2013—The 7th China-ASEAN Forum Poverty3

7. Conclusion

Since reform and opening-up, and through industrialization and urbanization, urban China has attracted a large number of rural surplus workforces. The unprecedented large scale of migration gives the poor rural population a chance to find development opportunities in urban areas. This institutional arrangement is exactly what helps billions of people out of poverty. Some institutional barriers and aspects of social exclusion, however, stand in the way of their full integration into cities. Elimination of social exclusion, introduction of more inclusive migration systems and policies and creation of enabling environments are of great significance to China’s goal of building a moderately prosperous society (Xiaokang society) in a holistic way. The literature review of this paper finds the following:

7.1 Structural change of migrant populations

Compared with the time before the 21st century, the gender mix of the migrant population is more balanced. In the 1980s, migrants were primarily men.

Drivers of migration have also changed compared with the time before the new century. In 1980s, marriage and staying with relatives and friends were major drivers while economic reasons minor ones; now migration is more market-oriented and less socially-driven.

Moreover, there is more family migration than individual migration. Migration is more of a family behavior now. This shift is gradually changing the phenomenon of “staying behind”. The new “left-behind” population is on the decrease.

Female migrants are younger than male ones.

7.2 Multiple effects of migration and gender roles on the left-behind

Migration has changed the traditional domestic division of labor characterized by such patterns as “men are responsible for external matters and women domestic ones”. For a long period, the traditional pattern was replaced by the pattern of “men do off-farm jobs and women farm in the fields”. As more and more left-behind women engage in household agricultural production and operation activities, they have to make all kinds of production-related decisions and manage domestic finances. Their family status is thus improved and so is their power of managing village affairs.

With industrialization, urbanization and migration, rural women’s values and family members’ attitudes towards migration are changing positively. Before the new millennium, mostly, men went out to find jobs while women stayed home. With improved education and health service provision by the receiving governments and development of new rural cooperative medical care and rural old-age insurance systems in sending areas, the costs and thresholds for family migration are further reduced.

7.3 Female migrants still suffer from multiple from of social exclusion

In respect of employment, female migrants take more time to land a job. Their employment rate is lower that of men, and so are their salaries.

Despite the improved social identity of the migrant population, compared to their wished-for social identity, the level of social identity is still very low. Female rural migrant workers are still widely labeled “factory girls” (Dagongmei) and differentiated from urban women in terms of status.

The government has put a lot of energy into widening access to compulsory education in receiving areas to migrant children, and the problem has been basically solved. But the Gaokao candidates still need to return to where they are from and sit for the exam. This is one of the biggest sources of social and educational exclusion against the children of migrant workers.

Although the rural medical care insurance system has been established in rural areas in a comprehensive way, due to the limitations of the hukou system, the percentage of rural migrant workers partaking of urban medical insurance is extremely low and the number of migrant workers receiving rural cooperative medical care is far less than that of farmers. Even if they do join the rural cooperative medical care system, they still need to return to where they are from in order to be reimbursed for hospitalization expenses in the receiving areas.

The hukou system is the biggest institutional barrier causing social exclusion of migrant population. Inequities in the availability of education, health, social security and housing are handicapping rural migrant workers from getting urban citizenship.

Migration has enhanced left-behind women’s political standing. But in receiving areas, their level of political participation has not been improved. In receiving areas, in particular, many migrant workers do not ask for a work contract, so their legitimate rights and interests cannot be effectively ensured. And the ensuing labor disputes will be a factor against protection of their rights.

7.4 China’s migration policy is entering a whole new era

Analysis of migration policy changes shows that the 1990s policy mainly restricted migration of rural migrant workers to prevent disorderly inflow into cities. Since the start of the 21st century, government has been lifting restrictions on rural migration. Policies to protect rights and interests of rural migrant workers have also undergone great changes, from protection of their wages and their children’s rights to compulsory education to expansion of social security coverage, including medical insurance, housing and old-age security.

Provinces are exploring ways to reform the hukou system, and some places are piloting relevant projects. As the central government proposes to develop urbanization and realize integrated urban and rural development, we have every reason to believe that this will usher in a turning point for the migration-restraining hukou system. However, studies focusing on gender dimensions are very insufficient. Gender dimensions should be incorporated more into later studies and policies.

References

1. Academy of Macroeconomic Research, NDRC (2012). “Studies on the Strategy of Urbanization”. Quoted from Sina Finance, Dec. 10, 2012.

2. Chen Jinmei, Lin Liyue and Zhang Liqiong (2012). “How Different Are the Jobs of Female Migrants with Different Level of Education: Take Fujian Province as An Example”, Yunnan Geographic Environment Research. No. 4.

3. Cui Chuanyi (2007). “On the Change of Chinese Rural Migration Policy Patterns”, Yue Jinglun & Guo Weiqing, Comments on China’s Public Policy (I), Shanghai Renmin Publishing House.

4. Department of Services and Management of Migrant Population, NPFPC (2011). The 2010 Report on China's Migrant Population Development. China Population Publishing House.

5. Department of Services and Management of Migrant Population, NPFPC (2011). The 2012 Report on China's Migrant Population Development. China Population Publishing House.

6. Ding Xianbin, Chen Hong, Pan Chuanbo et al. (2006). “An Analysis of Migrant Population’s Knowledge about and Attitudes towards HIV/AIDS and Their Highly-dangerous Behaviors”. Public Health in China. No. 11. p. 1293-1294.

7. Du Yue, Wang Libing and Zhou Peizhi (2004). Basic Education of Children of Migrant Population: Policy and Reform, Hangzhou University Publishing House.

8. Duan Chengrong and Liang Hong (2005), “Research on the Compulsory Education of Migrant Children”. Population and Economics. No. 1.

9. Duan Chengrong, Yang Ge et al. (2008), “Nine Trends of Migration Since Reform and Opening-up”. Population Research. No. 6.

10. Duan Chengrong, Zhangfei et al. (2009). “Research on China’s Female Migration”. Collection of Women's Studies. No. 4. p. 11-19.

11. Duan Chengtong and Yang Ge (2008), “Status Quo of China’s Migrant Population”, Collected Papers at the International Seminar on China’s Social Service Policy and Household Well-being. Beijing.

12. Feng Bang. “Education Equity of Migrant Children: From the Perspective of Social Exclusion”. Jiangxi Educational Science. Vol. 9, 2007.

13. Feng Chunmei. “Rural Female Migration From the Perspective of Family Migration”. Anhui Agricultural Science. Vol. 12, 2012.

14. Gao Jingzhu. “On Identity of Female Migrant Workers during Transition Period: Reading Pan Yi’s Female Factory Workers”. Academic website. Apr. 20, 2007.

15. Jacka, Tamara (2006). Rural Women in Urban China: Gender, Migration and Social Change. 2006 Ed. Translated by Wu Xiaoying. Jiangsu People’s Publishing Ltd.

16. Li Bohua, Song Yueping et al (2010). ”Report on the Living and Development Conditions of Migrant Populations: Based on the Investigation on Key Receiving Areas”. Population Research. Vol. 1. 2010.

17. Li Hong, Ni Shiguang and Huang Linyan. “Self-identity of Migrant Population: Status Quo and Policy Suggestions”. Academic Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Science Ed.), Vol. 2, 2012.

18. Liang Hualin (2007). “On Female Rural Migration and Public Policy Options from the Perspective of Gender: Take Rural Women in China’s Central and Western Regions”. Academic Journal of Shanxi Party School. No. 6. p. 26-28.

19. Lin Jiabin (2012). “Some Thoughts on Rural Migrant Workers’ Attainment of Citizenship”. Collected Papers at the 76th Internal Forum on China’s Reform. Dec. 4, 2012. Quoted from DRC website.

20. Liu Wei and Shen Yujing (2012). “Integration of Rural Migrant Workers into Urban Areas: Social Exclusion and Social Acceptance”. Economic Research Guide. No. 11.

21. Lv Shaoqing and Zhang Shouli. “Education for Migrant Children under the Differentiated Urban and Rural System: A Survey on the Migrant Schools in Beijing”. Strategy and Management. Vol. 4, 2001.

22. Ning Benrong. “Women’s Career Development in the New Period: Difficulties and Reasons”. Northwestern Population. Vol. 4, 2005.

23. Sun Hongling. “On Education Equity of Migrant Children during the Transition Period”. Educational Science. Vol. 1, 2001.

24. Tian Kai. “On Adaptation of Rural Migrant Workers to Urban Life: Survey, Analysis and Thoughts”. Social Science Research. Vol. 5, 1995.

25. Wang Di. “Survey on Educational Issues of Migrant Children”. Population Science. Vol. 4, 2004.

26. Wang Mingxuan and Lu Jiehua. “On Gender Indentity of Female Migrants in Contemporary China”. China Population Today. Vol. 1, 2009.

27. Wang Runlong and Yang Laisheng. “On Marital Status of Female Migrants and the Influence Factors”. Academic Journal of Nanjing College for Population Program Management. Vol. 1, 2000.

