2012-China-ASEAN Forum Report4

Table 8 elasticity of port on poverty

|

|

import |

export |

Overall effect |

|

Elasticity of port on trade |

1.02 |

1.07 |

- |

|

Elasticity of trade on poverty reduction |

Agricultural product import |

Agricultural product export |

|

|

National |

-0.05 |

1.03 |

0.9800 |

|

Eastern area |

-0.0559 |

0.3779 |

0.3220 |

|

Middle area |

-0.1454 |

2.116 |

1.9706 |

|

Western area |

-0.0228 |

0.5921 |

0.5693 |

|

Elasticity of port on poverty reduction |

|

|

|

|

National |

-0.0510 |

1.1021 |

1.0511 |

|

Eastern area |

-0.0570 |

0.4044 |

0.3473 |

|

Middle area |

-0.1483 |

2.2641 |

2.1158 |

|

Western area |

-0.0233 |

0.6335 |

0.6103 |

Due to lack of data, the elasticity of port on poverty reduction in table is simply multiplied by “Elasticity of port on trade” and “Elasticity of trade on poverty reduction”.

6 Conclusions and recommendations

In summary, through China and ASEAN have made great progress in trade facilitation, including port infrastructure construction, customs procedure reform, e-commerce development, as well as laws and regulations environment, the level of trade facilitation is still low compared with other developed countries, and it is uneven in ASEAN countries. So, China should learn from the experience of countries with a high degree of trade facilitation, enhance international cooperation to prompt trade facilitation and the development of national economy.

6.1 Impacts of trade facilitation on poverty reduction

It is easy to understand the mechanism of impacts of trade facilitation on poverty reduction, but the real case is much complicated than the theory, so it is much difficult to measure trade facilitation completely. This is mainly due to the dynamics and complexity of trade facilitation, the complexity of reasons of poverty and the complexity of impact channels between them.

Therefore this research takes port construction as a case study, to examine the impacts of port construction on poverty reduction. The results show that 1 percent increase in port efficiency causes 1.051 percent decrease of poverty index. For the middle area, the elasticity reaches 2.116 percent. It is smaller for eastern or western area. This is mainly because that in the eastern area the poverty problem is basically solved, the marginal contribution of trade facilitation is small, but in the mountainous western region, transportation is not developed and its connection with international market is not as close as eastern or middle areas, the contribution of trade in economic growth is not so high.

6.2 Enhancing capacity building in trade facilitation

6.2.1 To promote the reform of the customs further

In the global supply chain, customs clearance is the most important part. The burdensome and inefficient customs clearance measures, poor infrastructure cause high cost, and it’s easy to cause corruption. Therefore, the reform of customs procedures and internationalization of the customs rules will be conducive to the development of trade facilitation. Some developing countries think that the costs of customs reform and modernization are too high and there are technical difficulties, however, Chile and Singapore’s experiences show that the cost can be controlled, and investment on trade facilitation is likely to get a quick return.

6.2.2 To strengthen infrastructure construction for trade and investment facilitation

Construction of hardware infrastructure is an important component of trade and investment facilitation. In the China - ASEAN countries, only Singapore and Malaysia's port infrastructures reach the world advanced level, but the port facilities in China and other countries are not so high or below the world average level. Therefore China and ASEAN countries must focus on investment in infrastructure, especially ports, airports and other infrastructures, establish transportation system which is compatible with economic development. Meanwhile, we must strengthen exchanges and cooperation between customs and develop customs system which can meet international standards.

6.2.3 To improve development of e-business

The development of e-commerce in ASEAN countries is uneven. These countries should endeavor to enhance their informationization level, and attach great importance to the development of electronic commerce to promote its application in trade facilitation. Firstly, the vigorous development of the network and further investment in the network infrastructure should be given higher priority. At the same time, the e-commerce related laws and regulations should be improved.

6.2.4 To improve the institutional environment

Firstly, the policy transparency should be improved further and policy should be kept stable and continuous. On the one hand, the administrative department of trade and investment should increase the transparency of trade and investment policies. The laws and regulations about trade and investment should be published in official publications or on the government website; it can not be executed before publishing. On the other hand, the approval procedures should be simplified, standardized. The law enforcement should also be enhanced. Finally, the coordination mechanism of trade and investment facilitation should be established. The related administrative departments should continue to expand the dialogue and communication with foreign companies, build a set of the new management model so as to achieve "win-win".

6.3 To enhance coordination between China and ASEAN in trade and investment facilitation

6.3.1 To promote unified standards

To adopt international standard is the most simple and effective way of the trade facilitation within China-ASEAN countries. With the fast development of economic integration in China - ASEAN Free Trade Area, the unified standards play increasingly important role in the promotion of international trade and the establishment of a technical trade measures. China and ASEAN countries should try to make their own domestic standards based on international standards, and try to adopt international standards in priority areas. Try to unify the regulations and procedures. Trade agreements, domestic laws and regulations related to international standards should be consistent within China-ASEAN area.

6.3.2 To establish trade facilitation committee in all countries of China-ASEAN area

Trade facilitation involves wide areas and multi-sectors. Each country should establish the institute to coordinate the different sectors. On the other hand, fast and effective coordination mechanism among different countries should also be enhanced. First of all, each country should achieve information sharing within its country, establish the central database of trade facilitation and ensure data updated so as to provide complete and accurate information. Secondly, each country should form the effective decision-making and information communication mechanism at the government level. Finally, each country should establish a consultative mechanism with foreign trade enterprises, know about the issue and impact of trade facilitation, and solve the problems in trade facilitation timely.

Generally each of China-ASEAN should pay more attention to the initiative of the establishment of the National Trade Facilitation Committee in Doha Round negotiations, cooperate to promote the development of trade facilitation, improve the China-ASEAN cooperation level, strengthen trade and investment cooperation partnership and promote the extensive development of trade facilitation jointly.

References

Asian Development Bank, 2009, Toward a strategy for transport and trade facilitation (TTF) in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), Draft for discussion purposes only, September 15.

Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation, 2002, Trade Facilitation: A Development Perspective in the Asia Pacific Region.

APEC. Assessing APEC The liberalization and Faciltation: 1999 Update[R].EC Committee, Singapore, 1999.

APEC. Trade Facilitation and Trade Liberalisation: From Shanghai to Bogor. EC Committee, Singapore, 2004.

Centre for International Economics, 2005, Open economies delivering to people. Regional integration and outcomes in the APEC region, prepared for APEC’s Mid-term stocktake of the Bogor Goals.

DFAT (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade) 2002, APEC Economies, Realizing the benefits of trade facilitation. Report prepared by the CIE for the APEC Ministerial Meeting, Los Cabos, Mexico.

Kim S, H Lee, IPark.Measuring the Impact of APEC Trade Facilitation:A Gravity AnMysis. Paper presented at theAPECEC Committee meeting in Santiago, Chile, 2004.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1999, Open markets matter: the benefits of trade and investment liberalisation, OECD Policy Brief, October, pp. 1–12.

OECD, 2005, Costs and benefits of trade facilitation, Policy Brief, October.

Shepherd, B. and Wilson, J. 2008, Trade facilitation in ASEAN member countries: Measuring progress and assessing priorities, World Bank, policy research working paper 4615.

Stone, S. and Strutt, A. 2009, Transport infrastructure and trade facilitation in the Greater Mekong Subregion, Asian Development Bank Institute.

United Nations, 2003. Income distribution impact of trade facilitation in developing countries. Economic and Social Council, background material for the Second International Forum on Trade Facilitation, Geneva.

Wilson J S, C L Mann, T Otsuki.Assessing the Potential Benefit of Trade Facilitation:A Global Perspective //World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3324, 2004.

Wilson J S, C L Mann, T Otsuki.Trade Facilitation and Economic Development:Measuring the Impact //World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2988, 2003.

Yann D. Cost and Benefits of Implementing Trade Facilitation Measures under Negotiations at the WTO: an Exploratory Survey //Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade Working Paper Series, No. 3, 2006.

单君兰,周苹. 基于APEC的贸易便利化测评及对我国出口影响的实证分析[J]. 国际商务研究,2012,(1).

匡增杰. WTO贸易便利化议题谈判进程回顾与前景展望[J]. 世界贸易组织动态与研究,2007,(5).

李涛,褚增龙. 贸易便利化对我国海关监管的挑战及其对策[J]. 贵州商业高等专科学校学报,2006,(1).

厉力. 贸易便利化视角下的中国原产地规则改革建议[J]. 国际贸易,2011,(5).

梁德顺. 贸易便利化与中国[J]. 金融经济,2006,(16).

刘芳. 贸易便利化下的海关行政裁定制度研究[D]. : 复旦大学,2011.

刘雅楠,张马俊. 贸易便利化:发展中国家的机遇与挑战[J]. 国际经济合作,2004,(7).

倪冬生. 通向贸易便利化之路[D]. : 复旦大学,2011.

欧阳晔鑫. 中国—东盟自贸区建设中的贸易便利化[J]. 思想战线,2010,(S2).

