Policy Study on the Challenges and Responses to Poverty Reduction in China's New Stage

An Inclusive Poverty Reduction Strategy: Challenges and Recommendations

An Inclusive Poverty Reduction Strategy: Challenges and Recommendations

Unprecedented Achievements and New Challenges

Since its reform and opening in the late 1970s, China has made unprecedented progress in the area of poverty alleviation. The number of poor, measured in terms of income and welfare parameters, has been reduced significantly. This is one of the most substantial achievements in the field of poverty reduction in Chinese history. Human and social development indicators for both poor areas and the poor population have shown a noticeable improvement. China has not only contributed significantly to global poverty reduction, but has also provided a basic foundation for the timely fulfillment of crucial UN Millennium Goals.

Although China has made substantial progress in poverty reduction, increasing inequality in income distribution has begun to limit the effects of economic growth on poverty alleviation. In the coming period, China needs to pursue an economic growth which is more inclusive, combining greater equality of opportunity and enhanced social protection with sustainable growth. Inclusive Development emphasises the importance of economic growth leading to improvements in both levels of poverty and inequality. In recent years economic growth in China has succeed in reducing poverty, but this growth has been accompanied by increasing levels of inequality, as has occurred in other rapidly growing Asian economies. This has been the case in relation not only to the distribution of income but also in relation to access to health care and educational opportunity, and more generally in relation to access to assets such as land, and markets. Inclusive Development occurs when both average achievements in these areas improve and inequalities are reduced. The importance of achieving a more inclusive development in China is clear: increasing levels of inequality in opportunity potentially can offset the positive effects of growth, as significant groups begin to feel deprived relative to others in relation to areas of human development and access to assets. China currently has a tow level of household consumption as a percentage of its gross domestic product (GDP). Relative to other middle and high income countries, China also has an unusually high rate of investment much of which is undertaken directly or indirectly by the Government. The consequences of this GDP structure is that Government’s expenditure fills the gap of inadequate investment of business sector. Government investment creates some employment opportunities, but this investment structure is dependent on resources and is focused on infrastructure development. However, some of this money could also be used to increase levels of social expenditure in areas such as health and social protection, to enable a more balanced development of the economy, shifting government expenditure from resource-dependence investment to social security and income-generation, with a focus on poorer households.

There are many specific challenges for the coming years. On the one hand, China still has about 150 million people below the poverty line of US$1.25 set by the World Bank (WB), which is a considerable number. On the other hand, from the multi-poverty perspective, the issue of poverty has become more complicated. Deficiencies in income, nutrition, health, capacity and rights are not only the result of poverty, but also are an important cause of poverty. A single dimensional poverty alleviation strategy is inadequate for solving these complicated issues.

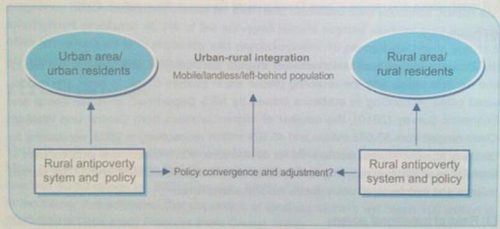

Furthermore, in the developing process of social and economic transformation, new vulnerable groups have emerged, and greater attention should be devoted to them. Aging and feminization of the rural population have also led to new challenges for poverty alleviation in rural areas, such as difficulties in developing effective mechanisms for mobilization and organization. In the process of urbanization, increasing numbers of landless peasants and migrant workers have to confront the risks of marginalization, given the absence of an urban-rural integrated social security system and appropriate poverty alleviation polices. These groups could become an important factor threatening social stability. Poverty in China no longer has primarily a rural focus, since it occurs in both rural and urban areas.

