2012-China-ASEAN Forum Report2

Measuring Poverty & Well-being

When we start to consider the concept of ethnic minorities in a region as large and diverse as Southeast Asia and China, the differences across and amongst groups are so large as almost to render the category meaningless. There is a problem too with terminology; much of the discourse on ethnic groups in the region, and globally, is couched in the language of indigeneity. Thus groups identifiable as ethnically distinct from the majority ethnic group are often defined (or self-defined) as ‘indigenous people. To further compound the problem, there is no established definition in international law of either indigenous peoples or ethnic minorities, so the whole discussion is shrouded in uncertainty requiring some initial conceptual clarity and definition in order to render the subject intelligible. In this section we will therefore first attempt to define theterms we use, and justify our preference for the use of the term ethnic minorities throughout this paper.We will also show why a focus on these groups as distinct is valid and useful, through defining the common characteristics they share across the region. Finally, we discuss some issues in both conceptualising and measuring ethnic minority well-being.

2.1 The Use of ‘Ethnic Minority’ as a Classificatory Category in the Southeast Asia Region

Use of the classificatory categories ‘ethnic minorities’ and ‘indigenous people’ is ultimately conditioned by the political positioning of those who are using the terms. Broadly speaking, state governments in the Southeast Asia region, and China, prefer to use the term ethnic minorities when referring to culturally, linguistically and ethnically divergent groups living within the boundaries of the state as the term recognises their difference, whilst simultaneously reinforcing the notion that they are national citizens within one unified territorial nation state. In contrast, the concept of indigenous people has a strong political resonance which actively emphasises aspects of political mobilisation and organisation.

The concept of indigeneity is most often used by indigenous movements, collectively organisingto take action on representation and issues of social development. There are many examples in the region of self-defined indigenous groups, advocating for indigenous rights. Essentially then, as Levi and Maybury-Lewis argue, indigeneity is both a political moment and movement, not an anthropological category. (Levi and Maybury-Lewis, 2012). The use of indigenous peoples as a classificatory category is most prevalent in industrialised countries with mature plural, democratic political systems. But whether the term ethnic minority or indigenous people is used is largely a reflection of the positioning of those who are making the classification, and both those termed ethnic minorities and indigenous people share common characteristics across the Southeast Asian region. For the purposes of this paper, we shall use the term ethnic minorities in preference to the term indigenous people, as the paper is oriented towards policy changes and innovations that national governments in the region can make to improve the choices and opportunities open to ethnic minorities living within the boundaries of their nation states. In preferring the term ethnic minorities over indigenous people, however, it is emphasised that this is simply a classificatory choice and that both terms could be used to refer to essentially the same group of people in the region.

There is no legally binding definition of what it is to be ‘indigenous’ from any of the United Nations (UN) agencies, despite the existence of a number of fora, declarations and agencies specifically set up to promote and protect the rights of indigenous peoples. Examples include the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the Regional Initiative on Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Development. In the case of defining what it is to be an ethnic minority, any group that is smaller than the dominant ethnic group of a country is, by definition, an ethnic minority. However, many ethnic groups in the region are fully assimilated within mainstream cultures and societies and enjoy standards of living at least as high as the majority ethnic groups. The Manchu in China, for example, are highly urbanised and well represented in professional and other occupational categories; similarly ethnic Chinese groups in urban centres of Viet Nam and Cambodia. Use of the term ethnic minorities in the Southeast Asia region and China therefore has a strong normative element when used in the context of socio-economic development, as referring to those groups that often have lower standards of well-being than majority ethnic groups or the population in general. Thus, as Levi and Maybury-Lewis observe, although identity has to do with notions of sameness, ‘it becomes salient, paradoxically, only through the recognition of difference’.(Levi and Maybury-Lewis, 2012, 75). Identification as an ethnic minority is clearly relational, in that groups are defined, and define themselves, largely against and in comparison to, those with whom they share a state or territory. Otherness in ethnic terms can also be an imposed condition or category from colonial states, so indigenous identity and organisation can usefully be thought of as both imposed and endogenously created in response to the nation state.

Levi and Mayburypromote the notion of indigenous people as a ‘polythetic class’, whereby a number of common characteristics are shared across the group, but not all are necessary for inclusion in that group. (Levi and Maybury-Lewis, 2012).This fits well as a description of ethnic minorities, in that the identifiers that are often cited for ethnic minorities in the region are widely shared, though not necessarily universal for all; they have a relatively low economic standing, often live in upland or difficult areas, have been or are subject to structural dislocation, have a cultural distinctiveness, and a rootedness to land, amongst other characteristics. The UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues has adopted a pragmatic working definition for indigenous peoples, which also fits neatly in defining ethnic minorities within this notion of a polythetic class, as based upon:

‘self-identification as indigenous peoples at the individual level and accepted by the community as their member; historical continuity with precolonial and/or pre-settler societies; strong link to territories and surrounding natural resources; distinct social, economic or political systems; distinct language, culture and beliefs; and the fact that they form nondominant groups of society, and resolve to maintain and reproduce their ancestral environments and systems as distinctive peoples and communities.’ (Quoted in Hall &Patrinos 2012, 12)

It is important to recognise that there are also significant differences withinethnic minority groups too, not just between them. There is a tendency to speak of ethnic minority ‘groups’, rather than individuals, but as Levi and Maybury-Lewis notethis ‘has the unfortunate effect of eliding cross-cutting hierarchies of knowledge, gender, age, geography, and class that increasingly stratify indigenous peoples throughout the world.’ (Levi and Maybury-Lewis, 2012,80) Different cultures and societies in the region have different forms of organisation, some hierarchical, others less so, which reflects in how gender relations and generational relations are conducted, for example. Ethnic minorities are subject to globalising forces in the region too; they are not immune from the powerful transformative processes of economic and social development and cultural change that have swept through the ASEAN region, and China.Attempts to sentimentalise and essentialise ethnic minorities should therefore be resisted; ethnic minorities are no more likely to have ‘unchanging traditions’ or ‘pristine traditional societies’ than majority ethnic groups in the region. Rather, constant flux and change is the norm for all, and groups in the region are constantly negotiating the terms of their accommodation and engagement with the state, and with modernity.

2.2 Problems Inherent in Measuringand Defining Ethnic Minority Development

Both ethnic minority ‘poverty’ and ‘development’ are complex concepts which need to be clearly defined. Poverty is often equated with a lack of development, and certainly ethnic minority groups across the region share a common experience of living in poverty, as it is commonly perceived and measured. Poverty as a lack of income, or a lack of ability to consume in monetary terms, is how poverty is often conceptualised in the first instance by both international development agencies and national governments. Certainly according to narrow monetary definitions of poverty, ethnic minorities across the region are poor both in absolute terms, (i.e. in not reaching prescribed benchmark indicators of income such as the national poverty line in each country, or the international poverty lines of two and one dollar a day) and in relative terms (of being income or consumption poor in comparison to the average for the country as a whole, or in comparison to the majority ethnic group).