28. Wu Huifang and Ye Jingzhong (2010). “How does Absence of Husbands Affect Rural Left-behind Women”. Academic Journal of Zhejiang University. No. 3.

29. Wu Yiming (2011). “Participation of Left-behind Women in Village Governance and Its Influences: A Study Report from Jiangsu, Hubei and Gansu Province”. Academic Journal of Nanjing Normal University (Social Science Ed.). No. 2. p. 52-57.

30. Xu Chuanxin (2009). “Women’s Participation in Politics in the Context of Extensive Migration of Male Workforces: A Comparative Analysis of Left-behind Women and Non-Left-Behind Ones”. Study and Practice. No. 5.

31. Yang Ge and Duan Chengrong (2007). “On the Trend of Changes in the Migrant Patterns over the Past 2 Decades”. Renmin University of China.

32. Yang Juhuang. “Differences of Urban and Rural Areas and Differentiated Identity: On Social Security of Migrant Population. Population Research. Vol. 5, 2011.

33. Zhang Chuanhong. “How Does Rural-urban Migration Affect Household Division of Labor”. Academic Journal of Agricultural University (Social Science Ed.). Vol. 3, 2010.

34. Zhen Zhenzhen and Lian Pengling (2006). “Migration of Workforces and Health Issues of Migrants”. China’s Labor Economics. No. 1. p. 82-93.

35. Zhu Li. “On Adaptation of Rural Migrant Workers to Urban Life”. Jianghai Academic Journal. Vol. 6, 2002.

Chapter 5: Poverty and Protection of Rural Left-behind Children in the Context of Urbanization

ZHANG Xiaoying, GAO Rui, WANG Erfeng

1. Introduction

Although there is no unified definition of urbanization, we know that it is a process, not a result. Urbanization is characterized by increasingly open cities and the free flow of resources between rural and urban areas. While urbanization can promote human development, it can also have negative effects. If urbanization’s negative impact on the Latin American countries has been the transfer of rural poverty into cities and a large number of slums, then the noticeable negative impact of urbanization on China's rural areas is the generation of a “left-behind population” – children who remain in the countryside while their parents go to work in the cities - which is an obstacle in the prevention of the intergenerational transmission of poverty in rural areas. Since 2002, scholars in various areas have been studying the phenomenon of left-behind children, and have discovered many problems among this group in learning and living, including provision of care and good mental health. Focusing on urbanization under the children's multidimensional poverty analysis framework of Shang Xiaoyuan and Wang Xiaolin (2012), this paper provides a comprehensive overview and analysis of the current situation of 10-18-year-old left-behind children in rural areas in handling family, schools and social activities. Generally speaking, "being left behind" has a significant negative impact on rural children. Their rights to survival, health, protection, development and participation lag behind those of other children, especially among girls and in poverty-stricken areas. However, left-behind children are superior to other children in some aspects, for example, fewer left-behind children express being tired of school. It indicates that in poor areas, most children still believe that knowledge can change their destiny and that they cannot shake off poverty unless they work hard.

2. Impact of urbanization on left-behind children in rural areas and its characteristics

The term "left-behind children" first appeared in the article "Left-behind Children" published in 1994. At the time, "left-behind children" mainly referred to the children left at home when their parents went abroad to work or study (Yi Zhang, 1994). Recently, the term "left-behind children" became familiar to the public from the article "Left-behind Children Need More Love" (Sun Hua, etc., 1997) published in 1997. The article analyzed how when left-behind children lacked adequate supervision, their ability for self-management decreased, and juvenile crime increased which had become a threat to safety. In 2002, the Guangming Daily printed an article titled "The Education Problem of Rural ‘Left-behind Children’ Needs to Be Solved". Since then, media began to keep an eye on the issues of left-behind children (Zhou Fulin, etc., 2006). Since 2005, scholars in the field of psychology, sociology, education and economics published articles expressing concern about this new vulnerable group, and left-behind children became a hot topic in academics.

The problem of left-behind children in China resulted from the process of urbanization. The impact of urbanization on rural children began with its impact on their parents. As cities continue to open up, more and more farmers bid farewell to rural areas and come to work in the city. This created three major groups of rural children, depending on policy systems, family environment, and other limiting factors: “left-behind children” living with a single parent or relatives; “migrant children” moving together with their parents, and the children still living with their parents in rural areas. These groups are flexible, and “left-behind children” often transfer between the “left behind” and “migrant” groups as government policies and their parents’ status and economic capability change. According to current studies, "being left behind" has a serious negative impact on children, especially on children’s self-confidence and communication skills. (Zhou Zongkui, etc., 2005). However, as children change as they grow up, the impact of "being left behind" can reveal some positive effects. For example, some "left-behind children" have a stronger ability to take care of themselves than their peers.

3. Analytical framework and sample selection of this paper

3.1 Analytical Framework

Children who are poor are not necessarily from poor families. Rural labor migration has had positive effect on increasing rural incomes, alleviating rural family poverty and improving farmers' family welfare (P Yanping, 2011). In many cases, however, alleviation of family poverty does not inevitably result in alleviation of child poverty. Sen (2012) believes that "other competing demands of a family, the lack of child nutrition and health knowledge, the limitations of market mechanisms in the provision of public services and gender inequality all affect the impact of income growth on child development. “In the countryside of many developing countries, when an accident occurs, parents often first require their children, especially daughters, to drop out of school (Hillman etc., 2004). Therefore, unlike adult and family poverty, child poverty is manifested in many ways: a relatively high rate of malnutrition, a high child mortality rate, social discrimination and exclusion due to poverty and serious feelings of inferiority (Shang Xiaoyuan, Wang Xiaolin, 2012).

Based on the multidimensional poverty analysis framework used by Shang Xiaoyuan and Wang Xiaolin in the analysis of the "Convention on the Rights of the Child" and "Law of the People's Republic of China on the Protection of Minors" (2012), selecting five dimensions (table 1), namely survival, health, protection, development and participation, this paper attempts to present and analyze the poverty situation of rural left-behind children, and makes policy recommendations based on the existing policies for the protection of left-behind children. The ages of 10-18 are a critical period for children to learn correct values and establish their outlook on life. In rural China, a large number of children cannot experience the love and caring of family life, so a comprehensive evaluation of the learning and living experiences of left-behind children of this age group is of great significance to the in-depth understanding of left-behind children's lives and spiritual world.

Table 1Analytical framework and its meaning

|

Dimension |

Meaning |

|

Survival |

Basic subsistence, including food, clothing, housing, etc. |

|

Health |

Mainly refers to health conditions, including health care, drinking water, sanitation, energy environment, etc. |

|

Protection |

Whether schools, families and society can provide a safe environment for the growth of children |

|

Development |

Children's intellectual development, mainly referring to the protection of the right to education; Child's ability development, including whether they have a healthy mental status, a positive and optimistic attitude towards life, a sound personality and good interpersonal relationships; Whether schools, families and society have provided a good environment for the development of children, including family harmony, parental care, etc. |

|

Participation |

Children's participation in family, cultural and social activities, including their own decisions on their daily life, study, making friends and hobbies. |

3.2 Sample Description

Data in this paper come from the child questionnaire of the "Investigation on the Multidimensional Poverty of Farmers in Contiguous Poor Areas with Special Difficulties" conducted by International Poverty Reduction Center in China (IPRCC) in 2013, covering six counties of Sichuan, Inner Mongolia, Guangxi and Gansu, namely: Du'an Yao Autonomous County (minority autonomous county) of Guangxi, Kangle County of Gansu, Yilong County of Sichuan, Helingeer County of Inner Mongolia, Tumote Left Banner of Inner Mongolia and Qinghe County of Inner Mongolia. Except for the three Inner Mongolian counties, the other three counties are noted as key counties for national poverty alleviation and development. Through a random sample selection, we organized questionnaires and team group interviews of the students of the village and town primary and secondary schools. In order to ensure the children correctly understand the questions, the research group mainly interviewed students above primary school grade four.

The survey collected a total of 2,003 questionnaires. Excluding those registered as urban residents and any children under tenor above 18, this paper obtained total of 1,839 valid samples, of which 883 are boys and 956 are girls.

Currently, the term "left-behind children" has several academic definitions. The focus of discussion is often dependent on when parents move to the city and how long the children are separated from their parents. This paper uses the more common definition of left-behind children: "Minors under 18 years of age whose parents or single parent moved from rural areas to other regions and left them in the countryside where they are registered and who cannot live together with their parents (Children's Department of the ACWF, 2011)". In addition, this paper limits its scope to children who have been separated from their parents for at least three months.

