2013—The 7th China-ASEAN Forum Poverty1

Introduction

Urbanization is the historical process of the gradual transformation from a traditional agriculture-based rural society to an industry and service-oriented modern urban society. Generally speaking, the higher the level of total economy and urbanization, the lower the poverty rate is. In some countries, however, with rapid urbanization, more urban residents have fallen into poverty, resulting in social instability. Therefore, a major issue worthy of study is how to take full advantage of the dynamic mechanisms for urbanization-based poverty reduction to gradually reduce poverty associated with the advance of urbanization. In particular, China and most ASEAN countries have just entered the ranks of middle-income countries and are undergoing rapid urbanization, so it is of greater importance to coordinate urbanization and poverty reduction.

According to 2011 data of Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the global urbanization rate is 52.1%, the urbanization rate of developed countries is 77.7%, that of underdeveloped countries is 46.5%, and that of the least developed countries and regions is only 28.5%. From a regional perspective, the urbanization rate is 82.2%, 79.1%, 72.9%, 70.7%, 45% and 39.6% respectively in North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe, Oceania, Asia and Africa. From the perspective of a single country or region, based on the degree of urbanization, among the 243 countries or regions (excluding two without relevant data), 37 countries have an urbanization rate of 60-70%, 16 countries have an urbanization rate of 10-20% and 31 have an urbanization rate of more than 90%.

Now, let us take a look at the situations in 10 ASEAN countries. The urbanization rate averages about 44.7% in 10 ASEAN countries: 70-100% in Singapore, Brunei and Malaysia, 60% in Indonesia, 40-50% in the Philippines, 30-40% in Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar, and 20-30% in Cambodia. The urbanization rates are generally low, below the global average of 52.1%. In China, this rate is also only 50.6%. In the next period, therefore, urbanization will still be a development trend of the majority of ASEAN countries and China.

With the process of urbanization, involving different stages of economic and social development, the poverty situations and anti-poverty policies of various countries are constantly changing. This is because urbanization itself has not only a positive but also a negative impact on rural and urban poverty. Figuratively speaking, urbanization is a means of poverty reduction, but may also become a cause of poverty.

First, changes have taken place in the distribution of poverty in urban and rural areas. Rural people flow into the city in search of employment and earn income in the city, increasing the income of rural households, thereby reducing rural poverty. It has become the most important means for many countries to reduce rural poverty. As many rural residents flow into the city, the urban economy flourishes, therefore playing a positive role in urban poverty reduction. After rural residents move into the city, however, they cannot enjoy the urban public services and public facilities, have poor working and living conditions and are treated unequally. In accordance with the urban living standard and poverty line, most of them are poor, thus increasing the scale of urban poverty. Even the farmers who lived outside the city and lost their land due to urbanization will probably become the new urban poor as they lack the competitiveness for urban employment. Meanwhile, due to the migrant work of these rural residents, many children and elderly people are left in the countryside and there are a smaller number of rural laborers in rural areas, deepening the poverty of the left-behind children and elderly people. Therefore, it is very difficult to further reduce poverty in rural areas.

Second, urban poverty is getting increasing attention in the process of urbanization and urban anti-poverty policy has been gradually improved. Studies have shown that the harm of urban poverty is more serious than that of rural poverty. In recent years, for example, protest marches , violence and even terrorism frequently occur in many countries due to an increase in unemployment. Therefore, while attaching importance to rural poverty reduction, governments around the world, especially governments of developing countries, have begun to pay close attention to urban poverty reduction. The urbanization rate in Latin America and the Caribbean is up to 79.1%. These countries have experienced urbanization of poverty in the process of rapid urbanization, i.e. the transfer of rural poverty-stricken people to the city. To address the high incidence of urban poverty, in the past two or three decades, these countries have developed relatively strong urban poverty reduction strategies, policies and measures, among which the conditional cash transfer and community upgrade plan (slum upgrading program) are two pillar policies for urban poverty reduction. Of course, according to World Bank data, except for Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei, which have a relatively high urbanization rate and low poverty rate, the urban poverty rates of all other ASEAN countries are relatively high in the process of urbanization. For example, the poverty rate has reached 26.5% (2009) in the Philippines, 17.4% (2008) in Laos, 12.5% (2011) in Indonesia and 13.2% (2011) in Thailand. With the advance of urbanization, rural poverty may rapidly transform into urban poverty. Therefore, the governments of these countries, which are still in the process of urbanization, need to pay attention to urban poverty and quickly adopt relevant policies and measures to cope with urban poverty. At the same time, we should also pay attention to the poverty in the flow and the impact of urbanization on rural poverty. In China, the urbanization process is still accelerating. Although the Chinese government has comprehensive rural poverty reduction strategies and measures and has adopted a series of policies and measures to cope with urban poverty, not so many measures have been developed to deal with the problem of poverty caused by a floating population in the process of urbanization and it is difficult to cope with the poverty problem caused by urbanization.

This report is mainly about poverty in the process of urbanization. In the process of urbanization, poverty takes three forms, namely urban poverty, poverty of migrants and rural poverty. Among them, rural poverty mainly refers to the poverty caused by urbanization, such as the poverty of left-behind children and elderly people. From a gender perspective, it may also include the problem of left-behind women in rural areas. This report is written to provide discussion materials for the Seventh China-ASEAN Forum on Social Development and Poverty Reduction and serve as a more in-depth discussion on poverty in the process of urbanization. We hope this report will raise awareness of poverty in the process of urbanization, summarize the experiences and lessons of the international community in effectively addressing and responding to the poverty problem caused by urbanization, and help affected countries further improve their anti-poverty strategy and policy systems.

Due to the limitations of the authors’ professions and limited understanding of relevant materials, except for the literature review chapter, which is written from a global perspective, and the chapter on urbanization and poverty in Southeast Asian countries, which is written from the perspective of Southeast Asian countries, the remaining chapters are all based on the example of China. Therefore, taking China as an example, this report focuses on analysis and discussion of China’s poverty in the process of urbanization, and finally puts forward solutions to the poverty problem caused by urbanization in China.

This report consists of four parts. Part I (Chapter 1) mainly studies the relevant literature on urbanization and poverty and summarizes the findings of studies on urbanization and poverty, aiming at making clear the relationship between urbanization and poverty, the problems caused by urbanization and the way to deal with the problems. This comprises all of Part I. Taking China as an example, Part II mainly studies the poverty problem in the process of urbanization. In China, the problem of poverty is closely linked to urbanization. Part II consists of five chapters. Chapters 2 and 3 are on urban poverty. The reports analyze the poverty of urban residents from the perspectives of income poverty and multidimensional poverty. Chapter 4 addresses the poverty of the floating population. It discusses in detail the poverty of the floating population, which is a special kind of poverty caused by China's dual urban-rural system. Chapters 5 and 6 discuss the poverty of left-behind rural people caused by urbanization, specifically the poverty of left-behind children and elderly people. Part III (Chapter 7) is mainly about the urbanization and poverty of ASEAN countries as a summary study. Comments of participants from the ASEAN countries are welcomed to better serve the forum. Part IV (Chapter 8) puts forward the strategy for the integrated development of urban and rural areas and poverty reduction, mainly for China’s pro-poor strategies and system, which are characterized by the separation of urban and rural areas. That is to say, in China, urban poverty reduction does not take the floating population into account, and rural poverty reduction also excludes migrants. Such a framework seems fairly complete, but it inevitably ignores some problems, such as changes in the poverty situation of landless peasants.