Poverty can also be defined and understood in other ways too, beyond monetary income and consumption terms. Some common alternative measures are capability poverty, where people may have a deficit in whatAmartyaSen describes as ‘the ability to achieve certain minimal or basic capabilities’ (Sen, 1993); social exclusion, whereby the poor are subject to certain processes of marginalisation and deprivation within society; and participatory approaches to defining poverty, which use poor people’s own understanding of deprivation to define poverty. (Stewart et al. 2003). Different approaches to theorising and measuring poverty privilege different dimensions of what is a complex and multi-faceted phenomena, and the approach to defining and measuring poverty is strongly conditioned by our normative understanding of what constitutes a good life, or well-being. Different ways of measuring poverty will also identify different groups of people as being poor. As Stewart et al. show, one measure of poverty can identify a completely different group of people as being poorfrom another poverty classifier, with the consequence that a group may be poor according to one measure, but not another.

Many definitions of poverty prescribe what particular groups are ‘lacking’ independent of what they themselves may consider to be important in constituting a good life. Many of the attributes of modernity, for example, such as a telephone connection, or a particular material for house construction, may not accord with ethnic minority cultural values or priorities. This extends to income, when ethnic minority groups may still rely heavily upon home production for consumption and upon networks of exchange in kind and kinship group reciprocity for meeting daily needs. Ethnic minority development is not, then, simply addressing a lack of modernity. Participatory approaches are important in this regard as they enable ethnic groups themselves to define what it is they consider important for well-being. With participatory approaches though, state development planners face the problem of aggregating the different dimensions of poverty identified into a coherent plan that can be applied across a broad area, and which can encompass a large number of people in a way that takes advantage of economies of scale. There is always a tension inherent, then, in participatory approaches, between locally responsive poverty reduction approaches and state planners need to deliver solutions at scale.

Certainly there are a number of indicators of human development that can plausibly be considered ‘universal’ in the sense that they would be prioritised by all. These include reducing infant and maternal mortality, life expectancy, improving literacy and school participation. However, even when there is agreement about the ‘ends’ for ethnic minority development, there is not necessarily agreement over the ‘means’ through which these outcomes should be delivered. Should state health services be directed, for example, at getting more women to attend state health clinics, or to promote better training for ethnic minority health extension workers that can work in ethnic minority villages? Should educational initiatives concentrate upon intensively exposing ethnic minority children to the majority state language, or should bilingual educational approaches be applied, gradually increasing children’s competency in majority languages whilst also developing their cognitive skills through instruction in their mother tongue? How far should state educational services concentrate upon the promotion of ethnic minority languages, if for example ethnic minorities themselves define this as an important part of increased wellbeing? Dilemmas such as these make the delivery of poverty reduction measures and the promotion of improved well-being challenging and highly contested, even when there is broad agreement about the ends to which development initiatives should be oriented.

Another problem lies in generating adequate information and data about ethnic minority development, to inform good policy making. Ethnic minorities often live in remote and difficult to access areas where data is not easily collected, and the dispersed nature of ethnic minority settlement means they are not often well represented in national data sets. Consequently there is a lack of good statistical data disaggregated by ethnicity in the region. The kinds of data and information collected about ethnic minorities is also often not adequate for understanding their livelihoods and cultural practices as it is data used to measure well-being in urban, mainstream society. It therefore reinforces perceptions of ethnic minorities as being ‘backward’ and ‘unmodern’, and does not further understanding of ethnic minorities’ distinct practices and development priorities. Censuses and other data collection methods often underestimate ethnic minority populations because of both their mobility as swidden cultivators and their relative isolation, and there are very few comprehensive data sources with high ethnic minority coverage.

In conclusion to this section, we can see that measuring poverty and defining development are highly problematic and contested endeavours. Who defines what is desirable in terms of improved well-being, what measures are used, and how solutions can be effectively and efficiently delivered, are all challenges which ASEAN state’s in the region, and China, continue to struggle with. Ultimately the choice of approach and indicators against which to measure progress reflects our normative understanding of what constitutes wellbeing. Whilst there are a number of goals which are undoubtedly shared by all parties to the development process, ultimately the long term success of promoting development for ethnic minorities must be predicated on a participatory approach, with ethnic minorities themselves defining both what is desirable in terms of improved wellbeing, and how these goals can best be achieved. Such a participatory approach relies upon states in the region accepting and recognising the notion of diversity in society.Recognition of diversity can make society stronger, more harmonious and more secure, and make development oriented interventions by the state more sustainable.

3. Country Situation Analysis:Ethnic Minority Povertyand Country Specific Policy Responses

3.1 China

Demographic and Population Trends

China’s ethnic minority population dwarves that of any other state in the region, and the experience of being an ethnic minority in such a large state is correspondingly diverse, with ethnic minority groups as diverse as the Uighurs in the far west, the Miao/ Hmong in the south west and the more cosmopolitan, urban based Manchu all co-existing under the term ‘ethnic minority’. For some ethnic minorities, such as the Tibetans and Uighurs for example, they can also constitute a majority group in their regions. The Chinese government officially recognises 55 ethnic minority nationalities and, according to the last census in 2010, the total ethnic minority population comprises 113.9 million people from a total national population of 13 billion, so approximately 8.5 percent of the population. Peters points out, though, that the official classification of ethnic minorities into these groups could be misleading, making it hard to see the considerable diversity that also exists within these groups. (Peters, UNDP, 2012). Table 1 gives indicative figures for ethnic groups in China, as a percentage of the total population (2010 census figures).

Table 1: Ethnic Groups in China as a Percentage of the Total National Population (2010)

|

Han |

91.51% |

Others |

1.47% |

Korean |

0.14% |

|

Chuang |

1.27% |

Tuchia |

0.63% |

Pai |

0.15% |

|

Manchu |

0.78% |

Mongolian |

0.45% |

Hani |

0.12% |

|

Hui |

0.79% |

Tibetan |

0.47% |

Kazak |

0.11% |

|

Miao |

0.71% |

Puyi |

0.22% |

Tai |

0.09% |

|

Uighur |

0.76% |

Tung |

0.22% |

Li |

0.11% |

Source: 2010 Population Census Data, National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS)

http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm

The officially designated ethnic minority population actually grew from 5.8 percent in the 1964 census to 8 percentby 2000, a phenomenon Hoddie and Gladneyattribute to an increase in the range of state benefits available to ethnic minorities in the period following the Cultural Revolution, such as exemption from the one child policy, which resulted in more groups accentuating their difference and distinctiveness in ethnic terms. Jean Michaud has also shown that many ethnic groups in China today are not indigenous to the areas in which they currently live, further complicating the picture of what it means to be an ethnic minority in China today.(Referenced in Hannum and Wang, 2012).As with ethnic minorities throughout the region, many ethnic minority groups in China live in border regions that are considered strategic and sensitive, and in areas with significant endowments of natural resources, such as oil, gas, coal and hydropower.

Features of Ethnic Minority Poverty

China’s impressive poverty reduction record is well known, and perhaps historically unprecedented. Using China’s own official poverty standard, the (headcount) poverty ratio in rural China fell from 18.5 percent in 1981 to just 2.8 percent in 2004. This meant the number of rural poor declined from 152 million people to 26 million. Using the World Bank poverty standard for the same period (1981-2004) the percentage of those consuming below the poverty line fell from 65 percent to just 10percent, and the absolute number of poor people fell from 652 million to 135 million. (All figures from World Bank 2009).