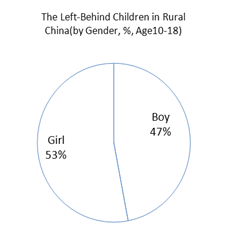

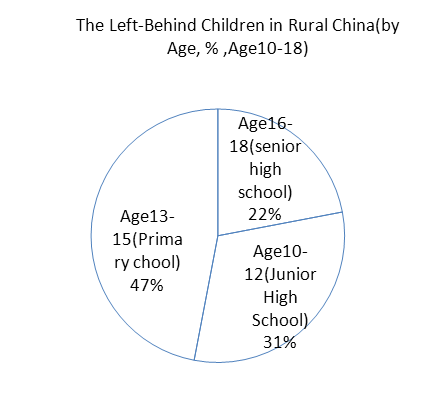

Based on the above definition, the 10-18-year-old left-behind children of rural households in the sample account for 49% of the total of this age group. Among the rural left-behind children of school age, the proportion of girls is slightly higher than that of boys (53:47). Children 10-12 years old (upper grades of primary school) account for 31%, children 13-15 (junior middle school students) account for 47% and children 16-18 (senior middle school students) account for 22%.Left-behind children separated from their parents for at least half a year account for 27% of the total.

Figure 1 Overview of rural children left behind (10-18 years old)

4. Multidimensional Poverty Situation of Children Left Behind in China

4.1 Survival

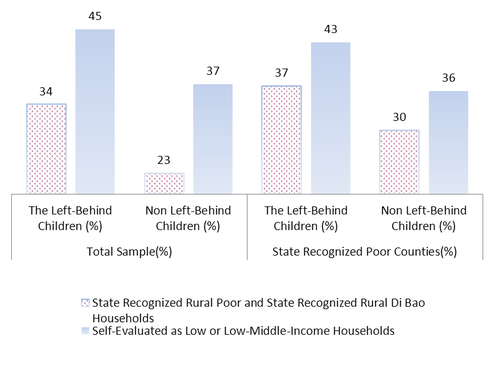

Left-behind children lag behind other children in many aspects, including household assets, food, housing and clothing, and they have to face many life difficulties independently. As for the living conditions of children left behind, for example, among the identified poor families and the families receiving subsistence allowances, families of left-behind children account for a higher proportion. Many scholars have questioned the standards for identification of poor families or households receiving subsistence allowance, but regardless, the survey results show that nearly half of the left-behind children believe their living standards are below the average or worse than those of other families, and that their families’ living standards are lower than those of non-left-behind children.

Figure 2 Family poverty situation of children left behind (10-18 years old)

The "China Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development Program (2011-2020)" clearly stipulates that the overall objective of China’s poverty alleviation and development program is to provide adequate food and clothing for the poor and protect their rights to compulsory education, basic medical care and housing by 2020. According to the survey results, left-behind children do lag behind other children in many of these aspects, including food, clothing, shelter, medical care and education.

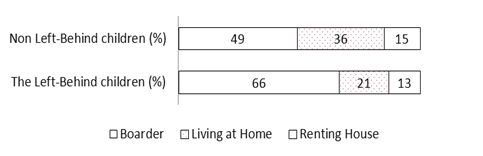

Left-behind children lag behind other children in housing and living conditions. They mainly live at school, at home or in rented houses. More than 2/3 of the left-behind children live at school. In the minority autonomous counties, according to the surveyed samples, the proportion of children left behind living at school is as high as81%. The children living at school also show a trend of being increasingly young. 56% of the left-behind children began to live at school during primary school (5-11 years old), among whom 19% begin to live at school at age ten (grade five of primary school). Most of the non-left-behind children, however, began to live at school at the age of 10-12. Living at school can be detrimental to the health and psychological development of the younger children (see Part 5 of this paper for detail). Of note, 57% of the left-behind children living at school are girls.

Figure 3 Living places of rural children (10-18 years old, %)

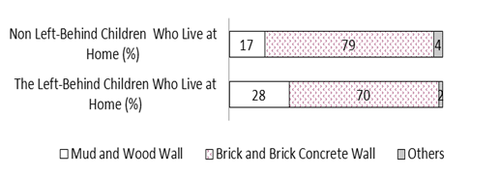

The second-largest group of rural children lives at home. To those left-behind children living at home, their living conditions are also significantly worse than those of the non-left-behind children (figure 4). In rural areas, for example, 28% of the 10-18-year-old left-behind children live in unsafe houses with mud or wood walls. Only 17% of the non-left-behind children live in such poor environments.

Figure 4 Home wall structure of rural families with children living at home (10-18 years old, %)

"No worries about clothing" as part of the development plan has not yet been fully realized for left-behind children. Among the surveyed, 18.09% of the left-behind children and 14.59% of non-left behind children said they do not have adequate clothing, especially in the minority autonomous counties, where 22.38% of the left-behind children and 15.95% of the non-left-behind said they do not have enough clothes. The result of the investigation on whether rural children have enough clothes to wear in winter shows the same trend.

4.2 Health

4.2.1 Overall health situation

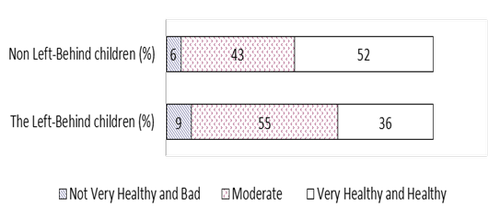

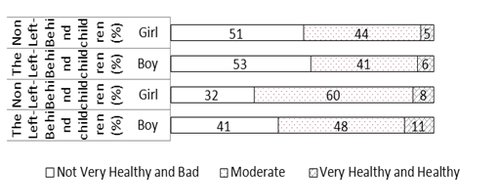

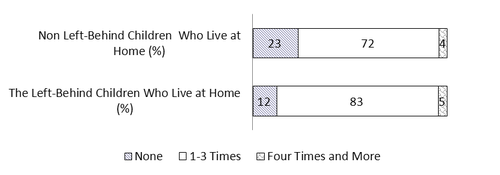

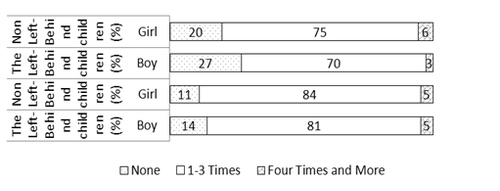

Left-behind children tend to be physically weaker than their counterparts. According to the survey, 9% of the left-behind children and 6% of the non-left-behind children felt their health was poor (Figure 5), and specifically for girls, the number of those who feel healthy was nearly 20% less than the non-left-behind girls (Figure 6). More than half of non-left-behind children believed they were in good physical condition, and more than half of children left behind thought they were in average physical condition (Figure 5). More than half of non-left-behind girls believed they were in good physical condition and 3/5 of the left-behind girls said their health was average(Figure 5-1).. Among those children who were ill in the past month, the proportion of left-behind children is 11% higher than that of the non-left-behind, and more than 4/5 of the left-behind children became ill one to three times (Figure 6). The proportions of left-behind boys and girls are both lower than that of the non-left-behind ones (Figure 6-1).

Figure 5Self-evaluation of the physical condition of rural children (10-18 years old, %)

Figure 5-1Self-evaluation of the physical condition of rural children (10-18 years old, gender-based, %)

Figure 6Rural children ill in the past month (10-18 years old, %)

Figure 6-1 Rural children ill in the past month (10-18 years old, gender-based, %)

4.2.2 Nutritional intake

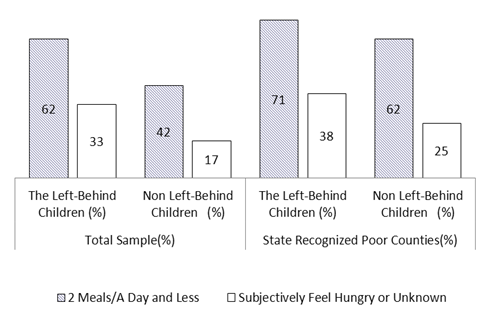

Compared to non-left-behind children, children left behind nearly all face the problem of inadequate nutrition intake, which is one of the root causes of their poor health. The proportion of left-behind children whose three meals a day cannot be guaranteed is obviously higher than that of non-left-behind children. Among the interviewees, 62% of the 10-18-year-old left-behind children have only two meals or even one meal a day, but only 42% for non-left-behind children,, a difference of 20%. The nutritional situation in the surveyed poor counties is even more serious. 71% of the left-behind children and 62% of the non-left-behind children only have one or two meals a day. The proportion of left-behind children among those who thought they did not have adequate food or were unsure is also higher than that of non-left-behind children (Figure 7).

Figure 7the situation of meals for rural children (10-18 years old)

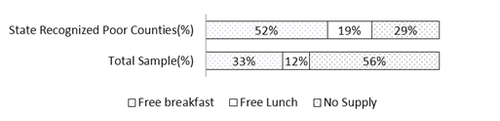

Column 1:Nutrition Improvement Program for Rural Compulsory Education

In order to address the poor physical health of children due to inadequate nutrition in poverty-stricken areas, China launched the "Nutrition Improvement Program for Rural Compulsory Education" in 2012. The government provides lunches in the pilot areas, including in impoverished regions, minority areas, border regions and former revolutionary base areas. Needed funds are allocated by the local government. The food to be supplied, especially snacks, should include meat, eggs, milk, vegetables and fruits (Ministry of Education, 2012). Currently, however, as the standard for a nutritious meal is 3 Yuan/meal, many local governments provide breakfast instead of lunch (Figure 8). The supply of nutritious meals in poor counties is better. More than half of the children have free breakfast and 1/5 of the children have access to free lunches (free breakfast and free lunch are not supplied simultaneously). More than half of the free lunches contain eggs, and 35% contain meat.

