2013—The 7th China-ASEAN Forum Poverty2

The above analysis shows that income distribution between 1989 and 2009 was detrimental to poverty reduction. To probe into the impact of inequality on poverty reduction, we illustrate in Table 7 the elasticity of inequality with respect to FGT poverty measurement. Table 7 shows the elasticity of the Gini coefficient with respect to the poverty headcount ratio (P0), to the PG index (P1), and to the squared PG index (P2).

Tale 7 Poverty Elasticity of Inequality

|

Year |

|

Headcount Ratio (P0) |

|

PG Index (P1) |

|

Squared PG Index(P2) |

|

1989 |

|

0.04 |

|

1.06 |

|

1.97 |

|

1991 |

|

0.07 |

|

1.19 |

|

5.42 |

|

1993 |

|

0.46 |

|

1.87 |

|

2.86 |

|

1997 |

|

0.83 |

|

2.2 |

|

3.43 |

|

2000 |

|

1.1 |

|

3 |

|

4.43 |

|

2004 |

|

1.14 |

|

4.01 |

|

3.72 |

|

2006 |

|

2.42 |

|

5.33 |

|

6.81 |

|

2009 |

|

4.24 |

|

6.58 |

|

5.69 |

Policy implications of the above breakdown show that between 1989 and 2009, when income growth was constant, if income distribution had been improved, the poverty headcount might have been reduced even further. This also tells us that in the years to come, income distribution can be an effective instrument for poverty reduction.

4. Suggestions for Urban Poverty Reduction

4.1 Build a strategic framework to reduce urban poverty.

As urbanization continues, urban poverty will become a significant problem that we cannot afford to ignore or avoid. The government should pay great attention to urban poverty and design a comprehensive strategic framework which includes an improved social security network for urban households and specific policy measures that monitor and target poor urban populations. A combination of development-oriented and assistance-based poverty reduction in rural areas can be applied in urban areas. Considering how difficult it is to tackle poverty, the Chinese government should enact legislation targeting poverty reduction.

4.2 Migrant populations cannot be ignored.

Migration poverty has become an increasingly important form of urban poverty [6]. Poor rural migrant workers are not included in the empirical data of this paper, but they are increasing in number, reaching 158.53 million in 2011. Many of them will inevitably become the lower middle class under hukou restrictions and suffer inequitable treatment. Relaxing hukou restrictions or disconnecting the hukou from urban welfare systems to coordinate urban and rural development and expand coverage of an urban social security net will be effective policy tools to alleviate poverty of rural migrant workers.

4.3 Establish and improve a pro-employment policy system and expand employment in informal sectors.

Employment is the most direct and most fundamental way to lift poor urban residents out of poverty. The government should encourage employment through multiple means, such as expanding the business area and scope of employment, strengthening the capacity of human capital and widening up the labor market. Since the international financial crisis of 2008, the role of SMEs and labor-intensive enterprises as major employers and especially informal employers has proven to be very constructive. Therefore, they deserve strong national fiscal and financial support.

4.4 Improving income distribution should be regarded as a vital way to reduce poverty and inequality.

The income gap between China’s urban residents is reflected in the Gini coefficient of urban residents, which is now alarmingly above the international line of 0.4%. In 2010, according to urban household income distribution across five equal groups, the highest income group earned 5.4 times more than the lowest income group. In line with the goal to “increase income of low income households, expand middle income groups, adjust income of high income households and crack down on illegal sources of income”, the government should improve the structure and model of distribution, deepen institutional reform of income distribution, ease conflicts triggered by the widening income gap and eventually alleviate urban poverty.

References

1. Du Yang (2007), Urban Poverty in China: Trend, Policy and New Issues [R], China Development Research Foundation Report, Issue 34.

2. Hong Dayong (2003), On Urban Poverty Reduction in China Since Reform and Opening-up, Journal of Renmin University of China, 1: 9-16.

3. Jiang Guihuang, Song Yingchang (2011), Urban Poverty and Anti-poverty Policy in China [J], Urban Modern Research, 10: 8-10.

4. Jonathan Haughton, Shahidur R. Khandker (2009), Handbook on Poverty and Inequality [M], Washington DC, The World Bank. 67-80.

5. Planning and Finance Department of Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, Report of PRC on The Social Services Development in 2011 [EB/OL], 21 June 2012.

6. Wang Xiaolin (2012), The Measurement of Poverty: Theories and Methods [M], Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press, 2012:91.

Chapter 3: China's Urban Poverty: A Multidimensional Perspective

ZHOU Liang, WANG Xiaolin

1. Introduction

In his 1901 book "Poverty: A study of Town Life", Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree estimated poverty in the city of York, United Kingdom according to the currency budget for the "shopping basket" "necessary to maintain physical well being, with the minimum weekly food budget for a family of six of 15 shillings. Adding an allowance for shelter, clothing, fuel, and sundries, he arrived at a poverty line of 26 shillings for a family of six, which implied a poverty rate of almost 10% in York at the time. This is the first ever accurate measurement of urban poverty, putting forward a method for measuring a poverty line (Wang Xiaolin, 2012).

Over the past century, human society has mainly measured poverty based on income. Economists emphasized the importance of income in meeting people's basic needs to achieve poverty reduction. Over the past two decades, people have constantly expanded their perspectives on the understanding of poverty, aimed at finding the true causes of poverty and appropriate pro-poor policies. Amartya Sen's poverty theory has led people to realize that poverty cannot be simply measured by an absolute poverty line based on income and consumption. Instead, we must conduct a comprehensive analysis on poverty from a multidimensional perspective, covering basic social services, nutrition, sources of water, health, education and information.(Minujin and Delamonica, 2005; Roelen and Gassmann, 2008). Urban poverty thus should also be studied from a multidimensional perspective.

Urbanization is the historical process of the gradual transformation from a traditional agriculture-based rural society to an industry and service-oriented modern urban society. Urbanization promotes the development of urban industry and services and thus achieves economic growth, promotes employment and reduces poverty. Recent studies, however, have found that many countries have witnessed urbanization of poverty or the transfer of poverty in the process of urbanization. Meanwhile, governments of developing countries are challenged by urban slums. The urbanization of poverty is related to the employment, education, health, environment and housing conditions of the poor. The government, therefore, should develop appropriate policies from a multidimensional perspective while addressing poverty in the process of urbanization.

The Chinese government put forward the macro strategic goal of building a middle income society by 2020. At present, China's urbanization rate is above 50% and China has entered into a stage of rapid urbanization. With the transfer of a large number of people from the countryside to the city, the poor can been divided into three groups: poor urban registered residents, poor urban migrants, and the poor left behind in the countryside. The analysis of urban poverty by division of household registration (hukou) and the measurement of poverty by income cannot provide an adequate policy basis for coping with urban poverty in rapid urbanization. Taking these factors into consideration, this report analyzes China’s urban poverty from a multidimensional perspective, aiming at providing a more comprehensive basis for building a pro-poor strategy and policy system under the development strategy of urban-rural integration.

2. Theoretical Framework and Method

2.1 Theoretical Framework

The theoretical basis for this paper’s analysis of multidimensional poverty of urban residents in China is the Capability Approach proposed and developed by Amartya Sen in 1979.

Amartya Sen abandoned the concept of "income", "consumer spending" or "utility" as in traditional economics and welfare economics, and turned to measure human well-being and the level of social development based on individual "capability". Capability is when "people can have the capability do their own thing and live a life of their own" (Alkire S. etc., 2010). The capability approach is considered to be a framework to assess and balance the level of individual well-being with social institutional provisions (Robeyns, 2003). Its main idea is that society should work to improve the extent of freedom people have to promote or achieve functions they value. In other words, a person should have the freedom to do or be whatever he or she may value doing or being. This method was later used in the analysis of poverty problem. Sen put forward the concept of capacity poverty and argued that the cause of poverty is lack of capacity.

2.2 Analysis Method

In practice, Alkire and Foster proposed an approach to build multidimensional poverty indices, i.e. the Alkire-Foster (AF) approach. This is a relatively mature approach among a variety of multidimensional poverty measurement methods, which is flexible and widely used in domestic and foreign multidimensional poverty studies. Since 2010, UNDP's Human Development Report announces the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) of more than 100 countries calculated with this approach every year.