Poverty reduction and development in general has been uneven in China, however. Gini, a measure of inequality, rose from 30.9 percent in 1981 to 45.3 percent in 2003 (World Bank 2009). Economic development has been spatially concentrated, with urban centres and the booming eastern seaboard regions galloping ahead of the rural hinterlands, the areas where most ethnic minority people live. Between 1989 and 2004 for example, coastal incomes tripled whilst inland incomes only doubled, so that by 2004 the mean per capita household income of inland provinces was barely two thirds that of coastal provinces. Poverty remains most sever in these upland, ethnic minority areas, with poverty reduction having taken place much faster in the coastal regions.In 2009, over 54 percent of those classified as being poor lived in ethnic minority areas. Table 2 below shows how both differences in urban-rural income and majority-minority ethnic group income are substantial. Significant poverty reduction and economic development have taken place in rural, ethnic minority areas, but at nowhere near the same pace as for lowland coastal regions so that, in relative terms, ethnic minorities constitute an increasing share of the rural poor, even if the absolute numbers of poorpeople are shrinking.

Table 2: Average Income of the Adult Population by Ethnic Group, 2005

|

|

Monthly income (Yuan) |

||

|

Ethnic Group |

Urban |

Rural |

Total |

|

Han |

842 |

386 |

574 |

|

Zhuang |

604 |

266 |

359 |

|

Manchu |

793 |

390 |

545 |

|

Hui |

806 |

319 |

550 |

|

Miao |

639 |

253 |

313 |

|

Uygur |

693 |

236 |

310 |

|

Other minorities |

714 |

282 |

367 |

|

|

As a Percentage of Corresponding Han Income |

||

|

Zhuang |

72 |

69 |

63 |

|

Manchu |

94 |

101 |

95 |

|

Hui |

96 |

83 |

96 |

|

Miao |

76 |

66 |

55 |

|

Uygur |

82 |

61 |

54 |

|

Other minorities |

85 |

73 |

64 |

Source: 2005 mid-censal survey, (quoted in Hannum and Wang 2012, 174.)

Geography clearly plays an important role in explaining patterns of ethnic disadvantage in China, across all indicators of well-being. Poverty is overwhelmingly concentrated in the western interior regions, with average incomes much lower and indicators of human development (such as health and education) also lower in comparison to cities and regions of the coast. Although regional unevenness is certainly a powerful driver of ethnic minority poverty, the trend is not just spatial. There are also clear differences related specifically to ethnic minorities versus majority groups in rural areas too; ethnic minorities are one and a half to two times more likely to experience poverty than their Han (majority) counterparts. More than one in ten rural minority children are below the national poverty line, compared to one in twenty five rural Han children, and the rural income of ethnic minority children is only slightly less than two thirds on average that of rural majority children. In rural areas minorities have less access to wage employment than the Han and make less money when they do engage in wage employment. Overall, ethnic minority household income is significantly lower in rural areas than for the ethnic majority. (Hannum and Wang, 2012).

These trends do not just relate to income either, but to a range of broader indicators of human development. In education for example, whilst all groups have experienced educational expansion in recent decades there are clear disparities in attainment and enrolment amongst school aged children, with ethnic minority children significantly over represented amongst those who are excluded from compulsory schooling.Despite the expansion of the school system, ethnic minority youth are more likely than their majority counterparts to continue to be unable to access compulsory education. (Hannum and Wang, 2012). In terms of health, although the data available is scarce, regional studies show that ethnic minority areas continue to have less developed health care infrastructure, that health care access for ethnic minorities is a problem, infant mortality rates are higher for ethnic minorities in Yunnan province, and ethnic minorities are over-represented amongst those affected by HIV/AIDS, with the ethnic minority areas of Yunnan, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region particularly hard hit.Ethnic minorities are also generally under-represented in professional, clerical and managerial jobs, in party positions, and are over represented in agriculture.

As with elsewhere in the region, years of educational attainment is closely tied to future earning prospects, and this is increasingly the case as the importance of industrial and service sector employment increases. Education is therefore a critical factor in determining whether ethnic minority workers from the rural areas in which they overwhelmingly live are able to find urban jobs and thus a pathway out of poverty. Overall, ethnic minority children are about a half year behind Han children in school attainment and are less likely to have made the transition to junior high school. In 2002, 431 counties had not yet made the nine year compulsory education cycle universal:372 of these counties were in the western region, and 83 percent of these were counties where predominately ethnic minorities lived.Hannum and Wang conclude:

‘whereas the absolute level of exclusion has dropped precipitously among minorities, their relative vulnerability to exclusion has intensified as exclusion has dropped even faster among non-minorities. In 1990, minorities were about 1.5 times as likely as Han to be excluded. By 2005, they were about 3.8 times as likely as Han to be excluded.’ (Hannum and Wang, 2012, 183).

Those excluded from education are now much more likely to be dissimilar from the general population: to be poorer, to live in hard to reach areas, and to be members of ethnic minority groups. Factors driving the poorer participation of ethnic minorities in education include household financial restraints, problems of recruiting and retaining staff in remote areas, and in some cases a lack of ability in the majority language on the part of ethnic minority children, with little flexibility in the education system for bilingual education for minorities in the early years of schooling. Less urbanised ethnic groups also have less access to important safety nets, such as unemployment and pension insurance, or health insurance, as good quality insurance is closely tied to urban residence.

Government Responses to Foster Ethnic Minority Development

The principles of ethnic unity and the diversity of China as a multi-ethnic state are embodied in many state documents, such as the Law of Regional Ethnic Autonomy (1984, 2001) and the 2009 State Council White Paper on Ethnic Policies. Integration and co-existence between the majority and ethnic minorities figure as prominent themes in state documents over the past sixty years since the founding of the People’s Republic and regional autonomy is a key feature of the administrative organisation of the state in China, with autonomy extended through all levels of the system. At the highest level, there are five autonomous regions with the right to limited self-government, including in passing legislation, promoting economic development, the control of local finances, and the training of ethnic minority cadre. There are also thirty autonomous prefectures and 120 autonomous counties with the authority to establish development initiatives specifically tailored to local ethnic minority needs, within the national framework. As early as 1949 a specific state body responsible for ethnic minority affairs was established, the State Ethnic Affairs Commission (SEAC) with a specific brief to direct public affairs in relation to ethnic minorities.

Along with the development of autonomous ethnic minority areas, there are also laws designed to specifically promote the interests of ethnic minority groups and to respect cultural traditions, as for example in the exclusion of ethnic minorities from the state’s one child family planning policy, and in promoting ethnic minority access to education.There are also twelve national ethnic minority educational institutes and one national ethnic minority university exclusively for the education of minority students. As Peters (UNDP 2012) and others note, however, there are still barriers to the implementation of a system of bilingual education within the formal state schooling system, despite some innovative and highly successful examples of bilingual education initiatives at the local level, which have demonstrated significant success in improving ethnic minority participation and educational achievement. Language barriers in educationrepresent one of the most significant restraints to promoting ethnic minority socio-economic development and participation in national life.

Attention and financial resources have also been allocated to specific poverty reduction policies, plans and programmes which are targeted at ethnic minority areas. The State launched the Western Development Strategy in 2000 as a means of focusing policy attention and resources upon the poorer western region of the country, and regional targeting has been the prevalent model for poverty reduction, at township level and increasingly village level after 2001.Ethnic minority areas are clearly favoured in the process of allocating regional resources to poor areas, with ethnic minority countiesoften included in the poor counties list even when they do not meet objectively measured poverty criteria. Ethnic minority counties consequently made up almost half of the total poor counties in 2001. Specific funding is provided too through initiatives like the ‘Ethnic Minority Development Fund’ and tax concessions are given to businesses to set up in ethnic minority areas too under ten year development plans.

