2014-The 8th ASEAN-China Forum on Social Development and Poverty Reduction4

Influence Factor Analysis: Based on Rural Survey Data in Hubei Province, Chinese Rural Economy,

(09): 68-77, 2011.

Huang, Z.: "Three Goes" Policy: Response, Performance and Comparison: Based on 1942

Households in 68 Villages in 20 Provinces (Autonomous Regions and Municipalities) Nationwide,

Chinese Rural Economy, (09): 60-67, 2011.

Ma, Z., Meng, J. and Han, Y.: Reflection on Local Government Land Conversion Subsidy Policy,

Public Finance Research, (03): 10-14, 2011.

Liu, X.: China New Rural Social Pension Insurance System and Pilot Analysis, Issues in Agricultural

Economy, (04): 55-61, 2011.

Feng, F., Du, Y. and Gao, M.: Investigation on Present China Rural Consumption Subsidy Policy

Efficiency and Benefit: Taking Xiaxiang Product Markets in Hefei Suburbs as Example, Issues in

Agricultural Economy, (06): 43-46, 2011.

Qin, X. and Zheng, Z.: New Rural Cooperative Medical Care's Effects on Rural Labor Migration:

Based on National Panel Data Analysis, Chinese Rural Economy, (10): 52-63, 2011.

Xu, L. and Lv, B.: The Operation Situation of NRCMS, the Satisfaction Situation of Participant

Farmers and its Factors: Taking Nanjing Suburbs as Example, China Rural Survey, (04): 63-73, 2010.

Wang, X.: Compulsory Education “Two Exemptions and One Subsidy” Policy’s Inhibition Effect on

Farmers’ Children Dropping out of School: Evidence from 24 Schools in 4 Counties(Banners) in 4

Provinces (Autonomous Regions), Economist, (04): 52-59, 2009.

Wu, Y.: An Empirical Analysis of New Rural Social Pension Participation Behavior: Viewing from

Social Capital in Village Domain, Chinese Rural Economy, (10): 64-76, 2011.

Yuan, S., Wu, J., Dong, J. and Zheng, B.: Exploration about Direct Subsidy's Effect on Farmers'

Income, Price: Theory & Practice, (05): 32-33, 2008.

Chen, D.: Problems and Countermeasure Studies on China Direct Subsidy to Farmers, Rural

Economy, (01): 8-10, 2005.

Qi, L.: A Study on the Anti-poverty, Income increasing and Re-distributional Effects of New

Cooperative Medical System, The Journal of Quantitative & Technical Economics, (08): 35-52, 2011.

World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work for Poor People, World Bank Publications,

2004.

Gupta, A. P.: Who Benefits from Central Government Expenditures? Economic and Political Weekly,

12(6/8): 267-286, 1977.

Peters, D. H., Yazbeck, A. S., R., S. R., Ramana, G. N. V., Lant, P. H. and Wagstaff, A.: Better Health

Systems for India's Poor: Findings, Analysis, and Options, World Bank Publications, 2002.

Devarajan, S. and Shah, S.: Making Services Work for India’s Poor, Economic and Political Weekly,

39(9): 907-919, 2004.

97

Jha, R., Bhattacharyya, S., Gaiha, R. and Shankar, S.: “Capture” of Anti-poverty programs: An

Analysis of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Program in India, Journal of Asian

Economics, 20(4): 456-464, 2009.

Park, A. and Wang, S.: Community-based Development and Poverty Alleviation: An Evaluation of

China's Poor Village Investment Program, CEPR Discussion Papers, DP7856, 2010.

Evaluation Report on the Implementation Effect of "Rural Poverty Alleviation Development Outline

(2001-2010)", The State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development of

China, 2010.

CHAPTER 6 CHINA-ASEAN COOPERATION IN DEVELOPMENT

ASSISTANCE

WANG Luo

Director Institute of International Development Cooperation

Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation

Ministry of Commerce, P. R. China

China-ASEAN development cooperation began in 1950. Since it provided assistance to North Korea and supported Vietnam to fight against the French colonialists, China has successively conducted development aid cooperation with Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. Over the past six decades, foreign aid has always been an integral part of the development of China's political and economic relations with foreign countries and an important part of China's mission to fulfill its internationalist obligations. With the changes in the domestic and international situations and China's domestic political and economic environment, China's development assistance cooperation with ASEAN countries has gone through the initial, growth, adjustment and development stage, the areas of cooperation have been gradually expanded and the cooperation modes have been constantly diversified, having a positive impact on the development of China-ASEAN political and diplomatic relations and economic and trade cooperation.

1. THE INITIAL STAGE OF CHINA-ASEAN DEVELOPMENT

ASSISTANCE COOPERATION( 1950-1970)

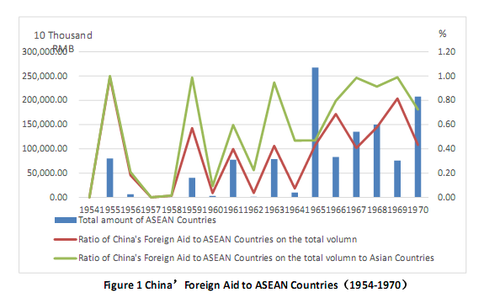

In the early days of New China, it was our urgent task to fight against the military threats and economic blockade of the Western countries. Despite of the heavy task of industrial restoration, based on the international situation at that time, China still made every effort to support other socialist countries. After the eight principles for China's foreign aid were announced at the Bandung Conference, China's foreign aid has been gradually delivered to other ASEAN nationalist countries, aid modalities have become diversified and the management system has been initially established. In this stage, except for a few years with fluctuations, China's aid to Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Indonesia accounted for 90% of its total foreign aid, especially the aid to Vietnam.

1.1 SUPPORT VIETNAM WAR AGAINST FRANCE AND THE POST-WAR

RESTORATION

Vietnam is the first country to receive China's foreign aid. From 1950 to 1954, required by the Vietnamese government, the Chinese government provided free military and material assistance worth 176 million yuan to meet the urgent needs of Vietnamese forces, institutions and people, breaking the foreign economic blockade. After the armistice, to help the Vietnamese government revive the economy and daily life, in 1954, China sent 145 experts in planning, statistics, finance, transportation, telecommunications, industry, irrigation, agriculture, commercial and financial field to help the Vietnamese government and economic sectors develop policies and programs to resume production and strengthen the management of industry and commerce, finance, market and prices, provide advice and make recommendations. According to the joint communique signed between China and Vietnam in 1955, from 1955 to 1957, China provided a wide range of economic and technical aid to Vietnam worth 800 million yuan, including cash and material support and complete projects. In 1954, China provided needed equipment and facilities and dispatched an engineering team to repair the Hanoi-Munanguan Railway, which became the first complete project of China's foreign aid. In addition, the Chinese government received 750 Vietnamese interns to learn expertise in China.

1.2 THE COVERAGE OF CHINA'S FOREIGN AID WAS EXPANDED TO

INCLUDE OTHER COUNTRIES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AFTER THE

BANDUNG CONFERENCE.