沈铭辉. 东亚国家贸易便利化水平测算及思考[J]. 国际经济合作,2009,(7).

宋棋. 浅谈中国—东盟自由贸易区建设中的贸易便利化问题[J]. 思想战线,2011,(S1).

孙林,徐旭霏. 东盟贸易便利化对中国制造业产品出口影响的实证分析[J]. 国际贸易问题,2011,(8).

孙衷颖. 区域经济组织的贸易便利化研究[D]. : 南开大学,2009.

王文浩,日本贸易便利化现状分析,合作经济与科技,2009.14。

王勇. WTO的贸易便利观与中国的贸易便利化探析[J]. 现代经济探讨,2007,(2).

闻学祥. 贸易便利化背景下加强海关有效监管的几点思考[J]. 上海海关学院学报,2010,(1).

翁国民,陆娟芳. 论优化合格评定程序与贸易便利化[J]. 上海财经大学学报,2006,(5).

邬展霞,沈玉良,刘奕彤. 沪港服务业税收环境的对比评析——基于贸易便利化的视角[J]. 上海经济研究,2011,(3).

吴敏. 美国对外贸易区的贸易便利化制度及对我国保税港区的启示[J]. 法制与社会,2010,(8).

谢娟娟,岳静. 贸易便利化对中国-东盟贸易影响的实证分析[J]. 世界经济研究,2011,(8).

燕秋梅. 国际贸易便利化发展状况及我国的应对措施[J]. 商业时代,2010,(33).

杨莉. WTO贸易便利化改革经济影响的研究综述[J]. 首都经济贸易大学学报,2007,(3).

姚翠玲. 海关推动贸易便利化的措施与效果[J]. 天津职业院校联合学报,2010,(5).

曾铮,周茜. 贸易便利化测评体系及对我国出口的影响[J]. 国际经贸探索,2008,(10).

张海冬. 浅谈运用海关风险管理推动我国贸易便利化[J]. 市场周刊(理论研究),2011,(11).

张立莉. 云南省与东盟国家经贸合作贸易便利化行动成本效益评析[J]. 东南亚纵横,2010,(2).

张鲁彬. 贸易便利化与海关现代化互动关系研究[J]. 国际经济合作,2007,(12).

张然. 贸易便利化与中蒙海关联合监管研究[D]. : 复旦大学,2011.

张瑞莉. CEPA框架下的贸易便利化问题[J]. 黑龙江对外经贸,2004,(12).

周阳. 美国经验视角下我国海关贸易便利化制度的完善[J]. 国际商务研究,2010,(6).

邹彦华. 疏通企业贸易便利化通道[J]. 中国外汇,2010,(1).

The Impact on Ongoing Trade Facilitation Improvement on Export-oriented Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Indonesia

Tulus T.H.Tambunan

Center for Industry, SME and Business Competition Studies, Trisakti University

1. Introduction

This study is about export-oriented micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Indonesia, which aims to examine their access to trade facilitation (TF). It uses the definition of MSMEs by the National Statistics Agency (BPS), which defines micro enterprises (MIEs) as units of production/firms with 0 to 4 workers; small enterprises (SEs): 5 to 20 workers; medium enterprises (MEs): 21 to 99 workers, and enterprises employing100 and more workers are categorized as large enterprises (LEs). The study has three main research questions: (1) do export-oriented MSMEs have access to TFs, such as trade finance, trade insurance, information on market and trade regulation/policies through internet, infrastructure such as well-constructed roads linking their clusters/production locations to main trading ports, transport facilities, testing laboratories, ware/storehouses, electricity and communication? (2) how helpful are those TFs in supporting their export?

Good TF measures and full access to TF are considered very important for MSMEs since the fact that MSMEs are very important in Indonesia not only because they generate employment, produce basic goods for middle and low income households and contribute significantly to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), but many of them do have great potential as exporters and Indonesia needs export to earn foreign currencies to replace the country’s dependency on foreign loans. Moreover, national data on MSMEs indicate that the majority (about 99 per cent) of them (about 51 million units in total) are from the category of MIEs and SEs, and people (owners and workers) engaged in these enterprises are from low income group. Due to their lacks of such as capital, technology, access to wider market, and human skilled, their productivity and income per capita are low. Even MIEs are generally considered as a pocket of poverty. But many MIEs are involved directly or indirectly in export activities.

Thus, with this fact it is obvious that the improvement in the performance (e.g. productivity and export growth) of MSMEs, especially MIEs and SEs, will contribute a lot to poverty alleviation, and making MSMEs more capable to do export would help much to meet that goal.

The study is based on: (1) desk research: academic literature on MSMEs, especially with respect to their export performance and their access to TF in Indonesia and in other Asian developing countries as a comparison (including studies done in e.g. India and Sri Lanka for ARTNeT); government and reports from various non-government organizations (NGOs) and other publications on TF and MSMEs access to TF in Indonesia; (2) secondary data analysis on MSMEs in Indonesia focusing on export-oriented MSMEs; (3) key informant/indepth-interview (e.g. related local government officials, NGOs assisting MSMEs in doing export); and (4) field surveys in two clusters of export-oriented MSMEs with total respondents:30 producers in Solo and 52 producers D.I. Yogyakarta; both regions are located in Central Java. They were selected randomly and face-to-face interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire consists of a list of questions covering broad areas related to TF (see the appendix). The sample also includes some LEs to have a comparison picture regarding the research questions stated above.

2. Development of Indonesian MSMEs

Historically, Indonesian micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) have always been the main players in domestic economic activities, accounting for more than 99 percent of all existing firms across sectors (Table 1) and providing employment for over 90 percent of the country’s total workforce (Table 2), mostly women and the youth. The majority of MSMEs are micro and small enterprises (MSEs), which are dominated by self-employment enterprises without wage-paid workers. Many MSEs, especially micro enterprises (MIEs), are established by poor households or individuals who could not find better job opportunities elsewhere, either as their primary or secondary (supplementary) source of income. Therefore, the presence of many MSEs in rural as well as urban areas in Indonesia is considered as a result of current unemployment or poverty problem; not seen as a reflection of entrepreneurship spirit (Tambunan, 2006; 2008b; 2009a,b).

Table 1: Total enterprises by size category in all economic sectors in Indonesia, 2000-2009 (in thousand units)*

|

Size category |

2000 |

2001 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

|

MSEs |

39,705 |

39,883.1 |

43,372.9 |

44,684.4 |

47,006.9 |

48,822.9 |

47,720.3 |

52,327.9 |

52,723.5 |

|

Mes |

78.8 |

80.97 |

87.4 |

93.04 |

95.9 |

106.7 |

120.3 |

39.7 |

41.1 |

|

Les |

5.7 |

5.9 |

6.5 |

6.7 |

6.8 |

7.2 |

4.5 |

4.4 |

4.7 |

|

Total |

39,789.7 |

39,969.9 |

43,466.8 |

44,784.1 |

47,109.6 |

48,936.8 |

49,845.0 |

52,262.0 |

52.769.3 |

Note: * MSEs consist of microenterprises (MIEs) and small enterprises (SEs); MEs=medium enterprises; LEs = large enterprises.

Source: State Ministry for Cooperative and SMEs (www.depkop.go.id) and Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) (www.bps.go.id)

Table 2: Total Employment by Size Category and Sector in Indonesia, 2008 (workers)*

|

|

MIEs |

SEs |

MEs |

LEs |

Total |

|

Agriculture Mining Manufacture Elect, gas & water supply Construction Trade, hotel & restaurant Transport & communication.. Finance, rent & service Services

Total |

41,749,303 591,120 7,853,435 51,583 576,783 22,168,835 3,496,493 2,063,747 5,096,412

83,647,711 |

66,780 28,762 1,145,066 19,917 137,555 1,672,351 145,336 313,921 462,683

3,992,371 |

643,981 21,581 1,464,915 31,036 51,757 472,876 111,854 279,877 178,311

3,256,188 |

229,571 78,847 1,898,674 54,233 31,016 179,895 98,191 156,064 49,723

2,776,214 |

42,689,635 720,310 12,362,090 156,769 797,111 24,493,957 3,851,874 2,813,609 5,787,129

93,672,484 |

Note: * data at sectoral level are not yet available for 2009.

Source: State Ministry for Cooperative and SMEs (www.depkop.go.id) and BPS (www.bps.go.id)

Table 3: Structure of Enterprises by Size Category and Sector in Indonesia, 2008 (units)*

|

|

MIEs |

SEs |

MEs |

LEs |

Total |

|

Agriculture

Mining

Manufacture

Elect, gas & water supply

Construction

Trade, hotel & restaurant

Transport & communication..