However, the World Bank’s 2009 Poverty Assessment recognised the need to shift, in coming years, from ‘poor areas to poor people’. This is a recognition of China’s success in poverty reduction to date, meaning increasingly that poor people live amongst those who are better-off, and consequently poverty reduction funds delivered through area based programmes may benefit the non-poor as much as the poor. There is an increasing recognition too that, in the case of ethnic minority poverty, those who are poor may now require more nuanced, tailored approaches to poverty reduction reflecting the difficulty of addressing poverty factors that have proved resilient to date. The extension of the Di Baosocial welfare system from urban to rural areas of China is a welcome development in this regard. Poverty for ethnic minorities may not be so easily solved using past methods, such as infrastructure provision for example, as the causes of continuing poverty are more complex, with multiple drivers of disadvantage such as remoteness, lack of household assets, social exclusion, poor education and poor health. Such diverse and complex causes require similarly multi-dimensional, tailored solution which are not easily developed or provided en masse.

3.2 Lao PDR

Demographic and Population Trends

Laos has arguably the most ethnically diverse population of any of the states in Southeast Asia. Within a population of five million people, nearly one third are commonly classified as ethnic minorities. The population can be divided into four broad ethnic linguistic categories; the Lao-Tai (67 percent of the population), the Mon-Khmer (21 percent), the Hmong –Lu Mien (8 percent) and the Chine-Tibetan (3 percent). (King and van de Walle, 2012, pg. 249). Within this classification, there are an estimated 49 distinct ethnicities and a further 200 ethnic sub-groups. The primary political division until the early 1980’s, however, was into three groups: the Lao Lum (lowlanders), Lao Thoeng(midlanders or uplanders), and Lao Sung (highlanders). Although these classifications are no longer made in official discourse, they correspond in many ways to the profile of relative socio-economic development of different ethnic groups with the lowland Lao-Thai, the majority ethnic group, generally better off and living in the densely populated and fertile lowland areas and urban centres. The Mon-Khmer people typically live in midland rural areas in the north and south, and the Hmong-Lu Mien reside in the mountainous northern highlands and are significantly more disadvantaged in material and human development terms.

Features of Ethnic Minority Poverty

Laos is amongst the poorest countries in Southeast Asia, with almost a third of the population classified as being poor in 2002-2003. There is a significant difference between the majority Lao-Thai group and ethnic minorities, with ethnic minorities twice as likely overall to be poor (50.6 percent) than the majority (25 percent). (All figures from King and van de Walle, 2012). The pattern of ethnic minority disadvantage in relation to the ethnic majority is replicated in non-income measures of well-being too:Lao-Thai heads of household have more average years of education (5.4 years) than their ethnic minority counterparts (2.9 years), and majority villages have better access to social and economic infrastructure such as electricity, schools and health posts. They have higher consumption levels overall, and are more likely to benefit from remittances. (All figures from King and van de Walle, 2012). Economic analysis suggests that the benefits of better endowments for ethnic majority households are mutually reinforcing: households with better endowments have higher incomes, and are thus more likely to invest in education. Conversely, ethnic minorities lack the endowments to break inter-generational cycles of poverty. They have on average less productive agricultural land, are less integrated into commercial agricultural networks, and are more likely to rely upon forest products than the majority Lao-Thai groups. They are also far less likely to be engaged in non-agricultural economic activities. Table 3 summarises poverty by ethnicity and region in 2002-2003.

Education in particular is a significant factor in ethnic minority children’s disadvantage: they are more likely than majority children to be enrolled in school at a lower grade than their age, and school enrolment falls sharply after the primary school cycle. Educational inequalities between ethnic minorities and the majority Lao-Thai group appear to be driven by many different factors. Certainly the relatively poor quality of educational infrastructure in highland areas is a significant contributing factor, as is the difficulty of recruiting and retaining well qualified staff to teach in minority areas, and competing pressures upon ethnic minority households for children to contribute to the household economy, through agricultural labour. The significant distances that ethnic minority children have to travel in order to access education is also a significant barrier, as is the practice of teaching children in multi-grade classrooms. Ethnic minority children in upland areas are more likely to be taught by ethnic minority teachers, but these teachers are less likely to have the same level of qualifications as their lowland, majority counterparts, suggesting there may also be gaps in the quality of education received by ethnic minority children, though lessons are more likely to be delivered in ethnic minority languages. There is a significant gap in ethnic minority girl’s educational participation in comparison to boys too and this carries through to adult life, with ethnic minority women and children having by far the worst indicators of human development of any group in Laos.

Table 3: Poverty by Ethnicity and Elevation, 2002-03

|

|

Total |

Rural |

||||

|

Lao-Tai |

Non Lao-Tai |

Total |

Lao-Tai |

Non Lao-Tai |

Total |

|

|

Total Poverty headcount (%) |

24.97 |

50.62 |

33.56 |

28.60 |

51.13 |

37.71 |

|

Lowlands Poverty headcount (%) |

23.83 |

52.56 |

28.18 |

28.42 |

55.07 |

33.62 |

|

Midlands Poverty headcount (%) |

27.96 |

51.13 |

36.48 |

28.11 |

49.44 |

36.24 |

|

Highlands Poverty headcount (%) |

28.33 |

49.51 |

43.91 |

30.27 |

50.01 |

45.17 |

Source, LECS 2002-2003, adapted from King and van de Walle, 2012, pg. 254.

In terms of illness and the utilisation of health services, there are significant inequalities apparent between the majority Lao-Thai group and other ethnic minorities. Survey data shows that Lao-Thai men and women are much more likely to seek treatment at a health care facility when sick than ethnic minorities, which reflects the relative lack of available services in ethnic minority areas, the difficulty of accessing services, and perhaps a propensity for ethnic minorities to be less willing to attend Government health service facilities where they exist. This may be because of cultural alternatives to formal treatment that exist within ethnic minority communities, but may also result from the costs associated with travel and payments required for treatment and medicine, or discrimination that ethnic minorities face in accessing services in towns.

Government Responses to Foster Ethnic Minority Development

The challenges in promoting ethnic minority poverty reduction and development in Laos are significant, with interlocking factors compounding disadvantage across generations. One approach to addressing spatial and ethnic differences adopted by the Lao government has been the development of assimilationist schemes of resettlement of upland and highland people. Resettlement schemes have focused upon establishing resettlement centres in lowland areas, where it is felt that state services can be delivered more effectively and efficiently to ethnic minority people. These schemes have also emphasised wetland rice cultivation, a system of agriculture not traditionally practiced by many upland minority groups. Consequently the impact of these schemes on poverty reduction has not been clear andthey have often resulted in conflicts with lowlanders already living in the resettlement zones. Critics of these schemes have also drawn attention to thesignificant costs to ethnic minority people’s cultural wellbeing, with resettlement resulting in the disconnection of ethnic minority people from ancestral lands and livelihood practices. (Baird and Shoemaker, 2007).For many upland groups, ethnic identity is intimately connected to the lands in which they live, and the cultural and livelihood practices that they have developed in these locations over many generations. Shifting to a new agro-ecological zone means abandoning many of the practices with which ethnic minorities are familiar and attempting to adopt unfamiliar new livelihood practices, which can have calamitous results for ethnic minority well-being and cultural survival.