The historic Asian-African Conference was convened in Bandung in 1955. According to the "Final Communique of the Asian - African Conference" announced at the meeting, the participating countries agreed to provide technical assistance to one another, to the maximum extent practicable, in the form of: experts, trainees, pilot projects and equipment for demonstration purposes; exchange of know-how, etc. After the Bandung Conference, China's foreign relations witnessed new development. In accordance with the spirit of the Communique of the Bandung Conference, China expanded the

Total amount of ASEAN Countries Ratio of China's Foreign Aid to ASEAN Countries on the total volumn

Ratio of China's Foreign Aid to ASEAN Countries on the total volumn to Asian Countries

100coverage of its foreign economic and technical assistance from the socialist countries to Asian and

African nationalist countries and gradually expanded the assistance scale as well. In the ASEAN

region, while continuing to provide substantial assistance to Vietnam, China began to provide aid to

Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

China started to offer economic and technical assistance to Cambodia in 1956. In accordance with the assistance agreement signed between China and Cambodia, China provided free aid worth £8 million to Cambodia from 1956 to 1957 to support the material supply and the implementation of complete projects such as textile mills, plywood plants, paper mills and cement plants. After that, China provided Cambodia with free radio stations, medical facilities and other machinery equipment, and helped it set up the stadium and the International Village and expand the airport as well. China signed the first economic and technological cooperation agreement with Myanmar in 1961 and determined to issue a total of 30 million pounds of long-term interest-free loans to Burma to support complete projects and material assistance. Most of the production projects such as textile mills, paper mills, sugar mills and plywood plants, and infrastructure projects like bridge projects supported by China's assistance were completed in the mid-1960s.

China started to provide military assistance to Laos in 1959 and then signed a series of exchange of letters with the Vietnam's government. In this period, China mainly offered equipment and civilian goods to Laos, helped it build highroads and schools and dispatched medical teams to the country as well.

1.3 PUT FORWARD EIGHT PRINCIPLES FOR CHINA'S AID TO FOREIGN

COUNTRIES

In Early 1964, during his visit to 14 Asian and African countries, including Myanmar, Pakistan and Ghana, for the first time, Zhou Enlai put forward the eight principles for China's aid to foreign countries. In the next year, at the First Session of the Third National People's Congress, the eight principles were determined as the basic principles for China's foreign aid, marking China's foreign aid entered a new stage of development. At the same time, the United States launched a war of aggression against Vietnam. The Chinese Government fully supported Vietnam and provided a lot of multifaceted assistance to Vietnam. In addition, Guangdong, Guangxi, Yunnan and Hunan Province of China respectively provided free aid to 7 northern provinces of Vietnam, namely Guangning, Liangshan, Gaoping, Laojie, Laizhou, Hejiang and Heping Province.

2. THE GROWTH STAGE OF CHINA-ASEAN DEVELOPMENT

COOPERATION( 1971-1978)

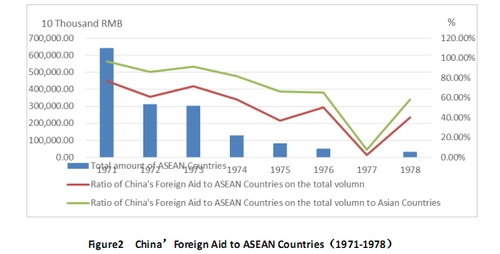

In the 1970s, great changes took place to domestic and international situations. In 1971, China's legitimate seat in the United Nations was restored, China's foreign relations witnessed rapid development and there was a significant increase in the number of the countries requesting assistance. At this stage, China's foreign aid scale expanded sharply and China mainly offered assistance to Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. From 1971 to 1976, China’s aid to the above-mentioned four countries accounted for about 80% of its total foreign aid, and Vietnam remained a major recipient country. It was the core of the foreign aid work to support Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia’s war against America for national salvation. At that time, China was in the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution. To complete the heavy task of foreign assistance and promote the foreign aid work, China successively convened five national work conferences on foreign aid. In 1977, China reduced its foreign aid scale and stopped providing aid to Vietnam.

2.1 EXPANDED THE SCALE OF ASSISTANCE SHARPLY

Under the support of the majority of developing countries, China resumed its legitimate seat in the United Nations in 1971. After that, China's international status improved significantly and its foreign relations entered the stage of unprecedented development. While negotiating with China on the establishment of diplomatic relations, many developing countries turned to China for economic and technical assistance. From 1971 to 1978, the number of the countries receiving Chinese aid reached 66 and the amount of assistance was almost twice the total sum of the aid offered in the past twenty years, accounting for nearly 6% of the gross national expenditure.

2.2 SUPPORTED THE VIETNAM, CAMBODIA AND LAOS’ WAR AGAINST

AMERICA

Since 1970, the war against the United States was in full swing in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. China continued to provide moral support and human, material and financial assistance to the three countries’ war against America. From 1971 to 1975, China's economic and technical assistance to Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos accounted for 43.4% of its total foreign aid, among which, the assistance to Vietnam accounted for 93.1% of China's total aid to the three countries. In this stage, China signed 14 economic and military aid agreements with Vietnam. In 1974, China provided Vietnam with assistance worth 2.5 billion yuan, the largest amount of its foreign aid.

2.3 COMPREHENSIVE INSPECTION OF CFAP QUALITY AND

EFFECTIVENESS

To meet the increasing requirements of foreign aid work, from 1971 to 1977, China successively held five national work conferences on foreign assistance to mobilize all sectors and regions across the country to strive to complete the task of foreign aid. 26 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities established corresponding foreign aid agencies. From 1973 to 1975, China dispatched ten inspection teams in the field of construction engineering, agriculture, roads and industry to conduct on-site inspection on more than 300 aid projects, including those in Southeast Asia, addressed the discovered problems and summarized the relevant experience, further improving the quality of complete foreign aid projects and playing a positive role in shortening the construction period and saving project investment.

3. THE ADJUSTMENT STAGE OF CHINA-ASEAN DEVELOPMENT

COOPERATION( 1979-2000)

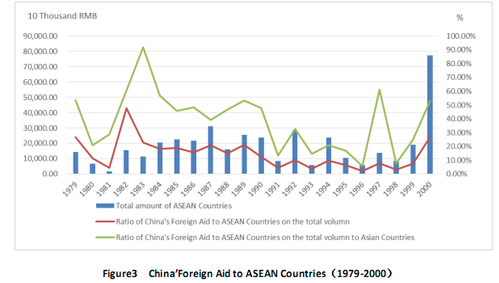

After launching the reform and opening-up policy, China continued to adjust its foreign aid work and control the assistance size. China's economic cooperation with ASEAN countries developed from simple assistance to economic and technical cooperation in various forms. In the 1990s, in the process of accelerating the transformation of a planned economy to a socialist market economic system, China gradually reformed its foreign aid modalities and promoted the diversification of the sources of foreign assistance and the aid modalities. In this stage, China provided assistance to Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam, Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia and East Timor, with annual aid amount remaining at 300 million yuan or so. With increasing assistance to Africa, the proportion of China's aid to ASEAN countries in the total was no more than 20% except for a few years.

3.1 MODEST ADJUSTMENT TO THE SCALE OF ASSISTANCE

From 1977 to 1983, due to the financial and economic difficulties, the Chinese government strictly controlled the scale of foreign aid. With the improvement of the financial situation, China expanded the scale of its foreign aid in 1984. Since 1990, China's foreign aid has remained at 2-3 billion yuan or so. Among the ASEAN countries, China’s assistance to Cambodia is relatively stable and China provided assistance to this country every year. Its aid to Myanmar, however, turned to be stable since 1983, and it gradually resumed foreign aid to Vietnam and Laos in early 1990s, but the scale witnessed fluctuations.