Authors of this report: Introduction by Zhang Deliang; Chapter 1, Urbanization and Poverty: Literature Review and Conceptual Framework, by XIA Qingjie and WANG Dashu ; Chapter 2, Income Poverty of China’s Urban Residents (1989-2011), by WANG Xiaolin and ZHANG Deliang; Chapter 3, Multidimensional Poverty of China’s Urban Residents (1989-2011), by ZHOU Liang and WANG Xiaolin; Chapter 4, Social Exclusion of China’s Floating Population, by WANG Xiaolin and ZHANG Lu ; Chapter 5, Poverty and Protection of Left-behind Children in Rural Areas in the Context of Urbanization, by ZHANG Xiaoying, GAO Rui and WANG Erfeng; Chapter 6, Poverty and Protection of Left-behind Elderly People in Rural Areas, by XU Liping and WANG Erfeng; Chapter 7, Urbanization and Poverty: Experience of the ASEAN Countries, by LIU Qianqian; Chapter 8, Challenges for China’s Anti-poverty Policy System in the Process of Urban-rural Integration, by LIN Wanlong.

Chapter 1: Urbanization and Poverty: A Literature Review of the Concept and Framework

XIA Qingjie, WANG Dashu

(School of Economics, Peking University)

1. Introduction

The most profound transformation in human history has been the change of technology and means of production. Nearly all developing countries are still in the stage of transformation from agriculture to industrialization. In the agrarian phase, the basic productive units are agricultural households, and hence the economic activities are scattered across the countryside. In contrast, in the process of industrialization, the basic productive units are enterprises. To achieve the advantages of mass production and to sell what is produced, industrial firms have to be located in urban areas where workers live and markets are located, and consequently industrial economic activities cluster in urban cities. Urbanization involves major shifts in the ways people work and live, and offers unprecedented opportunities for improved standards of living, higher life expectancy and higher literacy levels, as well as better environmental sustainability and a more efficient use of increasingly scarce natural resources. For the majority of people, and in particular for women, urbanization is associated with greater access to employment opportunities, lower fertility levels and increased independence. However, urbanization does not necessarily result in a more equitable distribution of wealth and wellbeing. In many low and middle-income nations, urban poverty is growing compared to rural poverty.

Specific aspects differentiate urban poverty from rural poverty. While urban residents are more dependent on cash income to meet their essential needs, income poverty is compounded by inadequate and expensive accommodation, limited access to basic infrastructure and services, exposure to environmental hazards and high rates of crime and violence. Therefore, urban poverty is not only income or consumption poverty although income or consumption poverty still occupies the most important place in the dimensions of poverty measurement. In addition to food and shelter, human beings need education, health care, and a suitable living environment (Sen, 1985 and 1999). As a result, urban poverty has to be studied and measured from multidimensional perspectives (Wang and Alkire,2009). The Poverty Relief Office of the State Council (2011-2020) in light of this, we use the methodology of multidimensional poverty measurement as the guidelines when reviewing the literature on urbanization and poverty.

The rest of the chapter is as follows. Section 2 is the key part of the chapter; it includes the theoretical analysis and a discussion of urbanization and slums, urbanization and the living environment of urban poor, the redevelopment of housing for urban poor in Chicago in the U.S., and general issues of urbanization and poverty. In Section 3 we review literature on the relationship between terrorist activities and urbanization. Section 4 is focused on urbanization and rural poverty. Section 5 is on Chinese urbanization and poverty. Section 6 is a summary.

2. Urbanization and Poverty

2.1 Theoretical models on urbanization and poverty

Martinez-Vazquez et al. (2009) examines the impact of urbanization on poverty in theory. They find a U-shape relationship between the level of urbanization and poverty. Urbanization contributes to poverty reduction but at much higher levels. They also provide empirical evidence for their model by econometric data analysis.

Ravallion (2002) developed a simple model of urbanization of the poor in a developing country. Under this model, conditions have been identified under which the poor urbanize faster than the non-poor, implying that the urban share of the poor is an increasing convex function of the urban share of the population. This is found to be consistent with cross-sectional data for 39 countries and time series data for India. However, the estimated empirical model suggests that the urban poverty rate rises slowly relative to the rural rate. It is predicted that 60% of the poor will still live in rural areas by the time half the population of the developing world lives in urban areas.

Sato (2005) develops a model of endogenous fertility with two sectors (urban and rural) and analyzes the relationship among urbanization, fertility rate determination, and economic development. In the model, technological progress and human capital accumulation are complementary. The urban sector is assumed to have better opportunities for education and more human capital-intensive production technology than the rural sector. A poverty trap is shown to exist, in which the economy has no human capital accumulation and no technological progress. Once the economy takes off from the poverty trap, human capital accumulation and technological progress advance, and the economy reaches an endogenous growth path. In order for the economy to take off from the poverty trap and begin economic development, sufficiently high human capital and technology levels are shown to be necessary.

2.2 Urbanization and Slums

In developing countries the level of urbanization is expected to increase to 56.9% by 2025. The number of people living in slums and shanty towns represents about one-third of the people living in cities in developing countries. Harpham and Stephens (1991) study poor urban populations, their lifestyles and their exposure to hazardous environmental conditions which are associated with particular patterns of morbidity and mortality. The concept of marginality has been used to describe the lifestyles of the urban poor in developing countries. This concept is critically examined and but the result is rather vague. However, it can certainly be claimed that in health terms the urban poor are marginal. Most studies of the health of the urban poor in developing countries concentrate on the environmental conditions in which they live. However, other aspects of their ways of life, or lifestyles, have implications for their health. Issues such as smoking, diet, alcohol and drug abuse, and exposure to occupational hazards, have received much less attention in the literature and there is an urgent need for more research in these areas.

Accompanying this rapid pace of urbanization has been a faster growth in the population residing in slums. It is estimated that the slums represent the fastest growing segments of the urban population at about 5-6 per cent per annum (Chatterjee, 2002). This is double the growth rate of the overall urban population. Slums are characterized by crowded living conditions, unhygienic surroundings and a lack of basic amenities such as garbage disposal facilities, water and sanitation. The near total absence of civic amenities coupled with the lack of primary health care services in most of the urban poor settlements have an adverse impact on the health status of their residents. The health of the urban poor is significantly worse than that of the rest of the urban population and is often comparable to the health conditions in rural areas (Agarwalet al., 2007).

Chandrasekhar and Montgomery (2010) find that substantial percentages of urban Indian households live in housing that falls well short of meeting basic needs, especially in non-notified 'slum' communities, although officially they live above the poverty line. Poverty lines in India have been established with some allowances for basic nutritional needs, but have neglected basic needs in housing. In urban areas, expenditures on housing take up a sizable share of household budgets, even without adjustments for the quality and adequacy of accommodations. Therefore, the Indian urban poverty line has to be revised by considering the basic housing needs of urban residents, in particular the urban poor.

One of the most enduring physical manifestations of urban poverty in Africa is the proliferation of slums and squatter settlements. About 62% of the urban population in sub-Saharan Africa resides in slums. These settlements have the most deplorable living and environmental conditions characterized by inadequate water supply, squalid conditions of environmental sanitation, breakdown or non-existence of waste disposal arrangements, overcrowded and dilapidated habitation, hazardous locations, insecurity of tenure, and vulnerability to serious health risks. Arimah (2011) finds the differences in the prevalence of slums among African countries using data drawn from the global assessment of slums by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT). The empirical analysis identifies substantial inter-country variations in the incidence of slums; it also indicates that higher levels of income, greater financial stability and investment in infrastructure will reduce the incidence of slums. Conversely, the external debt burden, high levels of inequality, unplanned and unmanaged urban growth, and the exclusionary nature of the regulatory framework governing the provision of residential land contributes to the prevalence of slums and squatter settlements.

Lanrewaju et al. (2012) investigate the housing quality in Nigerian cities and the impacts of urbanization on environmental degeneration of the urban built environment. They identifies the problems that have aided the degeneration as: inadequate basic infrastructural amenities, substandard housing, overcrowding, poor ventilation in homes and work places, and noncompliance with building bye-laws and regulations. They find that the poor housing quality has serious adverse effects on the environment and the health of city residents. Strategies for improving the built environment for sustainable living are suggested. Therefore it is imperative to check and prevent further decay for harmonious living and sustainable developments.