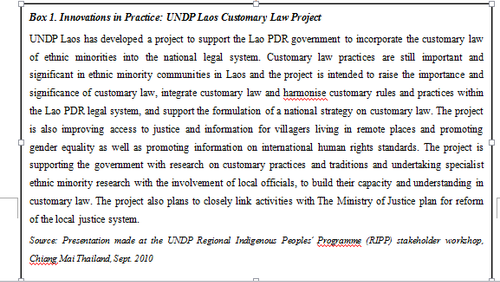

The Lao Government in 2003 initiated a program targeting support to 72 priority districts considered to be the poorest out of the total of 143 districts in the country. Targeted support to ethnic minority areas is likely to be most successful when plans are tailored to the specific needs of ethnic minority groups, where they build upon the significant upland experience of these groups and where they encourage a high degree of participation by ethnic minority groups themselves in defining development solutions. The complex pattern of ethnic minority disadvantage in Laos requires correspondingly multi-dimensional solutions, with ethnic minority human resource development (particularly better health and education) clearly a priority need.

3.3 VIETNAM

Demographic and Population Trends

Viet Nam’s ethnic minority population makes up approximately 14.5 percent of the total population of 86 million people, so an estimated 12.5 million people. State classifications of ethnic minorities recognise 54 groups, including the majority Kinh ethnic group, though within these recognised ethnic minority categories there is considerable ethnic diversity too. Viet Nam’s ethnic minorities live predominately in upland or remote areas close to Viet Nam’s borders and for many groups, such and the Khmer or Hmong for example, there are also significant populations living in neighbouring countries too. When comparing majority and ethnic minority groups the Chinese in Viet Nam, the Hoa, are usually included with the majority group as they enjoy average incomes and human development indicators at least as high as the majority ethnic group, and they are predominantly urban residents with a similar occupational profile to the urban majority ethnic group. In contrast other ethnic minority groups are primarily rural residents and engaged principally in agriculture as the primary form of occupation, either as farmers or farm labourers.

In 2006, over 70 percent of ethnic minorities lived in the mainly mountainous regions of the northeast and northwest, and in the central highlands. The other major area of ethnic minority settlement is in the remoter parts of the Mekong delta, where large numbers of the Khmer live. In contrast, nearly two thirds of the majority ethnic group (64 percent) live in the lowland south east or the two densely populateddelta regions of the Red River in the north and the Mekong delta in the south. (Dang, 2012). Ethnic minorities on average have a younger age profile to the household, and live in larger households with a higher care burden in terms of both small children and older people. Some basic demographic comparisons between ethnic majority and ethnic minority households are included in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Viet Nam Basic Demographics, 1998-2006

|

|

Ethnic Minority |

Ethnic Majority |

Total Population |

|||

|

|

1998 |

2006 |

1998 |

2006 |

1998 |

2006 |

|

Male (percentage) |

49.2 |

49.7 |

48.3 |

48.9 |

48.5 |

49.0 |

|

Average Age |

25.2 |

27.0 |

28.7 |

32.1 |

28.2 |

31.4 |

|

Married (15 years and over) (percentage) |

63.2 |

65.0 |

59.1 |

60.5 |

59.7 |

61.1 |

|

Household size |

6.1 |

5.8 |

5.4 |

4.7 |

5.5 |

4.9 |

|

Urban (percentage) |

1.6 |

7.4 |

25.9 |

29.8 |

22.5 |

26.7 |

Source: Adapted from Dang 2012, 311. (Calculated from Vietnam Living Standards Surveys 1998 and 2006)

Features of Ethnic Minority Poverty

Poverty in Viet Nam is increasingly an ethnic phenomenon. Although ethnic minorities account for only 14 percent of the population, they accounted for over half of the total poor in 2008, up from 18 percent in 1993. The reason for this is simple. Poverty amongst ethnic minorities has declined over the past 15 years but the rate of decline has been much faster for the majority ethnic group (and the Hoa) so that ethnic minorities represent an increasing share in the remaining poverty population. Figure 1below shows this trend clearly. An estimated 72 percent of ethnic minorities fall into the poorest three consumption deciles of the population, i.e. the bottom 30 percent, and 88 percent are in the bottom 50 percent of the population for consumption. (Dang 2012, 310). Ethnic minorities are clearly much poorer then than the majority population in income and consumption terms.

Figure 1: Poverty Reduction for Majority and Ethnic Minority Groups, 1993-2008

Source: World Bank 2010 (Calculated from VLSS 1993, 1998; VHLSS 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008)

Income is not the only welfare measure that highlights ethnic minority poverty. In terms of landholding, ownership of assets and access to essential public goods and services such as clean water and electricity, ethnic minorities are also demonstrably lagging behind. Land is an interesting example. Survey data demonstrates that total landholdings for ethnic minorities are actually often larger than for the majority group. However, when the quality of land is examined, ethnic minorities are less likely to own the best quality land. They also own forestland, but hold this as custodians and are unable to exploit it fully for commercial gain.

Significant improvements have been made in the availability of basic infrastructure and public services for ethnic minorities in extremely difficult communes of the country. However, studies show that ethnic minorities tend to utilize both infrastructure and services less than their majority group neighbours. In terms of livelihoods, ethnic minorities are less integrated into commercial networks and less likely to produce the kind of cash crops or industrial crops that generate significant income. Integration into these kinds of commercial networks remains largely the domain of the majority ethnic group.

The gap in living standards and human development between different ethnic minority groups in Viet Nam is also widening, to the extent that some of the larger ethnic minority groups (such and the Tay, Thai, Muong and Khmer) are approaching the average level of income of the Kinh and Hoa majority. Smaller ethnic minority groups such as the H’re and Bana, and the large number of Hmong living in the northern uplands, are still in deep and chronic poverty, however. Table 5 provides poverty data for different ethnic groups based upon a large scale survey in ethnic minority areas carried out by the Government and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 2007. These clear differences in poverty between ethnic minority groups make both diagnostic and prescriptive inferences about ethnic minority poverty difficult. Size of group clearly matters, as many of the smallest ethnic groups are also the poorest, but how then to account for the Hmong, who are amongst the largest ethnic minority populations, but are also amongst the poorest.

Table 5: Poverty in Extremely Difficult Communes of Viet Nam, 2007 (Percentage Figures).

|

|

2005 poverty line, headcount index |

2007 Consumer Price Index (CPI) adjusted poverty headcount index |

|

Ethnic Groups |

||

|

Majority |

27.1 |

37.1 |

|

Ethnic Minorities |

50.3 |

60.9 |

|

Tay |

45.7 |

59.6 |

|

Thai |

49.1 |

57.5 |

|

Muong |

44.0 |

54.4 |

|

Nung |

51.3 |

59.8 |

|

Hmong |

73.8 |

82.6 |

|

Dao |

49.4 |

66.2 |

|

Others in Nth. Mountains |

51.2 |

62.1 |

|

Bana |

57.7 |

71.9 |

|

H’re |

60.8 |

73.6 |

|

Co Tu |

49.8 |

63.8 |

|

Others in C. Highlands |

61.6 |

71.5 |

|

Khmer |

28.4 |

34.7 |

|

Others |

57.1 |

68.9 |

|

Daily language |

||

|

No or little Vietnamese |

53.8 |

64.2 |

|

Both Vietnamese & ethnic lang. |

44.0 |

54.9 |

|

No or little ethnic language |

28.7 |

38.9 |

Source: Adapted from CEMA/ UNDP Programme 135 Poverty Report, 2011. (Data calculated by authors from the P135 baseline survey conducted in 400 poor communes of the country in 2007)

A significant causal factor behind poverty for ethnic minority groups that is apparent from both studies and survey data is that those who speak no or little Vietnamese are consistently poorer than those who do speak the majority language. This is evident from the data in the final section of Table 5 above. Dang calculates that the chances of a household being poor where the household head has no years of schooling is 52 percent, whilst the chance of being poor is only two percent where the head has 12 years of schooling. (Dang 2012, 317). Ethnic minorities have far lower educational attainment levels than the majority group and they are also far more likely to drop out of school. Reasons for this include being ‘over age’ and thus unwilling or unable to continue, and the need to work in order to support the economic or subsistence needs of the household. Poverty is therefore an important driver of low educational attainment, and a lack of education is a critical factor in perpetuating the inter-generational cycle of poverty amongst ethnic minority groups.