Finance, rent & service

.Services

Total (percentage) |

26,398,113 (52.07) 258,974 (0.5) 3,176,471 (6.27) 10,756 (0.02) 159,883 (0.32) 14,387,690 (28.38) 3,186,181 (6.29) 970,163 (1.91) 2,149,428 (4.24)

50,697,659 (100.00) |

1,079 (0.21) 2,107 (0.41) 53,458 (10.28) 551 (0.11) 12,622 (2.43) 382,084 (73.45) 17,420 (3.35) 23,375 (4.49) 27,525 (5.29)

520,221 (100.00) |

1,677 (4.23) 260 (0.66) 8,182 (20.63) 315 (0.79) 1,854 (4.68) 20,176 (50.88) 1,424 (3.59) 3,973 (10.02) 1,796 (4.53)

39,657 (100.00) |

242 (5.54) 80 (1.83) 1,309 (29.94) 125 (2.86) 245 (5.60) 1,256 (28.73) 319 (7.30) 599 (13.70) 197 (4.51)

4,372 (100.00) |

26,401,111 (51.50) 261,421 (0.51) 3,239,420 (6.32) 11,747 (0.02) 174,604 (0.34) 14,791,206 (28.85) 3,205,344 (6.25) 998,110 (1.95) 2,178,946 (4.25)

51,261,909 |

Note: * data at sectoral level are not yet available for 2009.

Source: State Ministry for Cooperative and SMEs (www.depkop.go.id) and BPS (www.bps.go.id)

The majority of MSMEs in Indonesia are involved in agricultural activities (Table 3). In 2008 there were about 42.7 millions laborers in that sector, of which almost 99.5 percent worked in MSMEs. While, in terms of unit there were about 26.4 millions units in that sector, of which almost 100 percent were MSMEs. Within the MSMEs, MIEs are mostly agricultural-oriented. About 52 percent of total MIEs were found in the sector, compared to only 0.2 percent and 4.2 percent with respect to, respectively, SEs and MEs. In the manufacturing sector, MSMEs are traditionally not so strong as compared to LEs. This structure of MSMEs by sector is, however, not an Indonesian unique. It is a key feature of this category of enterprises in developing countries, especially in countries where the level of industrialization is relatively low.

3. Export Performance

Other important feature of MSMEs in Indonesia (as in developing economies in general) is that most of the enterprises are domestic market oriented for a number of reasons. The most important one is their lack of four key inputs, namely (i) technology and skilled workers (so they cannot make highly competitive products that meet world standards), (ii) information especially on market potentials (including current changes in market demand/taste), (iii) global business strategies, and (iv) capital for financing export activities. Especially for MIEs and SEs, doing international marketing is too costly, as they have to deal with such as promotion, distribution, communications, export license, transportation and logistic.

Nevertheless, based on government data, in some groups of industries, many Indonesian MSMEs do export. Government data show that MSMEs’ total exports (non-oil and gas) continue to grow from year to year (Table 4); although in 2009, their total exports declind slightly (Figure 1). Probably the decline was caused, among other factors, by the 2008/09 global economic crisis. During that crisis, many Indonesian exports of manufactured goods including furniture which is produced and exported mainly by MSMEs, declined.

Table 4: Export Values of Indonesian MSMEs, 2006-2009 (Rp billion/US$ million)

|

Year |

Non-oil and gas Export |

||||

|

MIEs |

SEs |

MEs |

LEs |

Total |

|

|

2006

2007

2008

2009 |

Rp13,477.2 US$1,347.7 Rp15,024.9 US$1,502.5 Rp 20,247.2 US$2,024.7 Rp 14,375.3 US$1,597.26 |

Rp29,365.4 US$2,936.5 Rp34,661.8 US$3,466.2 Rp44,148.3 US$4,414.8 Rp36,839.7 US$4,093.3 |

Rp79,108.2 US$7,910.8 Rp93,325.7 US$9,332.6 Rp119,363.6 US$11,936.4 Rp 111,039.6 US$12,337.7 |

Rp656,231.8 US$65,623.2 Rp749,999.9 US$75,00.0 Rp915,091.2 US$91,509.1 Rp790,835.3 US$87,870.6 |

Rp778,182.6 US$77,818.3 Rp893,012.3 US$89,201.2 Rp1,098,850.2 US$109,885.0 Rp953,089.9 US$105,898.9 |

Source: State Ministry for Cooperative and SME (www.depkop.go.id)

Figure 1 Development of Indonesian MSMEs’ exports (non-oil and gas), 2000-2009 (Rp trillion)

Source: State Ministry for Cooperative and SME (www.depkop.go.id)

4. MSMEs’ Access to Trade Facilitates

As explained in Grainger (2009), TF is the simplification, harmonization, standardization and modernisation of trade procedures. It seeks to reduce trade transaction costs at the interface between business (i.e. exporters and importers) and government and is an agenda item within many customs related activities. These include WTO trade round negotiations, supply chain security initiatives, development and capacity building programs, as well as many customs modernisation programs. The United Nations Centre for Trade Facilitation and Electronic Business (UN/CEFACT) defines TF as the simplification, standardization and harmonization of procedures and associated information flows required to move goods from seller to buyer and to make payment (OECD 2003). In UN/CEFACT and UNCTAD (2002), it is stated that TF covers: trade procedures, customs and regulatory bodies, provisions for official control procedures applicable to import, export and transit including: general arrangements, customs controls, official documentation, health and safety, financial securities, and transshipment, provisions relating to transport and transport equipment, including: air transport; sea transport; and multimodal transport, provisions relating to the movement of persons, provisions relating to the management of dangerous goods, provisions relating to payment procedures, provisions relating to the use of information and communication technologies, provisions relating to the commercial practices and the use of international standards, and legal aspects of TF.

While TF frequently refers to all measures that can be taken to facilitate and ease cross-border trade flows, there is no standard formal definition of trade facilitation. In a broader sense of the term, as stated in Damuri (2006), TF can be defined as any action intended to reduce transaction costs which affect the international movement of goods, services, investments and people. For some others such as Moïsé, et al. (2011), TF refers to policies and measures aimed at easing trade costs by improving efficiency at each stage of the international trade chain. They also cited the WTO definition of TF, which is the simplification of trade procedures, which is understood as the activities, practices and formalities involved in collecting, presenting, communicating and processing data required for the movements of goods between countries/economies. Therefore, removing administrative and technical barriers to trade, as a way to reduce trade transactions costs, and facilitate more inclusive participation of MSMEs in international trade, must also be considered as part of improving TF measures.

For Indonesia, not so many studies on this matter have been conducted so far, and among the existing ones was by Damuri (2006), which can be seen among serious studies on TF in Indonesia, and for it he also did a survey of private sector actors from different lines of business activities, including exporters and importers. He concludes that although Indonesia has already implemented various TF measures currently discussed in the WTO TF negotiation, the degree of implementation of those measures still needs significant improvement in order to provide simplified and harmonized procedures related to trade. In response to increasing demand for better public services related to trading activities, the Indonesian government has launched a number of programs to improve trade procedures, including a customs related administration program. The programs are also in line with several international agreements on trade facilitation, in which Indonesia has actively participated. Those include the APEC Trade Facilitation Action Plan and ASEAN Customs Agreement. Findings from his survey reveal that the implementation of several TF measures needs significant improvement. While the availability of information related to trading activities has shown significant progress, this remains the most problematic issue. The survey also found that many traders faced difficulties in meeting certain regulations and procedures based on new regulations, as they were issued and implemented at the same time, without any notification whatsoever. The lack of formal consultative mechanisms exacerbated the situation even further. Rampant illegal conduct of officials has eroded the competitiveness of Indonesian products. Traders surveyed complain that improper conduct of trade-related officials do not only increase costs, but also slow down their activities, which might lead to the loss of business opportunities and substantial market share.

Another research is from Rahardhan, et al. (2008) which may also give some clue about the impact of TF on export activities in Indonesia. They examined the impact of ASEAN TF on trade volume of main important commodities from East Java. For the purpose, they conducted in-depth interviews with exporters from all sizes and some key officials. The findings from the interviews show that from the own opinion perspective of the respondents, the most important trade facilities are the followings. With respect to tariff barriers, the respondents see that removing all problems related to custom procedure, tariff differences in line with declining MFN tariff, administration procedures in filling all required forms, and information on the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT) scheme have the most important effects. With respect to non-tariff barriers, the elimination of problems related to import license, regulations on specific technical requirements, costs of various extra taxes, including tax of foreign exchange transactions, import license, and many others, and procedure of custom clearance.

Unfortunately, until now not so many studies have been conducted specifically on export-oriented MSMEs’ access to TFs and the impact of their access to TF on their export volume and cost in Indonesia. Although some official statements made by government agencies may suggest indirectly that access to TF is still a serious constraint for MSMEs. Trade finance is among important TF, and recently, Bank Indonesia (BI) states that still 50 percent of total MSMEs in Indonesia are still not served by banks (http://ditjenpdn.kemendag.go.id/index.php/public/information/articles-detail/berita/30), as also confirmed before by e.g. Tables 17 and 18. While many studies elsewhere shows that liquidity constraint is among important factors that hinder many firms, including MSMEs, to become sustainable exporters. Also, statement given by the Coordinating Ministry for Economy, Hatta Rajasa, during the KPPOD Award 2011 in Jakarta (July 2011) that MSMEs have difficulties in getting licenses, which may also include export license and license for importing raw materials. His statement was based on findings of a survey conducted by KKPOD in collaboration with the Asia Foundation (TAF).