3.2 MODEST ADJUSTMENT TO THE KEY AREAS OF FOREIGN AID AND

THE AID MODALITIES

In this stage, China's assistance to ASEAN countries continued to develop in the adjustment and reform. Based on its financial and material conditions, China made overall arrangements on recipient countries and the use of aid funds. First, gradually reduce new production projects, consolidate the completed production projects through technical and managerial cooperation with ASEAN countries in various forms, and increase public facility construction projects. In Cambodia, for example, China launched the well-digging projects, drainage and lighting projects, school, office building and highroad projects, etc. Secondly, adjust the assistance structure and raise the proportion of complete projects and technical assistance. Thirdly, China started to issue a certain amount of donations to multilateral development institutions of the United Nations, gradually provided technical assistance to ASEAN countries through a combination of bilateral and multilateral assistance, including dispatching experts to give lectures on technologies and carry out feasibility research on development projects, providing small demonstration facilities and teaching how to use the equipment.

3.3 INTRODUCTION OF CONCESSIONAL LOANS

To tap new sources of aid funds and effectively expand the scale of assistance, in 1995, China began to issue government subsidized concessional loans: The Export-Import Bank of China provided mid- and long-term low-interest loans to foreign countries as government assistance. The principal was raised on the market, the interest rate was lower than the benchmark interest rate announced by the People’s Bank of China, and the government shall provide financial subsidy for the interest margin. In this stage, Laos launched the construction and expansion of Wanrong Cement Plant with China's preferential loans.

3.4 COOPERATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN RESOURCES

China started to conduct cooperation in the development of human resources in the implementation of aid projects. Based on the needs of Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and other ASEAN countries, China received interns of more than 20 industries, including agriculture, water conservancy, light industry, transportation and health industry to study in China. Since 1981, in cooperation with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), China has held practical skills trainings in a few fields for developing countries, including the ASEAN countries. In 1998, China began to hold seminars for officials of developing countries and trained management and technical personnel for ASEAN countries, covering more than 20 areas, such as economy, diplomacy, agriculture, medical treatment, public health and environmental protection.

4. THE DEVELOPMENT STAGE OF CHINA-ASEAN DEVELOPMENT

COOPERATION( 2001-2012)

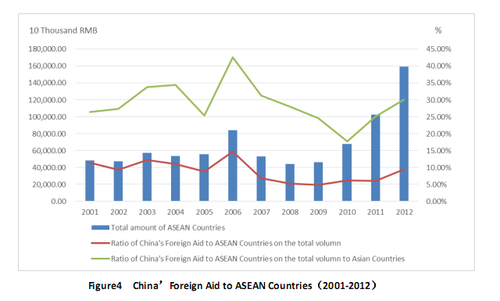

In the new century, with the further development of economic globalization, China's comprehensive national strength jumped sharply and foreign aid capability was significantly enhanced. China vigorously promoted the reform and innovation of foreign aid work and launched all-round cooperation with ASEAN countries. Since 2005, China has proposed to build a harmonious world, actively promoted the realization of the UN Millennium Development Goals, and made use of the mechanism for China - ASEAN regional economic cooperation to constantly launch assistance initiatives. In this stage, China mainly provided assistance to Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam, Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia and East Timor, and its aid to Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia was mainly used for emergency humanitarian assistance and human resource development cooperation. China's aid to ASEAN countries accounted for no more than 20% of its total foreign aid, remaining relatively stable.

4.1 PROMOTE THE REALIZATION OF THE UN MILLENNIUM

DEVELOPMENT GOALS

Since 2001, the overall size of China's foreign aid was gradually expanded. At the UN Millennium Summit held in September 2009, world leaders developed a series of time-bound goals, known as the Millennium Development Goals on the eradication of poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy, environmental degradation and discrimination against women, which are planned to be achieved by 2015. While adhering to the path of peaceful development, China has actively undertaken its international responsibilities, put forward foreign aid measures successively at the UN High-level Meeting on Financing for Development and the United Nations High-level Meeting on the Millennium Development Goals, strived to promote the South-South Cooperation on the basis of achieving domestic goal of poverty reduction and actively helped developing countries, including ASEAN countries to shake off poverty, making a contribution to the realization of the UN illennium Development Goals.

4.2 PROPOSE FOREIGN ASSISTANCE INITIATIVES UNDER THE

MECHANISM FOR CHINA-ASEAN REGIONAL ECONOMIC COOPERATION

While providing bilateral aid to ASEAN countries, China actively made use of the mechanism for China-ASEAN regional economic cooperation to develop and launch assistance initiatives. In 2005, at the 9th ASEAN+3 Summit, Premier Wen Jiabao said that about one-third of the $ 10 billion of preferential loan announced at the UN High-Level Dialogue on Financing for Development would be issued to the ASEAN countries and, on this basis, China would increase preferential loans of $ 5 billion. The aid initiatives announced by Yang Jiechi in Beijing when he met with the envoys of ten ASEAN countries in China in 2009 include: To provide special aid of 270 million yuan to Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar; to implement the "Action Plan for Upgrading China-ASEAN Comprehensive Grain Production Capacity"; and to increase 2000 government scholarships and 200 scholarships for Master of Public Administration in five years. In the same year, at the 12th ASEAN-China Summit, Premier Wen Jiabao announced that among the credit loans of $ 15 billion for ASEAN countries, the preferential loans will be increased to $ 6.7 billion, and China will actively promote the implementation of the "Action Plan for Upgrading China-ASEAN Comprehensive Grain Production Capacity" and the "China –ASEAN Rural Development Promotion Plan"; strengthen cooperation in biodiversity conservation, environmental protection and the field of new energy, train 100 environmental officials for ASEAN countries in three years; and strengthen social and cultural exchanges as well. Over the years, China has actively implemented the above assistance initiatives.

4.3 MAKE USE OF PREFERENTIAL LOANS TO LAUNCH MORE LARGEAND

MEDIUM-SIZED AID PROJECTS

Since the beginning of the new century, especially since China announced a preferential loan of $ 5 billion to ASEAN countries in 2005, China has successively launched more than one hundred preferential loan projects in cooperation with Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar, Indonesia, the Philippines and other ASEAN countries, involving the procurement of large equipment and aircraft, infrastructure construction, communication information, agricultural irrigation, hydropower, industrial production, etc.

4.4 A WIDE RANGE OF SERVICE AREAS FOR FOREIGN AID VOLUNTEERS

In May 2002, for the first time, China dispatched five young volunteers to provide a six-month voluntary service in the field of education and medical service in Laos. As of the end of 2012, China dispatched 93 foreign aid volunteers to four ASEAN countries, namely Thailand, Laos, Myanmar and Brunei, including 18 to Thailand, 37 to Laos, 15 to Myanmar and 23 to Brunei. The volunteers provided services in the field of language teaching, physical education, computer training, diagnosis and treatment of traditional Chinese medicine, agricultural science and technology, arts training, industrial technology, social development and international aid for the local residents.

4.5 INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN RELIEF

When relevant countries and regions suffered a variety of serious natural disasters or humanitarian disaster, China actively participated in the foreign emergency rescue activities and provided emergency relief supplies, cash or sent rescue workers to mitigate the loss of life and property of people in disaster areas and help the affected countries cope with the difficulty situations caused by disasters. To make the rescue activities more quickly and efficient, China established the humanitarian emergency response mechanism in September 2004. After the Indian Ocean tsunami in December 2004, China launched the largest-scale emergency relief activity in the history of its foreign aid. It provided a total of more than 700 million yuan of relief funds to the affected countries, including Indonesia and Thailand, and dispatched rescue teams and medical teams to the relevant countries. As of 2013, China had successively provided emergency technical assistance to combat bird flu in the ASEAN countries, and provided material or cash assistance to Myanmar after the local cyclone and earthquakes, and provided assistance to the Philippines after the hurricanes attacked the country. When China suffered from the floods along the Yangtze River and the Wenchuan Earthquake, it received selfless assistance from the ASEAN countries.