As UN-HABITAT (2010b, p. 33) has reported:

Asia was at the forefront of successful efforts to reach the Millennium slum target between the year 2000 and 2010, with governments in the region improving the lives of an estimated 172 million slum-dwellers; these represent 75% of the total number of urban residents in the world who no longer suffer from inadequate housing. The greatest advances in this region were recorded in Southern and Eastern Asia, where 145 million people moved out of the ‘‘slum-dweller’’ category (73 million and 72 million, respectively); this represented a 24% decrease in the total urban population living in slums in the two sub-regions. Countries in South-Eastern Asia have also made significant progress with improved conditions for 33 million slum residents, a 22% decrease.

How did some Asian countries beat the Millennium slum target? Public authorities used five complementary approaches: (i) awareness and advocacy, (ii)long-term political commitment, (iii) policy reforms and institutional strengthening, (iv)proper implementation and monitoring, and (v) scaling up of successful local projects (UN-HABITAT, 2010b). At city level, interventions for slum upgrading focused on citywide pro-poor policy and strategy making (DahiyaandShagdarsuren, 2007), as well as physical improvements. Despite this spectacular progress, the Report is a reminder that the Asia–Pacific region remains host to 505.5 million slum dwellers (2010) – over half of the world’s slum population – and this is a major challenge for Asian cities (Dahiya 2012). Behind Asia’s abundant slums is the problem of poor access to decent, secure, and affordable land, the lack of adequate low-income housing, and the consequent overcrowding. Moreover, informal settlements suffer from the inadequate provision of basic services, such as potable water, sanitation, waste collection, energy, transportation and health care (Dahiya,2012).

In many Asian countries, housing does find a prominent place in national policies. However, the public resources devoted to housing construction, especially for low-income populations, remain well short of requirements. To respond to the massive demand for housing, Asian countries have made use of five main institutional models. (i) In their vigorous pursuit of slum-free cities, public housing policies and projects have been implemented in Singapore, the Republic of Korea, and Hong Kong. In Singapore, the Housing Development Board has provided housing for 85% of those who live in high-rises. An estimated 92% of these residents are homeowners, while the remaining 8% live as tenants (Jooand Wong, 2008). (ii) Several Asian cities have established public–private partnerships to stimulate affordable housing construction for the poor. In most cases, private sector enterprises have been granted commercial development rights on plots where they would build, quid pro quo, affordable housing on a specified percentage of the total land under development. Notable examples include the revitalization of the rivers Fu and Nan in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China (Wang, 2001); the AshrayaNidhi (‘shelter fund’) program in Madhya Pradesh, India (ASCI – Centre for Good Governance, 2006); and Indonesia’s housing policies whereby private developers build a minimum of three middle-class houses and six basic or very basic ones for every high-cost house (Zhu, 2006). (iii) Many Asian governments have enabled private sector housing delivery for low-income groups. However, this has had mixed results as formal private sector housing tends to favor the high(er)-income groups, a problem partly caused by the ‘inelastic’ supply of serviced land, which, in turn, results in an overall rise in property prices and makes it difficult for real-estate developers to meet demand for low-income housing. (iv) The overall share of rental housing in Asian cities is estimated at 30% of the housing market (Kumar, 2001). However, few governments give effective support to rental housing. When housing is privately owned, the bulk of rental housing accommodates low-income households through informal and flexible lease arrangements. Although it entails lower rents, the weaker security of tenure and (probably) lower quality of public amenities remain significant challenges. (v) Asia has pioneered what has come to be known as the ‘people’s process’ of housing and urban upgrading, spearheaded by dedicated civil society groups, with technical support provided by UN agencies, namely UN-HABITAT and the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Civil society groups, such as Slum Dwellers International and the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, are strong in the region and have gained ground in many cities in cooperation with urban grassroots and community-based organizations. The ‘people’s process’ of housing and urban upgrading is practiced in several cities in Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Thailand (Dahiya, 2012).

The problems in the growth of housing finance for the urban poor in Asia are common to those found in other developing regions. Poor households in Asian cities lack the regular incomes that many mortgage lenders demand. Due to high operational costs, housing finance agencies are unwilling to seek out clients for small loans. Nevertheless, many formal housing finance institutions have sought to ‘down-market’ through mediation by micro-finance institutions or non-governmental organizations. However, high operational costs limit the reach of such programs. The underdevelopment of housing finance for the urban poor in Asia reflects the structural weakness in domestic capital markets, distortions in the legal and regulatory frameworks, and poor familiarity with housing finance and mortgage lending (Dahiya,2012; Bestaniand Klein,2005).

2.3 Urbanization and the Living Environment of Urban Poor

Dunn (2010) argues that green infrastructure is an economically and environmentally viable approach for water management and natural resource protection in urban areas. Besides, green infrastructure has additional and exceptional benefits for the urban poor which are not frequently highlighted or discussed. When green infrastructure is concentrated in distressed neighborhoods—where it frequently is not—it can improve urban water quality, reduce urban air pollution, improve public health, enhance urban aesthetics and safety, generate green collar jobs, and facilitate urban food security. To make these quality of life and health benefits available to the urban poor, it is essential that urban leaders remove both legal and policy barriers to implementing green infrastructure projects. Overcoming these obstacles requires quantified methods and regulatory reform.

Dahiya (2012) divides the urban basic service into six aspects:

a. Water supply: Access to water supply improved in most Asian–Pacific cities between 1990 and 2008, and most countries in the region are likely to achieve the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) for water supply. 2008 data show that the East and North-East Asia sub-region has forged ahead in the provision of water supply, serving 98% of its urban population, and is closely followed by South Asia (95%) and South-East Asia (92%: see WHO and UNICEF 2010). The WHO and UNICEFReport highlights two issues that need policy attention. (i) 4–8% of the urban population remain persistently deprived of access to water supply in most sub-regions, except East and North-East Asia; this suggests that despite overall improvement in service extension, a ‘last mile’ effort is necessary to ensure universal access to these services. (ii) The share of the urban population with access to drinking water declined by 3–12% in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Myanmar and Nepal during 1990–2008, which implies that national and local governments need to keep up the pace of providing basic services to the increasing urban populations (Dahiya, 2012).

b. Sanitation: During 1990–2008, many Asian–Pacific countries made considerable progress in providing access to improved sanitation. Oceania led other sub-regions in access to improved sanitation (defined as improved facilities) for 81% of its urban population, followed by South-East Asia (79%), East Asia (61%), and South Asia (57%) (WHO and UNICEF, 2010). In many cities, the lack of access to safe sanitation is remedied to some extent through increased reliance on shared household facilities. 2008 data show that with the inclusion of ‘shared facilities’, the proportion of urban populations with access to improved sanitation is higher: 91% in East Asia, 89% in South-East Asia, 77% in South Asia, and 81% in Oceania (WHO and UNICEF, 2010). However, the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation raises serious concerns over two aspects of ‘shared facilities’: effective access throughout the day, and security of users, especially at night (UNICEF and WHO, 2008). Due to their limited accessibility, the Millennium targets do not consider ‘shared facilities’ as acceptable. In view of these issues, many Asian–Pacific countries are likely to miss the Millennium sanitation target (Dahiya, 2012).

c. Solid waste management: Though the urban poor in Asia generatelesser amounts of solid waste than their counterparts in higher-income countries, solid waste management systems tend to neglect them for various reasons: (i) urban poor often live in congested areas that are often inaccessible for garbage trucks, (ii) it is difficult to organize urban poor communities to collect their solid waste, (iii) due to few recyclables, private businesses and informal sector waste recyclers do not find it profitable to sort through the waste generated by the urban poor, (iv) as the garbage generated by the urban poor is wet and smelly, it is considered onerous or even hazardous to collect it, and (v) due to their low incomes, the urban poor are unable or reluctant to pay for waste collection services (Laquian, 2004). Besides consuming fewer non-food items and generating lower quantities of solid waste, the urban poor play an important role in solid waste management as they routinely collect, sort, recover, re-use and recycle waste, as 20–30% of their solid waste is recyclable. Dahiya argues that since informal sector participation in solid waste collection and disposal saves significant amounts of funds for local authorities, the latter and private sector enterprises should support the initiatives and efforts deployed by informal sector and community-based organizations to improve solid waste management at the local level (Dahiya, 2012).

d. Health: The urban poor live in deprived urban settings such as underserviced informal settlements or slums, and due to their hazardous locations and unhygienic conditions, often constitute the single largest group of vulnerable populations in Asian–Pacific cities.