Figure 8 Situation of rural nutritious meals

In the evaluation of the nutritional lunch, more left-behind children said "the nutritious meals are not enough" or "free meals taste bad". More than 1/4 of the children left behind thought the nutritious meals were inadequate and 1/3 did not think the meals tasted good. The proportion of the non-left-behind children who are satisfied with the nutritious meals is obviously higher than that of the left-behind, with a ratio of72%: 66%. Nearly half of the children said that free nutritious meals are better now.

4.2.3 Nutrition balance

Another reason for poor physical health is nutritional imbalance. Many left-behind children are cared for by single parents, grandparents or themselves. Single parents must generally work harder. Due to long-term exhaustion, it is difficult for them to pay enough attention to their children’s daily meals; for those children who are looked after by their grandparents, the elderly usually have simple diets and spoil the children by giving in to the children’s pickiness; children who care for themselves do not realize the importance of a healthy diet as they have not developed complete cognitive ability, so they choose food according to their own preferences.

Case 1: Yuan Yuyin from Anhui Province left for work in the city when her children were only one and a half years old. Over the past six years, the children were looked after by their grandparents. She was full of guilt when she said: "My daughter only eats rice and drinks porridge, never eats vegetables, but occasionally eats some potatoes. The situation of my son is almost the same. He never eats vegetables, but his grandparents do not care. His grandfather prefers greasy food and the dishes are often salty…"

Case 2: Jin Xiaoqin from Dingxi of Gansu serves as a housekeeper in Beijing, leaving her daughter and son at home. Before coming to Beijing, she consciously cultivated her children's ability to cook for themselves. Once, she found out that her son went through a 2.5kgbucket of oil in one week! When asked the reason, her son said he poured oil directly in his bowl of noodles because it "tastes delicious".

4.2.4 Health behaviors

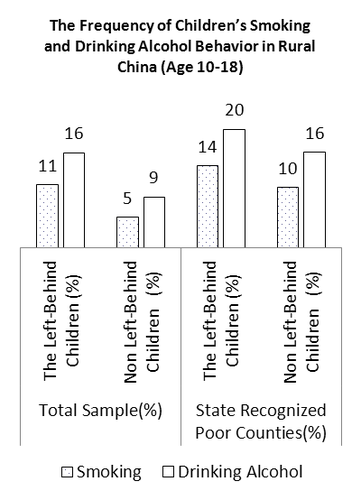

Due to lack of parental supervision, a large number of left-behind children have formed bad habits such as smoking and drinking. In general, among the rural children aged 10-18 with experience of smoking and drinking, the proportion of left-behind children is obviously higher than that of non-left-behind children, especially in poor areas. In rural areas, more children have experience in drinking than smoking. Especially in poor areas, nearly 1/5 of the left-behind children have drinking experience (Figure 9). It is probably because parents in rural areas usually allow children, especially boys, to drink when they gather together.

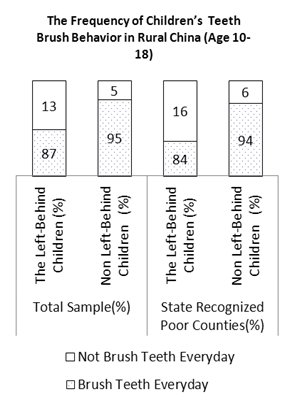

Health habits of children left behind are also worse than those of non-left-behind children, especially in impoverished areas. Among those surveyed, 13% of the left-behind children do not always brush their teeth daily, only 5% of non-left behind children report the same.

Figure 9Health behaviors of rural children

4.2.5 Long distance to see a doctor and medical insurance

In general, the difficulty of seeing a doctor in rural areas has shifted from “being too expensive” to “being too far”. In rural areas, only half of ill children can see a doctor within one kilometer of their homes and 11% of them must seek help five kilometers away. The situation in minority autonomous counties is worse. Only about 1/3 of ill children can visit a doctor within one kilometer and nearly 20% of them can only see a doctor five kilometers away. In addition, left-behind children’s participation in the rural cooperative medical system, medical insurance system or public health service is also lower than that of non-left-behind children. Only 70% of the left-behind children are covered by medical insurance, and84% of non-left behind children.

4.2.6 Sanitation

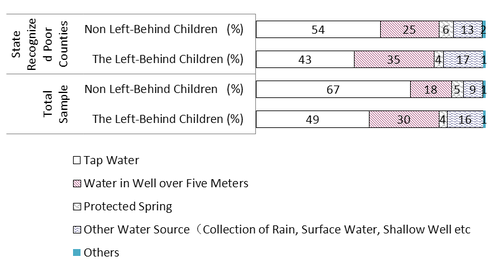

Poor living environments and poor sanitary conditions are also causes of the poor physical health of left-behind children in rural areas. Water is the source of life, but 17% of the left-behind children’s families have no access to safe drinking water (shallow wells of less than five meters deep and other unprotected water sources).Many single mothers or elderly people do not have the money or physical strength to improve their family environment and maintain a household. They continue to use older methods of fetching water. 30% of the left-behind children’s families in minority autonomous counties and 24% of the non-left-behind children’s families have no access to safe drinking water (Figure 10). In addition, for those children left home without running water, having to fetch water is also one of the reasons for their little spare time (See 4.4).

Figure 10 Situation of drinking water safety of rural families

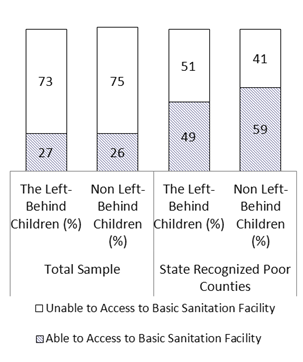

The sanitary conditions of left-behind children’s families are also poor. Shang Xiaoyuan and Wang Xiaolin (2012) consider indoor and outdoor flushing toilets and dry sanitary latrines as the minimum available sanitation facilities, and consider the use of chamber pots and dry latrines as no access to basic sanitation facilities. More than 70% of the surveyed rural households have no access to basic sanitation facilities (Figure 11).The circumstances of left-behind children’s families and non-left-behind children’s families are almost the same. Dry latrines are widely used. In the surveyed minority autonomous counties, however, more than half of the left-behind children do not have access to basic sanitation facilities, 10% more than the non-left-behind children.

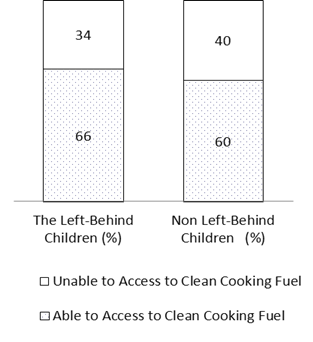

Since the burning of coal, firewood and animal dung are a threat to health, any family using the above resources for cooking or heating is considered to be experiencing “energy poverty”. In general, more than 3/5 of rural families live in energy poverty (Figure 12) due to their reliance on coal. There are more left-behind children’s families in energy poverty than non-left-behind children’s families. Such an environment seriously affects those left-behind children who need to do housework, especially girls.

Figure 11 Situation of rural health facilities (toilets) Figure12 Situation of rural household cooking fuel

4.3 Protection

4.3.1 Rural children's overall evaluation of "sense of security"

Generally speaking, schools and families are responsible for protecting children. Most children believe schools and families are safe, and more children believe families are safer than schools, but there are still subtle differences between the feelings of children left behind and those of non-left-behind children. More children left behind feel schools are safe and more non-left-behind children believe families are safe. Among those believing families are safe, the number of left-behind girls is slightly smaller than that of non-left-behind girls. Among those believing schools are safe, there are more left-behind girls than non-left-behind ones.

Schools and families should bear the primary responsibility for the protection of children. They are obliged to teach children to recognize danger and how to avoid being hurt. Especially at the elementary level, parents and teachers should teach children how to cross the road, escape an earthquake and avoid fire, for example. According to the survey (Table 2), however, only 77% of the rural children said they know what is dangerous, of whom the proportion of children left behind is lower than that of non-left-behind children and the proportion of boys is higher than that of girls.

The schools do relatively well protecting their students. 90% of the rural children aged 10-18 years agreed that "teachers will tell me how to stay safe and protect myself". The proportion of children left behind among these children, however, is 6% lower than that of non-left-behind children, and the proportion of girls left behind is lower than that of non-left-behind girls.

Children left behind need extra care from their teachers. 68% of children left behind believe teachers can help them solve the problems that cannot be solved by their families, and this proportion of non-left-behind children is the same. However, the number of girls left behind among these children is smaller than that of non-left-behind girls, indicating that children left behind do always not get the teachers' extra care at school.