The basic steps of the AF approach are as follows: First, determine the dimensions of poverty, such as education, health and living standards; second, determine indicators of each dimension; third, set the deprivation cut-offs. For example, if an adult has not completed five years of education, he lives in education poverty; Fourth, determine the multidimensional poverty threshold. For example, among five dimensions, if three dimensions show deprivation, there is multidimensional poverty. Fifth, calculate the headcount ratio (H) and average deprivation share among the poor (A), and the adjusted headcount ratio-Multidimensional Poverty Index (M0) can be calculated after the adjustment of H by A. Sixth, carry out test.

The selection of dimensions is very important in the analysis of multidimensional poverty. For people who live in the city, employment is the most important dimension to generate income and maintain a decent living. Education and health are important dimensions of social services as human resources. Housing and environment are important aspects to reflect the quality of life. The five dimensions for the analysis in this paper, therefore, respectively reflect the capacity of urban residents in five areas, namely employment, education, health, housing and environment (Table 1).

Table 1 Setting of dimensions and indicators

|

Dimensions |

Indicator |

|

1. Employment |

Employment |

|

2. Education |

Education |

|

3. Health |

Drinking water |

|

Sanitary facilities |

|

|

Medical insurance |

|

|

4. Housing |

Housing size |

|

Consumer durables |

|

|

5. Environment |

Lighting energy |

|

Cooking energy |

|

|

Environmental hygiene |

First, the employment dimension reflects the situation of deprivation of urban residents in the labor market. The right and obligation to work is provided by the constitution. Unemployment of the working age population is a serious deprivation of this right. In the "China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS)"questionnaire , "employment" covers 12 kinds of occupations and seven major types of employment. A rural unemployment problem does not exist by default. For urban residents, however, unemployment means loss of income. Employment status is usually directly related to family poverty and is an important dimension to measure urban multidimensional poverty.

Second, the education dimension reflects the education of urban residents. For school-age children (6-15 years old), it is a fundamental right to receive education, so the dropout rate determines deprivation. For people over 15 years old, this paper takes primary school education as the standard to determine whether their learning capability has experienced deprivation. According to the revised "Regulations for the Work of Eliminating Illiteracy" promulgated by the State Council in 1993, the rating standard of literacy for workers of enterprises and institutions and urban residents is to be able to identify two thousand Chinese characters, understand simple popular newspapers and articles, remember simple accounts and do simple practical writing, which is slightly higher than the rating standard of literacy for farmers. The "basic illiteracy unit" standard is: "..... The literacy rate, not including those who lost the ability to learn, reaches 98% or above in the town"; "basic illiteracy units should popularize primary education". Considering the above criteria and the actual operability, this paper takes five years of education as the criterion to determine whether the learning capability of interviewees over 15 has been deprived.

Third, the health dimension reflects urban residents’ access to clean water and sanitary facilities as well as their capability for health care.

Access to improved drinking water and sanitation is one of the criteria to measure the level of urban living standards and are important indicators of the Millennium Development Goals. Access to clean drinking water and sanitation directly affect the health of family members. Literature of the United Nations has relevant standards for "access to improved access water and cleaning facilities", though it is difficult to implement the regulation and measure the situation. In accordance with common standards, coupled with stringent requirements, this paper sets its own standard for the deprivation of drinking water and sanitation. See Table 2 for details.

Medical insurance is an important indicator reflecting the dimension of citizens’ health security. In 1998, the State Council issued the Decision on the Establishment of Basic Medical Insurance System for Urban Workers and China began to set up such a system nationwide. Through continuous reforms, the coverage of basic medical insurance continues to expand. All urban employers are required to purchase basic medical insurance for their employees. The governments of provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities decide whether individual urban entities and their employees must participate in the basic medical insurance system. Other types of insurance, such as commercial insurance, are supplements to the basic medical insurance. The "health insurance" indicator reflects whether urban residents’ medical security can be considered as deprived.

Table 2 Indicator and weight setting

|

Dimensions |

Indicators |

Indicators setting |

Weight |

|

1.Employment |

Employment |

Exclude the following situations: under 18 years of age, women over 55, unemployed-men over 60, retirees and unemployed students, the unemployed: 1 |

1/5 |

|

2.Education |

Education |

6-15 year-old out-of-school children: 1 People above 15 who no longer go to school and have not completed five years of schooling (regarded as not completed primary education): 1 |

1/5 |

|

3.Health |

Drinking water |

The family obtaining drinking water "other" ways or from "open wells": 1 |

1/15 |

|

Sanitation facilities |

The family not using indoor flushing toilets: 1 |

1/15 |

|

|

Medical insurance |

Without medical insurance: 1 |

1/15 |

|

|

4.Residence |

Housing size |

Household per capita housing area is less than 13 sq.m. (including 13 sq.m.): 1 |

1/10 |

|

Durable goods |

The family does not have one of the following assets: TV set, washing machine, refrigerator, computer, telephone, mobile phone, VCD, DVD and satellite antenna: 1 |

1/10 |

|

|

5.Environment |

Lighting energy |

The family uses kerosene lamps, oil lamps or candles for lighting: 1 |

1/15 |

|

Cooking energy |

The family uses coal, kerosene, firewood, matches, grass or charcoal for cooking: 1 |

1/15 |

|

|

Environmental hygiene |

Human waste is near the household: 1 |

1/15 |

Fourth, living conditions reflect the basic right to shelter of urban residents. Due to different standards for urban residents, this paper does not use this indicator to measure the quality of housing as prescribed in the International Multidimensional Poverty Index, instead using per capita living space. Overcrowded or cramped housing space indicates deprivation. At present, China's urban per capita housing area has reached 30 square meters or more, but there are still a large number of families with housing problems (Li Keqiang, 2011). Standards for families with housing difficulties are vary among regions. For example, the targets of low-rent housing are mainly determined by urban governments according to a certain proportion of the household disposable income per capita and housing area per capita as announced by the local statistics department, combined with the level of urban economic development and housing prices. Using the CHNS areas, , we take per capita housing area of 13 square meters as the standard for housing difficulty. Another index reflecting living conditions is the ownership of consumer durables.

Fifth, the environmental dimension reflects the basic living conditions of urban residents. The indicators include lighting, cooking energy, as well as the surrounding living environment. According to the WHO and UNDP joint report (2009), electricity and modern fuels are the main indicators to measure a family’s degree of access to modern energy, referring to "electricity, liquid fuel or gas fuel for cooking". This definition excludes the use of firewood, charcoal, animal dung and other traditional biofuels, or the use of cinder, lignite, etc. The use of these non-modern fuels releases harmful smoke, especially dangerous to women and children's health. This paper mainly discusses two indicators, namely lighting energy and cooking energy. This dimension also reflects the surrounding sanitary conditions. These indicators reflect the overall living environment of urban residents.

Five dimensions are given equal weights in this paper and each of the indicators for each dimension are given equal weights as well. See Table 2 for the specific definitions and weight setting of the indicators.

3. Data Source

Data in this paper are from the China National Nutrition and Health Survey (CHNS) (2009) collected by the joint investigation conducted by the University of North Carolina Population Center and the Institute for Nutrition and Food Safety of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. This paper does not consider permanent residence as the criteria for classification, and defines urban residents as the "residents living in the city". This way, it covers not only registered urban residents, but also the migrants in the city who are registered as rural.

Data in this paper mainly come from five sheets within the CHNS database (2009), including the sheet of personal income, household income, assets, employment and education. The interviewees are urban residents, including those who are registered as rural but work in the city. Excluding the observed samples with incomplete data, we finally obtained a total of 3744 samples, including 1793 from men and 1951 from women.