Compelling evidence links various communicable and non-communicable diseases, injuries and psychosocial disorders to the risk factors inherent to unhealthy living conditions, such as faulty buildings, defective water supplies, substandard sanitation, poor fuel quality and ventilation, lack of refuse storage and collection, or improper food and storage preparation, as well as poor/unsafe locations, such as near traffic hubs, dumpsites or polluting industrial sites (UN-HABITAT, 2010a, p. 151; see Mercado et al., 2007; UN-HABITAT, 2010b)

The health impacts of such unhealthy living conditions in Asia are evident. In Ahmedabad, infant mortality rates are twice as high in slums as the national rural average in India, and slum children under five suffer and/or die more from diarrhea or acute respiratory infections than those in rural areas. In Manila, infant mortality rates in slums are triple those in non-slum areas (Fry et al., 2002; Dahiya, 2012).

Cities offer the lure of better employment, education, health care, and culture; they also contribute disproportionately to national economies. However, rapid and often unplanned urban growth is often associated with poverty, environmental degradation and population demands that outstrip service capacity. These conditions place human health at risk. Data that are available indicate a range of urban health hazards and associated health risks: substandard housing, crowding, air pollution, insufficient or contaminated drinking water, inadequate sanitation and solid waste disposal services, vector-borne diseases, industrial waste, increased motor vehicle traffic, stress associated with poverty and unemployment, among others (Moore et al., 2003).

The urban character of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa exacerbates concern about the urbanization–poverty relationship. Recent empirical work has linked urban poverty, and particularly slum residence, to risky sexual behavior in Kenya’s capital city, Nairobi. Greif et al. (2011) investigate the generalizability of these assertions about the relationship between urban poverty and sexual behavior using Demographic and Health Survey data from five African cities: Accra (Ghana), DaresSalaam (Tanzania), Harare (Zimbabwe), Kampala (Uganda) and Nairobi (Kenya). They find that, although risky behavior varies across the five cities, slum residents demonstrate riskier sexual behavior compared with non-slum residents. There is earlier sexual debut, lower condom usage and more multiple sexual partners among women residing in slum households regardless of setting, suggesting a relatively uniform effect of urban poverty on sexual risk behavior.

Zulu et al. (2011) find that while slum populations are highly mobile, about half of the population comprises relatively long-term dwellers who have lived in slum settlements for over 10 years. The poor health outcomes that slum residents exhibit at all stages of the life course are rooted in three key characteristics of slum settlements: poor environmental conditions and infrastructure; limited access to services due to lack of income to pay for treatment and preventive services; and reliance on poor quality and mostly informal and unregulated health services that are not well suited to meeting the unique realities and health needs of slum dwellers. Consequently, policies and programs aimed at improving the wellbeing of slum dwellers should address comprehensively the underlying structural, economic, behavioral, and service-oriented barriers to good health and productive lives among slum residents. As urban slum settlements continue to grow in sub-Saharan Africa, the wellbeing of urban residents in general, and of the urban poor in particular, will increasingly shape national indicators on health, poverty, and other development issues. Constructive and sustainable urbanization could help propel Africa out of its perennial underdevelopment quagmire, as it has done in developed countries and the emerging middle-income countries around the globe. However, Africa’s urban tipping point (which is set to take place in 2035 according to UN-HABITAT’s 2010 projections) would turn into a curse if the prevailing urbanization decay characterized by poor governance and planning, poor infrastructure and basic amenities, growing poverty, and deteriorating health outcomes is not compellingly and sustainably addressed.

Although such negative outcomes may appear inevitable, urban areas can promote major health improvements even for low-income households (as has occurred in high-income nations). Medical centers, infrastructure and health personnel are often concentrated in urban areas, while economies of scale and proximity can facilitate good quality provision of water, sanitation, drainage and health care at lower cost (Sverdlik, 2011).

e. Energy: The International Energy Agency estimates that in 2009, 675 million people in developing Asia had no access to electricity (IEA, 2011). In the same year, the urban electrification rate in developing Asia stood at 94%, with 96.4% in China and East Asia and 89.5% in South Asia. Low-income communities are poorly served by energy systems due to a variety of reasons including insecure land tenure, shared spaces, ill-defined responsibilities for payment, and low consumption. Moreover, the urban poor often pay high prices both for relatively poor kerosene-based light and low-quality biomass cooking fuels. Slum dwellers are frequently ignored and bypassed in favor of rural populations despite their active participation in urban economic growth (Modi et al., 2005). Dahiya underlines one lesson for the power sector: the regulation of service providers – local utilities or authorities – should focus on servicing all residents and start viewing the urban poor as potential clients (Dahiya, 2012). Jorgenson et al. (2010) find that from 1990 to 2005, growth in energy consumption was positively associated with growth in the overall urban population and negatively associated with growth in the percentage of a population residing in urban slum conditions. In other words, the negative association between energy consumption and the proportion of the total population living in urban slum conditions in less developed countries is largely a consequence of the limited opportunities and extreme poverty experienced by much of humanity.

f. Urban transport: The urban poor in Asia, as in other regions, need easy, affordable access because they cannot afford land or housing close to their workplaces or motorized vehicles. Inadequate urban and transport planning has caused a decline in spaces for walking and bicycling – Asia’s two traditional modes, in many cities. Asian cities need efficient public transport, especially due to their higher population densities, but they fare worse than their counterparts in developed countries. An increasing number of Asian cities have begun to realise the importance of mass transit and are now making it a policy focus instead of improving vehicle flows. Several cities have deployed bus, skytrain and underground networks to cater to the needs of a larger public, but a good many of those on low incomes cannot even afford public transport. This points out to an urgent need to promote sustainable schemes based on affordable, environmentally-friendly, motorised and non-motorised transport (UN-HABITAT, 2010a, p. 18; Dahiya, 2012).

2.4 Redevelopment of Chicago’s public housing

Chaskin (2013) investigates the reform of public housing for the urban poor. Much contemporary policy seeking to address the problems of urban poverty and the failures of public housing focuses on deconcentrating poverty through the relocation of public housing residents to less-poor neighborhoods or by replacing large public housing complexes with mixed-income developments. Lying behind these efforts is a set of generally integrationist goals, aiming to remove public housing residents from contexts of isolation and concentrated disadvantage and settle them in safer, healthier, and more supportive environments that better connect them to resources, relationships, and opportunities.

The mixed-income development component of Chicago’s Plan for Transformation has generated remarkable change in neighborhoods that had been dominated by large concentrations of public housing. The high-rise developments are gone, and the neighborhoods emerging in their wake are dramatically different environments—cleaner, more orderly, better maintained, safer, and more peaceful—than the public housing complexes they have replaced. Relocated public housing residents moving to these contexts thus benefit from their return in some important ways, enjoying better housing in attractive neighborhoods; reduced stress in light of the increased safety and security of their new surroundings; and—for some—positive changes in their aspirations, motivation, and sense of possibility to improve their lives (Joseph and Chaskin, 2010).