Table 2 Sense of security of rural children (10-18 years old)

|

|

Left-behind children (%) |

Non-left-behind children (%) |

||||

|

Overall situation |

Proportion of girls who agree |

Proportion of boys who agree |

Overall situation |

Proportion of girls who agree |

Proportion of boys who agree |

|

|

Believe family is safe |

79 |

80 |

79 |

84 |

87 |

82 |

|

Believe school is safe |

71 |

70 |

71 |

67 |

67 |

67 |

|

Know what is dangerous |

77 |

74 |

79 |

80 |

79 |

80 |

|

Teachers will tell me how to stay safe and protect myself |

87 |

88 |

86 |

93 |

95 |

91 |

|

Teachers can help solve the problems that cannot be solved by my family |

68 |

64 |

72 |

68 |

69 |

68 |

4.3.2 Domestic violence or parental corporal punishment

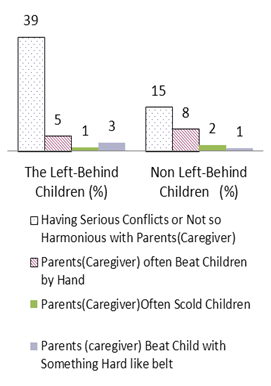

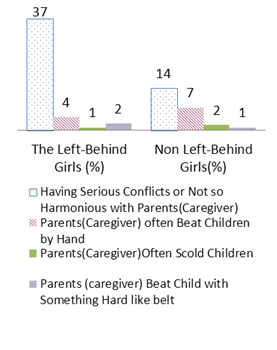

Many parents go to work in the city and leave their children to the care of their mothers or grandparents. The grandparents may even have to take care of the children of a few families at the same time. This family structure is extremely detrimental to children's growth. Single parents (mostly mothers) or grandparents often find it difficult to adequately look after their children. Nearly 40% of left-behind children live in "serious" disagreement with their guardians (Figure 13), 2.6 times that of non-left-behind children. The proportion of girls left behind among the children in "serious" disagreement with their guardians is higher than that of non-left-behind girls. Such an "unhappy" family atmosphere has a serious negative impact on the growth of young people.

In the left-behind children’s families, the parents are usually too busy or the grandparents are too old to physically punish children. In the families of non-left-behind children, however, punishing children is actually more frequent. When guardians disagree on child education, 3% of the left-behind children’s families often hit their children. In the families of non-left-behind children, however, this proportion is only 1%.

Figure 13 Rural domestic violence or corporal Figure 13-1 Girl victims of

punishment of children (10-18 years old domestic violence

4.3.3 School violence

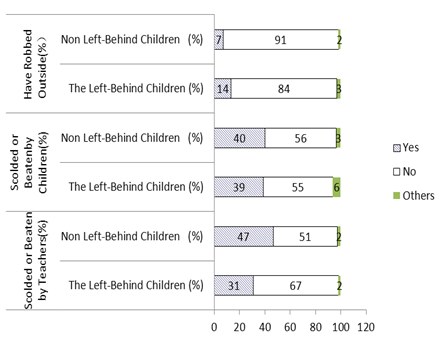

Article 29 of China's "Compulsory Education Law" provides that "teachers should respect students' personality and shall not discriminate against students, not conduct corporal punishment or disguised corporal punishment, or conduct any other behavior that insults the dignity of students, and may not violate students' legitimate rights and interests." In rural areas, however, the phenomenon of corporal punishment by teachers still exists. At school, the proportion of children left behind suffering corporal punishment is smaller than that of non-left-behind children. 30% of the children left behind and 47% of the non-left-behind children have received corporal punishment at school at least once (Figure 15).

School violence also includes abuse and conflict among students. Among the surveyed students, 39% of left-behind children and 40% of non-left-behind children have such experience. It is worth noting, though, that the rate of school as determined in this paper is about twice that of China Child Welfare Demonstration Area calculated by Shang Xiaoyuan and Wang Xiaolin (2012).

4.3.4 Violence against children in society

In rural areas, the prevalence of violence against children left behind is higher than that against non-left-behind children. In Shang Xiaoyuan and Wang Xiaolin’s survey (2012), 2.49% of the children of the surveyed county had been robbed outside school. Our survey results show, however, that 14% of the children left behind and 7% of the non-left-behind children were robbed outside school at least once (Figure 14), especially in impoverished regions, where the proportions reached 16% and 11%, respectively.

Figure 14 Situation of school violence and other violence in rural areas

(10-18 years old)

4.3.5 Other unsafety factors

Children left behind are usually more likely to suffer accidents due to lack of care or lack of relevant knowledge when they are not well looked after or when their parents are too busy to take care of them. Traffic accidents and drowning are two major causes of unintentional injuries resulting in death for Chinese children (Shang Xiaoyuan, Wang Xiaolin, 2012). Upon investigation, many rural parents admitted that they often asked their children to play alone in the street or to swim in the river, especially when they were too busy. The latest media reports on frequent such accidents among children left behind have attracted the notice of schools and society.

4.4 Development

Education is a basic right for children aged 10-18 years. At present, China promotes nine-year compulsory education. Based on research results, however, the most significant problem in the rural areas is how to improve the quality of education and ensure that children can spend time and effort on learning. This is particularly important for children left behind.

4.4.1 Availability of educational resources (distance to school, tuition, reference books)

(1) Distance to school

Rural children’s school environment and access to educational resources is not ideal. After implementing town mergers, the government integrated village-run primary schools in order to integrate educational resources. This has optimized the distribution of schools and teachers, but it has become harder for children in remote rural areas to go to school. Most of the children left behind tend to live far away from school, especially in minority areas. Among the surveyed students, 44% of the children left behind and 32% of the non-left-behind children’s families live more than five kilometers, or 40 minutes’ walk away from school. The situation in minority autonomous counties is more serious. 64% of the children left behind and 44% of the non-left-behind children’s families live more than five kilometers away from the school. As a result, 81% of the children left behind and 63% of the non-left-behind children must live at school.

(2) Reference books

Rural children’s access to study resources is also poor. For example, China began to provide the Xinhua dictionary for free to rural students ingrades1-9 since winter 2013, though not all rural students have received them. The proportion of children left behind who were provided free dictionaries is obviously lower than that of non-left-behind children, and the ratio between the two is 65%:81%. Positive changes have taken place in minority autonomous counties; within creasing support from the government, among the students of grades4-9 in these regions, 80% of the children left behind and 93% of the non-left-behind children each have a dictionary, but the left-behind children are still in a disadvantaged position.

(3) Tuition

Although there exists the "two exemptions and one subsidy" policy, 35% of left-behind children and 31% of non-left-behind children are still concerned over tuition. In the surveyed minority autonomous counties, nearly half (47%) of the children left behind worry about school fees, but the proportion of the non-left-behind is only 37%.

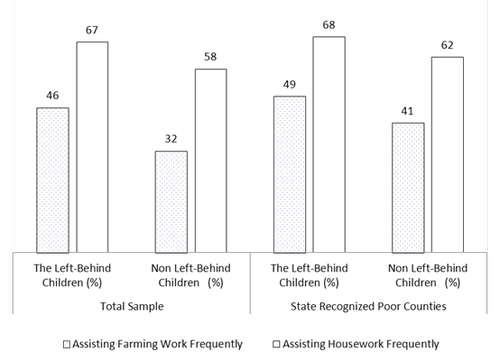

4.4.2 Free time (whether children need to do extra farm work and housework)

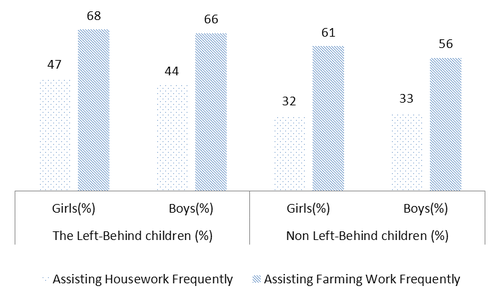

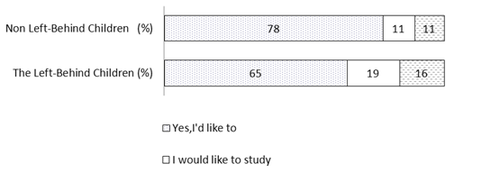

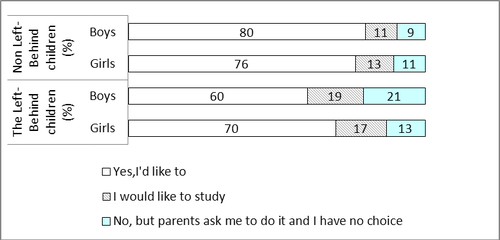

As single mothers and elderly grandparents’ labor capacity is limited, children left behind usually need to do extra housework or farm work, especially in minority areas. Among the surveyed, 46% of the left-behind children often help their parents do farm work and only 1/3 of non-left-behind children need to do such work. More than half of rural children often need to help their parents with housework, of whom the proportion of left-behind children is higher than that of non-left-behind ones (Figure 15). Of the children who often need to do housework or farm work, the proportions of left-behind boys and girls are both higher than that of non-left-behind boys and girls (Figure 15-1).