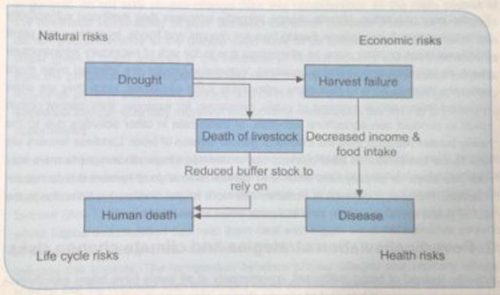

Finally, the risk of global climate change has increased, and forms a major threat to poor people living in ecologically vulnerable areas. The adverse impacts of climate change could also lead to reversals in the progress of poverty alleviation. Additionally, the 2008-2009 global economic crisis and subsequent downturn has brought uncertainties into the Chinese economy, and this downturn could still have a longer-term impact on poverty in China.

Urgent Need to Adjust China’s Current Poverty Reduction Strategy and Policies

Facing new challenges under new circumstances, China needs to adjust its poverty reduction strategy for the next ten years.

Firstly, considering overall trends in urban-rural integration and globalization, China needs to change its current system and policies, which emphasize rural poverty with separation between rural and urban areas, to an inclusive strategy integrating protection and development; it also needs to consider and address the issues of multiplicity and mobility in current poverty occurrence, so that basic livelihoods can be secured and propoor policies can benefit the poor population appropriately and timely, no matter where poor people are located. Secondly, it needs to integrate policies formulated by different government divisions into a multi-dimensional poverty reduction strategy framework, so that a “macro level poverty alleviation” mechanism can be created. Thirdly, China needs to refine its priorities in poverty alleviation and improve the accuracy of its targeting of poor households. To a large extent, this will depend on institutional arrangements for the poor population, in particular on improvements in village governance. Fourthly, China should also develop a risk prevention and mitigation mechanism on the basis of an enhanced understanding of the potential risks caused by climate change, to avoid vulnerable people succumbing to the poverty trap.