Probably a study done before by Tambunan (2009) can be seen as the only serious efforts to examine the impact of TF on export activities of MSMEs in Indonesia so far. He did a survey of 39 export-oriented MSMEs in the wood furniture industry in Central Java conducted in August 2009. His main argument as the basis for conducting his study is the fact that many export-oriented MSMEs or those which have great potentials to become exporters could not do export by themselves/directly, but must through the third party such as large-sized exporting or trading companies. He states that there are at least two main reasons. First, financial problem: most MSME, especially MSEs, lack of capital to pay all costs involved with export activities is limited; while, on the other hand, not easy for them to get enough support from banks or other formal financing institutions. Second, institutional and business constraints that MSMEs could not solve because of (i) they do not have direct access to export market or no access to information on export market opportunities and requirements; (ii) they are not able to adjust to rapid changes in export market; (iii) there is high risk in payment and shipment; (iii) payment is delayed, which small exporters/producers could not endure as they need daily cash flow very badly; (iv) there is higher cost involved in direct export activities by MSMEs; and (v) and no access to TF. During the survey, the respondents were requested to mention which form of TF is considered as the main problem in doing export. The finding shows the following six forms of TF mentioned by the respondents, though different individuals (or groups of individuals) have different perceptions about the degree of the problem with respect to each of the items as shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Form of TF as the main problem faced by the respondents

|

Form of TF |

Respondents (N=39) |

|

|

Number |

% of the total |

|

|

Custom regulations and cost involved, Shipment, Documents required for export, Environment, health and safety regulations, Harbor facilities and cost involved Trade financing (letter of credit and/or trade credit)

Total |

7 2 4 3 2 21

39 |

|

Source: field survey

Based on this finding, however, one cannot conclude that such items of TF have a bias against MSMEs. The finding can only indicate that among those items, lack of access to trade financing reveals as the most problem for the majority of the respondents. This finding is interesting due to the fact that many banks in Indonesia have been doing many efforts to facilitate SMEs in trade. Not only private commercial banks such as Bank International Indonesia and Standard Chartered Bank, but also several state-owned banks such as Bank Mandiri, BRI, BNI and Bank Ekspor-Impor Indonesia provide trade facilities to SMEs. The trade facilities include loan for working capital, investment credit, letter of credit (L/C), foreign exchange line, bank guarantee, shipping guarantee, business management account –international trade (current account with interest and integrated trade facility), Loans Against Trust Receipt (LATR) , Inward Bills Collection (IBC), Invoice Financing for Suppliers (purchase) , Credit Bills Negotiation (CBN) Clean and Discrepant , Pre-Export Financing , Export Bills Collection (EBC), etc.

So, this new study that comes with much larger sample from two regions should be considered as an effort to add more information on the issue being studied. This new study may address the gaps by focusing more on MSMEs’ access to TF, their way of doing export (directly or indirectly), their main constraints in doing export, and their own perception about competition as a direct result of free trade agreements and the impact on their exports.

5. Surveys: Findings and Discussions

5.1 Profile of the Sample

As already explained briefly in the introduction, two field surveys on export-oriented MSMEs in two different locations/cities in Central Java have been conducted for this study, namely Solo and D.I. Yogyakarta. Total respondents surveyed are 82 producers with the following specification: Solo: 20 LEs and 10 MSMEs (total 30 respondents), and D.I.Y:3 LEs and 49 MSMEs (total 52 respondents). As said in the methodology section of this paper, the sample also includes some LEs as a comparison, and the initial plan was to have more MSMEs than LEs in Solo. However, during the observations and the survey, it was not so easy to find MSMEs which are still doing export. It was found some MSMEs which did not do export any more or had stopped doing that since many years ago for various reasons, including hard to compete and no capital to financing export activities.

The commodities of the sampled respondents are ranging from wood/bamboo and rattan furniture, cloths to handicrafts. Among the surveyed LEs, the largest respondent employs wage-paid more than 1000 workers, and some of them have more than one factory located in surrounding Solo city, and the smallest respondent has 100 wage-paid workers also in Solo. Among the surveyed MSMEs, the largest respondent has been found to employ 86 workers and there is one respondent without wage-paid workers (known in the literature as 'self-employment unit') and many with only two workers. The majority of the sampled MSMEs are from the MSEs category, and the sample also includes a large number of women entrepreneurs.

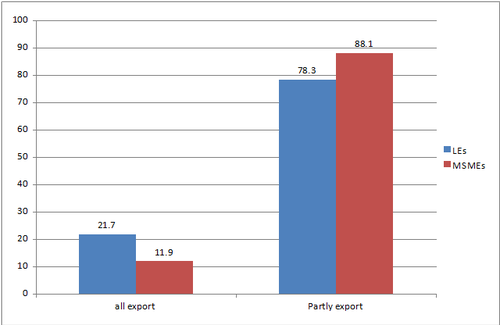

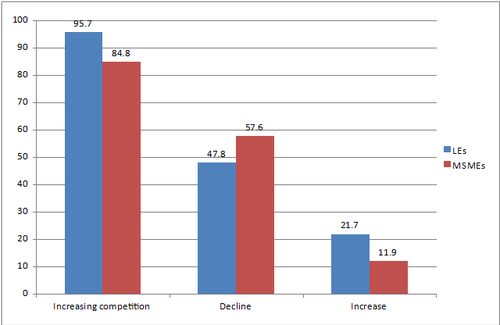

Figure 2: Market Orientation of the Sampled Respondents

Source: field surveys 2012

With respect to the degree of involvement in export activity, among the sampled firms LEs have been found to be more export-oriented than their smaller extent, in the sense that there are more LEs than MSMEs in the sample with production 100 percent for export. As shown in Figure 2, about 21.7 percent of the sampled LEs serve only foreign market, while it is only 11.9 percent with respect to MSMEs. This finding may be expected generally, as MSMEs in general (especially MSEs) have more difficulties than their larger counterparts in doing export due to their lack of skills, information and finance. These are crucial inputs that every firms/producers need not only to do export technically, but also to identify market opportunities or to understand current market changes, to have full knowledge on existing rules and regulations related to export activities as well as regulations related to import activities in countries of destination, and to do promotion and regional or global marketing activities.

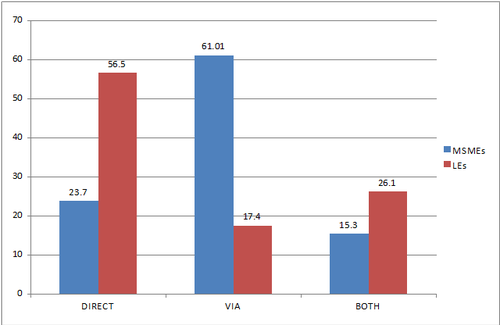

It also reveals from the field surveys that there are more LEs than MSMEs in the sample which do export directly without the help of intermediate agents such as traders or trading companies or collectors. As can be seen in Figure 3, about 56.5 percent of the surveyed LEs do export by themselves, compared to only around 23.7 percent of the sampled MSMEs. The reason is the same as mentioned above that MSMEs in general are not able by themselves to do export due to their shortages in knowledge on regional/international marketing, skill in bargaining and other aspects directly related to export activity, and capital to do the whole process of export, from identifying potential buyers abroad, promotion, export administration procedures to shipping.

Figure 3: Ways of Doing Export of the Sampled Respondents

Source: field surveys 2012

5.2 Findings and Discussions

5.2.1 Main Constraints in Doing Export

National data on MSEs from BPS shows that lack of raw materials (shortage in domestic supply caused mainly by unlimited export of raw material or stock is available but too expensive), marketing difficulties, and lack of capital are their three main constraints (BPS, 2010). During the survey, the respondents were given a list of problems related to crucial inputs/sources of growth, i.e. raw material, fund, trade financing, information, technology, skilled workers, transport facilities, energy, market (identifying/getting buyers), distribution networks, and others (if any), and they were asked to select only two of the listed items in which they face serious constraints.