Most children are willing to help their parents do housework, of whom the proportion of children left behind, however, is significantly lower than that of non-left-behind children (Figure 16). This is mainly because, compared with non-left-behind children, children left behind need to participate in more onerous agricultural and domestic labor. When asked "what do your guardians force you to do?", the proportion of non-left-behind children who selected the answer "nothing" is significantly higher than that of children left behind, and left-behind children usually indicate heavy agricultural labor such as mowing, farm work, taking animals to pasture, chicken slaughter and fetching water. The answers of non-left-behind children, however, are mainly related to life, light agricultural labor, family or teachers, such as cutting hair, taking care of younger siblings and washing dishes.

Figure 15 10-18-year-old rural children's participation in farm work and housework (overall situation)

Figure 15-1 10-18-year-old rural children's participation in farm work and housework (gender-based)

Figure 16 10-18-year-old rural children's voluntary participation in farm work and housework (overall situation)

Figure 16-1 10-18-year-old rural children's voluntary participation in farm work and housework (gender-based)

Most rural children understand that their guardians need help and are willing to help with farm work and household chores, but fewer left-behind children are willing compared to non-left-behind children and fewer left-behind girls are willing to help their guardians compared to non-left-behind girls (Figure 16 and Figure 16-1). Among the children left behind unwilling to work, 19% of children left behind said: "I do not want to work; I want to go to school", 16%said" I’m not willing, but I do the work assigned to me".

4.4.3 Enthusiasm for learning (attitude for studying)

As for enthusiasm for learning, there is little difference between children left behind and non-left-behind children. 0.7% of the left-behind children and 0.9% of the non-left-behind children expressed their unwillingness to study. According to the survey results, the proportion of children tired of studying in minority autonomous counties is relatively high, but the proportion of non-left-behind children among them is higher than that of children left behind. This shows that in these economically lagging areas, the experience of left-behind children’s parents as migrant workers has impacted the educational philosophy of the entire family; they believe that knowledge can change their destiny and they cannot escape poverty unless they study hard.

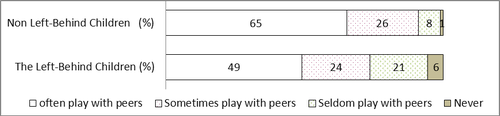

4.4.4 Communication skills (willingness to interact with others)

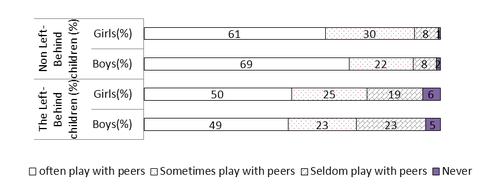

Lack of interactionism one of the causes of psychological issues among children left behind. Some of them never or seldom play with others. Among the surveyed children, less than half of left-behind children said they often play with partners and 6% of the children left behind never play with others. On the contrary, 65% of the non-left-behind children often play with their peers and only 1% of non-left-behind children never play with peers. Left-behind girls are particularly reluctant to interact with people (Figure 17-1). 6% of girls left behind never play with others but only 1% of non-left-behind girls.

Figure 17Rural children's interaction with classmates (10-18 years old)

Figure 17-1 Rural children's interaction with classmates

(gender-based, 10-18 years old)

4.4.5 Family harmony (mother's divorce rate)

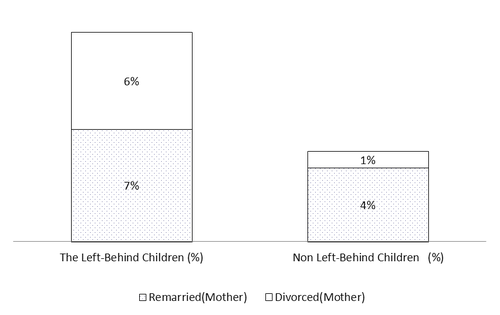

Mothers are very important to childhood development. When asked "what do you most want to say to your mother", 1/5 of children left behind expressed thanks for their mothers’ hard work, 1/5 expressed their love for their mothers, nearly 1/3 said their mothers worked hard and nearly 1/10 said they missed their mothers and hope for them to return. As left-behind children are separated from their parents for a long time, many of their families have been broken apart, which has an extremely negative impact on the growth of children. As for mothers’ remarriage and divorce (Figure 18), the proportion of remarried or divorced mothers of children left behind is significantly higher than that of non-left-behind children. A child wrote: "Mom, I hope you can be a goodwife and mother to another family". This short sentence not only reveals that the mother did not provide enough care for her child due to busy work or household chores, but also shows the significance of family harmony to children’s growth.

Figure 18Proportion of remarried and divorced mothers of rural children

(10-18 years old)

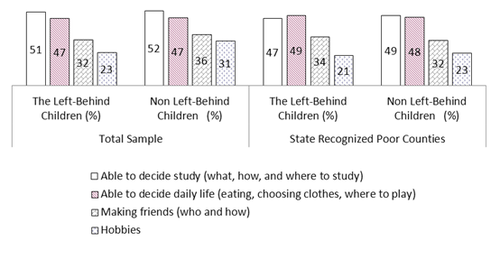

4.5 Participation

Children’s right of participation refers to a child’s right to participate in family, cultural and social life (Shang Xiaoyuan, Wang Xiaolin, 2012). This paper conducts a comprehensive comparison of the participatory rights of children left behind and non-left-behind children in daily life, learning, making friends, and hobbies. On the whole (Figure 19), more than half of the 10-18-year-old children in rural areas can independently determine their studies (what to learn, how to learn and which school to attend), no significant difference between the situations of children left behind and the non-left-behind children, followed by daily life, making friends and hobbies. Only 23% of left-behind children and 31% of non-left-behind children can choose their own hobbies. There is little difference between the situations of left-behind children and non-left-behind children in determining their studies and daily life. For making friends and choosing hobbies, however, the situation of children left behind is worse than that of non-left-behind children.

Figure 19Participatory rights of children in rural areas (10-18 years old)

4.6 Summary

Many people believe that the material conditions of rural children left behind should be better than that of non-left-behind children because their parents are away working. On the contrary, according to the survey results, left-behind children are at a disadvantage in many aspects, including family assets, food, housing and clothing compared to non-left-behind children. 1/3 of rural left-behind children (10-18 years old) are from poor families or families covered by the low-income subsidies. 2/3 of the left-behind children live at school and 56% of the children left behind began to live at school at the elementary level (5-11 years old). Among these children, there are more girls than boys.

Health and medical care are fundamental children’s rights (Shang Xiaoyuan, Wang Xiaolin, 2012). Due to lack of care, many left-behind children are in poor physical health. Children are at a critical stage of growth, but the vast majority of children left behind lack adequate and timely nutrition, resulting in poor development. Left-behind children living at home eat poorly due to lack of care, poor self-management and poor family conditions. For the left-behind children living at school, the school cannot provide enough detailed care to ensure children each nutritional standard. Constraints of rural children's health also include the long distance needed to visit a doctor and the narrow coverage of medical insurance, especially for children left behind.

Schools and families do protect children. But the proportion of rural children aged 10-18 years who feel that school is safe is lower than those who feel family is safe. Of the rural children who felt that family is safe, the proportion of left-behind children is lower than that of non-left-behind children, and the proportion of left-behind girls is lower than that of non-left-behind girls. Teachers do not show extra concern for the safety of children left behind. The proportion of the guardians’ "hitting children with a hard object" in left-behind children’s families is higher than that in non-left-behind children’s families. Left-behind children also face many problems in other security aspects. For example, more children left behind are robbed and these children often play independently in dangerous places.

Compared with other children, left-behind children are not so tired of studying, but have fewer development opportunities and are in a disadvantageous position in terms of access to educational resources and free time. The children left behind can have serious psychological problems and are less willing to play with other children, especially left-behind girls. Family discord increases growing pains of children left behind who are already fragile.

10-18-year-old rural children’s participation rights in order of time are study, daily life, making friends and hobbies. Left-behind children are the same situation in determining studies and daily life as the non-left-behind ones, but they are in a disadvantageous position in making friends and enjoying hobbies.