The Aim of the Report

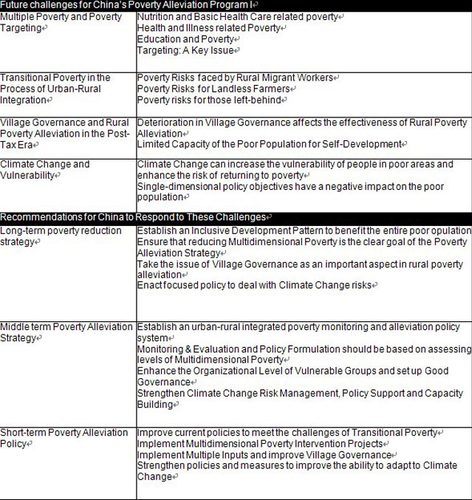

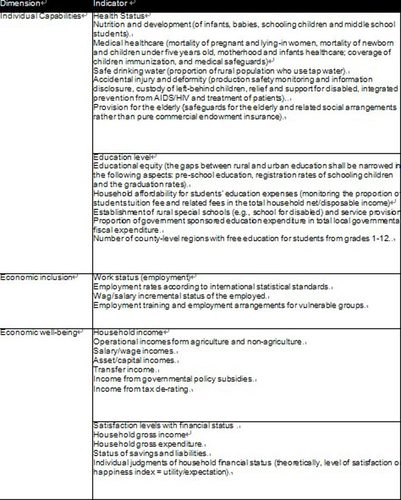

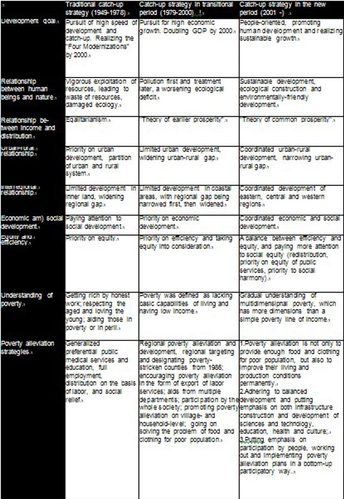

This report does not aim to produce a comprehensive analysis of poverty issues in China and the country’s poverty alleviation policies, since there is already substantial important researches addressing these topics. Rather, it focuses on relevant issues that have not been addressed adequately in previous discussions, yet which will have a considerable impact on the future performance of poverty reduction. Additionally, the report provides a number of previews for the Chinese government "as it formulates its poverty alleviation strategy for the next decade. Four major issues-multiple poverty, groups of particular relevance in transitional poverty, village governance in developmental poverty alleviation, and climate change and vulnerability-have not been given sufficient attention in research thus far, nor are they reflected adequately in China's national poverty alleviation strategies. However, these four issues will have a substantial impact on the progress and sustainability of poverty alleviation in the coming years. Consequently, they are the main concern of this report (See the policy framework in Table One).

1. Basic Profiles of China’s poverty

1. 1Changes in the Poverty Landscape

Remarkable progress has been made in the work of poverty alleviation in China. Based on the US$1 per day PPP definition, the poor population in China has declined from 730 million in 1981 to 106 million in 2005; in other words, the poor population has been reduced by 624 million in less than thirty years. According to the new poverty line of US$ 1.25 per day set by the WB, the poor population has declined from 835 to 208 million in this period, which means that 627 million people have been lifted out of poverty. Based on the line of US$2 per day, poverty has declined from 972 million to 474 million, which means that 498 million people have moved above the poverty line (Chen & Ravallion, 2008a). Therefore, it is safe to claim that in a period of twenty-five years, China has lifted at least 500 million people out of poverty.

The poverty incidence rate has been reduced even more dramatically, according to relevant data. Based on the line of US$1 per day, poverty incidence has declined from 73.26% in 1981 to 7.95% in 2005, a reduction of 65.31 percent. Based on the line of US$1.25 per day, poverty incidence has declined from 83.8% to 15.6%, equal to a reduction of 68.2 percent. Based on the line of US$2 per day, poverty incidence has declined from 97.8% to 35.7%, equivalent to a reduction of 62.1 percent.

China has also made remarkable progress in social and human development. The Human Development Indicator (HDI) for China has risen from 0.533 in 1980 to 0.772 in 2007, with an increase of 45 percent (UNDP 2009). From 1978 to 2007, the primary school enrollment rate increased from 94% to 99.5%, and the junior middle school enrollment rate increased from 87.7% to 99.9%. By the end of 2007, national coverage of nine-year compulsory education stood at 99.3%. Both boys' and girls’ primary school enrolment rate rose to above 99.5% with little gender difference. The mortality rate for children under five years-old declined from 64%o in 1980 to 18.1 %o in 2007; the infant mortality rate declined from 50.2%o in 1991 to 15.3%o in 2007; and the maternal mortality rate declined from 9.5 per ten thousand in 1990 to 3.7 per ten thousand in 2007. The under-weight rate for children under five years-old declined from 19.1% in 1990 to 6.9% in 2005; the growth retardation rate for children under five years-old declined from 33.4% in 1990 to 9.4% in 2005. The rate of safe water accessibility increased from 67% in 1990 to 88% in 2006 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, UN China agencies, 2008).

1. 2China’s Contribution to Global Poverty Reduction

China has made a substantial contribution to poverty alleviation globally. Based on the line of US$1.25 per day, the global poor population has declined from 1.896 billion in 1981 to 1.377 billion in 2005, which is equivalent to a 519 million reduction in the absolute poor population. The poverty incidence rate has declined from 51.8% to 25.2%, equivalent to 26.6 percent. In the same period, excluding China, the poor population in the rest of the world has increased from 1.061 billion to 1.169 billion, equivalent to 108 million in absolute terms. The rate of poverty incidence has declined from 39.8% to 28.2%, equivalent only to 11.6 percent. Based on the US$2 per day line, in areas other than China, the poor population has increased by 525 million (Chen & Ravallion, 2008b). These figures show that progress in poverty alleviation at the global level has been to a significant extent due to the substantial poverty reduction achieved in China.