For most, however, these benefits have not included effective integration, entailed the breaking down of ‘social barriers,’ or led to the broader benefits that are meant to come from such integration. Within the context of the new communities to which they have returned, many relocated public housing residents experience increased scrutiny and intrusion that generates new kinds of stigma, exclusion, and isolation (McCormick et al., 2012). The dynamics that shape these experiences are informed in large part by institutionalized assumptions about the ‘underclass’ and the activities of organizational actors around design, service provision, intervention, and opportunities for participation and representation that, in seeking to promote integration and the establishment of new, well-functioning neighborhoods, produce new forms of exclusion for the poorest residents in them.

These dynamics are difficult to navigate, particularly given that the effort to meet the core social goals of the policy (lifting families out of poverty and revitalizing neighborhoods) takes place within the context of a market strategy, requiring the ability to attract and retain higher-income residents to these communities and to turn a profit. The analysis above, however, suggests several possible dimensions of action that might begin to address these dynamics of exclusion. One such action concerns design, the allocation of public space, and the orientation of developers and potential residents toward the kind of community being built and the nature of living in urban, mixed-income communities.

Despite the invocation of New Urbanist principles, the emerging communities are in some ways not very urban. Rather than integrated, mixed-use communities, the sites are essentially residential. Civic space is limited in favor of private spaces, commercial development has for the most part been left to later phases, and most park space is either located on the periphery of these developments or associated with condominium governance, raising issues of access. But more than simply a question of allocation or integration of public space, promoting integration may require cultivating a different orientation toward the city among residents of these communities—or seeking to attract residents who hold this orientation—in which there is both a greater tolerance in general and a willingness to embrace in particular the notion of city life as a “normative ideal,” as Young (1999, p. 236) puts it. This involves finding pleasure in diversity, embracing inclusion, and celebrating the public sphere and public space accessible to all (Chaskin and Joseph, 2013).

2.5 Urbanization and other poverty-related issues

Urbanization of poverty: Ravallion et al. (2007) find that the urbanization process has played a quantitatively important, and positive, role in overall poverty reduction, by providing new opportunities to rural out-migrants (some of whom escape poverty in the process) and through the second-round impact of urbanization on the living standards of those who remain in rural areas. However, urbanization did little for urban poverty reduction; thus the poor have been urbanizing even more rapidly than the population as a whole. Looking forward, the recent pace of urbanization and current forecasts for urban population growth imply that a majority of the poor will still live in rural areas for many decades to come. There are marked regional differences: Latin America has the most urbanized poverty problem, East Asia has the least (due mainly to China); there has been a “ruralization” of poverty in Eastern Europe and Central Asia; and in marked contrast to other regions, Africa’s urbanization process has not been associated with falling overall poverty.

Rana (2011) finds that as in other developing countries, urbanization in Bangladesh is a growing phenomenon, which is steady in nature but affects urban sustainability due to the lack of good governance. Although urban authorities are concerned about this issue, they often fail to address the problems due to the fact of uncontrollable and unpredictable rural to urban migration, as well as neglect of the urban poor’s sustainable living and access to basic services. The rural poverty problem has been virtually transposed to urban areas, particularly in the city of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Inadequacy of infrastructural services, basic amenities and environmental goods; environmental degradation; traffic jam and accidents; violence; and socioeconomic insecurity are the major challenges which are created through rapid urbanization. The case study of water supply in Dhaka demonstrates that a large proportion of people in the city lack access to water connections and a formal water revenue system. It also emphasizes the issue of ‘system hijacking’ in the name of ‘system loss’ by the water lords and corrupt government officials of the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority.

Asian urbanization and poverty: in the past several decades, Asian countries have experienced spectacular economic growth. However, the region’s economic growth has not benefited all urban dwellers equally. Urban poverty in Asia is declining more slowly than its rural counterpart; during 1993–2002 in East Asia–Pacific, for instance, rural poverty declined from 407 to 223 million (or from 35% to 20%), while urban poverty in this sub-region declined from 29 to 16 million (or from 6% to 2%: see Ravallion et al., 2007). In fact, poverty has been urbanizing in the Asia–Pacific region. In South Asia during 1993–2002, for example, the urban poor population increased from 107 to 125 million. Moreover, the Asia–Pacific region had an estimated 142 million urban poor in 2002 (Ravallion et al., 2007). Thus the question arises: despite its robust economic growth, why is urban poverty in Asian countries so significant and even on the increase? Three factors are salient. (i) Patterns of urban development: local, national and, increasingly, foreign profit-seeking enterprises drive city-based economic growth in Asia and the Pacific region – a process that has effectively excluded the poor. The redistributive channels through which the urban poor could benefit from such wealth creation are simply lacking in Asian cities. (ii) Poverty measurement and baselines: income required for essential goods for a family of four in cities and towns is higher than that for a similar household in a village. The added deprivation in cities is owing to inadequate income (commodity prices are higher in urban than rural locations), inadequate – and hence more expensive – housing, and lack of access to basic services. Due to their extralegal status, urban poor in many Asian countries are vulnerable to unlawful intrusions as well as natural disasters. (iii) Policies on poverty: given the predominant rural population in many Asian countries, governments have often considered poverty a rural, not an urban, problem. Accordingly, poverty alleviation policies have focused more on rural than urban populations – as evidenced in the different outcomes. As the region continues to urbanize, national governments would do well to address the above factors (Dahiya, 2012).

City size and poverty: Ferré et al. (2011) find an inverse relationship between poverty and city size using data from eight developing countries (Albania, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Kenya and Morocco). Poverty is both more widespread and deeper in very small and small towns than in large or very large cities. This basic pattern is generally robust to choice of poverty line. The paper shows, further, that for all eight countries, a majority of the urban poor live in medium, small, or very small towns. Moreover, it is shown that the greater incidence and severity of consumption poverty in smaller towns is generally compounded by similarly greater deprivation in terms of access to basic infrastructure services, such as electricity, heating gas, sewerage, and solid waste disposal.

Urban poverty and macroeconomic policies: Arimah (2010) finds that the prevalence of slums decreases with income. It then follows that, in order to reduce the incidence of slums, there is a need to improve the economic wellbeing of poor and low-income households, partly through income generating programs and policies that support livelihood strategies specifically designed to cater for those within the lowest 20 per cent of the income distribution. The introduction of specific safeguards to ensure housing for this group has a part to play. The key ingredient required for such initiatives is political will on the part of policymakers in order to avoid a situation where middle- and high-income groups benefit from such programs. Arimah also finds that the prevalence of slums is linked to the macroeconomic environment. In particular, an increase in financial depth will reduce the incidence of slums, while the external debt burden has the opposite effect. The policy imperative from the perspective of achieving the slum target of the MDGs is the need to adopt policies to ensure macroeconomic stability, especially in countries where macroeconomic policies are characterized by inconsistencies. At the same time, heavily indebted countries need to implement sound microeconomic policies in order to benefit from the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative, which is geared towards larger reductions in both total accumulated debt and debt service payments. Rapidly urbanizing countries have a higher incidence of slums. This is an indication that cities in developing countries need to plan based on the principles of sustainable urbanization. In this regard, urban planning can address the problem of slums and informal settlements through upgrading programs which entail the provision or improvement of infrastructure and basic services such as water, sanitation, garbage collection, storm drainage, street lighting, paved footpaths and streets (UN-HABITAT, 2009).