Less easy to quantify is the deficit ethnic minorities face in the quality of education and other services, but it is undoubtedly there, as many qualitative studies show. Ethnic minority schools don’t have the same learning materials and opportunities, have poorer quality teachers, and ethnic minority children travel further to get to school. In terms of health, ethnic minority children living in rural areas are 15 percent more likely not to be fully immunised, have lower health care expenditure and have fewer health care services available than in majority communes and villages. Infant and under five mortality rates are also higher, as is HIV/AIDS infection rates. (All figures from Dang 2012, estimated from VHLSS 2006). Ethnic minority women have the lowest health care expenditure of all, and are the poorest across a range of human development indicators.

In terms of healthcare coverage ethnic minorities have significantly benefitted from the Government’s provision of free health insurance and free health certificates under various poverty reduction and support programmes, with an estimated 70-80 percent of ethnic minorities covered by some form of health insurance or health certificate scheme. However, ethnic minorities are heavily reliant upon commune health services, which remain rudimentary, and the health coverage provided does not cover major health expenditures. Ethnic minorities are in any case often unable to meet the cost of travel and accommodation to district or other hospital facilities and are more likely to rely on alternative health care arrangements, such as practioners of traditional medicine.

How households diversify away from subsistence agriculture is the key determinant of their long term wellbeing. Ethnic minorities are twice as likely as majority groups to be working in agriculture, live in remote and mountainous communes, and are far less mobile and less integrated into labour markets than their majority neighbours. As they are more likely to be engaged in agriculture for subsistence, they are much less likely to be producing higher value cash crops, or industrial crops (such as rubber) for which the economic return is far higher. Forestry landholding amongst ethnic minorities is often significant, but forestry income contributes a very modest amount in total to household income. In terms of the income structure of the majority ethnic group, they are far more likely to beearning wages, benefiting from non-farm income or transfers, and much less likely than ethnic minorities to depend on income from crops and livestock. (CEMA/ UNDP 2011)

Ethnic minorities then face a range of interlinking factors compounding poverty. An inability to speak Vietnamese excludes ethnic minorities (and particularly ethnic minority women) from participating in market networks, accessing market information, and utilizing public services. They have poorer quality assets too: whilst ethnic minorities have land holdings that may exceed those of the majority group, the land is often poorer quality, non-irrigated land. Agricultural extension support services provided areoften not suitable for the particular environments in which ethnic minorities live. Similarly with the quality of education received, this may often be inferior in areas with a high concentration of ethnic minorities, where it is difficult to attract good teachers. Some cultural practices, like community levelling mechanisms and cultural perceptions of mutual social obligation may restrict opportunities for ethnic minority households to accumulate income. But even where ethnic minorities have the same education level as the majority ethnic group, studies suggest they receive significantly less wages than their majority counterparts. Finally, an important contributing factorlies in misconceptions and stereotyping of ethnic minorities. Although difficult to measure, the negative portrayal of ethnic minoritiesmay also contribute to reinforcing and perpetuating ethnic minority poverty.

Government Responses to Foster Ethnic Minority Development

The Government of Viet Nam has historically invested a great deal of political attention and financial resources to the issue of addressing socio-economic inequality amongst ethnic groups and promoting the development of the remote and upland areas in which ethnic minorities predominately live. There is a ministerial level agency, the Committee for Ethnic Minority Affairs (CEMA) which has responsibility for ethnic minority issues and CEMA has representation down to district level in those areas which have an ethnic minority population of more than 5,000 people, and in those areas considered geographically strategic. There have been a large number of policies and programmes developed for supporting ethnic minority poverty reduction and development, spanning the sectors of health, education, forestry, agriculture, labour export and culture. Along with regular policies of the Government to support ethnic minorities, the Government of Viet Nam has also developed a number of targeted poverty reduction programmes. One of these is specifically aimed at poverty reduction in ethnic minority communes, the so-called ‘Programme 135’, which was initiated in 1998 and had been progressively expanded to cover 1,848 of the poorest communes and 3,274 of the poorest villages nationwide by 2010. The programme is coordinated by CEMA at the national level and concentrates upon supporting infrastructure development in remote and mountainous communes and also provides support to agricultural development, livelihood activities and training for local people and officials.

The area based approach to poverty reduction was supplemented in 2009 with the development of a programme to support the 62 poorest districts of the country under Resolution 80a of the Government, again with significant funds allocated for infrastructure development. Many of the poor communes included under the programme 135 are also covered by Resolution 80a, and by another large national programme, the National Targeted Programme for Poverty Reduction (NTP-PR). Although targeted at all poor households and not specifically ethnic minorities, the NTP-PR does still support ethnic minority communities and households through providing such things as agricultural extension services, health insurance and health care cards, preferential credit funds and legal support services. Both resolution 80a and the NTP-PR are co-ordinated by the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MoLISA) at the national level. Other important programmes and policies for supporting ethnic minority communities include Decision 134 for support to land, housing and access to safe water supply, Decision 167 on providing housing assistance to the poor, and policies to provide aid for ethnic minority students, and the construction of boarding houses and provision of subsidies for ethnic minority students from remote areas. A range of policies also include clauses promoting the preferential treatment of ethnic minorities in accessing state services.

Although there is a proliferation of policies and programmes targeted at addressing ethnic minority poverty, the Government’s own reports suggest that there are significant gaps and problems in implementation (MoLISA/ CEMA/ UNDP 2004, 2009). One problem is the relatively low level of financial support provided through such policies, meaning households do not receive sufficient benefits to qualitatively affect well-being. The proliferation of policies and programmes also results in significant transaction costs for the local governments and officials tasked with implementing and administering the support. Because of the large number of policies and programmes and the wide range of ministries and agencies involved, poverty reduction support is often provided in an uncoordinated way, and support is not responsive to household and community needs, so that it either arrives late, or households qualify for one particular kind of assistance (housing support, for example) when they really need something else (such as preferential credit). Under the Vietnamese Government system there are few strong incentives for line ministries to work together and different agencies prefer to develop their own programmes, which complicates the task of providing coordinated and coherent poverty reduction planning and support. The Government of Viet Nam has recognised this problem and taken steps to address the issue through the recently passed Resolution 80 (2011) which provides an overarching framework for poverty reduction support in the country under one lead line ministry, MoLISA.

