Fan Xiaojian’s Remarks on Challenges of Poverty Reduction”, China Daily,2012-8-13 13.