China has already achieved four of the main UN Millennium Development Goals, namely, to halve the population below the poverty line of US$1 per day, to halve the population living in conditions of food scarcity, to ensure that all children can complete junior education, and to reduce by two thirds the mortality rate for children under five years; Other goals are likely to be completed before 2015 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, UN China agencies, 2008). China’s achievements in poverty reduction and its overall development are thus making a substantial contribution to the success of the UN in achieving its Millennium Development Goals.

1. 3The Poverty Issue is still serious in China

China is now classified as a middle income country. In 2008, its average GDP per capita, based on current prices, reached US$3,267; average national income per capita is US$2,940, and national income per capita is US$6,010, based on PPP. The majority of middle income countries adopt a poverty line above US$2. Based on this poverty line of US$2, China has a poor population of 474 million people, which means that one third of the total population is living on less than US$2 per day. In the 92 countries with supporting quantitative data, the poverty incidence rate in China is higher than that of 51 counties and is close to that of Honduras, Nicaragua and Kenya, yet relatively lower in some social and human development indicators.

2. Future challenges for Chinas Poverty Alleviation Program

There are a number of new problems and challenges that China will have to face in the next ten years to achieve its goal of large scale poverty alleviation. Poverty will become more multidimensional; new transitional poverty is emerging in the process of urban- rural integration, and this will become more prevalent; economic transformation and urbanization will lead to large scale migration, weakening rural human and material resources, and this will in return adversely affect village governance and the performance of rural developmental poverty alleviation programs. Additionally, climate change will trigger more natural disasters in ecologically vulnerable areas, which in turn will result in households falling back into poverty,

2. 1Macro level economic and social constraints

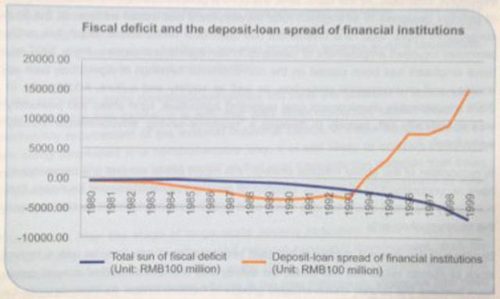

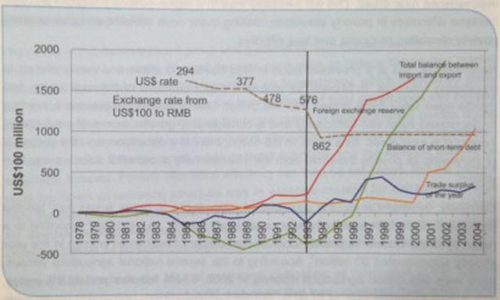

Future poverty reduction performance in China will also depend on macro-economic and social conditions. On the one hand, China's economy is encountering the “middle level income trap”. The global market which has been one of the major driving forces for China’s economic growth may stagnate due to the financial crisis. This situation is forcing China to adjust its economic structure more towards internal demand. Yet consumption remains limited within the rural population. Furthermore, increasing labor costs may reduce the competitiveness of China’s industrial goods in the global market. On the other hand, with an aging population and an increased need for social protection programs, government expenditure on these items is likely to increase, affecting the capacity of the state to invest in other areas of the economy.

2. 2Multidimensional Poverty and Poverty Targeting

Although poverty incidence measured by income and consumption is declining, viewed from a multidimensional poverty perspective, poverty remains a serious issue for China, particularly according to non-economic indicators. Conventional understanding often takes for granted that low income is the main cause of poverty; however, poverty almost always has more complex causes.