5. MAIN FEATURES OF CHINA-ASEAN DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE

COOPERATION

5.1 DIVERSE COOPERATION MODES

China - ASEAN aid cooperation is conducted through implementing complete projects, providing materials and equipment, dispatching experts for technical assistance, inviting officials and technical personnel to take part in trainings in China, dispatching medical teams and volunteers, implementing debt relief and providing humanitarian assistance, etc. The construction of complete projects has been the main approach for China to aid ASEAN countries. As of 2012, China had implemented 459 complete projects for Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia and East Timor, accounting for 21.2% of the total. China's complete foreign aid projects in ASEAN countries, in various sizes, cover a wide range of industries, including agriculture, irrigation, water supply by well digging, industry, electricity, transportation, telecommunications, culture, education, health, public facilities, etc. China also provided substantial technical assistance to ASEAN countries, which was mainly taken as the follow-up work of complete projects to help local trainees master the relevant technologies and management skills through dispatching experts and technicians. In recent years, China sent more experts to help ASEAN countries focus on economic development and share development experience, and invited more government officials and management and technical personnel of ASEAN countries to participate in the relevant seminars or trainings held in China, share experience in country governance and learn sophisticated applicable technologies.

5.2 CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC FACILITIES IS BECOMING THE FOCUS

OF FOREIGN AID

In the initial stage, to help ASEAN countries restore economic order, establish industrial system and enhance production capacity after the war, China launched a large number of production projects in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar, including sugar mills, paper mills, glass, mills, textile mills, machinery plants, fertilizer plants, cement plants, etc. In the 1990s, China gradually shifted the focus of its assistance to ASEAN countries to the construction of public facilities, including economic infrastructure and public facilities. In terms of economic infrastructure, we used free aid and interest-free loans to help ASEAN countries construct the road and hydropower station projects. After introducing concessional loans, China allocated more funds to implement a number of largeand medium-sized aid projects, such as the GMS Information Highway Project in Myanmar and Cambodia, the Telecom reconstruction and e-government projects in Laos, the light rail project in Hanoi of Vietnam and the highroad project in Cambodia, etc. As for the construction of public facilities, China mainly launched relevant public facility projects to improve the working conditions of ASEAN governments, the cultural and sports facilities and the people’s living environment, and to enhance the city's image as well, including the Congressional Office Building of Cambodia, Lao’s International Conference Centre, aid Myanmar's International Conference Center, gymnasium and cultural plaza, etc.

5.3 PROMOTE THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE

Agricultural development is essential to poverty reduction in ASEAN countries and China has always taken agriculture as the priority area for its aid to ASEAN countries. In the initial stage, China mainly helped the ASEAN countries build farms, agricultural technology experimental and promotion stations as well as fertilizer plants, provided agricultural machinery and agro-processing equipment and improved species, and dispatched agricultural technicians to guide the construction of water conservancy facilities and teach agricultural production technology. Since 2010, China continued to increase efforts on the implementation of the "Action Plan for Upgrading China-ASEAN Comprehensive Grain Production Capacity" and set up 20 experiment stations of crop varieties with a demonstration area of one million hectares jointly with the ASEAN countries; newly established three agricultural technology demonstration centers in the ASEAN countries, dispatched 300 agricultural experts and technicians to provide advice and carry out technical cooperation in ASEAN countries, and actively helped other developing countries improve agricultural productivity through organizing agricultural technology and management personnel trainings. In addition, China has trained a large number of agricultural technicians for ASEAN countries, promoted the implementation of the "China–ASEAN Rural Development Promotion Plan" and helped the ASEAN countries to enhance food production levels and strengthen agricultural development capacity.

5.4 ATTACH IMPORTANCE TO THE COOPERATION WITH ASEAN

COUNTRIES IN HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT

Adhering to the philosophy of "teaching a man to fish", China shares development experience and practical techniques with ASEAN countries through human resources development cooperation, aiming to support the personnel training and enhance the self-development capacity of ASEAN countries. In the initial stage, China provided technical assistance to ASEAN countries through dispatching experts. In the new century, while continuing the traditional technical cooperation, China increased efforts on personnel exchange and training for ASEAN countries. Since 2001, China has held more than 2,000 officials seminars, including more than 100 workshops for ministerial officials, and more than 10,000 officials from the diplomacy, finance, health, education, culture, military, judiciary and other government departments of ASEAN officials were invited to attend the events, involving economic management, political diplomacy, public administration, construction and management of development zones, vocational education, non-governmental organizations, etc. Meanwhile, China has held 357 technical personnel trainings for nearly 5,000 technicians of ASEAN countries, covering agriculture, medical treatment, public health, information technology, communication, environmental protection, disaster prevention and mitigation, crafts, transportation, machinery, arts, sports, etc. In response to the need of ASEAN countries for capacity building of senior managers in the public sector, from 2006 onwards, China has set the in-service academic education program for foreign aid. As of 2012, China had launched 19 in-service academic education projects and about 50 government officials from ASEAN countries respectively obtained a master's degree in public administration, education, international relations and international media.

5.5 COORDINATION OF DOMESTIC GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENTS

China has mobilized and drawn on the strength of domestic government departments to support its aid to ASEAN countries. China's assistance to ASEAN countries is under the management of the Ministry of Commerce. In various areas of expertise, however, the resource advantages of the relevant government departments have been given full play. In 2011, China established the inter-ministerial coordination mechanism for foreign aid, which has now 32 member units. Jointly with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Finance, the Import and Export Bank of China and the People's Bank of China, the Ministry of Commerce analyzes the aid needs of ASEAN countries every year and develops annual aid program of the Chinese government based on a rational division of labor. The Ministry of Commerce is responsible for making clear the size and structure of the aid program and the layout of ASEAN countries. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

based on the needs of diplomatic work, gives suggestions on the aid layout, while the Ministry of Finance offers the funding proposal, and the Import and Export Bank of China is responsible for the preparation of preferential loan scheme. While providing international emergency humanitarian assistance to ASEAN countries, various ministries are in close coordination and cooperation. In September 2004, the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Headquarters of the General Staff established the mechanism for foreign humanitarian emergency and disaster relief and assistance. In response to the Indian Ocean tsunami, the Myanmar cyclone and earthquakes and the hurricanes in the Philippines, China launched the emergency program. The Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs determined the aid size and contents in the shortest time and the Headquarters of the General Staff was responsible for organizing the implementing the assistance, effectively completing the emergency rescue task in ASEAN countries.

5.6 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACTIVELY INVOLVED IN THE

DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION WITH ASEAN COUNTRIES

The provinces in Southwest China are adjacent to Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia and other underdeveloped ASEAN countries. Due to the geographical proximity, ethnic similarities, close trade and economic cooperation and close contacts, Yunnan, Guangxi and Guangdong Province of China are active in providing assistance to ASEAN countries. In the 1970s, China changed the delivery person department system for foreign aid management to the construction department responsibility system to further mobilize the enthusiasm of provincial government. Yunnan, Guangxi and other provinces have successively set up the foreign aid management agencies to take charge of the management and organization of the aid projects for ASEAN countries. After the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the CPC in 1978, China has successively implemented the system of investment responsibility and the contract responsibility system for the management of foreign aid projects. The local governments of Yunnan and Guangxi are responsible for the supervision and management of the local enterprises and institutions undertaking the foreign aid task. Meanwhile, they have also actively conducted development cooperation with the neighboring regions of ASEAN countries. Through providing materials and equipment and sending technical experts in various fields, they established the agricultural demonstration bases, supported vocational and technical education, carried out exchanges and cooperation and held technical trainings, etc. Now, Yunnan and Guangxi have become the most active areas for China’s assistance cooperation with ASEAN countries in the field of agriculture, education, public health, science and technology, culture, etc.