A further complication with Government programmes of support to ethnic minorities is the preference for providing area based solutions, and the high proportion of infrastructure support in programme portfolios. Government planners prefer area based solutions because they are seen as being more equitable, in that all residents of an area defined as poor receive support. The heavy preference for infrastructure investment further reinforces this, with infrastructure provision seen as being an investment form from which everyone benefits. However, studies increasingly show that many areas designated as ‘poor’ are in fact increasingly heterogeneous, with both poor and non-poor groups living in close proximity. Non-poor groups are thus just as likely to benefit from poverty reduction funds as the poor, with the level of inequality between majority and minority ethnic groups in Programme 135 communes, for example, actually higher than the rural national average (CEMA/ UNDP 2011). As poverty becomes less of a ‘mass based’ condition, then, more nuanced and better targeted solutions are required. This extends to the provision of infrastructure support too: certain kinds of infrastructure support are highly beneficial for poorer ethnic minorities, such as village level social infrastructure like schools and health posts, and farm to market roads. Larger scale infrastructure though, such as district centre to district centre highways, are likely to benefit traders and larger scale rice farmers, which in ethnic minority areas are usually members of the majority Kinh ethnic group.

Poverty reduction programmes in ethnic minority communes invest heavily in other aspects of the enabling environment too, such as providing price and transportation subsidies to businesses operating in ethnic minority areas, and supporting model demonstration farms. This means poverty reduction funds allocated to ethnic minority poverty reduction do not always go directly to ethnic minority households themselves. In the case of demonstration farms, they are often the farms of ethnic majority farmers, and the same is often the case for subsidised businesses.The large-scale poverty reduction programmes targeted at ethnic minority areas also face a dilemma in how to deliver targeted solutions appropriate to local poverty contexts, but in a coherent way that is manageable nationally and takes advantage of economies of scale. Increasingly, it is recognised that ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions may no longer be appropriate for tackling the entrenched poverty problems of particular ethnic groups.

4. Common Barriers to Ethnic Minority Development and Policy Gaps

Ethnic minorities across the region share common characteristics of disadvantage which lock communities and households into long term, chronic poverty. This disadvantage is perpetuated across generations in a cycle that becomes increasingly difficult to break. This section will first summarize the key common features of ethnic minority poverty that arise from the preceding country analyses, and attempt to summarize too the underlying causes driving ethnic minority disadvantage. In the second part of this section, we will consider the policy gaps that exist in addressing ethnic minority poverty.

4.1 The Key Features of Ethnic Minority Poverty in the Region, and Their Causes

Ethnic minorities across the region are vastly over-represented in the remaining pool of people who can be considered poor. Rural poverty reduction has been rapid and significant throughout the region, driven by the spectacular regional economic growth that has taken place. But this poverty reduction has largely benefitted those living in lowland rural areas, and those belonging to the majority ethnic groups of the region, rather than upland and remote ethnic minority groups. Although the total number of poor people in the region has fallen dramatically, the rate of decline for ethnic minorities has been much slower. They represent an increasing proportion of the remaining poor, with the consequence that the face of the rural poor is increasingly likely to be an ethnic minority face.

This situation is reflected in both monetary and non-monetary indicators. Ethnic minorities across the region have lower average per capita incomes than the national average, consume less, and generally have lower levels of human development. Life expectancy is lower for ethnic minorities, infant and maternal mortality higher, and ethnic minority children are less likely to complete the national average years of schooling. Ethnic minority people are more dependent upon agricultural production for subsistence, less integrated into commercial markets for cash crops, and are less likely to be engaged in off-farm labour markets, or to migrate to seek work in urban areas. The areas in which ethnic minority people live are also least well-served by state services, both in quantitative and qualitative terms, and ethnic minority people are generally less likely to be in positions of authority in local administrations, beyond the village level.

Spatial Factors Driving Poverty and Inequality

In seeking to explain this situation, clearly spatial factors are important. Ethnic minorities generally live in the most remote, usually upland regions. These areas are usually not agriculturally fertile or easy to farm, making accumulation through agricultural production difficult. Even in commodity areas where upland farming has some comparative advantage, in coffee production for example, or specialised commodities like cardamom or tree resins, the relative remoteness of upland areas and poor transport infrastructure and services make marketing in higher value markets by ethnic minorities themselves difficult, with middlemen traders from urban areas generally dominating the lucrative end of trade in these goods. There is also a high per capita cost in providing state services to remote areas, as settlement patterns are often dispersed. Consequently ethnic minorities often have to travel long distances to access state services, such as district health centres or secondary schools,as there isn’t the density of population to warrant locating schools and health centres in every village. The quality of services is also often poorer in remote areas, with health and education officials, for example, reluctant to work in remote areas and high levels of absenteeism of state officials resulting. Distance and remoteness, therefore, play a key role in creating and sustaining disadvantage for ethnic minorities. However, if ethnic minority poverty were solely caused by remoteness, then poverty would be shared across both ethnic minority and majority ethnic groups living in remote areas. This clearly isn’t the case. Instead, studies consistently show that majority ethnic groups living in the same areas as ethnic minorities enjoy, on average, much higher standards of living and better human development outcomes. Clearly then, there is more to ethnic minority poverty than just remoteness.

The Ability to Communicate in the National Language

In all of the countries of the region, a key factor perpetuating poverty for ethnic minorities appears to be a lack of language skills in the majority ethnic language. Studies show that ethnic minority households that speak only an ethnic minority language, or have only limited capacity in the national language, are consistently amongst the poorest. Inability to speak the national language is also higher amongst ethnic minority women than men, reflecting girls disadvantage in accessing opportunities for education in comparison to ethnic minority boys. In fact language competency seems to be key to accessing improved livelihood prospects across a range of domains: markets in remote rural areas, for example, are often dominated by traders from majority ethnic groups, so interacting in commercial markets requires the ability to speak the national language. Similarly, in either gaining employment outside of agriculture, or in gaining a position as a state official, language competency is critical. Smaller ethnic minority groups in the region are notably less likely to speak the majority language, whilst larger groups, such as the Tay or Khmer in Viet Nam, seem able to make use of their own networks to a degree to overcome language disadvantages in commodity and labour markets. Ability to speak the majority language iskeythough,in being able to participate in mainstream economic life both in rural areas, and in wider regional and national economic networks.

Completing Schooling and Educational Achievement

Smaller ethnic groups are generally the poorest and most disadvantaged across the region, and have the lowest educational attainment. Years of completed education is also therefore a key signifier of poverty or development, with households less likely to be living in poverty according to the years of completed education of the household head. Given that ethnic minorities have, on average, less years of completed schooling than majority households, education can also be considered a key driver of ethnic minority poverty in the region, with studies showing that household income is increasingly closely related to the years of education of a household head. Better educated households are also likely to have fewer children, with the high care burden of ethnic minority households cited in studies across the region as a factor in perpetuating ethnic minority poverty.

Mobility and Migration

A lack of formal education and language ability resonates in many ways, particularly in determining household mobility. Migration is increasingly viewed as a key component in improving social and economic wellbeing for rural people: households that are highly mobile can engage in economic networks and opportunities in urban areas where the returns are higher, and in more profitable activities, such as trading or seasonal off-farm employment in construction or other industries. The combination of education and mobility is an almost guaranteed pathway out for poverty for rural households. Throughout the region however, studies show that ethnic minorities are consistently less mobile than majority ethnic groups in participating in wider commercial networks and opportunities. A lack of mobility of ethnic minorities extends to accessing health services too, with ethnic minorities more likely to be reliant on village and localised health centres, and less likely to be able to travel to district or other centres to access better medical care, or other services.