Recently there have been important developments internationally in the measurement of multidimensional poverty. This is being done via the use of a “Multidimensional Poverty Index" (MPI) with three dimensions-health, education and living standards, measured through ten indicators. These indicators are based on available data and participatory assessments. The MPI defines a household as multi-dimensionally poor if it is deprived in a combination of indicators whose sum exceeds 30% of all deprivations. Using the MPI, China currently has 7% of its population living in poverty (Compared, for example, with India at 55%, Pakistan 51%, Indonesia 21% and Brazil 8.5%). Using the MPI indicators also reveals that the highest contributor to overall poverty in China is deprivation in education. One of the most useful ways in which the MPI could be used in China might be via its use in identifying “types" of multidimensional poverty. The MPI can be “decomposed” by population sub-group, or by area. This has already been done in a number of countries, such as Bolivia, Kenya and India. These studies have revealed striking differences within each country. China has adopted multidimensional approaches in its village poverty reduction programs during the last ten years, but more specific use of multidimensional indicators could enable types of poverty to be more clearly specified.

2. 2.1Nutrition and Health related poverty

During the 18 years between 1990 and 2008, there have been large scale improvements in levels of child malnutrition in China. Yet currently, 14% of children are still suffering from slow-growth during puberty; and in poor villages this figure is 20%, falling within the middle severity category. In poor villages, rates of slow growth during puberty and numbers of under-weight children below the age of five are noticeably higher than those in normal villages and cities. A survey in poor areas in Guangxi on nutritional conditions among 1324 children under age six has shown: 22.18% children suffering from slow growth in puberty, 28.17% under-weight, 11.12% with marasmus, and 16.19% with anemia-in which children at the age of 12 months suffer from the highest rate of slow growth during puberty, under-weight and marasmus. The main factors contributing to these outcomes include low intake of dairy and meat products, thin food composition, and excessive intake of snack food. These all lead to insufficient provision of energy and protein (Fang Zhifeng, 2010). A report by the WHO has also indicated that anyone who suffers from malnutrition can potentially lose 10% of life income. This statement underlines the inherent linkage between lack of nutrition and low income or poverty.

Although China has made considerable progress in poverty alleviation in the last thirty years, it has also experienced a health crisis affecting poor households (Dummer and Cook 2007). The decline in public provision of medical and health care caused by the segregation of urban and rural policy frameworks has led directly to an increasing gap in health care resource allocation between urban and rural areas, which has further increased the cost to migrant workers of using urban health care services. In the public health sector, as a result of inadequacies in information provision and the increasing gap between rural and urban incomes, the majority of poor rural areas and the low-income population have become the target of low-quality food and medicine sellers, making poor people more susceptible to potential harm.

Illness-related poverty has become a widespread phenomenon in rural areas, within the poor population and amongst urban low-income groups. The problem of ‘difficulties in seeing a doctor’ is acute for many people in poor rural areas. Firstly, healthcare resources are concentrated in urban areas, and this has caused difficulties in accessing these services for those living in distant villages (particularly in relation to referrals for major and serious diseases). Meanwhile, because poor villagers normally cannot afford the high costs of medical care, they often try to avoid incurring costs by delaying and trying to cope with their health problems. This results in a vicious cycle of 'ignoring the minor disease, waiting until it is more serious, and when it becomes too serious, waiting to die’. In addition, due to poverty, lack of knowledge of health and low awareness of self-care, poor people are more susceptible to disease. These factors form a cycle of illness and poverty, resulting in a continual return to poverty. Lack of medical security is a serious barrier for rural people, especially those living in remote poor areas, in achieving their socio-economic goals. Although the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee and the State Council have proposed to 'gradually establish a new rural corporate medical system' in the official document on ‘Some Decisions on further strengthening rural hygienic work’, the participation rate of poor rural households is still low in many areas. Even in those projects which have a relatively high poor household participation rate, the problem of low compensation rates is still significant (Xie Huiling et al 2008). Research shows that illness as an external factor may not necessarily lead to persistent poverty, yet its impact might last for about 20 years. Finally, it is important to stress an additional key fact that children, the elderly and women are more likely to suffer particularly from illness-related poverty.