Shahbaz et al. (2010) contend that in Pakistan, poverty is mostly influenced by increasing macroeconomic shocks. Improvement in the inflow of international remittances indicates that it helps in reducing poverty. Urbanization is reducing poverty but its impact is quite negligible. In fact, this poverty reduction effect of urbanization appears more over a short span of time as compared to the longrun. The ever increasing inflationary pressure lowers the real value of nominal assets used for transactions in order to purchase basic necessities of life. Poverty trends are lowering through agriculture and trade openness, thereby showing a positive impact on the wellbeing of poor segments of the population. But economic growth in Pakistan is creating higher poverty among lower classes and benefits of this growth accrue only to rich classes. Considering the tax structure, major revenue is generated through indirect taxes; therefore, increased tax imposes a heavy burden. Moreover, increased poverty in Pakistan is also on account of the big size of government administrative expenditures.

Urban economic growth and urban poverty: Latin America has experienced a long period of sustained growth since 2003 that has positively impacted social and labor market indicators, including poverty. Sizable rates of poverty movements were observed in all five countries examined and it was found that a large proportion of householdsexperienced positive events, mainly related to the labor market; however, only a small fraction of them actually exited poverty. Demographic events and public cash transfers proved to be of little relevance; in particular, the latter did not contribute much either to intensifying poverty exits or to preventing poverty entries. Households with children experienced more (less) negative (positive) events than those without children. It appeared therefore that even when the economy behaves reasonably well at the aggregate level, high levels of labor turnover and income mobility (even of a negative nature) still prevail, mainly associated with the high level of precariousness and the undeveloped system of social protection that characterize the studied countries (Beccaria et al., 2012).

Urbanization and social stability: urban languages, hope and beliefs are brought to rural areas by public media. The standard of living in the city is often four or five times that of the countryside. The economic activities and opportunities in the city are almost infinitely varied compared to those in the countryside. Rural-urban migration is an irreversible process. When a large number of rural people settle down and their aspirations for high standards of living and rich opportunities are not satisfied, social instability might be created (Huntington, 1968, p.72-78).

Gender differences under urban poverty: Tacoli (2012) argues that urban poverty should also include a distinctive gendered dimension as it puts a disproportionate burden on those members of communities and households who are responsible for unpaid carework such as cleaning, cooking and looking after children, the sick and the elderly. At the same time, cash based urban economies mean that poor women are compelled, often from a very young age, to also engage in paid activities. In many instances this involves work in the lowest-paid formal and informal sector activities which, at times of economic crises, require increasingly long hours for the same income. Combined with cuts in the public provision of services, higher costs for food, water and transport, efforts to balance paid work and unpaid carework take a growing toll on women. A gendered perspective on urban poverty reveals the significance of non-income dimensions such as time poverty. It also highlights fundamental issues of equality and social justice by showing women’s unequal position in the urban labor market, their limited ability to secure assets independently from male relatives and their greater exposure to violence.

Urbanization and the effect of urban agriculture on poverty reduction: Zezza andTasciotti (2010) argue that on the one hand, the potential for urban agriculture to play a substantial role in urban poverty and food insecurity reduction should not be overemphasized, as its share in income and overall agricultural production is often quite limited. On the other hand, though, its role should also not be too easily dismissed, particularly in much of Africa and in all those countries in which agriculture provides a substantial share of income for the urban poor, and for those groups of households to which it constitutes an important source of livelihoods. They also find fairly consistent evidence of a positive statistical association between engagement in urban agriculture and dietary adequacy indicators.

Urban poverty and urban migration: Kundu (2007) finds out that poor households are likely to send out one or more of their adult members to other locations, possibly for creating an outside support system for livelihood. Migration to urban centers emerges as a definite instrument of improving economic wellbeing and escaping poverty, irrespective of the size of the towns. The probability of being poor is lower among the migrants compared to local population, in all size classes of urban centers. Large cities report low levels of poverty, irrespective of the migration status and nature of employment. Large cities have become less hospitable and less accommodating for the poor, reducing the absorption of economically dispossessed migrants and consequently reporting lower poverty risk when compared to smaller towns. Educational attainment emerges as the single most significant factor impacting on poverty.

Urban poverty and urban crime: Massey (1996) finds that in Philadelphia every one-point increase in the neighborhood poverty rate raises the major crime rate by 0.8 points, and in Columbus, Ohio, moving from a neighborhood where the poverty rate is under 20% to a neighborhood where it is over 40% increases the rate of violent crime more than threefold, from around 7 per thousand to about 23 per thousand.

Urbanization and youth poverty: Grant (2012) argues that youth (under 18 years old) are predicted to make up 60% of urban populations by 2030 and youth are over-represented among the urban poor. Most urban youth, particularly youth migrants, live in unplanned settlement areas, often in squalid conditions, and are vulnerable to high levels of unemployment. Grant considers the capacity of urban areas to create jobs for youth populations, distinguishing between economic sectors and between formal and informal employment. Grant concludes that the low level of formal education achievement among poor urban youth is a major constraint to remunerative urban opportunities. Education is not the only barrier to employment. Socioeconomic factors, such as the strength of local markets and an individual’s own networks, mediate the kinds of opportunities available to youth.

Poverty gap between migrants and non-migrants: Cameron (2012) uses recent data from Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, Vietnam, to examine educational expenditure and children’s grade attainment, with a focus on poor households. Cameron finds that rural-urban migrant households have fewer assets, live in worse housing conditions and in areas less well served by public schools, have fewer social connections in the area where they live, and contain adults with lower educational levels than for urban native households. Even conditional on these household characteristics, educational expenditure and grade attainment were both lower for children from migrant households than urban natives. The findings are consistent with migrant children’s education being impeded by bureaucratic obstacles such as the household registration system in Vietnam. Cameron concludes by noting that expansion of urban school systems sometimes fails to keep pace with population movements. While the barriers to education of recent migrants in these two contexts are in many ways similar to those of other poor urban households, they are among the most severely disadvantaged but do not always benefit from existing programs such as school fee waivers. Specific policies may be needed to address the multiple causes of educational deprivation for this group.

Urbanization and the impact of micro-finance (MF) on poverty reduction: BasharaandRashidb (2012) find out that urban MF is flourishing, that its impact is statistically significant and that the potential for further growth is considerable through a survey of the major cities and a sample of the minor ones. Micro-finance institution (MFI) officials see only an unlimited demand for their loans in current activities; however, if urban MFIs use their greatest asset, which is the trust given to them by their members, they can become catalysts of social as well as economic change in Bangladesh.

Impact of urban informal sector on poverty reduction: KarandMarjit (2009) find that the level of informal activity is sharply increasing in India in general although not without usual business cycles. For India, it is observed empirically that the wage and employment growth in the urban informal sectors, which typically include the non-directory manufacturing sector, is positive and considerable. The own account enterprises or the self-employed units within the informal sector also experience positive growth in prices, output and participation. Their theoretical model predicts that the wages of informal workers should increase and the informal industrial commodity expand in production if the formal import competing sector contracts due to withdrawal of trade protection. Finally, the growth in informal wages is shown to be capable of reducing the incidence of urban poverty. Although the relationship is worked out from disparate data sources, the overwhelming presence of informal workers and the glaring existence of urban poverty cannot be completely unrelated.