4. Main Conclusions

4.1 The situation of China's urban multidimensional poverty is serious

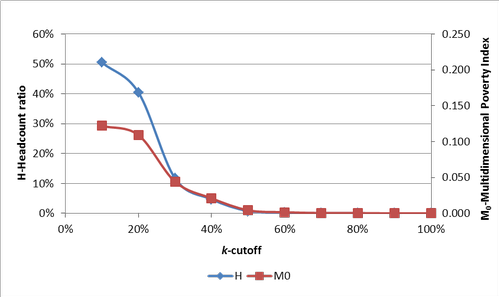

In our analysis, we assume k = 30% as a multidimensional poverty threshold, that is: when the deprivation level of a person reaches 30%, this person lives in multidimensional poverty, therefore 11.73% of urban residents live in multidimensional poverty (headcount ratio, H). The average level of deprivation is 37.69% (average deprivation share among poor, A), that is on average, the residents in multidimensional poverty of these cities experience deprivation by about 38%. Taking into account the average level of deprivation, the adjusted headcount ratio- Multidimensional Poverty Index (M0) is 0.044.

Table 3 H, A and M0 under different thresholds

|

|

H |

A |

M0 |

|

10% |

50.45% |

24.18% |

0.122 |

|

20% |

40.44% |

26.97% |

0.109 |

|

30% |

11.73% |

37.69% |

0.044 |

|

40% |

4.73% |

44.43% |

0.021 |

|

50% |

0.77% |

55.63% |

0.004 |

|

60% |

0.24% |

66.67% |

0.002 |

|

70% |

0.05% |

83.33% |

0.000 |

|

80% |

0.05% |

83.33% |

0.000 |

|

90% |

0.00% |

|

0.000 |

|

100% |

0.00% |

|

0.000 |

Figure 1 Headcount ratio (H) and Multidimensional Poverty Index (M0)

4.2 The employment dimension has the greatest impact on urban multidimensional poverty, followed by the education dimension

We can see from Table 4 that the employment dimension contributes most to multidimensional poverty, up to 30.10%. It means that the lack of employment is the main cause of multidimensional poverty. Unemployment in the city often directly indicates a status of multidimensional poverty. Access to stable and decent jobs will help greatly eliminate the phenomenon of urban multidimensional poverty. Among urban residents in multidimensional poverty, 6.65% are deprived of employment.

Secondly, the education dimension contributes 27.80% to multidimensional poverty. That is to say, 28% of China’s urban residents live in multidimensional poverty due to the lack of basic education. 6.14% of urban residents in multidimensional poverty have been seriously deprived of education. Among them, only two are out-of-school children, accounting for a mere 0.86%; about half are over 50 and half are working age. In urban life, a low level of education is often accompanied by a low level of employment and poor living conditions..

Table 4 Percentage contribution of indicators and dimensions (k=30%)

|

Dimensions |

Indexes |

Indicators' contribution |

Dimensional contribution |

Censored Headcount |

|

1.Employment |

Employment |

30.10% |

30.10% |

6.65% |

|

2.Education |

Education |

27.80% |

27.80% |

6.14% |

|

3.Health |

Drinking water |

0.77% |

16.52% |

0.51% |

|

Sanitation facilities |

10.84% |

7.18% |

||

|

Medical insurance |

4.92% |

3.26% |

||

|

4.Residence |

Housing size |

9.31% |

10.15% |

4.11% |

|

Consumer durables |

0.85% |

0.37% |

||

|

5.Environment |

Lighting energy |

0.20% |

15.43% |

0.13% |

|

Cooking energy |

7.70% |

5.10% |

||

|

Environmental hygiene |

7.53% |

4.99% |

Among the health dimensions, sanitation facilities and medical insurance have a significant impact. This paper uses relatively stringent criteria for sanitation facilities thus this index has a high contribution rate. Sanitation facilities are the facilities necessary to ensure the household and community environment is clean, tidy and safe. In order to avoid the emergence of urban slums, it is very important to focus on sanitation. The improvement of sanitation facilities will bring a new look to the community and thus effectively reduce urban multidimensional poverty.

Among other indicators, the following indicators contribute significantly to urban multidimensional poverty: housing size, cooking energy and environmental hygiene.

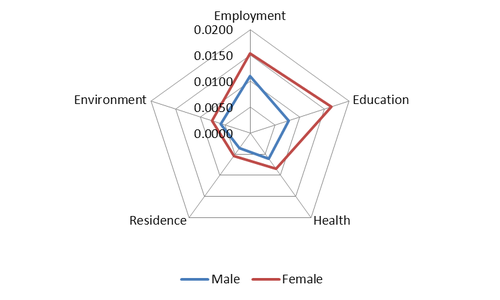

4.3 More women have fallen into multidimensional poverty

Based on the data in Table 5, the women’s multidimensional headcount ratio (H) and Multidimensional Poverty Index (M0) are both higher than that of men, but the average deprivation share (A) is almost the same. It means that among urban residents, women are more vulnerable than men to multidimensional poverty and women’s multidimensional poverty situation is more severe.

As for differences in specific dimensions, women’s circumstances are more serious than that of men, especially in their education, employment and health dimensions. The number of women among those in multidimensional poverty whose education dimension shows deprivation is twice that of men.

Table 5 Gender differences in multidimensional poverty(k=30%)

|

|

Dimensions |

Indicators |

Male |

Female |

|

Total |

|

H*** |

9.09% |

14.15% |

|

A |

37.79% |

37.63% |

||

|

M0*** |

0.034 |

0.053 |

||

|

Decomposition of M0 in each dimension |

1.Employment |

Employment |

0.011 |

0.015 |

|

2.Education |

Education |

0.008 |

0.016 |

|

|

3.Health |

Drinking water |

0.0003 |

0.0004 |

|

|

Sanitation facilities |

0.004 |

0.006 |

||

|

Medical insurance |

0.002 |

0.002 |

||

|

4.Residence |

Housing size |

0.003 |

0.005 |

|

|

Consumer durables |

0.0002 |

0.001 |

||

|

5.Environment |

Lighting energy |

0.0001 |

0.0001 |

|

|

Cooking energy |

0.003 |

0.004 |

||

|

Environmental hygiene |

0.003 |

0.004 |

***, **, * represent significant difference at significance level of 1%, 5% and 10% respectively

Figure 2 Gender differences in the dimensions(k=30%)

4.4 The multidimensional poverty of city migrants registered as permanent rural residents needs urgent attention

The scope of study of this paper includes all people in cities registered as either urban or rural permanent residents. As the "floating population" begins the process of urbanization, what is the situation of the migrants in the city? Do they experience more serious multidimensional poverty? This paper specifically compares and analyzes the differences in multidimensional poverty among various groups. According to the above criteria, of the 3744 samples, 1164 are registered as rural residents.

Table 6 Differences in registered households of people in multidimensional poverty(k=30%)

|

|

Dimensions |

Indicators |

People not registered as rural residents |

Migrants registered as rural residents in the city |

|

Total |

|

H*** |

7.13% |

21.91% |

|

A** |

36.72% |

38.39% |

||

|

M0*** |

0.026 |

0.084 |

||

|

Decomposition of M0 in each dimension |

1.Employment |

Employment*** |

0.009 |

0.022 |

|

2.Education |

Education *** |

0.007 |

0.024 |

|

|

3.Health |

Drinking water*** |

0.0001 |

0.0009 |

|

|

Sanitation facilities*** |

0.002 |

0.012 |

||

|

Medical insurance |

0.002 |

0.002 |

||

|

4.Residence |

Housing size* |

0.004 |

0.005 |

|

|

Consumer durables*** |

0.0001 |

0.001 |

||

|

5.Environment |

Lighting energy |

0.0001 |

0.0001 |

|

|

Cooking energy*** |

0.002 |

0.007 |

||

|

Environmental hygiene *** |

0.001 |

0.009 |

***, **, * represent significant difference at significance level of 1%, 5% and 10% respectively

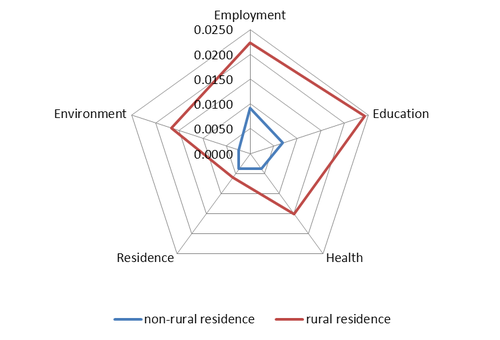

According to Table 6, the rural household population incidence of multidimensional poverty (H), average deprivation share (A) and the overall Multidimensional Poverty Index (M0) are significantly high. By decomposition, we can further analyze the difference between the two groups of people: except for those of medical insurance and lighting energy, there are significant differences in all other indices.