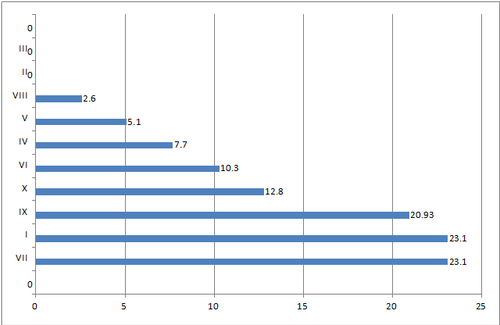

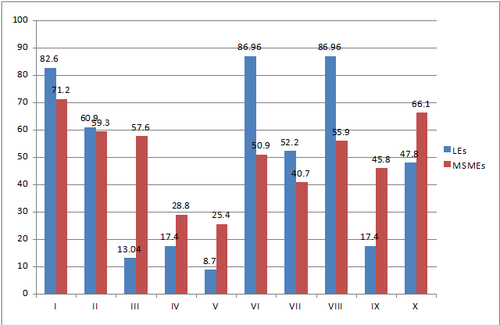

As can be seen in the following two figures, the structure of main constraints regarded by the respondents is different between MSMEs and LEs. With respect to LE category, the structure of respondent by kind of constraint shown in Figure 4 indicates that identifying/getting buyers abroad appears as the most problem for the largest percentage of the respondents. Lack of access to such as fund/credit, transport facilities, energy and skilled workers seem to be less serious problem for the majority of them. Even, none of them said that they have serious problem in getting access to trade finance. It is not surprise given the fact that in general MSMEs, not LEs, which have difficulties in getting credit, including trade finance, from banks or other non-bank financial institutions.

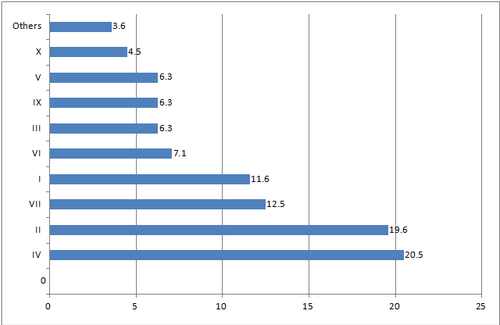

Figure 4: Percentage of Total Respondents from the LE category by Type of Main Constraint

Note: (I) access to raw materials/other inputs; (II) access to money to financing working capital; (III) access to trade financing; (IV) access to information on market, trade policy/regulation, and others; (V) access to technology; (VI) access to workers with high skills; (VII) identifying/getting potential buyers in abroad; (VIII) access to efficient transportation facilities; (IX) establishing distribution networks abroad: (X) sustained and cheap supply of energy; and others.

Source: field surveys (2012)

Figure 5: Percentage of Total Respondents from the MSMEs category by Type of Main Constraint

Note: see Figure 12 for types of constraint

Source: field surveys (2012)

For the category of MSMEs, as shown in Figure 5, lack of access to information on market condition or changes or potential and current trade policies and regulations/deregulations is the most serious constraint for the largest percentage of respondents. This is in line with the figure at the national level shown by national data (BPS) that difficulties in doing marketing, which caused among other factors by lack of comprehensive and update information on outside markets, are among serious problems for many MSEs, particularly for MIEs. Many reasons that can be thought of for their lack of access to information, which ranges from having no money enough to use/purchase information technology (IT) to having no knowledge on how to get the right information or to do good communications, and this is mainly because their low level of formal education. Especially in the category of MIEs, which is the dominant category within MSMEs in Indonesia, the owners/producers have only primary education, and even many of them never finish their school. So, it is hard to expect (if not impossible) someone with only have maximum 5 degree primary education can read very well and understand the meaning of information he/she has and to communicate especially in English.

One interesting finding during the field survey, yet related to the problem of information, was that the majority of the respondents said that they do not know what are the current government regulations that in fact affected their export activities or what are the current programs initiated or designed by government specially to support exporters.

5.2.2 Access to Trade Facilitations

No doubt that in this era of globalization and world trade liberalization in which competition is increasingly tight with more risks of failure caused by such as unanticipated global economic crises, global political instability, sudden market changes, and unexpected change in trade policies, access to trade facilitations (TFs) for individual exporters, ranging from trade finance, trade insurance, information, and testing laboratories has become more crucial than ever before. For instance, although it has enough capital, a firm financing its external trade activities through banks or backing up its export by trade insurance faces less risk financially than otherwise.

During the field surveys, the respondents were given this question with a list of types of TFs (see Appendix), and they were requested to answer yes or no for each type. If the answer is no, the respondents should give the main reason, whether because the procedure is too complex for them, or too expensive, or they just do not now that particular facility does exist (they never heard), or other reasons. The findings may suggest that LEs have more access to all TFs they need to support their export activities than their smaller counterparts.

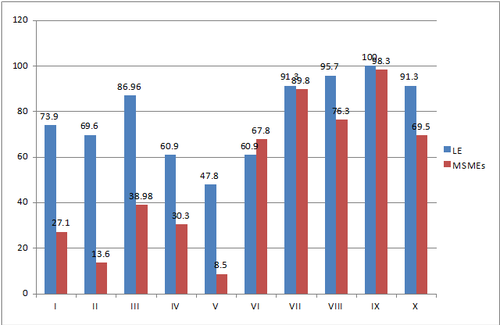

As can be seen in Figure 6, for export financing, around 73.9 percent of total 23 LEs in the sample have access, while only 7.1 percent of total 59 MSMEs surveyed. For trade insurance, almost 70 percent of the sampled LEs have access to, compared to only around 3.6 percent of the sampled MSMEs. For access to information, the comparison is almost 87 percent of LEs versus almost 39 percent of MSMEs. For the remaining items, it reveals the same structure that LEs are much better than MSMEs. If these findings may represent the real condition of MSMEs in general and the export-oriented ones in particular in Indonesia, it is then no surprise what national data has shown that export share of MSMEs in the manufacturing industry is much smaller than that of LEs.

Figure 6: Percentage of Respondents by Access to TFs

Note: (I) export financing; (II) trade insurance; (III) information; (IV) laboratory; (V) storage; (VI) training; (VII) telephone; (VIII) internet; (IX) electricity; (X) promotion.

Source: field surveys 2012

Next, with respect to the main reason of not having access to some of the listed TFs, based on how many times the same reasons mentioned by respondents, as shown in Figure 7, not knowing or personally uninformed (II) reveals as the main reason, both for LE and MSME respondents. However, in the percentage term, among those who have no access, there are more MSME than LEs respondents (i.e. 84% versus 16%) who said that they never heard or not knowing as the main reason. As a comparison, national (BPS) data 2010 on MSEs in the manufacturing industry support this finding which suggests that many MSMEs, especially MSEs, in Indonesia do not make a good use of existing facilities simply because they are not aware that such facilities exist or do not know the procedure. First, the data show that 2,172,753 out of total 2,732,724 MSEs surveyed did not borrow money from banks or other non-bank financial institutions, and around 17.5 percent of them said that not knowing procedure is their main reason. Second, the data also show that only 208,305 out of the surveyed MSEs received business assistantship. From the remaining 1,964,448 MSEs which did not receive it, 386,605 respondents said that they are aware that such assistantship exists but they do not know the procedure, and not knowing at all is the main reason for other 1,489,106 respondents. Thus, in total, for around 95.5 percent of those not receiving business assistantship, lack of information/knowledge is the main cause.

Figure 7: Main Reasons of Not Having Access to Some Listed TFs

Note: (I) procedure too complex; (II) not knowing; (III) too expensive; (IV) other reason.

Source: field surveys 2012

There are two possible reasons for that, namely lack of information from the government side about the existence of particularly facilities, or/and, lack of activeness from the producers side in looking for information about facilities provided by the government. In many cases, owners of especially MSEs do not even know what kind of supports or facilities they really need which are good for their business performance. On the other hand, supporting facilities for MSMEs introduced/provided by ministries also often lack of wide promotion/socialization, so only a small number of MSMEs not only those located in Jakarta and other big cities but also whose owners have good connections or have built strong networks with ministries know about such facilities and have more chance to get access to them.

Within the group of MSMEs, next important reason is difficulty in procedure (I) with 96.6 percent compared to only 3.4 percent among LE respondents. The difficulty in procedure considered as also an important reason for many MSMEs for not making a good use of existing facilities including credit schemes from banks is also supported by the national data 2010, showing that approximately 9.8 percent of the sampled MSMEs not having loans from banks or other non-bank financial institutions said that difficulty to follow or to understand procedure in applying credits is the main reason.

This finding is understandable, given the fact that the majority of owners of MSMEs, particularly MSEs, have only primary education that often make them difficult in understanding the procedure in applying for or the system in using a facility. In other words, for low educated producers, the procedure of a facility may be too complex, which in fact not really. Too expensive (III) has been found as the next main reason of not having access to some of the listed TFs. For some other respondents, no need yet is their main reason (IV).