3. Urbanization, Urban Poverty and Terrorist Activities

Mousseau (2011) finds out that approval of Islamist terrorism is not associated with religiosity, lack of education, poverty, or income dissatisfaction based on survey respondents in 14 countries (Bangladesh, Ghana, Indonesia, Ivory Coast, Jordan, Lebanon, Mali, Nigeria, Pakistan, Senegal, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda, Uzbekistan) representing 62% of the world’s 1.5 billion Muslim population. Instead, approval of Islamist terror is linked with urban – but not rural – poverty. These results are consistent with the thesis that Islamist terrorists obtain support and recruits from the urban poor, who pursue their economic interests outside the market in politics through collective groups. The role of urban poverty is also consistent with the ‘market civilization’ thesis that Islamist terrorism is rooted in the highly insecure conditions of the larger cities of the developing world (Mousseau 2002–03). In these cities, many cannot find jobs in the market and are forced to pledge loyalty to group leaders who pursue their interests outside the market in politics with threats and acts of violence. Groups compete over state rents, so a gain for one group means a loss for another, making terrorism of members of out-groups a cost-effective strategy. The rise of militant Islam can be attributed to high rates of urbanization in many Muslim countries in recent decades, which fosters violence as rising groups seek to dislodge prior groups entrenched in power. Rising group leaders also compete over new urban followers, so they promote fears of out-groups and package in-group identities in ways that ring true with the everyday circumstances of the urban poor. Because many of the urban poor are migrants from the countryside, popular packages are those which identify with traditional rural values and distinguish enemies as those associated with urban modernity and the secular groups already in power. Imams have an incentive to preach what audiences want to hear, so a mutated in-group version of Islam – Islamism – struck a chord in several large cities around the globe at the same time. With globalization of the media, in many developing countries the West is widely (albeit wrongly) perceived as an inimical out-group associated with urban modernity. The best political strategy to limit support and recruits for Islamist terrorist groups is to enhance the economic opportunities available for the urban poor and to provide them with the needed services, such as access to health care and education, which many currently obtain from Islamist groups.

Terrorists and their leaders may be caught or killed, but as long as a community yields funds, political support, and recruits, a terrorist group can exist indefinitely. This means terrorism is a political problem as well as a criminal one, and to construct an effective political strategy for combating it we must first understand its root causes. We have also seen that the market civilization thesis, unlike prior arguments about religiosity, poor education, poverty, or income dissatisfaction, offers an account of all four salient characteristics of the global Salafi jihad. Loyal service to groups rather than states is a rational and functional response to high structural unemployment, and processes of bounded rationality can cause a de-individualization of members of out-groups, lowering the threshold at which an individual can approve of terrorism.

The collective action problem is solved because decisions for violence are made by group leaders, not followers, and leaders can directly benefit from a fight. Variance in approval of Islamist terrorism over time and space is solved with urbanization: countries with weak markets that experience high rates of urbanization are more susceptible than others to inter-group and anti-state violence as new and rising urban groups seek to establish new balances of power. It has been found that in recent decades, predominantly Muslim countries have experienced higher rates of urbanization than other countries. Finally, with globalization of the media, the West is widely perceived by insecure urban dwellers as another out-group with inimical interests, and in this way terrorism against the West is a mere continuation of local politics across borders.

Once we comprehend the in-group mindset, we can understand the ambitions of leaders of the global Salafi jihad. The whole idea of a state having the monopoly on the use of force over a geographic space makes sense only for those who regularly engage in the market, because only then is a state needed that enforces contracts equally, protects freedom to contract, and seeks to enhance the general welfare. For those dependent on groups, competition among groups is constant: winners repress losers, within and across nations. Like the Marxist and fascist massmovements in Europe a century ago – when terrorism also took root among the urban poor (Gurr 2006, p. 87) – the global Salifi jihad movement today does not recognize the legitimacy of the states it happens to be in or accept the idea that states should possess the monopoly on violence. Nor doesit approve of the Westphalian system of sovereign states: similar to the fascists, Islamists ‘insist that the entire Muslim world forms one community that should be united’ (Sadowski 2006, p. 227). It is this challenge to Westphalia that unites the nations of market civilization against them, as it is the monopoly on the use of force by states that agree on the basic norms of international law that serves as the vital backbone of the global marketplace.

While it is obvious that Islamist terrorists cannot possibly achieve their objective in overthrowing Westphalia, they fight anyway because in the clienteles’ mindset of collective loyalty, dying for the group is a matter of honor, just as it once was in Europe before the mindset changed towards individualism and defending the state (Bowman 2006). The policy implications for combating the sources of Islamist terror are direct and profound. To separate Islamist terrorists from people in which they obtain succor and recruits, states and international organizations must increase the economic opportunities available for the poor dwelling in the large cities of the Islamic world and provide them with the needed services, such as access to health care and education, that many currently obtain by pledging loyalty to militant Islamist groups. Globalization has made urban poverty a global security issue.

4. Urbanization and Rural Poverty

Impact of urbanization on rural poverty: CalìandMenon (2013),using data on Indian districts from 1983 to 1999, find that urbanization has a significant poverty-reducing effect in the surrounding rural areas. The authors use a variety of instrumental variable estimations to show that this effect is causal and in fact failure to control for causality downwardly biases the poverty-reducing effect of urbanization. On average an increase in the urban population by 200,000 determines a decrease in rural poverty in the same district of between 1.3 and 2.6 percentage points. According to these figures, urbanization was responsible for between 13 percent and 25 percent of the overall reduction in rural poverty in India over the period. This is a substantial contribution, which is higher for example than that of an important rural policy in post-independence India, i.e. land reform, which explains approximately one-tenth of the rural poverty reduction between 1958 and 1992 (Besley and Burgess 2000). Calìandand Menon find that the poverty-reducing impact of urbanization is a consequence of urban-rural economic linkages and it is not due to the relocation of the rural poor to urban areas. Distinguishing between these two effects is important. The latter entails no structural link between urbanization and rural poverty and the related variation in rural poverty is simply due to the change in residency from rural to urban areas of some of the rural poor. On the other hand, the economic linkage effects capture the impact of urbanization on the welfare of those who remain in rural areas through urban-rural linkages. This relationship indicates how good or bad urbanization is for rural poverty. Calìand and Menon find that these economic linkage effects of urbanization on rural poverty are entirely accounted for by four channels. The first is due to the increase in the demand for rural goods by an expanding urban area, which in the absence of spatially integrated food markets is disproportionately satisfied by surrounding rural areas. This channel alone explains around three-quarters of the overall effect of urbanization on rural poverty. The second mechanism works through urban-rural remittances associated with urbanization, which account for less than a fifth of the rural poverty-reducing effect of urbanization. The remaining small proportion of the effect of urbanization on rural poverty is explained by the increase in rural land/labor ratio due to rural-urban migration and to the increase in rural nonfarm employment. Expanding urban areas usually favor the diversification of economic activity away from farming in surrounding rural areas, which typically has a positive effect on income. In the case of India, this effect is small as rural nonfarm employment has an invertedU-shape relation with rural poverty. These findings suggest at least two policy messages. First, they can help to reassess the role of public investment in urban areas for poverty reduction. In fact, it is a popular tenet that investments in developing countries should be concentrated in rural areas to reduce poverty because the poor in developing countries are primarily concentrated there. However, to the extent that urbanization can have substantial poverty-reducing effects on rural areas, urban investments should become an important complement to rural investments in rural povertyreduction strategies. Second, our findings run counter to the popular myth that rural-urban migration may deplete rural areas, causing them to fall further behind. The relatively low rate of urbanization in India itself (and in China) is likely to be due at least in part to public policies that have not facilitated (and, in certain instances, have even constrained) rural-urban migration. At the very least, the above findings question the appropriateness of this bias against rural-urban migration.

Fan et al. (2005) use empirical data find thatin China, agricultural growth has contributed to poverty reduction in both rural and urban areas. But the effect on rural poverty is larger than the effect on urban poverty. On the other hand, urban growth contributes to only urban poverty reduction and its effect on rural poverty reduction is negative or statistically insignificant. The results for India show that rural growth helps to reduce rural poverty, but its effect on urban poverty reduction is statistically insignificant. On the other hand, urban growth contributes to urban poverty reduction and its contribution to rural poverty reduction is not statistically robust.