Meanwhile, we also found in our analysis that the most of the rural household population relies on the new type of rural cooperative medical care for medical insurance, which is mainly for farmers, focusing on treatment of major illness. Further analysis needs to be conducted on whether the new rural cooperative medical system can meet the needs of migrants in the city.

Figure 3 Household differences in each dimension(k=30%)

We can see from Figure 3 that the dimensions of employment and education of the two populations are quite different. The situation of migrants registered as rural residents in the city is concerning. They are subject to a lower level of education, more severe unemployment situation, inconvenient access to clean water and sanitation facilities as well as worse living conditions and environment.

5. Policy Recommendations

Based on the above analysis of China's urban multidimensional poverty index system, we can come to comprehend the level, causes and characteristics of urban multidimensional poverty in China.

First, urban multidimensional poverty in China is serious. According to the rates of contribution of multidimensional poverty dimensions in this paper, the priority order for addressing urban multidimensional poverty should be: employment - education - health - environment - living.

Among these dimensions, the employment dimension has the greatest impact on urban multidimensional poverty. "Any plan for economic development and poverty eradication will inevitably include analysis of labor market conditions and their improvement " (Lugo, 2010). In the process of urbanization, ensuring employment for the labor force is an important part of multidimensional poverty elimination. Education and health dimensions also have a great impact on urban multidimensional poverty. The standards in China’s Poverty Alleviation and Development Program in the new era include "no worries about food and clothing, protection of rights to compulsory education, and basic medical care and housing." Although this is the standard for poverty alleviation in rural areas, the basic education, health care and housing dimensions in urban areas should also be protected.

Second, there is a gender difference in urban multidimensional poverty, particularly in education and employment. Through specific and targeted measures, such as training to improve their employment skills, we can improve women's circumstances in these two dimensions. In recent years, the male-female wage gap in China has expanded. This indicates that we should urgently strengthen women’s education and training to enhance their ability for development. Otherwise, with the upgrade of the national industrial structure, more and more women will work in low-skill service sector jobs and the gender differences increase further.

Third, in the process of urbanization, the situation of multidimensional poverty of the rural household population is more serious. The living standard of the rural household population in the city is lower than that of urban residents and their living situation is definitely concerning. Addressing this problem will help promote social harmony and stability and contribute to the advance of urbanization to improve the multi-dimensional poverty situation of this group. The priority order to be considered is education - employment - environment - health – living. Reform of the household registration system and the equalization of basic public services is an important starting point to reduce the multidimensional poverty of migrants in the city.

Fourth, the disadvantaged among the urban residents need more attention. Women and migrants in the city are disadvantaged groups in society. By comparing the dimensions, we can discover the main causes of poverty of these groups, then provide targeted services and link government policies to the specific needs of the residents. Services for target groups can also improve the efficient use of limited public resources and thus better alleviate urban multidimensional poverty.

References

1. Alkire, S., Foster, J.E.(2007), Counting and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative, OPHI Working Paper 7.

2. Alkire, S., Foster, J.E.(2009), Counting and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative, OPHI Working Paper 32.

3. Index on Employment, Alkire S., etc, translated by Liu Minquan and Han Hua (2010), "Missing Dimension of Poverty", Beijing: Science Press.

4. Minujin A. and Delamonica E.(2005) , Incidence, Depth and Severity of Children in Poverty, UNICEF Division of Policy and Planning Working paper.

5. Robeyns I. (2003), Sen’s Capability Approach and Gender Inequality: Selecting Relevant Capabilities, Feminist Economics, 9(2/3):61-92.

6. Roelen K. and Gassman F.(2008), Measuring Child Poverty and Well-Being: a Literature Review, Maastricht, The Netherlands, Maastricht Graduate School of Governance Working Paper, Series No. WP001.

7. Several Opinions of the State Council on Solving Housing Difficulties of Urban Low-income Families, State Council, 2007

8. Wang Xiaolin (2012), "Poverty Measurement: Theory and Methods", Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

9. Wang Xiaolin, Alkire, S. (2009): "China Multidimensional Poverty Measurement: Estimation and Policy Implications", "China's Rural Economy", No.12

10. WHO, UNDP (2009), The Energy Access Situation in Developing Countries, A Review Focusing on the Least Developed Countries and Aub-Saharan Africa.

11. WHO, Unicef (2013), Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water 2013 update.

Chapter 4: Social Exclusion of the migrant Population in China

WANG Xiaolin, ZHANG Lu

1. Introduction

China is experiencing rapid urban growth, with 46% of the population living in urban areas in 2010, up from 29% in 1995. 260 million migrant workers as the main body of the migrant population are both a new force in urban construction and a main source of new labor in urban areas. The report of the Eighteenth National Congress of the Communist Party of China set forth the goal of completing the building of a moderately prosperous society in all respects by 2020. Furthermore, the new urbanization strategy requires reversal of land urbanization faster than population urbanization. This requires special attention to the migrant population.

Large scale rural-to-urban migration under the current system of household registration (hukou) means that people cannot equally access basic public services in the receiving urban area. The 12th Five Year Plan recognizes this squarely and seeks to promote the equalization of basic public services and integrated rural and urban development as key measures for social inclusion. A recent report titled “China 2030” by the World Bank and the DRC also highlighted the major source of anxiety as the peculiar pattern of migration to China’s urban areas. There are complex gender issues intertwined with a strange demographic transition that involves very low fertility, long life expectancy and spilt families as a result of migration. Chinese authorities recognize this and aim to transform the past growth pattern into a more inclusive one.

While large scale rural-to-urban migration is a defining factor of China’s urbanization process, under the current system of household registration (hukou) an individual only has rights to housing, education, food and social security in the district in which he/she is registered. China has begun taking steps to relax the hukou system and expand the coverage of services to rural migrants. Reform of the registration system is considered necessary to (i) expand access to services to migrant populations who otherwise will remain vulnerable; as well as (ii) to increase labor mobility. In addition, reform will be essential to reduce mounting social tensions in urban areas and to address key issues of social exclusion for those left behind in rural areas.

The hukou system poses specific challenges to households’ “migration strategies.” These are underpinned by cultural values and norms about the roles of men and women. The inability to migrate as a household means that critical decisions have to be made about who migrates and who remains behind (and what the obligations to family and social networks are for those who migrate and for those who stay behind). The proportion of female migrants is increasing overall. However, women are still believed to make up a large proportion of those left behind (together with children and the elderly). Typically, Chinese female migrants have tended to be younger (single) with the transition to marriage/child bearing considered particularly challenging. Lack of access to services (particularly childcare) and informal social support networks is likely to result in a return to sending areas for women migrants (at least temporarily). For women “left behind” in (or returning to) rural areas to ensure the care of children and elderly relatives, limited access to off-farm employment and basic services, the loss of male household labor and the heavy burden of care have a significant impact on their well-being.

Research on migration and social exclusion in China has tended to focus on the “integration” of migrant workers in urban/receiving areas. Since the mid-2000s a growing body of literature has sought to understand the impact of migration on the well-being of those “left behind” in rural areas. This paper focuses on the following key areas:

(1) The basic gender trends of China’s migrant populations. Interaction between gender roles and how women and men participate in migration.

(2) The effects of gender roles/social norms on women’s and men’s experiences of migration. What are the main driving forces of the migration? How do gender roles exert their influence across sending and receiving areas? What is the impact of the disruption of gender roles for “left-behind” men and women? How does marriage impact on migration?

(3) The effects of migration on gender. Changes in agency that may result from being “left behind”. Changes in bargaining power (for women who have previously migrated). Impact on decision-making within the household for left-behind women. The roles and influence of family structure and in-laws. Impact on social standing within the community (village decision-making) for those “left behind”.

(4) The social exclusion of the migrant populations. Can the migrant workers access basic public services?