5. Policies and practice for left-behind children

5.1 Policies

5.1.1 Central policy

With increasing mobility of people in the process of urbanization, the problem of migrant children's education has captured the government’s attention resulting in related policies. Local governments of the areas where migrant workers work are responsible for the education of migrant children, and the governments of the migrant workers’ home villages are responsible for the education of left-behind children. In 2006, the Special Work Group on Left-behind Children comprising those from 13 departments including the All-China Women's Federation and the Ministry of Education was established. This formally established a working mechanism for coordination of issues concerning the education, health, household management, social security and financial support of rural left-behind children. In 2007, for the first time, China carried out a nationwide survey on rural left-behind children, and the State Department Office of Affairs of Migrant Workers included the situation of rural left-behind children into their prospective study of migrant workers’ issues. The Special Work Group on Left-behind Children carried out two thorough, successive large-scale nationwide studies in 2007 and 2012, and released the results reports respectively in 2011 and 2013, which provided a scientific basis for government decision-making. T Special Work Group on Left-behind Children used its strength in coordination to policy documents showing the respective responsibilities of the member units such as the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health, and clarified their work priorities. Over the past decade, compared to other areas, the left-behind children's education-related policies are quite prominent, and the policies developed to solve the education problem of left-behind children are becoming better and increasingly specific.

5.1.2 Local policy

More than 20 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions in China have written the protection of rural left-behind children’s rights and interests into the provincial measures for implementation of the "Compulsory Education Law" and "Law of the People's Republic of China on the Protection of Minors.” Many such policy documents have also been formulated by local departments of various levels, such as the opinions on relevant work and the implementation methods covering education, child protection and psychological care. According to statistics, from 2004 to 2008, local women's federations participated in the formulation of 542 provincial and municipal documents to address the problems of rural left-behind children. At present, policy implementation varies among regions. Some provinces and municipalities have not yet developed specific policies to protect left-behind children and the management of left-behind children is conducted under the general child protection policy. Some provinces and municipalities have developed specific policies related to the issues of left-behind children, with clear objectives and specific tasks, but some provinces and municipalities have only formulated the regulations. Many innovations have been made in the management of left-behind children in various regions, and some policies have been developed to encourage left-behind children to migrate with their parents.

5.2 Practice

5.2.1 Rural boarding schools

The "Decision on the Reform and Development of Basic Education" issued by the State Council on May 29, 2001 indicates that China should "adjust rural compulsory education schools based on local conditions". Since then, many rural primary and secondary schools have been merged. Subsequently, the Ministry of Education and other departments issued the "‘Two Basics Program in Western China (2004-2007)" (2004), the “Construction Program for Rural Boarding Schools in Western Regions" (2004), the "Several Opinions on Further Promotion of the Construction of Rural Boarding Schools" (2005), the "Notice of the Ministry of Education on the Distribution Adjustment of Rural Secondary and Primary Schools" (2006), the "Interim Measures on School Management of the Construction Program for Rural Boarding Schools in Western Regions" (2006) and the "Notice on Good Results of Rural Boarding School Building in the Counties ‘Popularizing Nine-year Compulsory Education’" (2008),etc., which clarified the objectives, tasks and implementation plan of the rural boarding school building project. The state has gradually strengthened the use of special funds for rural boarding school building and the relevant construction projects, and increased subsidies and relief efforts for boarding students from needy families.

With an increasing number of left-behind children, rural boarding school building has been gradually included in the list of important measures to show concern and care for left-behind children. In July 2010, "China's National Plan for Medium- and Long-term Education Reform and Development (2010-2020)" was promulgated. The "Program" affirmed the significance of rural boarding schools in addressing problems of left-behind children and promoting the development of education in minority areas (Qi Jian, Ye Qingna, 2013), and specifically proposed to "accelerate the construction of boarding schools in rural areas, giving priority to meet the accommodation needs of children left behind." In January 2013, five departments including the Ministry of Education jointly issued the "Opinions on Increasing Care and Strengthening the Education of Rural Left-behind Children at the Stage of Compulsory Education", which focuses on effectively improving the learning conditions of left-behind children by prioritizing access to boarding school, good meals and convenience for the left-behind children in impoverished areas .

Boarding schools have eased the problem of the lack of care for children left behind and have provided basic living care, supervision and guidance on learning, as well as opportunities for interaction and play with peer groups. In practice, however, there are still many problems. For example, student dormitories are crowded, teachers are too busy to work on emotional communication with students, school safety management is relatively poor and the meals are inadequate, all of which affect the healthy growth of children in rural areas.

5.2.2 Psychological counseling room

Left-behind children usually have some psychological difficulties. Supported by the government, schools and NGOs, some primary and secondary schools in rural areas have begun to set up psychological counseling rooms for left-behind children. Currently, these activities nationwide include group counseling, individual conversations, counseling by phone and letters as well as seminars, covering education on feeling grateful, morals, safety, and the environment. The counselors are mainly school teachers, university student volunteers and social volunteers.

School psychological counseling rooms provide an effective way to prevent and alleviate a variety of psychological problems of left-behind children. Still, difficulties remain. For example, psychological counseling is not widely accepted, and children themselves are often not willing to receive psychological counseling service, for fear of receiving a label as a "problem children" and there are not enough human resources for psychological counseling. "Currently, the counselors are usually part-time teachers with a number of jobs, who do not have professional theoretical and practical knowledge on psychological consulting. In addition, their heavy burden of teaching work will also surely have an impact on their input of time and effort for counseling. “(Ye Jingzhong, etc., 2008)

5.2.3 School for Parents and Guardians

The "Guiding Opinions on the Work of Parent Schools Nationwide (Trial)" issued by the All-China Women’s Federation and the Ministry of Education in 1998 explained that "Since the 1980s, China’s family education work has witnessed rapid development. Parent schools are one of the effective methods, and have been set up throughout the country. At present, there are a few hundred thousand parent schools nationwide." In 2004, the based on the above Opinion, the All-China Women’s Federation and the Ministry of Education jointly issued the "Guiding Opinions on the Work of Parent Schools Nationwide", which further clarified the nature and tasks of parent schools, provided regulations on guidance and management, organization and leadership, assessment and inspection. In 2006, the All-China Women’s Federation set up 1000 demonstration parent schools for migrant and left-behind children. Based on local conditions, a number of guidance agencies for the work related to rural left-behind children have been set up, including the "Parent School for Left-behind Children" in Sichuan Province, the "Grandparent Training Class for Left-behind Children" in Jiangsu Province, the "Four Elderly Parent School" and the "Family Education Guiding Center for Left-behind Children" of Henan Province.

The activities organized by "parent schools" are varied, including collective guidance and learning through parent meetings, winter meetings for parents of left-behind children, and class seminars (Huang Ying, Ye Jingzhong, 2007), etc. The training covers all aspects of family education, and mental health education has been included specifically for children left behind. However, "parent schools" ultimately face limitations, for example, the participation rate of long-term migrant parents is low, temporary guardians (such as grandparents and relatives) are not always enthusiastic and have high requirements for the school’s teaching resources.

5.2.4 Surrogate parents

There are two main forms of surrogate parenting. The first is a government-led, public participation social assistance measure. Mingyu town of Nanchuan City, Chongqing is one of regions with the longest history of implementing the surrogate parent system and has conducted the most in-depth work in the field. It organizes cadres to establish relationships with left-behind children on a one-to-one basis and become their surrogate parents. The second types are paid "professional surrogate parents", which is a new occupation created to meet the market demand, combining the traditional home economics and tutoring functions. People in this occupation are usually laid-off and retired teachers or traditional domestic workers. Professional surrogate parents sign contracts with the parents of left-behind children and promise to take care of the children’s lives and guide their learning, while the parents provide timely compensation.

Compared with boarding schools, surrogate parents do better in taking care of children and meet the left-behind children’ s emotional needs to some extent. In addition, because of their relatively high education and personal standards (most of them are cadres and teachers) compared to grandparents, surrogate parents have an obvious advantage in education. Limitations do exist: first, "surrogate parents" are not legal "temporary guardians”; their legal status is not certain and their responsibilities are unclear; second, the "surrogate parents’ behaviors" are based on individual personal feelings and ethical considerations; third, surrogate parents have find themselves in an awkward position: if they are too strict with the children, they are afraid the children will be unhappy; if they are not strict enough, however, they may be considered as neglecting their duty; fourth, professional surrogate parenting is not a traditional occupation and therefore lacks a supervision system. Finally, as professional surrogate parents expect payment for their services, it is hard to promote the practice in rural areas, especially in impoverished rural areas.

5.2.5 Community-based family activity rooms

Community-based family activity rooms are public areas for children to study, play and exercise provided by the rural community. It is designed to mobilize rural communities to show care for local left-behind children (Zhang Keyun, Ye Jingzhong, 2010). The activity room is usually equipped with books, TV sets, telephones and computers. In some areas they are called “Left-behind Children’s Club" or " Left-behind Children’s Home". Initiated and organized by women’s federations at all levels, the activity rooms are supported by local governments, village committees and schools. To avoid duplication, family activity rooms are usually set up based on existing township cultural stations and village cultural activity rooms under the responsibility and management of specific persons. Relevant management, supervision and assessment systems have been established. The activities mainly include recreational and sports activities, education, training and care activities for children left behind, such as family video phone calls, and holiday greetings. Currently though, family activity rooms still need funding and supervision, and struggle in rural areas, especially in impoverished regions.