6. OUTLOOK ON CHINA-ASEAN DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE

COOPERATION IN THE NEW ERA

In the new era, China will continue to build an amicable, secure and prosperous neighborhood with its neighbors and adhere to the philosophy of honesty, sincerity, tenderness and trust in providing mutual assistance with ASEAN countries. China should further increase foreign assistance to the ASEAN countries, especially Burma, Cambodia and Laos, make creative use of foreign assistance resources, focus on the areas of poverty reduction, infrastructure construction, cultural exchange, capacity building, environmental protection and regional peace and security, optimize the layout of foreign aid, make innovations to the aid modalities, combine soft and hard aid and pay equal attention to government and private channels, striving to enhance the self-development capacity of ASEAN countries.

6.1 FOCUS ON INCREASING ASSISTANCE TO IMPROVE PEOPLE'S

LIVELIHOOD AND REDUCE POVERTY

6.1.1 CONTINUE TO VIGOROUSLY PROMOTE THE DEVELOPMENT OF

AGRICULTURE IN ASEAN COUNTRIES

China should continue to carry out foreign aid agricultural technology demonstration in ASEAN countries to strengthen agricultural technology experimental research, demonstration, extension and technical training, guide domestic enterprises and financial institutions to conduct agricultural investment cooperation in the ASEAN countries, continue to send agricultural experts to teach farming techniques and provide policy advice and technical guidance for sustainable agricultural development, support agricultural infrastructure construction, provide farm machinery and support agro-processing, warehousing and logistics.

6.1.2 INCREASE AID INVESTMENT IN THE HEALTH SECTOR

China should actively support the ASEAN countries to strengthen health system building to raise the level of clinical care, public health and maternal and child health care, conduct vocational and technical trainings on health care, organize short-term domestic experts' gratuitous treatment and demonstration, establish professional medical institutions for ASEAN countries based on domestic advantages of sophisticated techniques and few diseases with complications, and dispatch short-term mobile medical teams to the poverty-stricken areas of ASEAN countries relying on domestic resources. Through jointly building hospitals, medical universities and key departments, China should establish a number of regional medical centers radiating surrounding countries to promote the combination of medical services and medical education. Meanwhile, we should strengthen support for community health and public health, help establish the system for disease prevention and control, enhance the public health strategy and policy formulation and implementation capacity, and optimize the layout and structure of the foreign aid medical teams.

6.1.3 EXPAND THE SCALE OF EDUCATION AND VOCATIONAL SKILLS

TRAINING ASSISTANCE

China should further strengthen its aid cooperation with the ASEAN countries in the field of education, expand the scale of teacher training to train more teachers for ASEAN countries, and provide more scholarships of Chinese government. Based on the needs of ASEAN countries for industrial development, we should help ASEAN countries set up vocational and technical schools, establish school management models, design curriculums and enhance the employability of local people as well. In the rural and remote regions of ASEAN countries, we should set up more primary and secondary schools and provide necessary teaching equipment and learning tools.

6.2 STRENGTHEN INFRASTRUCTURE CONSTRUCTION

6.2.1 FOCUS ON SUPPORTING ECONOMIC INFRASTRUCTURE

CONSTRUCTION

Based on China's ideology of "One Belt and One Road", we should make innovative use of relevant funds, promote the implementation of a number of highroads, ports, communications, electricity and other infrastructure projects, and combine the use of aid funds and other capital to promote the interconnection construction between China and the neighboring countries of ASEAN region.

6.2.2 STRENGTHEN THE CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC FACILITIES

China should continue to support the construction of well drilling for water supply, sewage and garbage disposal, hospitals, schools, libraries and other public facilities related to people's livelihood in ASEAN countries, conduct objective assessment of the actual needs of ASEAN countries and make proper arrangements for the construction of stadiums and theaters in appropriate size and other public utilities as well as government office buildings, Parliament House, conference centers and other landmark projects. To provide public goods for foreign aid, we should promote all-round cooperation with ASEAN countries, including the economic and trade cooperation, technological and cultural cooperation, etc., aiming to promote policy communication, road connection, trade flow, currency circulation and popular feeling.

6.3 JOINTLY PROMOTE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

6.3.1 STRENGTHEN TECHNICAL COOPERATION

ASEAN countries are in the development stage of industrialization and it is essential to strengthen their capacity building and enhance their capability for sustainable development. China can help the governments of ASEAN countries develop economic development plans through sending government advisers, actively carry out technical cooperation, help them prepare development planning for key industries and carry out feasibility studies of major projects, and help the relevant countries formulate development planning for the economic parks and industrial development zones. To meet the needs of ASEAN countries for economic and social development, we can explore the establishment of the National Joint Laboratory (Research Center) and advanced technology demonstration and promotion bases, support outstanding young scientists to work in China, provide technology development plan and technological innovation policy advices for ASEAN countries, and share China's sophisticated technologies and experience in the innovation-driven development.

6.3.2 PROMOTE COOPERATION IN THE FIELD OF RESOURCES

Taking advantage of our technological superiority and construction experience in the traditional energy sector, we should make reasonable arrangements for free aid and preferential loans to promote our aid cooperation with ASEAN countries in hydropower, thermal power and other industries, help ASEAN countries alleviate the difficulties in electricity supply and promote the aid cooperation in solar energy and other clean energy fields jointly with ASEAN countries. We should actively provide aid to support the water conservation construction in ASEAN countries, involving river harnessing, the construction of reservoirs, dikes, channels, pumping stations and water gates, water conservation and water ecological environment protection, etc. Taking into account the development and utilization of water resources, environmental protection, flood control and drought relief, we should help the ASEAN countries formulate the planning for comprehensive development of water conservancy and special programs as well, actively launch aid projects of forest cultivation and restoration, carry out cooperation with the ASEAN's neighboring countries in the field of forest fire prevention and pest control, and explore the implementation of wildlife protection projects jointly with ASEAN countries.

6.3.3 STRENGTHEN ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AND RESPOND TO

CLIMATE CHANGE

In order to jointly tackle climate change, China and ASEAN countries should strengthen the popularization and application of energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies, promote China's agricultural drought-resisting and water-saving technologies and biogas technology, and support the cooperation in the field of environmental monitoring and management, the protection of ecology and biodiversity, disaster prevention and reduction, pollution prevention, etc. We should share our environmental protection experience and philosophy, management mode and technical standards with the ASEAN countries.

6.3.4 STRENGTHEN COOPERATION IN THE FIELD OF DISASTER

PREVENTION AND RELIEF

China and ASEAN countries often suffer from major natural disasters, so the two sides should further strengthen cooperation in the field of disaster prevention and relief and provide the most effective personnel and material aid for each other in the shortest time after the occurrence of disasters. We may explore the establishment of disaster relief materials supply bases in Guangxi of China for the ASEAN countries and surrounding regions. In particular, China should strengthen the exchanges of experience in disaster prevention, mitigation and relief as well as post-disaster reconstruction with the ASEAN countries.