(5) Evolution of migration policy in China.

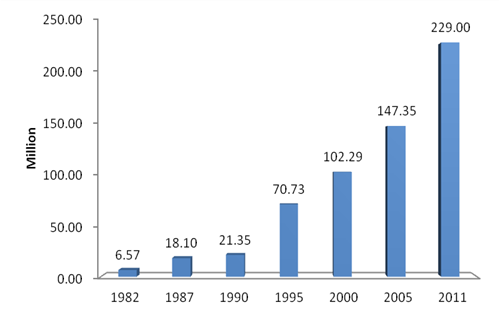

2. Basic Gender Trend of China's Migrant populations

Rapid industrialization and urbanization have brought an active growth in migration, one of the remarkable social phenomena in China (see Chart 1). Since the early 1980s, the numbers of migrants have begun rapidly expanding and this trend has continued into the 21st century. Based on the Communiqué of the 1% Demographic Sampling Survey 2005, as of midnight on November 1, 2005, there were 147.35 million rural-urban migrants nationwide, accounting for over 11% of the national total (Duan Chengrong, Zhangfei et al., 2009). According to the Dynamic Monitoring and Survey of the Floating Population 2011, at midnight on October 1, 2011, there were 229 million migrant people, taking up 17% of the national total. Rural-registered migrants accounted for 80% of the total and the remaining 20% were urban-to-urban migrants.

Chart 1 China's Migrant Populations

Source: Data for 1982, 1990 and 2000 from National Census; data for 1987 and 2005 from 1% Demographic Sampling Surveys; and data for 2011 from the Dynamic Monitoring and Survey of the Floating Population 2011. Charted by the author.

2.1 More balanced gender mix among migrants

According to Duan Chengrong and Zhangfei (2009), in the 1990s, there were evidently more male migrants than female ones. But in recent years, the gender mix of migrant populations has become equalized with women taking up a greater proportion. In 1990, the sex ratio of migrants was as high as 125. And the 1% Demographic Sampling Survey 2005 showed that the sex ratio had been reduced from 107.25 in 2000 to 100.47 in 2005, evidencing that women accounted for half of all migrants nationwide. Among the 229 million migrants in 2011, there were 115 million male ones and 114 million female ones, and the sex ratio was 100.88. The gender mix of migrants from ethnic minorities has become more and more balanced as well. In 2011, men and women accounted for 50.9% and 49.1% of all ethnic minority migrants, and the sex ratio was 103.8 (Dept. of Services and Management of Migrant Population, NPFPC, 2012). The traditional view that "male migrants are more than female ones" should be changed.

2.2 Younger female migrants

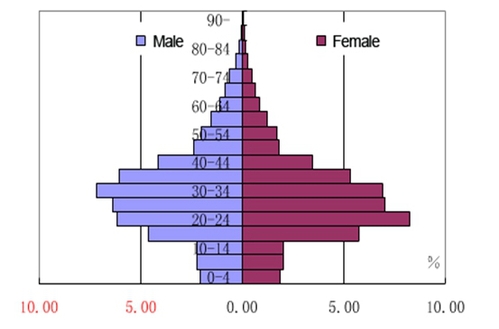

Age is a major influence upon people's socioeconomic activities. Those migrating from rural areas to cities are mainly working-age populations. According to Li Bohua et al. (2010), those at prime working age make up a larger proportion of the migrant populations. Migrants are aged 27.3 on average, and those in the age bracket of 22-24 make up 2/3 of the total. It is worth noting that there is a high proportion of children under age 14, accounting for 20.8% of the total. Based on their analysis of migrants' age structure in 2005, Duan Chengrong, Zhangfei et al. (2009) reported that the average age of female migrants and male ones was 30.04 and 31.45. Moreover, in the age brackets of 15-19, 20-24 and 25-29, female migrants far outnumbered male ones and the sex ratio was 80.55, 75.10 and 90.35 respectively (Chart 2).

Chart 2 Gender/Age Pyramid of Chinese Migrant Population

Source: 1% Demographic Sampling Survey 2005, quoted from Duan Chengrong, Zhangfei et al. (2009).

2.3 Family migration is now the main Trend

According to the Survey on Migrant Populations 2011, there were about 2.5 persons per household in migrant receiving areas. Among all migrant populations, 19.8% were children aged 0-14 years, 79.7% working-age migrants aged 15-59 years, and over 0.5% people aged 60/60+ years. Among married migrants aged 16-59 years, 85.2% of people migrated with their spouse. Among children of migrant workers, 62.3% migrated with their parents, while 37.7% were left behind (Dept. of Services and Management of Migrant Population, NPFPC, 2012).

2.4 Migrant Populations mainly concentrate in large- and medium-sized cities in eastern china

Among inflows of inter-provincial migrants, 24.23% went to Guangdong, 23.60% Zhejiang, 12.68% Shanghai, 10.46% Beijing, 8.87% Jiangsu and 6.97% Fujian. The 6 provinces received about 86.81% of inter-provincial migrants of China.

Among outflows of inter-provincial migrants, 18.40% were from Anhui, 10.81% Henan, 9.94% Hunan, 8.66% Jiangxi and 7.70% Guizhou. The 6 provinces accounted for 72.45% of out-migration.

3. Interaction between gender roles and how women and men participate in migration

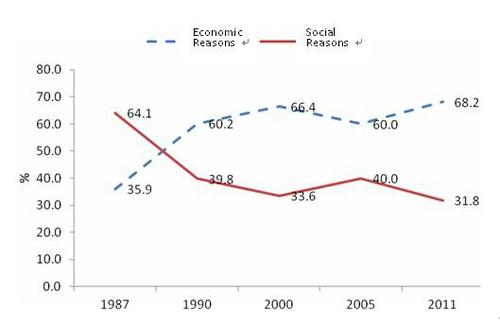

3.1 Women migrate more for economic reasons than for social ones

Data from the 1% Demographic Sampling Survey 1987 show that migration for business or work accounted for 26.58%, and marriage, 21.04%, these two reasons almost running in parallel. Over that period, migration due to job transfer, job assignment/offer, doing business/off-farm work and other economic reasons took up for 32.97%. Migration as a result of marriage, staying with friends and relatives and accompanying migrant family members accounted for more than half of the total migration driven by social reasons (54.89%). In other words, in the 1980s, socially-driven migration was more common than economically-driven migration, with women making up an even larger part of migration for marriage.

In the 1990s, spontaneous migration for business/work became the main driver of migration. The 4th National Census in 1990 showed that 50.16% people migrated for business/work, and 32.49% for marriage, staying with relatives and friends, accompanying family members and other social reasons. Over that period, economically-driven migration accounted for more migration than non-economically-driven migration and this truly explained the migration surge in 1990s. Rather than being passively pushed to live with their husbands, women migrated to cities in an active search for employment and development opportunities (Yang Ge and Duan Chengrong, 2007).

Data from the 5th National Census in 2000 and the 1% Demographic Sampling Survey 2005 showed that upon entering the 21st century, the proportion of migrants for business/work remained around half of the total. Those for marriage and staying with relatives and friends declined further, to around 8% to be exact, and the proportion of migrants accompanying family members slightly increased to nearly 14%. Compared with the figure in 2000, migration due to relocation/home moving was up 2 percentage points (Yang Ge and Duan Chengrong, 2007).

In the 21st century, apart from being financially driven, migration also has the following features: when they are better off in receiving areas, migrants begin considering having their family members migrate to the city, so migration for that reason has accounted for a higher proportion. Meanwhile, expansion of big cities and development of small ones has attracted a large number of people seeking a new place to settle (Yang Ge and Duan Chengrong, 2007). Positive policies such as hukou system reform and integration of urban-rural public services have created an enabling environment for market-driven female migration. The report at the 18th CPC National Congress 2012 put forward the strategy of integrated urban-rural development and equalization of basic public services. Developed eastern provinces have already been actively promoting hukou reform: Shandong province’s strategy of promoting hukou reform, covering all regular urban residents with basic services like education, healthcare and social security, and facilitating orderly citizenization of rural migrants; Fujian’s plan of providing basic public services to regular residents instead of just registered residents, extending services from the urban community to small towns and villages and promoting equal allocation of public resources; Guangdong’s idea of breaking geographical and hukou restraints, improving relevant systems so that non-local workers can get an urban hukou and participate in social management by accumulating points, and enhancing education and training of a new generation of non-local workers.