2. 2.2Education and Poverty

Educational equity has become a national issue. The main reason for education-related poverty is the high costs associated with education. High costs can lead to families and individuals falling into the poverty trap. The issue of education-related poverty has been eased to some extent following the introduction of the cost reduction policy on compulsory education, but this in itself is not sufficient. It is estimated that currently there are 5 million children of school age who cannot complete their compulsory education, and these children are mainly located in poor areas in western China. In non-compulsory education, the high cost of tuition has restricted access by many children from poor households; children from low-income and poor households drop out of school and lose educational opportunities, resulting in insufficient investment in human resources.

In particular, along with the enforcement of the ‘higher education expansion’ policy, and the marketization and globalization of higher education in the 2181 century, higher education has become a crucial issue in education-related poverty and social stratification. In addition to the impact of increases in tuition fees not being adequately monitored, the limited schooling loan and scholarship system has also resulted in an 'inverted stimulation’, namely, it does not support vocational or higher level vocational education, but is confined to post-graduate degree education. This system undoubtedly increases the social costs for poor households hoping to alleviate their poverty through educating their children.

2. 2.3Targeting: A Key issue

The issue of targeting in China’s poverty alleviation program contains two aspects: Firstly, income-oriented targeting does not take into account multiple poverty; it thus misses significant non-income poverty conditions. Many households above the income-based poverty line are actually poor because they are disadvantaged in non-income areas. The design and selection of poverty alleviation plans and projects must focus more on the income earning ability of households. Even those projects concerned with the improvement of the infrastructure, and with capacity building, are also oriented toward the goal of income growth, and do not take into account multiple development goals including nutrition, health, education, income and the equal rights of the poor population. The monitoring of poverty is also based on income and consumption and lacks a more comprehensive system for monitoring other dimensions of poverty. Secondly, income- oriented poverty alleviation projects do not benefit the poor population equally, and the problem of resource leakage is prominent. Village level development has improved the targeting rate of poor villages; but within a village, the middle income and rich households still benefit more than the poor ones.

In recent years, there have been widespread discussions internationally on targeting mechanisms within poverty reduction programme. Many researchers have concluded that targeting in poverty reduction programs contains serious problems. For example: targeting often fails to fully cover poor households; targeting in participatory programes frequently results in elites capturing benefits; decentralized targeting often is characterized by corruption, thereby worsening inequality locally.

Until recently, most poverty reduction programs used approximate indicators to identify poor households. These indicators varied from estimates of basic needs to calculations of average incomes in a particular village, area, or region. Using poverty mapping techniques, and combining this with data from household surveys (thereby allowing linkages between consumption levels and household characteristics) is a much more rigorous approach, and this has been introduced recently in some countries, notably in India, Indonesia and the Philippines. Targeting has undoubtedly been most successful where it has been based on multidimensional poverty indicators and where it aims to promote sustainable development out of poverty. The index of participatory poverty reduction adopted in the village-based poverty reduction programmes in the past ten years is considered an accurate targeting tool. However it has not been widely used due to high costs of implementation and uses of complicated techniques.

2. 3‘Transitional Poverty’ in the Process of Urban-Rural Integration

'Transitional poverty’ is closely related to the process of urban-rural integration. In the past thirty years, China has experienced the largest population migration in its peacetime history (WB 2009). This has created about 150 million migrants and their overall numbers are still increasing. This process of migration will continue for the next fifteen to twenty years. While the workforce in rural areas moves to cities and forms large numbers of migrant workers, it also creates a considerable number of "left-behind” people in rural areas, notably the elderly, children and women. This remaining “left-behind” population currently includes about 58 million children, 20 million old people and 47 million women, totaling 125 million people -a little less than the total number of rural migrant workers. On the other hand, rapid growth in the production of non-agricultural goods in the rural economy, and the rapid growth of urbanization have also increased demands to convert agricultural land to other uses, resulting in approximately 40 to 50 million farmers losing their land (Han Jun 2005).

In China, transitional poverty groups mainly include: migrant workers who work in cities yet lack adequate job security and protection from work injuries, health risks and experiencing inadequate security in elderly life; farmers who lose land, who do not benefit equally from appreciation in the value of land, and have insufficient access to the social security system; children and elderly who are left behind in the rural areas and are unable to be cared for by parents or sons and daughters; and women who are informally employed and lack adequate rights protection.