6.4 STRENGTHEN COOPERATION IN HUMAN RESOURCES AND THE

FIELD OF CULTURE

6.4.1 ACTIVELY CARRY OUT COOPERATION IN HUMAN RESOURCES

DEVELOPMENT

China should provide ASEAN countries with more opportunities for in-service academic degree education for foreign aid, focusing on trade and investment management, agricultural development policy, public health management, economic zone planning and management, law enforcement and security, inspection and quarantine and customs management, and strengthen the communications with the government management personnel of ASEAN countries as well. We could dispatch technical experts to provide vocational skills trainings for local people of ASEAN countries to enhance their employability make constant innovations to the modes of cooperation in human resource development and explore new aid modalities such as inviting scholars, management personnel and technicians to work and study in China.

6.4.2 STRENGTHEN DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION IN THE FIELD OF

KNOWLEDGE AND CULTURE

Establish the Confucius Institute in more ASEAN countries, dispatch Chinese teachers and volunteers to ASEAN countries and train local Chinese teachers. We can promote the implementation of important cultural heritage protection projects jointly with ASEAN countries, continue to support ASEAN countries to hold large-scale international cultural and sports activities, and actively support the academic exchanges between the research institutions of China and ASEAN countries.

6.5 SUPPORT THE MAINTENANCE OF REGIONAL PEACE AND SECURITY

It is crucial to maintain the peace and security in the border region between China and ASEAN countries. China and ASEAN countries should promote law enforcement and security cooperation in the field of anti-terrorism, anti-narcotics and social control, and strengthen joint prevention and control. Through providing law enforcement and security equipment and vehicles, China can improve the law enforcement hardware of ASEAN countries to some extent. Meanwhile, we should strengthen the training of law enforcement personnel for ASEAN countries to enhance the capacity of law enforcement personnel for command and control, coordination and monitoring, information processing, etc.

6.6 MAKE CONSTANT INNOVATIONS TO FOREIGN AID MODALITIES

In a certain period of time in future, engineering project construction will continue to be China's main aid modality for ASEAN countries. We should give priority to the implementation of agricultural, education, health care, water supply, electricity, environmental protection and other livelihood projects, promote local management of complete foreign aid projects and enhance the participation degree of ASEAN countries in the Chinese foreign aid projects. We should focus on strengthening technical assistance and human resource development cooperation, send more volunteers to impoverished areas of ASEAN countries to provide voluntary services, and strengthen the cultural exchanges with ASEAN countries as well.

6.6.1 GIVE EFFECTIVE PLAY TO THE ROLE OF NON-GOVERNMENTAL

ORGANIZATIONS

China should strengthen the multi-level exchanges with ASEAN countries. In terms of assistance cooperation, while adhering to the main channel of government-to-government assistance, we should explore channels for government to support NGOs and for NGOs to assist one another, and explore the implementation of aid projects by domestic NGOs with standardized management and international project construction experience in the field of poverty reduction, culture, education, health care, skills training, community development, environmental protection and emergency relief. In addition, the Chinese government can design more aid projects meeting the demands of the masses of ASEAN countries jointly with NGOs and, when conditions permit, try to cooperate with the NGOs in ASEAN countries.

6.6.2 CONDUCT INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION UNDER THE

MECHANISM FOR REGIONAL ECONOMIC COOPERATION

China - ASEAN Free Trade Area has been established on schedule and the relevant countries have carried out all-round cooperation under this cooperation mechanism. In the future, while promoting trade and investment development, we can further strengthen assistance cooperation and jointly promote poverty reduction and improve people's livelihood to achieve sustainable economic and social development. First, China can cooperate with all parties to help ASEAN's capacity building, support ASEAN to expand its international influence. Secondly, jointly develop a series of cooperation measures under the cooperation mechanism, covering interconnection, poverty reduction and human resources development cooperation. Thirdly, explore the exchange and cooperation in the field of foreign aid with old ASEAN member countries such as Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, share development cooperation experience and explore possible paths for tripartite cooperation in the region to inject new connotation to the South-South Cooperation.

CHAPTER 7 ASIA-PACIFIC ASPIRATIONS: PERSPECTIVES FOR A

POST-2015 DEVELOPMENT AGENDA

U.N. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

United Nations Development Programme

Asian Development Bank

Asia and the Pacific has made good progress towards the MDGs, though the region will still need to make greater efforts if it is to meet some important targets. Now it has the opportunity to set its sights higher when considering priorities for a post-2015 framework.

1. CHALLENGE OF POVERTY REDUCTION IN ASIA PACIFIC

The Asia-Pacific region as a whole has had considerable success with the MDGs, particularly in reducing levels of poverty. Nevertheless, the region is off track when it comes to hunger, health and sanitation – and even in areas such as poverty a number of countries are lagging some way behind. After the target date of 2015, there will therefore be a significant ‘unfinished agenda’. The region also faces many emerging threats including rising inequality and unplanned urbanization, along with climate change and environmental pressures such as pollution and water scarcity. Among the issues that will be of greatest importance in the years after 2015 are:

1.1 POVERTY AND INEQUALITY

Although levels of poverty have fallen, some 743 million people in the region still live on less than $1.25 a day. If the poverty benchmark is $2 a day, the number rises to 1.64 billion, revealing a high degree of vulnerability; some 900 million people could easily fall into abject poverty (below the $1.25 a day poverty line) due to personal misfortune or economic shocks or natural disasters. Another concern is increasing inequality. During the 2000s, while most Asia- Pacific countries enjoyed rapid economic growth, the benefits were being distributed unevenly. Between the 1990s and the latest available year, the population-weighted mean Gini coefficient for the entire region rose from 33.5 to 37.5. Income inequalities are evident between urban and rural areas, between women and men, and among different caste, ethnicity and language groups.

1.2 LACK OF DECENT AND PRODUCTIVE JOBS

One reason why the region continues to experience significant levels of poverty and rising inequality is that economic growth is not generating sufficient decent and productive employment. This is due to the nature of growth and the pattern of structural change in many countries in which workers move from agriculture into low-productivity services. A consequence has been that many people are in vulnerable employment – working on their own or contributing to family work. Without adequate systems of social protection, they have to take whatever work they can find or generate, no matter how unproductive or poorly compensated or unsafe. About 60 per cent of the Asia-Pacific region’s workers are in vulnerable employment.

1.3 CONTINUING HUNGER AND FOOD INSECURITY

Another major problem for the region is food insecurity. Asia and the Pacific accounts for more than 60 per cent of the world’s hungry people. The situation is worst in South Asia where the proportion of people undernourished is 18 per cent. A particular concern is the level of undernutrition among women.

As well as damaging women’s health, this reduces their productivity and affects the nutrition and health of their children. Many countries also have high levels of vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

1.4 AN ABIDING BIAS AGAINST WOMEN

The region is still a long way from achieving gender equality despite the successes in achieving gender parity at the three educational levels. Across Asia and the Pacific, women face severe deficits in health and education and in their access to power, voice and rights. The starkest evidence comes from skewed male-female sex ratios: in many countries households have strong preferences for male children, and take measures to exercise these. There have been some improvements in women’s health, notably in East Asia, but in South Asia women on average have shorter life expectancies. A continuing problem in many countries is gender-based violence.

Women in Asia and the Pacific are also less likely than men to own assets or participate in nonagricultural wage employment. They also tend to be informal workers – a consequence of their limited skills, restricted mobility and existing gender norms. In addition, women have the load of unpaid domestic work to which they devote large amounts of time and energy. Women also have limited political participation: the Asia-Pacific region has the world’s second-lowest percentage of women parliamentarians.