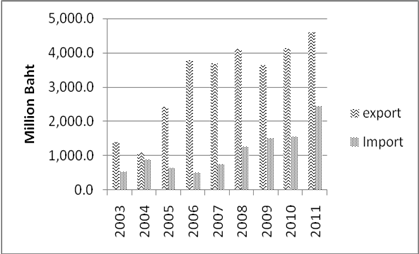

Chart 3 Why People Migrate

Source: Data in 1987, 1990, 2000 and 2005 from Duan Chengrong (Duan Chengrong, Yang Ge et al., 2008), data in 2011 from China's Migrant Population Development Report 2012; charted by the author.

3.2 How family roles affect migration

Acting in accordance with the social norms of “men are responsible for external matters while women for domestic chores”, men go out (to the public areas) to earn a living and support the family while women wash clothes, make dinner, and take care of children and elderly relatives at home (in private areas). Although the traditional perception has been eroding in the market economy, in poor and rural areas where the market mentality is prevalently weak, this perception confines female migration to a certain degree. Ning Benrong (2010) believes that conventional perceptions that go against women are deeply entrenched, creating a great many career development hurdles. On the one hand, such perspectives about gender roles as “men are dominant while women subordinate” and “men are masculine and women soft” make women misperceive themselves and think they are not as capable or intelligent as their counterparts. On the other hand, traditional thoughts about career development in organizations (companies, enterprises, etc.) fail to provide a favorable environment for women to develop professionally. Zhang Chuanhong (2010) used sociological research methods and studied the influence of “family migration” on the family itself. It is concluded that “family migration” has liberated migrating couples from the conventional perceptions about gender, and somewhat changed labor division patterns in the rural migrating families. After moving to urban areas, women earn higher income, but their income still lags far behind that of men’s. Women’s burdens of household chores are reduced with greater participation of husbands.

3.3 How marriage Affects Migration

Marriage is an important factor influencing rural female migration. Once married, women have more roles to play than men, such as keeping the family in order (wash clothes, cook dinner and take care of children and in-laws) and continuing the family line (bear children). Therefore, for men, marriage “symbolizes the obtainment of identity as a full community member”, but for women, marriage means separation from their maiden home. Social division of gender in the new family implies that rural women will mainly work at home (private areas) and this means a loss of personality. Female migrant workers are just passing faces in the city. When the time comes, they have to leave to get married and play the mother’s role (Gao Jingzhu, 2007). This shows that marriage is hindering female migration as childbearing and household chores are more time and energy consuming for women, thereby negatively impacting upon their migration. But marriage itself is not much of a barrier to female migration (e.g. before the baby is born). Huang Runlong et al. (2000) indicate that the rate of early marriage among female migrants is high, and under age 54, there are more female migrants with a spouse than male ones. Different from single female migration, the migration of married women (esp. middle-aged ones) has more to do with accompanying the husband to the city and hence the characteristics of migration as a household. Middle-aged women who follow their husbands make up a large part of family migration populations. Whether the husband goes or not has the most impact on rural women when considering migrating. A study of Feng Chunmei (2012) indicates that younger women migrate mainly for more development and experience opportunities, while middle-aged ones, besides being influenced by higher pay, are more likely to accompany husbands than younger ones.

The dual urban-rural hukou system determines the fact that rural populations cannot enjoy the same social resources as their urban counterparts when they migrate to the city. They have to shoulder huge psychological pressures and social burdens that weigh heavily on their mind, body and even life. The easiest way to ease up, improve their social standing and satisfy material needs is to marry a local and change hukou. Marrying a fellow villager or marrying a migrant from another town is also a choice for many female migrants. Meanwhile, the very nature of migration is what causes marriage instability. Premarital sex among migrant populations is very common. Unplanned pregnancy, among other factors, is also a reason for migrants to get married (Huang Runlong and Yang Laisheng, 2000: p42).

Since the 1990s, nuclear family migration has been on the increase, becoming one of the most important trends in China’s change of migration structure (Duan Chengrong, Yang Ge et al., 2008).

4. The effects of gender roles on women’s and men’s experiences of being left behind

4.1 Bigger say of women within the family

When their husbands migrate for off-farm jobs, left-behind women take over many agricultural production activities such as sowing, applying fertilizers, spraying pesticides, harvesting and herding. Those activities are precisely what highlight the important role of left-behind women in household production and increase their bargaining power within the family. Women can make decisions on major family affairs independently or jointly, thus increasing their standing in the family significantly. Husbands’ migration reconstructs to a large extent the traditional gender-role-based social division, thereby influencing left-behind women’s family status. First, within the family, all the household chores are on women’s shoulders, such as daily housekeeping, taking care of the elderly and raising children. Second, outside the family, farm work originally shouldered by the husband or the couple is now women’s duty. In this respect, women’s obligations have both internal and external dimensions, enabling them to be the major household decision-makers. But women are not as experienced in farming as men, so they sometimes fail to make a good decision. Many women also ask their husbands’ opinions. Autonomy in management leads to enormous enthusiasm to learn how to farm. This process can help women gain greater independence of finance, mind and capacity (Cheng Zhiguang and Yang Juhua, 2012).

The processes of industrialization and urbanization have pushed left-behind women to the front stage of rural life. Although they have brought pressure and hardship to rural women, changes in social life have created favorable conditions and provided historic opportunity for the reconstruction of subjectivity. According to the surveys in Jiangsu, Hubei and Gansu, where relatively large numbers of outflow migrants are from, women have never been more needed in rural China to play such an important role in social life as today. Women have become key players in grassroots democracy and autonomy. Female citizens’ democratic participation means that this once disadvantaged group in rural areas has gradually become a dominant player in rural political life, and has shown enormous subjectivity and importance like never before (Wu Yiming, 2011: p56).

4.2 More financial rights within the family

With the absence of husbands, 71.4% of left-behind women hold the purse strings of the family. If we look into the change of the percentage of women managing family finances before and after their husbands migrate for work, we can see that 50.0% of left-behind women begin taking control of the financial well-being of the family after seeing off their husbands. Actually, this improves their status in making economic decisions, which is at the core of the family rights, hence automatically enhancing women’s standing with the entire family (Wu Huifang and Ye Jingzhong, 2011: p107).

“Rural husbands going out for work has reconstructed the traditional gender-based social division of labor to a large extent and has affected the family standing of left-behind women” (Chen Zhiguang and Yang Juhua, 2012: p75). Without the husband around, the wife must solve problems independently. So compared to women whose husbands are at home, left-behind women are more independent. “According to the survey, 65.2% of left-behind women never spoke of their personal troubles or family difficulties on the phone with their husbands; instead, they chose to handle those problems on their own” (Wu Huifang, 2011: p109).

4.3 Increased decision-making power within the family

Wu and Ye (2011) believe that the phenomenon of the husband going out for work and the wife staying home has lifted the geographical restrictions of the rural gender division of labor for the first time, and led to a change of gender relations. The family strategy of the husband going out and the wife staying in has promoted an increase in women’s decision-making power in the family due to geographical separation, women’s autonomy of action and recognition of partners’ individuality. Gender relations in rural China are more and more equal, increasingly shaking the traditional gender norms. In the traditional households in rural China, husbands are dominant breadwinners and wives subordinate homemakers. Since the rural labor force began moving to the cities in 1980s, however, the traditional way that couples divide their work has been constantly changing in rural communities. The unitary gender division of labor comes in different forms but these are the same in nature, such as those mentioned above or the idea that “the men plough and the women weave”. This has evolved into diverse patterns of gender division of labor or different ways of dividing labor in different life cycles of the family. Among all the new ways, the most attractive one is “the men work off-farm and the women plough”, i.e. men go out and work in the city while women continue engaging in farm work and taking care of family.