Choice of investment strategy under urbanization: Dorosh and Thurlow (2011) find that strong economic growth in urban areas has not led to rapid urbanization in Ethiopia, possibly as a result of prevailing land tenure policies. Dorosh and Thurlow examine the economic implications of accelerated urbanization using a rural–urban economy-wide model that explicitly captures internal migration and agglomeration effects. Simulation results indicate that accelerated urbanization would strengthen economic growth, improve rural welfare, and reduce the rural–urban divide. However, without supporting investments in urban areas, the welfare gains for poorer households remain small and urban inequality worsens. At the same time, while allocating more public resources to urban areas encourages economic growth, it is less likely to benefit poor households’ welfare. Indeed, even though an agriculture-oriented investment plan slows economic growth, it is more effective at improving welfare for poorer households in both rural and urban areas. Dorosh and Thurlow conclude that combining reforms to overcome the constraints to internal migration together with increased investment in rural areas (even at the cost of urban investment) produces outcomes most conducive to future economic development and structural transformation in Ethiopia.

Link between rural and urban poverty under urbanization: Mohanty (2010) finds that in the process of rapid urbanization in India, the failure of the rural poverty alleviation programs leads to migration of the poor from rural to urban areas. As the poor migrant laborers have low educational and technical skills, they end up in low-paying jobs and thus remain poor. Therefore, urban poverty cannot be dealt with separately without addressing the rural poverty of a country.

5. China’s Urbanization and Poverty

Urbanization and urban multidimensional poverty measurement: Wang and Alkire (2009) investigate China’s rural and urban poverty by using the method of multidimensional poverty measurement and the China Health and Nutrition Survey data, finding that nearly one-fifth of both urban and rural households exhibit 3 multidimensional poverty symptoms in addition to income poverty. China’s rural and urban poverty is much worse than the income poverty rate reported by the National Statistical Bureau of China. The result of decomposition by dimension shows that the contributions of sanitation, health insurance and education dominate over other dimensions. The result of decomposition by region demonstrates that the multidimensional poverty is worst in Guizhou Province. Decomposition by urban and rural areas discloses that urban multidimensional poverty is very serious in Heilongjiang Province and Guangxi Autonomous Region. Therefore, China’s poverty reduction and development guidelines should focus on identifying multidimensional poverty and the corresponding poverty reduction.

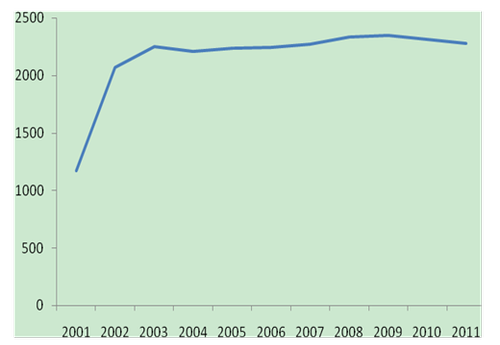

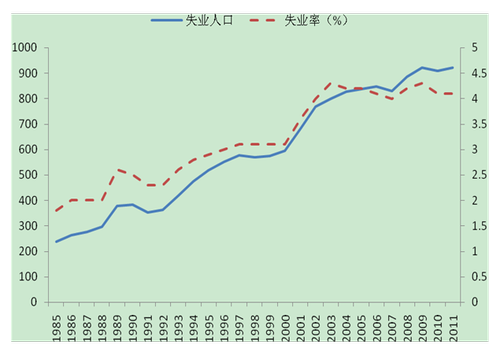

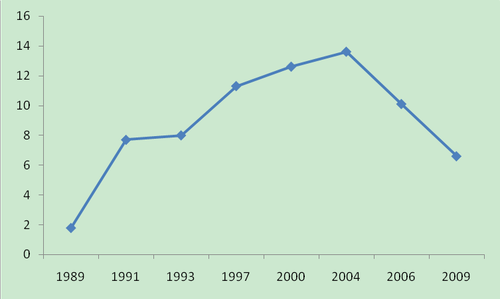

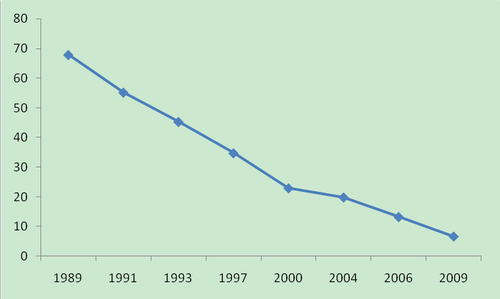

Impact of reform of the state-owned sector on urban poverty under economic growth: using Chinese Household Income Project surveys which include state subsidies and transfers in their measurement of household income, Xia et al. (2007) have shown that living standards rose across the distribution of income from 1988 to 2002. Xia et al.do find evidence that the withdrawal of subsidies during 1988–95 lowered the real income of the poorest in urban areas. However, this was subsequently outweighed by growth in other sources of income. Perhaps most surprisingly, Xia et al. find that—despite the rise of mass unemployment after 1995—absolute poverty continued to fall, irrespective of where the poverty line was set. This implies that the concern that absolute poverty has risen during urban reform is misplaced. State-funded anti-poverty programs have expanded in urban China during this period, but still had very limited coverage. They have reduced poverty according to the very narrow conception used by officials, but have had little impact on inequality or poverty more broadly defined.

Urbanization and urban villages: the presence of urban villages is a unique product of China's urbanization. Song and Zenou (2012) explore the effects of urban villages on the formal housing market and find that housing prices are lower the closer the buildings are to urban villages. Indeed, many ills may befall residents of a densely populated neighborhood (which is the case of urban villages): noise and other household pollution; congestion of public areas likestreets, sidewalks, and parks; selfishness, litter, and other social behavior fostered by crowding; and difficulties in the neighborhood beautification in built-up areas. In other words, even though apartments in the city and urban villages are physically separated, negative spillovers between these neighborhoods exist, and they are capitalized into land values. However, local municipal government could not demolish buildings because they are housing a large number of migrant workers. Therefore, local government needs to revitalize the urban villages and improve the lives of residents of urban villages.

Hao et al. (2011) investigate different dimensions of the development and redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen. Hao et al. find that the presence of massive numbers of rural migrants in cities does not result in slums or squatters due to institutional constraints. In the absence of government help, urban villages have evolved in many cities to provide adequate and affordable housing for the rural migrants. However, the urban villages are rejected by policy makers and face aggressive demolition and redevelopment programs to replace them with formal urban neighborhoods. By linking to the development practices of the city, the physical and socioeconomic evolution of urban villages is found to be a result of the natural and logical response of the indigenous village population and the rural migrants facing rapid economic development and social transition. Therefore, the demolition-redevelopment approach adopted by the government would be devastating not only for the rural migrants but also for the city’s economy, which is largely based on labor-intensive sectors. Opportunities to explore alternative responses such as upgrading or the provision of village level development guidance do exist and could be explored.

In comparison with official urban residents, housing and living conditions of migrants are relatively poor. Better-off migrants can only afford to rent a very small apartment, whilst others have to share rooms. Urban villages provide low-paid migrant workers with the first step toward affordable housing in large cities. In Shenzhen, a city growing at extraordinary speed, migrant housing conditions are no worse than those found in other cities. In comparison with what the authors have found in Chongqing and Shenyang in earlier studies, the housing conditions in urban villages in Shenzhen are in fact slightly better. Most migrants in the city live in new buildings. Although the quality of these buildings is not as good as in officially planned housing estates, they offer better accommodation than the run-down traditional houses found in other cities. Urban villages in Shenzhen provide good locations for migrant workers. Because the city developed from a small border town, many villages occupy central areas inside the new city. This locational advantage enables migrants to live close to work and cuts down on travel time and costs. Due to the shared cultural and professional background of rural migrants and the local village residents, the rental tenure is relatively safe and secure. Amenities in urban villages may not be as extensive as those in properly built new housing estates, but they are affordable (Wang et al. 2010).