5.2.6 Host families

In 2007, seven units including the Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee and the All-China Women's Federation jointly issued the "Notice on the Implementation of Central Directives and Caring for Rural Left-behind Children", which proposed to "speed up the construction of care centers for left-behind children ". While developing policies to care about left-behind children, the governments of many regions also took it as an important task to establish a mechanism for trusted care of left-behind children.

The families entrusted to take care of left-behind children fall into two categories, for-profit and non-profit. Such host families do better in looking after children than boarding schools and provide more careful supervision than family activity rooms, but there are similar limitations. For example, host families pay more attention to management than education, and living collectively with many others may lead to formation of bad habits. In addition, because of the lack of supervision mechanism, there are certain risks to engaging private hosting families. Without "official status", private hosting families have little government support.

5.2.7 Family phone calls

The recent family phone call initiative is advocated by government and is participated in by public and private enterprises. Free telephones or pre-paid phone cards are provided in schools, homes, or community areas where there are left-behind children, so children can communicate with their absent parents.

6. Policy recommendations

Left-behind children are special, but also the same as other children-- they should also be with their parents as other children in the world. The state, therefore, should introduce relevant policies as soon as possible and encourage local governments to make policy innovations based on local conditions to allow left-behind children to move with their parents. At present, under the current household registration system and relevant restrictive policies, local governments should strengthen the care and protection of communities and schools for children and reduce the negative impact of "being left-behind" on children.

6.1 The state should significantly improve the environment for the growth of left-behind children, focusing on solving outstanding contradictions

The growth environment for children left behind is challenged by difficulties both within schools and the children’s families. While intervening in these issues, the government should take step-by-step measures to clarify the most pressing concerns. As slow progress has been made in the improvement of families’ physical conditions, the government should significantly improve the school environment to solve these outstanding problems restricting child development. In particular, with the increase in the number of younger students living at school, the government should increase subsidies for these children and continue to provide free nutritious meals, especially in impoverished regions and minority areas. We should use national financial resources to increase left-behind children’s access to dictionaries and other resources for learning and living. Meanwhile, the state should strengthen the collaboration of ministries, introduce preferential policies on child welfare and protection for left-behind children, and encourage local governments to implement pilot programs and make innovations.

6.2 Encourage the public to help left-behind children and create an atmosphere for the whole society to care of children left behind

Children left behind are a special group. They require the love and kindness. Meanwhile, these children are also ordinary children--they also have the right to play and study as other children in the world. The government should encourage NGOs to participate in activities promoting care of left-behind children, develop their confidence in society, school and family and help them establish a more positive and optimistic outlook on life.

6.3 Strengthen schools' management and care of children left behind

For students, the school is an important base for them to grow, where they learn knowledge and values. Schools should pay particular attention to the management of children left behind. Schools should be fair to all so that each left-behind child left will enjoy the same rights as non-left-behind children. Many left-behind children are do not do well in school, but schools must not give up on them and leave them to their own devices Schools should pay special attention to the life skills of children left behind and increase psychological intervention so that these children will grow up open-minded, and accept their classmates and teachers, and be willing to interact with others.

6.4 Strengthen community management to make up for the lack of family for children left behind

Family is essential for children's growth. To left-behind children, however, the lack of home management and care has increased their vulnerability. The increasing frequency of accidents involving left-behind children in recent years means that schools and families should pay greater attention to the importance of enhancing the safety awareness of children. Communities should also assume the responsibility of child management, especially for left-behind children living alone. The state should create conditions to conduct centralized management of these children and encourage relevant collective organizations and grassroots organizations to participate in order to promote the healthy development of children left behind.

References:

1. Amartya • Sen, Why Are We Particularly Worried about Child Development? , 2012.

2. Analysis on the Case of En Yang, Marketization of Left-behind Child Care, People's network, (Http://unn.people.com.cn/GB/14748/5809696.html), June 1, 2007.

3. Anhui Telecom launched the family love program for left-behind children and installed 20,000 free family telephone sets, Feixiang Network (http://www.cctime.com/html/2011-5-25/20115251716541107.htm), May 25, 2011.

4. Answers of Five departments including the Ministry of Education on relevant questions on care and education of rural left-behind children at the stage of compulsory education, website of China's Government (Http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2013-01/10/content_2309058.htm), Jan. 10, 2013

5. Children's Department of the ACWF, Survey Report on the Situation of Rural Left-behind and Migrant Children, 2011: Social Sciences Academic Press.

6. China will set up 1000 demonstrative parent schools for left-behind children of migrant workers. Sina (http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2006-05-28 /13459049240s.shtml), May 28, 2006.

7. Comrade Deng Li's Speech on the Seminar of Love for Rural Left-behind Children convened by the labor unions of some provincial (municipal) education departments, Website of Ministry of Education on Care for the Next Generation(http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_2536/200910/53291.html), September 22, 2009.

8. Cui Ping, Sun Hua,"Left-behind children need more love", People's Public Security, 1997 (11): P38-39.

9. Duan Chengrong, Yang Ge, Research on the Situation of Left-behind Children in Rural China, Population Research, 2008 (03): P15-25.

10. Editor in chief: Ye Jingzhong, (America) James • Murray, Concerns about Children Left Behind: Impact of Migrant Work in Central and Western Areas on Left-behind Children in China, 2005: Social Sciences Academic Press.

11. Henan set up "four old" parent schools to provide qualified guardians for left-behind children. China Education News Network (http://www.jyb.cn/xwzx/gnjy/gdcz/t20070103_58313.htm), Jan. 3, 2007.

12. Huang Ying, Ye Jingzhong, Role of Village-level Community in Rural Basic Education - Investigation and Reflection Based on Support Activities for Left-behind Children, Jiangxi Education and Research, 2007 (09): P101-103

13. Huang Ying, Ye Jingzhong, Study of the Role of Parent School in the Education of Left-behind Children -Based on An Investigation into the Parent School of Q County Rural Primary and Secondary School in Sichuan, Primary and Secondary School Management, 2007 (09): P54-56.

14. Journal of China Agricultural University (Social Science Edition), 2009 (02): P5-17.

15. Liu Minghua, etc., Research Report on Education of Rural Left-behind Children. Journal of Southwest University (Social Science), 2008 (02): P105-112

16. Ma Yajing and Jin Xiaoli, Comparative Study on the Mental Health of Rural Left-behind Children among Senior Students of Boarding and Non-boarding Schools - Based on A Town of Huaibei City, Social Work (second half), 2010 (11): P28-30.

17. Mei Jian, Lin Jian, Surrogate Parent System: Government Looks for "Parents" for Left-behind Children, Primary and Secnodary School Management, 2007 (04): P9-10.

18. Pan Lu, Ye Jingzhong, Research on Rural Left-behind Children,

19. Qi Jian, Ye Qingnuo, Study on Boarding School Policies in Rural China - Based on the Case of Rural Boarding School Policy Since 2001, Hunan Social Sciences, 2013 (02): P248-251.

20. Wang Xiaolin, Shang Xiaoyuan, etc, Frontier of Chinese Child Welfare. 2012: Social Sciences Academic Press: Chapters 1-2.

21. Wen Tiejun: To Address the Problem of Rural Left-behind Children At Three Levels, Henan Education, 2006 (05): P10-11.

22. Yao Jinzhong, Ju Donghong, Three-dimensional Empowerment: Construction of Social Support Network for Rural Left-behind Children, Research on Contemporary Youth, 2012 (12): P25-30.

23. Ye Jingzhong, etc, Research on Issues Related to Left-behind Children, Agricultural Economy, 2005 (10): P75-80, P82.

24. Ye Jingzhong, Pan Lu, A Different Kind of Childhood: Children Left Behind in Rural China, 2008: Social Sciences Academic Press.

25. Ye Jingzhong, Pan Lu, Research on the Emotional World of Primary Students of Rural Boarding Schools, Educational Science Research, 2007 (09): P29-31

26. Ye Jingzhong, Urban-rural Integration for Care About "Left-behind Children" in Rural Labor Transfer, Journal of Shanghai Technical College of Urban Management , 2008 (02): P35-39.

27. Ye Jingzhong, Wang Yihuan, Situation and Characteristics of the Custody of Children Left Behind, Population Studies, 2006 (03): P55-59.

28. Ye Jingzhong, Yang Zhao, Care for Children Left Behind - Actions and Countermeasures. 2008: Social Sciences Academic Press.

29. Yi Zhang, "Left-behind Children", Lookout Newsweek, 1994 (45): P37.

30. Zhang Keyun, Ye Jingzhong, Evaluation of Interventions on Left-behind Children from the Perspective of Social Support, Youth Studies, 2010 (02): P81-87.

31. 58 million left-behind children share 6500 hosting centers. ACWF News (http://acwf.people.com.cn/GB/99058/8266792.html), Oct 31, 2008.

Appendix: Central government's "left-behind children" -related policies and work arrangements

|

Time |

Responsible department |

Policy / work arrangements |

Content |

Type |

|

Feb 26, 2004 |

State Council |

Several Opinions on Further Strengthening and Improving Ideological and Moral Construction of Minors |