The income growth of male breadwinners does not make left-behind women less powerful in making family decisions; instead, left-behind women engage more in family farm work and handle more family resources, so their decision-making power is prominently strengthened and family standing improved. In general, the new labor division model of “male migrating and female staying at home” serves as a double-edged sword for left-behind women in that it both increases the burden of family chores and farm work and creates an enabling environment for improved family decision-making power (Chen Zhiguang and Yang Juhua, 2012: p70). Compared to non-left-behind women, those left behind have more time to dedicate to their children. Due to migration of fathers and heavy work of mothers, however, they have a hard time attending to their children’s education time and quality. (Zhang Yuan, 2011: p46)

4.4 Security and loneliness of left-behind women and the elderly

Geographically, rural left-behind women live in a disadvantaged community in a modernized society; and gender-wise, they belong to a vulnerable group in a traditional society. Therefore, they are the least advantaged group in the modern society. Their sense of security is far lower than that of non-left-behind women and they more often fall prey to bullying and harassment. In the survey, many left-behind women say that when their children or parents-in-law get sick at night, they feel extreme fear and helplessness, because late at night, it is hard for them to get someone to help, and they dare not take the patient out to find doctors or send them to hospitals, or to leave the patient at home and seek doctors alone. Suffering from this, rural left-behind women feel less and less secure and even insecure, and their sense of security is in crisis (Sun Kejing and Fu Qiong, 2010: p31) .

With children away for off-farm work, there is no one taking care of the left-behind elderly when they get sick, so sometimes they are not sent to a doctor in time, left unattended during illness or receive no quality care (He Congzhi and Ye Jingzhong, 2010: p52). Medical conditions in the rural communities still lag far behind with only one/two “barefoot doctors” or private clinics in every community. In some neighborhoods, people live in a scattered way, so senior citizens would have trouble seeing a doctor if they live in remote villages. In such cases, with the absence of children, when the elderly suddenly fall ill, they often fail to get medical help in time because nobody knows the situation or escorts them to the hospital. It is more common for empty-nest, widowed, and older left-behind parents to fail to get medical attention in time. In parallel, their personal safety is also potentially at risk as their probability of encountering unexpected safety-threatening events is higher than that of the non-left-behind. The percentage of the left-behind elderly who become victims of theft, cheating, accidental injury and bullying (beating/scolding) is remarkably higher than that of the non-left-behind (He Congzhi and Ye Jingzhong, 2010: p52).

5. Social exclusion of migrant populations

5.1 Employment and female migrants

In China, there is a greater gender balance among migrant populations and family migration is replacing the traditional individual migration and staying behind as one of the major patterns of migration. But judging from employment and income, the two key indicators that evaluate economic activities, we can see that women are still in a disadvantaged position.

The 1% Demographic Sampling Survey 2005 showed that more men were employed than women. 20.67% of the migrant workforce was unemployed at the time of the survey. The percentage of women who were unemployed was higher than that of men, and accounted for 29.77% of the total unemployed migrants. Why? Many women move to cities to accompany and take care of their family members rather than seeking job opportunities. 88.36% male migrants were employed at that time (Duan Chengrong and Yang Ge, 2008).

In 2011, among all male and female working-age migrants, 87.1% were employed, 1.6% unemployed and 10.2% homemakers. 77.5% of female migrants were employed, 19.4% homemakers and 1.8% jobless/unemployed (Dept. of Services and Management of Migrant Population, NPFPC, 2012).

In 2011, 80% of the employed migrants were concentrated in 5 sectors, 37.4% in manufacturing, 18.1% wholesale and retail, 9.9% accommodation and restaurants, 9.8% social work, 7.1% construction (Dept. of Services and Management of Migrant Population, NPFPC, 2012).

Liang Hualin (2007) conducted a questionnaire with female rural migrants in China’s central and western regions such as Shanxi, Hunan and Gansu provinces. It was found that 37.8% women chose to be a “waitress”, 7.5% a “housekeeper/baby-sitter”, 4.4% a “construction worker”, 6.8% a “foreign company worker” and 14.7% a “worker in other sectors”. We can see that after moving to cities, female rural migrants mainly engage in low-income and low-prestige tertiary industry and domestic service sectors. The employment rate and quality of women migrant workers are below men’s and most women are hired by private employers or work as freelancers.

According to the Migrant Worker Survey Data 2011, median and mean monthly salaries of rural migrant workers were 2,000 and 2,240 yuan in 2011. Salaries of male migrant workers were 34% more than females’. And the salaries increased faster for migrant workers at age 16-30, reaching a peak at age 31-35, and then declined after age 50. Salaries of female migrant workers began declining after age 30 while for males this began to occur at age 35 (Dept. of Services and Management of Migrant Population, NPFPC, 2012).

Song Yueping (2010)’s questionnaire and quantitative analysis showed that all things being equal, female rural migrants had to spend more time searching for jobs than men. In other words, the probability of male migrants ending their search for jobs was 13.2% higher than for females. Men had 1.58 times more opportunities to find well-paid jobs (≥RMB 2,000). Marital status had no significant effect on job opportunities of men, but negatively influenced women’s chance to get hired. As the estimates indicated, employers believed that married women could not spend as much time and energy at work as single women, and being deeply influenced by the traditional perception that “men go out and women stay in”, they positioned married women as homemakers.

Chart 3 Salaries of Migrant Workers: Gender/Age

Source: Dept. of Services and Management of Migrant Population, NPFPC, 2012, p32.

Song Yueping (2010) surveyed 88,692 rural migrants in 2010. According to her data analysis, it took male migrants an average of 63 days to get a job and females 60 days. Male migrants were concentrated more in high income employment, e.g. they could be self-employed or simply become an employer. It took more time, however, to find such jobs. Women usually worked as employees and family helpers. The time spent searching for such jobs was relatively short (Table 1). The opportunity of men getting a highly paid job (≥RMB2,000) was 1.58 times more than for women.

Table 1 Search Time for Different Employment and Income

|

Type |

Time (day) |

Average Monthly Pay |

Female (%) |

Male (%) |

|

Employee |

49.54 |

1721.91 |

73.9 |

70.1 |

|

Family Helper |

61.27 |

1442.81 |

2.1 |

0.6 |

|

Self-employed |

70.79 |

1827.45 |

19.8 |

23.2 |

|

Employer |

71.13 |

2820.49 |

4.2 |

6.1 |

Source: Song Yueping (2010).

Marital status does not have a prominent impact upon male migrants’ employment opportunity. But its impact upon female migrants is obviously negative. The statistical results show that employers believe that married women cannot dedicate their time or energy to work like unmarried women. Following the traditional concept that “men are responsible for external matters and women internal ones”, the employers position married women more as housewives.

5.2 Social exclusion and female migrant populations

5.2.1 Identity

Reduced social exclusion of migrant populations means their greater integration into society and awareness of their own identity. In detail, social integration of migrant populations has economic, social, and physiological/cultural dimensions (Tian Kai, 1995), and the adaptation to the three dimensions is progressive in nature (Zhu Ban, 2002).

Li Hong, Li Shiguang et al. (2012) believe that the establishment of self-identity is a multi-dimensional and progressive process influenced by individual families, urban systems and social participation. Their data analysis of the sampling survey of the migrant population in 106 cities nationwide in 2011-2012 showed that in terms of self-identity, migrants’ wish to integrate was obviously higher than their inward identity. About 80% of migrant populations wished for greater integration, while only 23% wished for greater inward identity. The difficulty of self-identity lies in the conflict between individual identity constructs and social constructs; therefore diversities and complexities from the perspective of internal conditions, the external environment and policy constructs should be thought through.

Table 2 Components of Migrants’ Self-identity

|

Problems |

Factor Loadings |

|

|

Factor I: Identity Wish(39.21%) |

Ⅰ |

Ⅱ |

|

1. I follow the changes of the city where I live |

0.76 |

- |

|

2. I love the city where I live |

0.75 |

- |

|

3. I’m willing to blend in |

0.74 |

- |

|

4. I feel that the locals always look down on non-locals |

0.71 |

- |

|

Cronbach α = 0.77 |

|

|

|

Factor II: Inward Identity(24.81%) |

|

|

|

5. Locals are willing to accept me as one of them |

- |

0.70 |

|

6.No matter how much I earn, I can never become a local |

- |

0.69 |

|

Cronbach α = 0.59 |

|

|

Note: % in the bracket explains the variations of factor analysis;

Source: Li Hong, Ni Shiguang and Huang Linyan (2012).