1.5 LIMITED ACHIEVEMENTS IN HEALTH

The Asia-Pacific region has not performed well on health targets compared to other MDG targets. In 2011, there were around 3 million deaths of children under five, and nearly 20 million births were not attended by skilled health personnel. While having been reduced by more than half, maternal mortality is still high, and limited access to emergency obstetric care as well as high unmet needs for modern contraceptives remain serious concerns. South Asia still accounts for the secondhighest number of maternal deaths worldwide (26.8 per cent) followed by South-East Asia. The region has performed better on communicable diseases: the spread of tuberculosis has been reversed, and in the majority of countries efforts to control HIV are also bearing fruit. This, however, needs to be sustained. But, with rising living standards, countries across the region are also facing rising levels of non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and chronic respiratory disease and diabetes.

1.6 LOW-QUALITY EDUCATION

The Asia-Pacific region has expanded children’s access to basic education. Nevertheless, as many as 18 million children of primary school age are still out of school. Even for children who are attending school, there are major concerns about the quality of their education and many drop out after primary school. Low educational attainment is partly a consequence of low public expenditure: government spending on education, relative to other sectors, is lower in Asia and the Pacific countries than in the world’s low-income and lower-middle income countries.

1.7 HEIGHTENED VULNERABILITY AND ECONOMIC INSECURITY

A common thread through many of these issues is vulnerability and economic insecurity. Many households are now facing higher levels of risk. These are often related to family or household events – such as death, disability or loss of employment of the breadwinner, or catastrophic expenditures resulting from illness of a family member. Moreover, with ageing populations, there are now more elderly people whose lifetime savings are no longer adequate to cope with the rising costs of living and health care.

Households are also increasingly exposed to external risks – particularly economic crises. The Asia-Pacific region has been subjected, for example, to the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, and to the global financial crisis since 2008. Families across the region have also faced rising food prices. In addition, there are external risks to health: in 2003 the region experienced the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and it is continuously exposed to emerging and re- emerging public health threats.

Economic insecurity is heightened in the absence of decent and comprehensive social protection systems. Public social security expenditure remains low at less than 2 per cent of GDP in the one-half of countries where data are available. More than 60 per cent of the population of the Asia-Pacific region remain without any social protection coverage.

1.8 RAPID DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE

Across the region people are living longer, and fertility rates are falling. These are signs of success but also present new problems – as some countries have to deal with higher dependency ratios of the elderly, other countries face the challenge of a large youth bulge. While the increase in the proportion of working-age population in many countries in the region can yield demographic dividends, it also poses the challenge of creating enough decent and productive jobs.

1.9 UNPLANNED URBANIZATION

Every day an estimated 120,000 people are migrating to cities in the Asia-Pacific region and between 2010 and 2050, the proportion of people living in urban areas is likely to grow from 42 to 63 per cent. This is partly caused by demographic change. But more importantly this is the result of urban-biased development driven by globalization and the consequent lack of adequate opportunities in rural areas.

1.10 PRESSURE ON NATURAL RESOURCES

Economic growth, driven by industry and manufacturing, has largely relied on the exploitation of natural resources. At the same time, the patterns of consumption and production have become increasingly unsustainable and are taking a severe toll on the environment, posing a real threat to the planet – with heightened levels of air and water pollution. Water supply issues are also becoming more complex and difficult.

1.11 EXPOSURE TO DISASTERS

The region is the world’s most disaster-prone area and faces increasing risks of disaster. Between 1970 and 2010, the average number of people in the region exposed to yearly flooding, for example, increased from 30 million to 64 million, and the population living in cyclone-prone areas grew from 72 million to 121 million. Moreover, the impacts of disasters are being transmitted across national boundaries: as Asia- Pacific countries become interlinked through regional value chains, a catastrophe in one country can have significant knock-on effects elsewhere.

1.12 THE RISING THREAT OF CLIMATE CHANGE

The Asia-Pacific region will be hard hit by a changing climate. This is likely to undermine both food security and livelihoods, and bring huge economic and social costs. Small island developing states in particular will be confronted with rising sea levels. While most of the accumulated CO2 has come from the developed countries, an increasing contribution is coming from Asia and the Pacific. For tracking CO2 emissions in the region, however, the perceived outcome depends on the measure: the region as a whole is an ‘early achiever’ when emissions are considered in relation to GDP, but regressing or making no progress in reducing CO2 emissions per capita.

2. THE MDG EXPERIENCE

The MDGs have had a major impact. They have caught the popular imagination – through their engaging simplicity, quantitative targets, comprehensible objectives, and laudable intentions. They have helped rally political support for global efforts to reduce poverty and achieve sustainable human development.

Inevitably, they have had their limitations. The MDGs tended to focus more on the symptoms of poverty rather than on the root causes, and could not respond to all development issues. Moreover, their genesis was not fully inclusive – having litter input from civil society organizations, NGOs or other stakeholders – yet they derived from a series of intergovernmental processes and UN Summits held in the 1990s on various development issues. There has also been some debate on how the goals should be applied. They were originally intended as collective targets for the world as a whole rather than for individual countries. Subsequently, it was argued that every country should adopt every goal and target, which in some cases would set very ambitious objectives. In practice many Asia- Pacific countries localized the MDGs, adapting the targets to their own circumstances and adding new goals. The MDGs did not specify strategies. To a large extent this was deliberate. The MDGs aimed to build the broadest possible consensus around a common and uncontroversial agenda of poverty reduction. Nor were the goals presented as rights. The MDGs instead referred to people as ‘stakeholders’ and did not explicitly articulate the ‘rights-based’ approach to development. Such critiques offer important insights, and some would argue that given these weaknesses, and the likelihood that some goals will be missed, the MDGs should be allowed to expire. A more constructive approach, however, is to reconsider the strengths and weaknesses of the framework so as to fine-tune the goals and deploy their full potential.

2.1 THE IMPACT OF THE MDGS

In the absence of a counterfactual, development success cannot be unequivocally attributed to MDGs. In any case, it may be too soon to judge. Barely 10 years have passed since the adoption of the goals. It took some time for the MDGs to be accepted, adopted, and finally adapted. One criterion for success would be the extent to which the MDGs have shaped national policies. By this measure, they have clearly had an impact in some countries. A UNDP study found, for example, that the MDGs have influenced national processes and institutional frameworks in 11 Asia-Pacific countries. In addition, 14 countries across the region are applying the ‘MDG Acceleration Framework’, which helps countries identify bottlenecks and sharpen strategies for stepping up progress. The MDGs have also opened up a huge space for civil society. Grassroots organizations, think tanks and NGOs have used them to push their respective agendas – on gender equality, for example, health, education, and human rights – and to highlight wide inequalities, showing how the MDG achievement within countries has been uneven – much lower in poor regions and for disadvantaged or excluded groups.

Another legacy of the MDGs is the improved monitoring and dissemination of social data. The MDGs provided a relatively simple monitoring framework. Almost all countries in the region prepare national MDG reports. Nevertheless, there are still many data gaps.

2.2 LEARNING FROM THE MDG EXPERIENCE

The MDGs have contributed to a wide body of knowledge – for governments, civil society and international organizations. This will be invaluable in designing a new framework. This experience suggests that the new framework should enable: Greater integration – The existing MDGs were articulated goal by goal. A post-2015 framework should better reflect the reality that goals are multi-dimensional, multi-sectoral and interdependent – allowing for coordinated action on several fronts.

More ambitious gender goals – By and large, the MDGs have not delivered on gender. The MDGs gender focus was limited and weak in such areas as universal access to sexual and reproductive health or violence against women and girls. Moreover, progress on gender equality cannot be based exclusively on gender-related goals. Rather, gender priorities need to be incorporated into each goal.