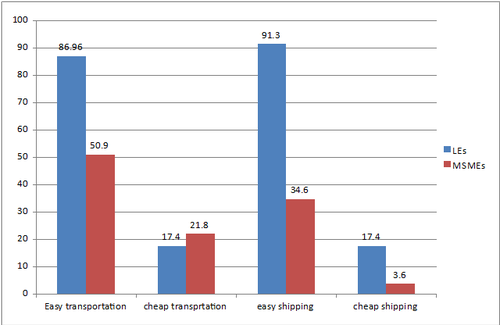

Other TFs which are also not unimportant, or even the most important ones, are services for getting export license, transportation (in quantity and quality) to harbor, airport or hub, and shipping. With respect to services for getting export license, three main questions for the respondents were: how much they have to pay, how much documents, and how many days they have to wait before they get it? The finding shows that total days LE respondents need to deal with export license vary from minimum only one day to the longest 30 days; while, interestingly, it is between 1 and 10 days for MSME respondents. For the cost, it also varies, ranging from minimum Rp 100.000 to more than Rp 10 million for both categories of respondents. For total documents, it ranges from only 1 to 8 documents for the LE respondents, while for the MSME ones, the range between 1 to 12 documents. For a broader picture of this issue, the World Bank report on Doing Business in 2009 does not give how many days an exporter to get its export license; it only gives total days for export, i.e. starting from the final contractual agreement between the exporter and the buyer abroad (importer) in Indonesia, namely 21 days, compared to East Asia and Pacific 23.3 days and OECD 10.7 days. For documents for export (in number): Indonesia 5, East Asia and Pacific 6.7 and OECD 4.5; and cost to export in US$ per container: Indonesia 704, East Asia and Pacific 902.3, and OECD 1,069.1.

Regarding transportation (not only such as road and railways but also means like container truck) and shipping, the key question for the respondents were: whether it is easy and cheap? As shown in Figure 8, the finding shows that more LE than MSME respondents who said that transportation is easy. But, for the costs, they have different opinions. More MSME than LE respondents said that transportation is cheap, while it is the opposite for the shipping cost. However, this is not really surprising finding. It can be that their export volume on average per individual firm is relatively smaller than that of individual LEs, so they do not need big trucks, and they often used/hired non-modern trucks to bring their goods to ports, or many MSME respondents export indirectly, so they are not directly involved in shipping.

Figure 8 Percentage of the Respondents by Easiness and Cost of Transportation and Shipping

Source: field surveys 2012

Finally, the respondents who have access to some or all of the listed TFs were asked whether the TFs are helpful for their export activities. The result shows that almost 96 percent of all respondents from the category of LEs who have access said it does; whereas it around 93 percent for the MSMEs category (Figure 9). Although the difference is not significant, this may suggest that LEs are more satisfied than MSMEs with existing TFs. There can be many reasons for that. It can be that trade insurance, for instance, is more suitable and cheaper for LEs exporting in large volumes than for MSMEs with smaller export volume. It can also because owners of especially MIEs who do have access to internet but do not know how to use it effectively, so they do not find the information they need.

Figure 9: Percentage of Satisfied Respondents Having Access to TFs

Source: field surveys 2012

5.2.3: Market Competition and Export Growth

The past quarter of a century has witnessed among many countries, across the development spectrum, an unprecedented level of activity in the process of trade liberalization. Today, the conduct of international trade in goods and services, either among countries in the same regions or between regions, is much easier than, say, two decades ago. There are more countries today that have undertaken significant trade reform and engage in the process of integrating their economies with the global economy. Indonesia (as with almost all other countries in the world), as a member of many regional/global organisation related to trade such as WTO, ASEAN and APEC, has commitment to fully adopt a free trade regime.

There is little doubt that international trade liberalization generates immense competitive challenges for all countries, especially open-economy oriented ones like Indonesia. Trade liberalization will affect, directly or indirectly, all firms from all sizes, and not only those serve external but also internal market oriented firms in all sectors. Theoretically, there are many ways through which trade liberalization affects individual local firms, and one among them is through increasing competition both in export markets and domestic market. In the domestic market, lower or elimination of existing import tariffs, quotas and other non-tariff barriers (NTBs) have the effect of increasing foreign competition as more and more imported goods and services enter the domestic market. This is expected to push inefficient, unproductive or uncompetitive local firms to improve their efficiency, productivity and competitiveness by eliminating unnecessary cost components, exploiting external economies of scale and scope, and adopting more innovative technologies and better management practices, or to shut down. Therefore, the openness of an economy to international trade is also seen in the increasing plant size (e.g. scale of efficiency), particularly as local firms adopt more efficient technologies, management, organization and methods of production.

Whereas in the export market, lower of existing import tariffs, quotas and other NTBs in the importing countries attract more suppliers from other countries. On the other hand, as trade liberalization also means elimination of all export limitations such as export tariffs and quotas, more countries become exporters, and thus domestic market in the importing countries will become more crowded, and for individual exporting countries this means more tight competition.

With respect to this issue, the respondents were asked their perception about level of competition in their export markets: whether the competition in the past few years or one decade has become tighter or not (they should answer just 'yes' or 'no'), and how it has impacted their export: decline, constant, or increase. The findings show that from the respondents in the both categories who said that competition has increased, the percentages of those who experienced export increase are lower than those with export decline (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Percentage of Respondent Facing Increasing Competition and the Impact on Their Export

Source; field surveys, 2012

5.2.4: Supports from Government and Private Sector

Final important issue is about supports from government institutions and private organisations, i.e. departments/ministries of trade (I), industry (II), and cooperative and SME (III); R&D institutes (IV); universities (V); chamber of commerce and industry (Kadin; VI); business associations (VII); banks and/or non-bank financial institutions (VIII); state-owned companies (BUMN; IX); and local government (Pemda; X). The respondents were asked the following simple question: whether they have (ever) received supports from those mentioned bodies and if they do, in what forms.

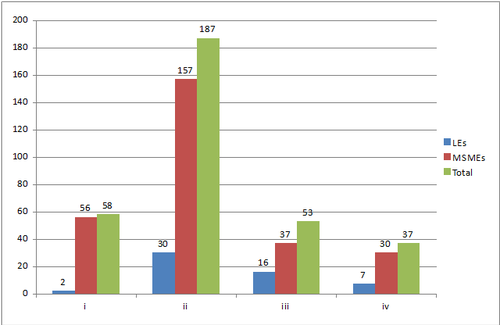

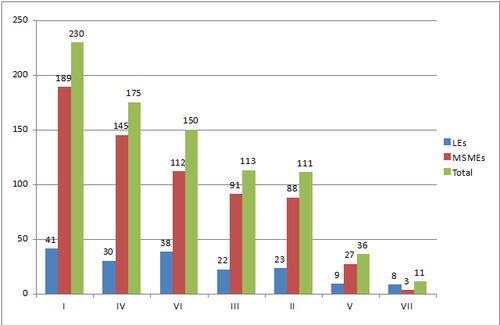

There are at least three most interesting findings, as shown in Figure 11, came out from the respondents' answers to that question. First, in percentage term, there are more respondents from MSMEs than from LEs who have ever received supports or assistances from R&D institutes and universities. While, it is generally expected that R&D institutes and universities are more willing to collaborate with LEs rather than with MSMEs (especially MSEs), at least for two main reasons: (i) it gives more market profitable in the long-run (i.e. more demand opportunities from other LEs to collaborate), and (ii) LEs have enough capital to invest in such collaborations. Second, Indonesian chamber of commerce and industry, and business associations, especially at the regional/local level, are supposed to play a key role in supporting MSMEs, but the fact from the surveys indicates the opposite: more respondents from LEs who enjoyed services/supports from these two private organizations. Third, more respondents from LEs than from MSMEs who have (ever) received financial supports from banks or non-bank financial institutions, and this may suggest obviously that despite government efforts to increase the role of financial institutions in supporting the enterprises, including the introduction in some years ago of a special non-collateral-based credit scheme, known in Indonesia as kredit usaha rakyat (KUR), still many MSMEs in the country have no access to the financial institutions, especially commercial banks.

Figure 11: Percentage of Respondents by Supports Received from Government and Private Sector

66

Source: field surveys 2012

With respect to the form of supports they received, the respondents were given a list of type of supports that they should choose (can be more than one type), i.e. training (I), financing (II), technical aasistance (III), marketing/promotion (IV), procurement of raw materials/inputs (V), market information (VI), and others if any (VII). As shown in Figure 12, based on how many times individual types mentioned by the respondent, training reveals as the most popular form of supports with total frequency of 230 times, and this type of support is also the most important one for MSME respondents (189) than for LE respondents (41). The second important type from the MSME respondents' perspective is marketing/promotion supports, followed in the third place by marketing information. With respect to 'other' types, helping them in applying for export license is the most often mentioned by the respondents.

Figure 12: Frequency of Mentioning the Types of Supports by the Respondents

Source: field surveys 2012

Regarding the role of banks in supporting MSMEs in Indonesia, national data (BPS) 2010 shows that out of 559,971 MSEs in the manufacturing industry which used external sources of finance, only 112,627 used credit from banks, or around 20 percent only. The percentage, however, varies not only by group of industry (Figure 13) but also by province (Figure 14). By group of indusry, the highest percentage is in industries producing other chemical products, which indicates that in this industry group almost all existing MSEs made a use of credits from banks, while, in bacic chemical industry, none of existing MSEs have used that bank facility. By province, what is supprisingly, the province of Papua recorded the highest proportion of existing MSEs having credits from banks. The variation by province can be explained by various factors, including the scatter of locations of MSEs and banks, types of constraints faced by the enterprises and products they made (which determine their need for external capital), and of course, not unimportant, the active roles of local government officials to promote existing credit schemes to local MSEs as well as staffs of local banks to reach local MSEs.