Wang Mingxuan and Lu Jiehua (2009) argue that terrible psychological identity reflects the mental state of migrants in a socially excluding society. Female migrants suffer dual exclusion socially and culturally due to their low social status. As a result of limited access to recourse, humble standing and low cultural quality, they often remain silent and this reinforces the unequal treatment they get in receiving areas, thus falling into the vicious circle of unfair treatment and infringed rights and interests.

The hukou system plays an important role in resource allocation and the dual urban-rural structure, and is also the institutional root for female migrants to have negative gender identity. Female migrants contribute their youth and labor to urban development, but they are not correspondingly rewarded. The strict residential limit caused by the hukou system reduces women to an awkward position where they are not accepted by the receiving city and yet are not reconciled to returning to rural areas. Therefore, they have to accept their negative identity unwillingly.

5.2.2 Education and health

Education. Level of education, undoubtedly, has a great influence on the job hunt of migrant workers. Chen Jinmei, Lin Liyue et al. (2012) studied the characteristics and differences of employment based on their survey of the female migrant workers in Fujian province. The interviewees were separated into 5 groups according to their education level: “illiterate/half illiterate”, “primary school”, “junior high”, “senior high/middle vocational school” and “junior college and above”. It is found that the higher the education level is, the higher the job level, likelihood of finding jobs in formal sectors and probability of being well-paid will be after migration. Poorly educated female migrants often find themselves encountering wage arrears, high labor intensity, fragile jobs, low rates of professional training and weak desire to get trained. Education level has a positive effect on the improvement of female migration. But Duan Chengrong, Zhangfei et al. (2009) indicated that the education level of male migrants was higher than that of female ones. Most female migrants studied in junior high schools. But only 60.10% went to senior high schools or institutions of higher learning. Female farmer workers (rural hukou) were less educated than urban female migrant workers. Less than 1.5% of female farmer workers were highly educated. A low level of education directly determines their fate of doing labor-intensive and low-end work, and shortage of knowledge leads to low awareness of law and rights, weak ability to protect themselves socially, limited cultural acceptance, and restricted consciousness and capacity to seek social support.

Access to schooling is the first educational issue of migrant children that causes extensive concern. With the increased number of migrant children, the availability and affordability of schooling, access to quality schools, and difficulty in furthering studies in receiving areas have been heavily researched, among all the problems endangering schooling of migrant children. Lv Shaoqing and Zhang Shouli (2001) analyzed a survey on the schooling of migrant children in Beijing. They concluded that basic education of migrant children was excluded from the urban-rural education system, and was forced to settle outside the system through spontaneous market-based approaches. But there is a severe shortage of market-based education provision and effective demand (ability to pay). Migrant children’s rights to education are thus lost, and equity and integrity of compulsory primary education compromised. Duan Chenggrong and Liang Hong (2005) found, based on their study of the 5th National Census, a high dropout rate of school-age migrant children, migrant children’s inability to adapt to new schools and regional differences and difficulty of receiving schools, and offered their suggestions to solve those issues. Du Yue and Wang Libing (2004) believes that household income of urban migrant families is what restricts their school-age children from receiving education. In particular, various kinds of educational expenses are “thresholds” that keep migrant children out of public schools. Wang Di (2004) argues that although some of the migrant children in receiving areas find their way to public schools and local students’ classes, many are enrolled in special classes and schools where there are many classes for children of migrant workers. Even in the case of public schools, children of migrant workers are discriminated against and excluded by teachers and classmates. Inadequate educational facilities in migrant schools give rise to inequity during the process of learning. Shen Xiaoge and Zhou Guoqiang (2006) conducted a survey to see what percentage of migrant children and their urban fellows were going to senior high schools after finishing junior high. It was found out that in 2004, only 10.74% of the migrant children in Guangdong province went to senior high, while 41.24% of the urban children went to senior high schools; in Shenzhen, only 0.97% of the migrant children went to key senior high schools, while for urban children the figure was 15.88%. Other studies also show difficulty of migrant children in continuing with their education (Sun Hongling, 2001).

Unequal educational status of migrant children can be attributed to a series of system arrangements under the dual urban-rural structure. Feng Bang (2007) argues that the die-hard dual urban-rural hukou system is the reason that migrant children undergo exclusion. Because the educational financial input and admission system in China are derivatives of hukou system, unequal financial investment in education leads to an unequal educational process for migrant children: the government gives a lot of financial and material input to public schools while giving almost no support to migrant schools. Lacking governmental assistance, migrant schools are ill-equipped and even fail to meet the most basic requirement of primary education. Meanwhile, the unfair admission system leads to unequal educational results: in some receiving areas, according to relevant government rules, local hukou students are required to sit senior high school entrance exams and college entrance exams (Gaokao). But because their mothers are all in the receiving areas, children are reluctant to go back, thus facing employment issues when they are denied the chance to go to senior high schools. And Gaokao policy clearly specifies that: “All Gaokao candidates must return to the district in which they are registered and apply for the exam.”

In 2012, the General Office of the State Council forwarded the Notice on Opinions of How to Enable Children of Migrant Workers to Sit in Local High School Entrance Exams after Receiving Compulsory Education originally issued by the Ministry of Education and other relevant ministries. The General Office asked local governments and educational departments to ensure that children of migrant workers enjoy equal rights to receive education and pursue further studies, to promote an orderly and reasonable population flow, to balance education demands of children of migrant workers and capacity of local educational resources, and to facilitate relevant work in a positive and steady way. Heilongjiang, Shandong, Fujian, Jiangxi and Anhui have already unveiled relevant policies. Other provinces and municipalities are conducting research and formulating plans as well.

Health. According to Zhen Zhenzhen and Lian Pengling (2006), when rural residents migrate to cities, their health behavior and use of reproductive health services change for the better under the influence of urban residents. For example, compared to rural residents of a similar age, migrant women are in command of more reproductive health knowledge and more conscious of health and fitness. Moreover, they are more concerned with pregnancy care and more likely to give birth at a hospital. Huang Honglin and Liu Suoqun (2004) argue that the fertility rate of the migrant population is lower than that of the rural population, and extremely close to that of non-migrants in urban areas. The low fertility rate, however, is caused by economic pressure and poor environments. The traditional attitudes towards having children such as favoring sons over daughters and continuing the family line by having sons are deeply entrenched in some people’s minds.

Risk of exposure to HIV/AIDS among the migrant population is high. According to statistics, among the known HIV-infected patients, the migrant population makes up a large part (Ding Xianbin, Chen Hong et al., 2006). In 2008, among the known HIV-infected patients in Yantai city, 70% were migrants. Some of them were infected with the virus in sending areas and moved to Yantai for off-farm work or marriage. Some were infected though highly dangerous sexual behavior during frequent migration. Since its first HIV/AIDS case was revealed through testing in 1985, Wenzhou city has detected more infection cases, with the migrant population comprising 72.5% of the infected; and among the infected persons detected in Xiamen city in recent years, the migrant population has accounted for 80.3% (Liu Pan and Tang Xianxin, 2010).

The risk of getting infected relates to the professions that the migrant workforce engages in. In the sex service sector, prevention of HIV/AIDS has become a focus in preventing the disease both in China and foreign countries. Many sex workers are single women from rural areas. As they are poorly educated, they are at a disadvantage concerning self-protection, so face a higher probability of getting STDs and HIV/AIDS (Zhen Zhenzhen and Lian Pengling, 2006). Meanwhile, the absence of government monitoring of migrants’ health condition, mobility of the migrant population and the long latent period between exposure to HIV infection and the onset of AIDS make it very difficult to control the spread of HIV/AIDS among the migrant population. Once HIV-infected women return to their hometown, get married and give birth, there will be more people infected with the virus. This will cause a huge blow to the economic situation of the family, their children’s reproduction/education and family harmony/development.

5.2.3 Social security