A greater focus on emerging environmental problems – The environmental targets within Goal 7 were to some extent considered in isolation, and did not, for example, address the environment-poverty nexus, or reflect people’s vulnerability and exposure to disasters, or put major emphasis on climate change.

Renewed partnerships for development cooperation – Goal 8 of the MDGs was weakly formulated, hard to track and was only partially monitored. As globalization deepens, a new framework will need to reassess regional and global cooperation and governance, recognizing changes in global economic realities as well as the Rio principles.

3. DESIGNING A NEW FRAMEWORK

To gather views on a potential new development framework, the ESCAP/ADB/UNDP Regional Partnership on the MDGs undertook a series of subregional consultations, and one dedicated to the least developed countries – bringing together stakeholders from government, civil society and United Nations agencies. The consultations concluded that the post- 2015 development agenda should drive transformative change – serving as an advocacy tool, a guide for national and global policies, and an instrument for policy coherence. The consultations also reflected the desire to build on the region’s experience of adapting goals to national circumstances. Those attending the workshops gave their personal views on what should be the main priorities: their most popular choices were ‘quality education for all’, closely followed by ‘eradicating income poverty’. There was also broad consensus on the need to pursue inclusive economic prosperity, social equity and environmental responsibility. Participants believed that the new framework should enable people-centred development and incorporate the principle of universality of social protection, combined with specialized social assistance for the poor.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR A SUCCESSOR FRAMEWORK

This report argues that a successor framework should not only complete the unfinished agenda and aspirations of the MDGs but also tackle emerging issues not conceived of in the original framework. Drawing from Asia-Pacific perspectives, it presents some core principles. The new framework should be:

1. Based on the three pillars of sustainable development – The pillars cover economic, social and environmental dimensions of development transformation. This would entail a people- centred approach that puts a strong emphasis on equity, social justice and human rights for the current and coming generations.

2. Underpinned by inclusive growth – Sustained economic growth provides increased incomes that enable households to lift themselves out of poverty and gain greater access to education and health opportunities. But sustained growth will only maximize social outcomes if it is inclusive.

3. Customized to national development needs – The new framework could specify overall shared global goals, while individual regions or countries could identify the most appropriate targets to meet those goals and adopt indicators to measure their progress.

4. Embedded in equity – Development gains should not systematically bypass sections of the population. This principle can be operationalized by ensuring that indicators under the eventually selected goals track not just aggregate or average progress, but also progress at the lower end such as the bottom quartile. Hence development policies must address social and economic gaps in outcomes, access and opportunities.

5. Backed by identified sources of finance – Notwithstanding the continuous relevance of ODA, governments in Asia and the Pacific will need to mobilize more domestic resources and seek out and leverage innovative financing mechanisms. At the same time, governments will need to use public expenditure more effectively.

6. Founded on partnerships – The primary responsibility will rest with countries, but in a globalized world each country also has to deal with many cross-border spillovers whose solutions will rely on regional and global partnerships. While the agenda will be relevant to all countries, institutions and people, the responsibilities of implementing it should be shared in accordance with capabilities.

7. Monitored with robust national statistical systems – A new framework is likely to put statistical systems under greater pressure. It should therefore incorporate key measures of statistics delivery – setting targets for the development of new and improved existing datasets, including the strengthening of national statistical systems for policy analysis, advocacy and monitoring.

4. GOAL AREAS FOR THE NEXT FRAMEWORK

The post-2015 goals should set a transformative agenda for Asia and the Pacific. Based on the above core principles, this report proposes the following goal areas:

1. Zero income poverty – The region should build on its recent achievements in poverty reduction and set an ambitious goal of ‘zero poverty’.

2. Zero hunger and malnutrition – The aim should be universal food security, through among other things, much more attention to agriculture.

3. Gender equality – Gender will need to be assessed comprehensively, with more indicators on empowerment and on violence against women.

4. Decent jobs for everyone of working age – This would require full and productive employment and government commitment as an ‘employer of last resort’ translated into an explicit recognition of employment goals and targets in all policies and programmes.

5. Health for all – Priority should go to maternal, newborn and child health, universal access to sexual and reproductive health, including family planning, and to reducing the prevalence of communicable diseases and controlling the spread of non-communicable diseases.

6. Improved living conditions for all – Everyone should have access to safe and sustainable drinking water and sanitation, as well as basic energy services.

7. Quality education for all – This should start with early childhood care and education, followed by higher quality education at all levels, including adult literacy and lifelong learning, and providing learning and life skills for young people and adults.

8. Liveable cities – The poorest city dwellers should have effective shelter and secure tenure along with essential social infrastructure. They should also have access to affordable, safe and energy-efficient mass transport.

9. Environmental responsibility and management of natural resources – This will mean protecting critical ecosystems while reducing resource intensity and avoiding overexploitation of natural capital. At the same time countries will need to address climate change.

10. Disaster risk reduction – The region has witnessed natural disasters that have wiped out long-term development efforts. Any new development agenda should help mainstream disaster risk reduction in national budgets and development programmes.

11. Accountable and responsive governments – There is a call for more accountable, transparent and effective government at both national and local levels for more capable and efficient management of public resources and service delivery.

12. Strong development partnerships and reformed global governance – Countries in Asia and the Pacific will benefit from global and regional partnerships to manage global public goods, particularly in finance, health, trade, technology transfer, environment, and climate change. The reform of global governance should reflect the Asia-Pacific ascendance in the global economy. The prospect and scope of financial and economic crises and commodity price volatility must be minimized in order to protect development gains.

4.1 FRAMEWORK SCENARIOS

The goal areas can be drawn into a framework with its architecture based on the level of ambition that eventually gains consensus. The scenarios range from the least ambitious one of continuing with the current MDG framework with some adjustments, especially on the goals relating to environment and international cooperation, to a far more aspirational model that is applicable to all countries and transformative enough to end poverty, aim for shared prosperity, and safeguard the planetary resources for current and future generations. The applicability to all countries would underline shared agendas while the customization of targets and indicators would reflect not only local circumstances, but also distinct responsibilities in accordance with the countries’ own capabilities. Global discussions are likely to gain traction as the work of the Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals intensifies.

4.2 SEIZING THE FUTURE

The MDGs have demonstrated the value of rallying global support around common objectives. This experience can now serve as the basis for an even more vigorous effort in the decades ahead. Asia and the Pacific has been in the vanguard of global economic and social development. Now it has the opportunity to ensure that future development is not just rapid but more sustainable and fully inclusive. Now is the time to reach out and seize the future – and ensure rapid and equitable progress for the region’s most vulnerable people.

CHAPTER 8 CHINA-ASEAN RELATIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF

INCLUSIVE DEVELOPMENT

LIU Qianqian68, WANG Xiaolin69

International Poverty Reduction Center in China [Abstract] Growth, poverty and inequality are three major challenges faced by China and ASEAN countries. Governments of China and Southeast Asian countries attach great importance to inclusive development and poverty reduction. Inclusive development implies that everyone should be involved in the process of development and share the achievements of development. In the international level, it also requires the inclusiveness of international relations between China and ASEAN, which, in particular, has political, economic and cultural meanings. Strengthening cooperation between China and ASEAN countries on inclusive development and poverty reduction helps build mutual trust between China and ASEAN countries, and therefore offers a breakthrough for China-ASEAN relations in general.

扫描下载手机客户端

地址:北京朝阳区太阳宫北街1号 邮编100028 电话:+86-10-84419655 传真:+86-10-84419658(电子地图)

版权所有©中国国际扶贫中心 未经许可不得复制 京ICP备2020039194号-2