Accessing Higher Levels of the Education System

A lack of mobility may also mean that ethnic minorities are less likely to progress on to further education, though the reasons for fewer minorities making the transition in education are complex. Certainly the poverty of ethnic minority households appears to make them less able to invest for the long term in children’s education, even though they may view this as an imperative in breaking the inter-generational cycle of poverty. Participatory studies from the region show that ethnic minority households often understand very well the importance of education to improving household prospects in the long term, but also face the need to put children and youth to work on subsistence tasks in the short term. Ethnic minority areas often only have rudimentary schooling, combining many ages in one class, and although states in the region recognise the importance of boarding ethnic minority children in larger towns in order to access better education, there are also often social constraints for ethnic minorities. Experience of discrimination for ethnic minorities away from their own areas is one powerful deterrent, as well as a lack of income for households to be able to subsidise children’s board and lodging in larger towns, when government subsidies are inadequate to cover the full cost. Ethnic minorities’ lack of mobility is therefore complex, and not easily reducible to a ‘cultural’ proclivity of ethnic minorities not to want to travel far from home, as is sometimes argued.

Lack of Integration into Cash Crop Production and Markets

Ethnic minorities are overwhelmingly engaged in agriculture throughout the region, and in China. But what often distinguishes ethnic minorities from ethnic majority neighbours in upland areas is the degree to which each is engaged in commercial, cash crop production. Generally speaking, survey data reveals that ethnic minorities are more likely to be engaged primarily in production exclusively for household consumption, and of crops with a low market value. Even for high value crops which ethnic minorities do produce, such as rice, they appear to sell less in commercial markets, and keep more for home consumption, than ethnic majority households that are more integrated into cash economies. Conversely, ethnic majority households have larger incomes which are composed more from the returns of high value cash crops, such as coffee, rubber and cashew. Of course the experience across the region differs significantly but a key feature of ethnic minority livelihoods that holds constant is a lack of integration into commercial agricultural commodity markets. This can be a reflection of the generally poorer quality of land that ethnic minorities have in comparison to ethnic majority groups, but is also a reflection of ethnic minorities lack of participation in, or even exclusion from, commercial networks for the development and sale of cash crops, which are more easily accessed by upland ethnic majority farmers with language, ethnicity and kinship linkages to urban trading networks and middlemen dealers. Ethnic minorities in the region often have significant forestry holdings in their land portfolio’s but over past decades, in response to concerns for environmental protection and the preservation of upland watersheds for downstream water users, forestry exploitation has increasingly been closed as a livelihood option, with ethnic minorities instead often paid by the state to be custodians or guardians of upland forests. The returns from forest guardianship do not compensate for the loss of income from forest exploitation, such as sales of timber, hunting wild game and production and sale of lucrative non-timber forest products.

In-Migration and the Changing Social and Economic Landscape of Upland Areas

A complicating factor in understanding ethnic minority disadvantage is the large-scale in-migrationof peoples into what were previously considered to be ethnic minority areas. This has been a trend in the uplands throughout mainland Southeast Asia over past decades, and has also occurred significantly in Indonesia and the Philippines. This in-migration is often of both lowland members of the majority ethnic group, and sometimes (as in the case of Indonesia, Viet Nam and Laos PDR particularly) of other ethnic minority groups from other parts of the country. In-migration has been both spontaneous and state directed, and has resulted in the fundamental spatial, social and economic redefinition of upland areas. In some places, areas that had previously been sparsely populated by long standing ethnic minority groups, have seen a massive influx of settlers that have rendered previously resident ethnic groups a small minority in areas they feel are their own lands. This is notable in the central highlands region of Viet Nam, for example, where previously long settled ethnic groups now consistently come out at the bottom in poverty and welfare assessments, having lost lands they previously farmed or managed in common, having little capacity in the majority ethnic language, and being generally ill-equipped to compete in the modern economy. The creation of competition and markets for land and other natural resources, and the increased pressure on landscapes and the environment in particular appear to be a factor in impoverishing some ethnic minority groups in the region. New opportunities which this opening of frontiers provide, such as the development of a tourism industry and related services, largely bypass local ethnic minority groups in favour of more commercially experienced in-migrants with better connections to urban economies and the tourism industry, with ethnic minorities often relegated to minor roles as exotic tourist curiosities at ethnic minority cultural shows and as street peddlers of handicrafts.

Civil Conflict as a Determinant of Poverty

Another important factor in accounting for ethnic minority poverty in some parts of the region, notably Myanmar and the southern Philippines, is ethnic minorities’ experience of civil conflict. Of the areas in Southeast Asia where major civil conflicts have occurred in past decades, all of them have been areas with high concentrations of ethnic minorities. In the southern Philippines the conflict in Mindanao is long standing and whilst the causes are complex, a significant factor has been large-scale in-migration of Christian Filipinos to what was predominantly Muslim Mindanao, and the perception of many local ethnic minorities of being repressed and discriminated against. In Myanmar, much of the upland regions of the country are inhabited by a patchwork of different ethnic minority groups and many have been in armed opposition to the central state for decades. Under these conditions of conflict it is extremely difficult for ethnic minority communities and households to establish stable settlements, access educational and health services, or begin to farm and accumulate in even a rudimentary sense. A durable and comprehensive peace settlement in these areas is therefore an essential prerequisite for ethnic minority social and economic development.

Ethnic Minorities Own Culture as an Obstacle to Change?

Ethnic minorities’ own cultures are often cited by officials as an obstacle to promoting development. Ethnic minorities, the argument goes, are incapable of adopting ‘modern’ attitudes and methods of production because they have either not reached the requite higher level of civilisation needed, or their traditional cultures tie them to a set of pre-modern customs, beliefs and practices that are not suited to modern forms of production and accumulation. Consequently ethnic minorities are frequently criticised for being unsuited to working in industrial production settings because they are unable to observe fixed working hours, or for being unable to take a long term view on private capital accumulation, whereby savings produce the capital base necessary to be successful in business. Instead, ethnic minorities are said to simply prefer to spend whatever they have, or distribute wealth amongst their kin with ‘no thought for tomorrow’. This is something of a simplification of the arguments frequently made, but this kind of stereotyping of a‘pre-modern’ state of ethnic minorities is remarkably prevalent in official discourses throughout the region. We believe this characterisation of ethnic minority culture as an obstacle to development is wrong on two major counts. First of all, it misrepresents ethnic minority cultures as unchanging and disconnected from the modern world. In fact the opposite is the case. Secondly, it imposes a fixed view of what constitutes development which can, in fact, be strongly contested.

Taking the first issue, of ethnic minorities being somehow disconnected from modernity and existing in a pre-modern state. In fact, the history of ethnic minorities throughout the region can be written as a constant struggle of ethnic groups to define and place themselves in relation to the development of dominant cultures and societies in the region, and in particular to the development of nation states. (Scott 2009). Far from being static and unchanging, ethnic minority culture and society in the region is constantly in flux, responding to environmental and social change in the same way as the predominantly urban, majority ethnic cultures of the region with which we are perhaps more familiar. Ethnic minority groups in the region have not been, therefore, disconnected from the modern world until now, but rather deeply embedded in it, enmeshed in social and economic relationships with other ethnic groups and similarly shaped by the processes of development in the region, and by the development of modern nation states.