Figure 13: Percentage of MSEs Using Credits from Banks by Industry Group, 2010

Source: BPS (2010).

Figure 14: Percentage of MSEs Using Credits from Banks by Province, 2010

Source: BPS (2010).

Finally, with respect to the role of other non-financial organisations (including government), as a comparison to the findings from the field surveys shown and discussed above, the same BPS data 2010 shows that from a total of 2,732,724 MSEs, only 83,196 enterprises (or around 3 percent) ever received assistances or other types of support from government; 30,697 enterprises (1.1 percent) from private sector (e.g. university, chamber of commerce and industry, business associations), and 8,207 enterprises (0.3 percent) from non-government organisations (NGOs). Of course, the importance of these organisations for MSEs varies not only by group of industry but also by province.

5.2.5 Policies

Export growth of a firm is determined simultaneously by two groups of factors, namely: internal factors such as management, organization of the company, technology owned/used, skills of employees, company strategy, and so on, and external factors. The latter consists of (i) government policies and (ii) non-policy factors such as social, political and economic conditions, national labour force (in quantity as well as quality), availability of raw materials and other necessary inputs, and yet many others. On the other hand, government policies affect export growth of a firm through two channels: direct and indirect. Direct policies are those special designed to affect national export volume of total or certain commodities (e.g. removing export barriers, lowering/eliminating import tariffs of raw materials for export production, issuing of a special credit scheme with subsidized interest rate for exporters). Indirect policies, on the other hand, are those for other areas but have also impacts on export. For instance, adopting expansive fiscal to increase infrastructure certainly will have a positive effect, ceteris paribus, on exporters.

With respect to government policies (e.g. regulations, laws, decisions, or ministries/presidential decrees), the respondents were requested to mention three things: (i) several policies that have positive impact on their export; (ii) several policies that have negative impacts on their export, and (iii) kinds of incentives that they need most to increase their export. During the surveys, many respondents, especially from the MSE category have been found to have difficulties in answer the questions, as many of them were not really aware of existing government regulations which affected directly or indirectly their exports or they have no any idea what kinds of incentives or policies that are good for their export activities. Consequently, many of the respondents from the MSME category did not give clear answers on the questions. Nevertheless, from those who could answer, it reveals a clear picture on 'positive' policies that they need, as presented in Table 6.

Table 6: "Positive" Policies Needed by Respondents

|

Aspects |

"Positive" policies |

|

Raw materials |

-Prohibiting export of raw materials (e.g. rattan) -Facilities to import raw materials for exports, including the presence of safeguard; -Low or no import tariffs -No restriction to import used materials/components -Stable and competitive exchange rate |

|

Product quality |

-Implementation of Indonesian National Standard (SNI) and supports for entrepreneurs to meet SNI |

|

Export activity |

-Supports in the forms of e.g. technical assistance, special credit scheme or easy access to bank credits, training, promotion, market information; -Centralization of export services networks and working 24 hours, including online services to get all licenses required. -No export tax and other barriers -Stable and competitive exchange rate -Low costs of transportation to port/hub, container, shipping |

|

Energy |

-Low cost -Sustainability in supply (e.g. electricity) |

|

Infrastructure |

-Development or improvement of existing infrastructure including road, port/harbor facilities (e.g. Semarang) |

|

Manpower |

-conducive wage regulation |

|

Business environment |

-No sudden changes or inconsistency in regulation/policies -New regulations must be clear and well thought off. |

Source: field surveys

6. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Based on both secondary data and primary data from field surveys in three locations, this study shows four interesting facts about export-oriented MSMEs in Indonesia. First, it is related to the performance of the enterprises, which shows that the enterprises are still relatively weak in doing export. Even, it has been found from the field surveys that many of MSME respondents did not export directly, and this can be explained by the fact that most MSMEs, especially MSEs, in Indonesia lack of necessary inputs including information, capital and skills. Lack of these inputs makes them very hard (if not impossible) to improve their productivity and quality of their products which are two important determinants of level of competitiveness, as well as to do export by themselves.

The second is about main facing MSMEs which are in the areas of marketing, raw materials procurement and capital. As said before, lack of capital, which often said to be caused by their lack of access to formal sources of credit, may also attribute to their marketing difficulties as most of MSMEs, particularly SEs and MIEs, do not have capital enough to explore their own markets.

The third is about their access to TFs, which shows that LEs have more access than MSMEs to TFs, and not knowing or personally uninformed about the existing TFs reveals as the main reason for not having access. This fact from the field surveys is supported by national data which suggests that many MSMEs, especially MSEs, in Indonesia do not make a good use of existing facilities simply because they are not aware that such facilities exist or do not know the procedure.

The fourth interesting fact from this study is about the role of government such as the Ministry of Trade, the Ministry of Industry, and the Ministry for Cooperative and SMEs, and private organizations like Indonesian chamber of commerce and industry, business associations, and commercial banks in supporting MSMEs. It has been found that not all of the MSMEs respondents ever received supports from government (even not from the Ministry for Cooperative and SMEs) as well as from those mentioned private organizations. On the contrary, more respondents from the LE category than from the MSME catgeory who enjoyed services from these private organizations. Also more respondents from LEs than from MSMEs who have (ever) received financial supports from banks or non-bank financial institutions.

These findings have policy implication. Specifically, this study has the following four recommendations:

1) all government departments and other non-department organisations, which have MSMEs development programs or provide services to the enterprises, especially the Ministry for Cooperative and SMEs which is supposed to be the leading department in supporting MSMEs, should review their approaches in reaching potential MSMEs or in providing supports to MSMEs, including in coordination with regional governments, in order to provide equal access to all potential MSMEs in all locations. A good coordination between a ministry and local government offices has become crucial since the implementation of regional autonomy. On the other hand, regional/local governments should take their own initiatives in choosing the best alternative ways to help local MSMEs since, at least theoretically, they know better than Jakarta the real actual conditions and the needs of local MSMEs.

2) from the author's long time experiences, local MSMEs and even local governments often do not know or aware of current programs initiated by central government (e.g. the Ministry for Cooperative and SME); or if the local governments know they have no idea how to implement in their own territories, or if local MSMEs ever heard a particular program, they do not know what they should do to be included in the program. Even, local chamber of commerce and industry or related business associations are sometimes not informed with a particular program currently implemented by the central government. So, regional-wide socialization/promotion of existing programs/services is important, and this can be done effectively and efficiently in the form of collaboration with local private organization such as Indonesian chamber of commerce and industry (Kadinda), business association, universities and NGOs in implementing the programs/services;

3) Government funding from APBN (or from APBD in the case of local government) for supporting MSMEs is not unlimited and credit schemes for the enterprises, including KUR, have high opportunity costs. Therefore, potential MSMEs to receive financial supports should be well-selected and priority should be given first to those which have great export potential. One consequence of this is that the government should increase the maximum amount of KUR beyond Rp 5 millions because doing exports involves larger costs than only servicing local markets.

4) the existing paradigm of MSME development approach/strategy adopted by the central government, which see MSMEs are important mainly because they generate employment and reduce poverty is not relevant anymore in this era of globalization and world trade liberalization. Now, the role of MSMEs should be regarded more as an important (if not the most important) source of national export development and growth, together with their other crucial role, namely as efficient and highly competitive local/domestic suppliers for domestic exporting companies, including LEs, in general. The implication of this new paradigm is that export-oriented MSMEs and those as local suppliers/subcontractors should be given the highest priority above other MSMEs producing simple consumption goods for local markets in receiving all services provided by government.

References

ADB (2002), “Report and Recommendation of the President to the Boards of Directors on a Proposed Loan and Technical Assistance Grant to the Republic of Indonesia for the Small and Medium Enterprise Export Development Project”, ADB RRP: INO 34331, November, Jakarta: Asian Development Bank.

ADB (2009), Key Indicators for Asia and thePacific 2009, Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Alavi, Hamid (2009), “Promoting the Development of SMEs in Times of Crisis: Trade Facilitation and Trade Finance”, paper presented at Regional Policy Forum on Trade Facilitation and SMEs in Times of Crisis, 20-22 May, Beijing, China.

Alburo, Florian A. (2008), “Context of IT in TF”, paper presented at the ARTNeT Research Team meeting on “Impact of IT based Trade Facilitation Measures on Inclusive Development”, July 29-30, Bangkok: UNESCAP

Altenburg, Tilman and J. Meyer-Stamer (1999), “How to Promote Clusters: Policy Experiences from Latin America”, World Development, 27(9).

APEC (2006), “A Research on the Innovation Promoting Policy for SMEs in APEC” Survey and Case Studies”, December, APEC SME Innovation Center, Korea Technology and Information Promotion Agency for SMEs, Seoul.

Bernard, A., and B. Jensen (2004), “Why Do Some Firms Export?” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(2):561–69.

Bernard, A., and J. Wagner (2001), “Export Entry and Exit by German Firms.” Review of World Economics, 137(1):105–23.

Berry, Albert., Edgard Rodriguez and Henry Sandee (2002), “Firm and Group Dynamics in the Small and Medium Enterprise Sector in Indonesia”, Small Business Economics, 18(1–3):141–161.

BPS (2010), Profil Industri Mikro dan Kecil 2010 (profile of micro and small industries), Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik.

Chaney, T. (2005), “Liquidity Constrained Exporters”, paper, University of Chicago, Illinois.

Chaturvedi, Sachin (2006a), “An Evaluation of the Need and Cost of Selected Trade Facilitation Measures in India: Implications for the WTO Negotiations: A Summary”, in Studies in Trade and Investment (STI) No. 57, An Exploration of the Need for and Cost of Selected Trade Facilitation Measures in Asia and the Pacific in the Context of the WTO Negotiations, Bangkok: UN ESCAP.

Chaturvedi, Sachin (2006b). “An Evaluation of the Need and Cost of Selected Trade Facilitation Measure in India: Implications for the WTO Negotiations”, ARTNeT Working Paper No. 4, Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade, Bangkok: UNESCAP.

Chaturvedi, Sachin (2007), “Trade Facilitation Measures in South Asian FTAs: An Overview of Initiatives and Policy Approaches”, ARTNeT Working Paper Series, No. 28, January, Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade, Bangkok: UNESCAP.

Chaturvedi, Sachin (2009),”Impact of IT related Trade Facilitation Measures on SMEs: An Overview of Indian Experience” ARTNeT Working Paper Series, No 66, May, Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade, Bangkok: UNESCAP

Cole, William (1998a), ‘Bali’s Garment Export Industry’, in Hal Hill and Thee Kian Wie (eds.), Indonesia’s Technological Challenge, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, Canberra, and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

Cole, William (1998b), ‘Bali Garment Industry. An Indonesian Case of Successful Strategic Alliance’, mimeographed, Jakarta: The Asia Foundation.

Damuri, Yose Rizal (2006), “An Evaluation of the Need for Selected Trade Facilitation Measures in Indonesia: Implications for the WTO Negotiations on Trade Facilitation”, ARNeT Working Paper Series, No. 10, April, Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade, Bangkok: UNESCAP

De Dios, Loreli C. (2009), “The Impact of Information Technology (IT) in Trade Facilitation on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMES) in the Philippines”, paper presented at the Regional Policy Forum on Trade Facilitation and SMEs in Times of Crisis, 20-22 May 2009, Beijing, China.

De Silva, T.S.A (2007), “Trade Facilitation – Its Implementation in Sri Lanka”, Daily News, 25 May, Colombo.

Edquist, C. (2004), “Systems of Innovation Perspectives and Challenges”, in Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D. and R. Nelson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Innovation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goh, Mark (2007), “High-growth, Innovative Asian SMEs for International Trade and Competiitveness: Challenges and Solutions for APO Member Countries”, Tokyo: Asian Productivity Organization.

Grainger, Andrew (2009), “Customs and Trade Facilitation: From Concepts to Implementation”, World Customs Journal, 2(1): 17-30.

Greenaway, D., A. Guariglia, and R. Kneller (2007), “Financial Factors and Exporting Decisions”, Journal of International Economics, 73(2):377–95.

Hakim, Dedi Budiman (2007), “Dampak ASEAN Trade Facilitation Terhadap Daya Saing Daerah” (the impact of ASEAN trade facilitation on the regional competitiveness), Seminar Paper, December, Department of Economic Science, Faculty of Economics and Management, Institut Pertanian Bogor, Bogor.

Hill, Hall (2001a), “Small and Medium Enterprises”, Indonesia Asian Survey, 41(2): 248-270.

Hill, Hal (2001b), “Small and Medium Enterprises in Indonesia: Old Policy Challenges for a New Administration”, Asian Survey 41(2): 248-70.

IMD (2008), “Entrepreneurship and Trade facilitation in Bangladesh: Unleashing the potentials of SMEs in a Regional Context”, Interim Report, Geneva Trade and Development Forum, Geneva.

Ito, Hiro and Akiko Terada-Hagiwara (2011), “Effects of Financial Market Imperfections on Indian Firms‘ Exporting Behavior”, ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 256, May, Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Jinadasa, A. (2008), “Automated Cargo Clearance will cut import, export costs”, The Sunday Times, Financial Times, sundaytimes.lk/080615/FinancialTimes/ft331.html

Kumar, S. (2006), “WTO Trade Facilitation Negotiations in Sri Lanka”, www.unescap. org/tid/ artnet/mtg/tfri_sl.pdf

Li, Z., and M. Yu (2009), “Exports, Productivity, and Credit Constraints: A Firm-Level Empirical Investigation of China”, Global COE Hi-Stat Discussion Paper Series #098, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo.

Loebis, L. and Schmitz, H. (2005), “Java Furniture Makers: Globalisation winners or losers?, Development in Practice, 15(3-4):514-521.

Long, Nguyen Viet (2003), “Performance and obstacles of SMEs in Viet Nam Policy implications in near future”, reseach paper, International IT Policy Program (ITPP) Seoul National University, Seoul.

Macasaquit, Mari-Len Reyes (2009), “Trade Facilitation in the Philippines and the SME Factor”, paper presented at the Regional Policy Forum on Trade Facilitation and SMEs in Times of Crisis, 20-22 May 2009, Beijing, China.

Manova, K. (2009), “Credit Constraints, Equity Market Liberalizations, and International Trade”, Journal of Internatinoal Economics,76:33–47.

Milner, Chris, Oliver Morrissey and Evious Zgovu (2009), Trade Facilitation in Developing Countries”, CREDIT Research Paper No.08/05, Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade, University of Nottingham.

Miranti, Ermina (2007), “Observing Performance of Indonesian Textile Industry: Between Potency and Oppirtunity”, Economic Review, no.209, September.

MoCI (2008), “eTrade: Facilitating International Trade in India”, paper, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, New Delhi.

Mohanty, S. K. and Robert Arockiasamy (2008). “Prospects for making India’s manufacturing sector export oriented”, Ministry of Commerce and Research & Information System for Developing Countries, New Delhi.

Moïsé, Evdokia (2004). The costs of introducing and implementing trade facilitation measures: interim report (Document TD/TC/WP(2004)36/FINAL). Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Moïsé, Evdokia, T. Orliac and P. Minor (2011), “Trade Facilitation Indicators: The Impact on Trade Costs”, OECD TradePolicy Working Papers, No. 118, OECD Publishing, Paris: Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development,

Muúls, M. (2008), “Exporters and Credit Constraints. A Firm Level Approach”, paper, Bank of Belgium, Brussels.

Novrial Anas (2003). “Indonesian Customs Reform Comprehensive Measures For Facilitating Legal Trade”. paper presented in The Third ASEM Seminar on the Simplification and Harmonization of Customs Procedures, Jakarta.

OECD (2003), “Quantitative assessment of the benefits of trade facilitation, Working Party of the Trade Committee”, OECD, Paris.

Rahardhan, Perdana, Adi Kusumaningrum and Fuad Aulia Rahman (2008), :Pengaruh ASEAN Trade Facilitation Terhadap Volume Perdagangan Produk Unggulan Jawa Timur” (Effect of ASEAN Trade Facilitation on the Trade Volume of Favored Commodities from East Java), study report, Surabaya.

Roy, Jayanta (2004), “Trade Facilitation in India: Current Situation and the Road Ahead”, paper presented at the EU-World Bank/ BOAO Forum for Asia Workshop on “Trade Facilitation in East Asia”, Beijing, 3-5 November.

Sandee, Henry (1995), “Innovation Adoption in Rural Industry: Technological Change in Roof Tile Clusters in Central Java, Indonesia”, unpublished PhD dissertation, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam.

Sandee, Henry and J. ter Wingel (2002), “SME Cluster Development Strategies in Indonesia: What Can We Learn from Successful Clusters?”, paper, JICA Workshop on Strengthening Capacity of SME Clusters in Indonesia, 5-6 March, Jakarta.

Sengupta, Nirmal and Moana Bhagabati (2003), “A Study of Trade Facilitation Measures: From WTO Perspective”, paper, August, Madras Institute of Development Studies, Chennai.

Shahid, Yusuf (2007), “From Creativity to Innovation” Policy Research Working Paper 4262, June, Development Research Group, World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Shepherd, Ben and John S. Wilson (2008), “Trade Facilitation in ASEAN Member Countries: Measuring Progress and Assessing Priorities”, Policy Research Working Paper 4615, May, The World Bank Development Research Group Trade Team, Washington, D.C.

Son, Nguyen Hong and Dang Duc Son (2011), “Improving Accessibility of Financial Services in the Border-Gate Areas to Facilitate Cross-Border Trade: The Case of Viet Nam and Implications for Greater Mekong Subregion Cooperation”, Research Report Series, 1(4), October, Greater Mekong Subregion–Phnom Penh Plan for Development Management, Manila: Asian Development Bank.