The risks that vulnerable groups have to face in the process of urban rural integration differ from the risks faced by groups experiencing conventional income poverty. Transitional poverty is generated in the process of moving from urban to rural areas. Specifically, it has the following characteristics:

Firstly, identifying the population in transitional poverty necessarily involves a degree of uncertainty. Since the main risk for this group is vulnerability, only some of them will actually fall below the poverty line due to difficulties in coping with risks.

Secondly, transitional poverty is multi-dimensional, and thus those who fall into this category may not present as low income, rather they will be socially excluded, lacking equal access to public services, experiencing a meager spiritual life, and be short of development opportunities.

Thirdly, the territorial distribution of those in transitional poverty is uneven. Migrant workers and landless peasants are mainly concentrated in the south-east coastal area and in large and middle-size cities, particularly the latter. On the other hand, the left- behind population are concentrated mainly in the rural areas in the middle and west of China.

Fourthly, transitional poverty will leave some of the temporarily-impoverished population in a permanent poverty trap.

Fifthly, policy-related poverty is a key aspect of the transitional group. Problems such as insufficient social security provision, inadequate medical provision, discrimination in the job market, and difficulties in enjoying the advantages of urbanization should all be considered as policy related issues.

Sixthly, women's poverty is also prominent. Both those women who work in mobile positions and those left-behind face many problems-such as severe deprivation of their rights, psychological problems, hardship and poor health care. These problems not only affect the wellbeing of women themselves, but also reinforce inter-generational transmission of poverty.

Finally, transitional poverty is not permanent, but policy-sensitive. The main cause of transitional poverty is deficiency in the policy system rather than the inability of the poor. It is the macro-level policy system that defines urban-rural segregation, public service policy, and anti-poverty policy approaches, and which cannot cover adequately vulnerable groups emerging in the process of urban-rural integration. This population is thus unable to cope with the risks associated with poverty. Therefore, improving the policy framework of urban-rural integration is key to solving the issue of transitional poverty.

2. 3.1Poverty Risks facing Rural Migrant Workers

Unstable employment and heavy workloads: Surveys show that in 2009 of those rural migrant workers who worked as employed staff, only 42.8% had a signed contract with their employers; 89.8% had a weekly working time in excess of 44 hours (regulated under the “labor law”); those who are employed in the hotel and catering industries work more than 60 hours per week.

Lack of medical and personal safety guarantee: In 2009, only 7.6% of employers paid pension insurance for rural migrant workers; 21.8% paid work injury insurance; 12.2% paid medical insurance; 3.9% paid unemployment insurance; and 2.3% paid reproduction insurance. The percentage of insured migrant workers in the eastern region is noticeably higher than in the middle and western areas.

Risks from illness: Rural migrant workers have problems with low income, poor living conditions, hygiene and safety conditions, low awareness of HIV/AIDS prevention, lack of access to medical care, and insufficient guidance on how to cope with HIV/ AIDS. In addition, migrant workers normally have greater mobility, and since urban and rural medical services are not well connected, this makes it more difficult to trace the prevalence of HIV/AIDS. Once infected, it becomes not only a serious problem for the patient and family, but increases society’s burden. (Li Shaoqiang 2009). Consequently, HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment for rural migrant workers will also be an important health risk and management issue in poverty alleviation and economic development in the next ten years.

Social exclusion: In practice, discrimination against migrant workers is not only experienced at the level of legal and institutional arrangements, but also through bias and exclusion at conceptual, psychological and cultural levels. (Xuyong, 2006). Furthermore, the latter is normally more lasting and thus more difficult to eliminate than the former. Social exclusion reinforces the segregation of social strata, and thereby functions to keep rural migrant workers at the bottom of society.

inter-generational poverty risk: Children of rural migrant workers cannot enjoy educational rights equal to those of children of residents in cities; this will result in an Increased educational gap between rural and urban children. Poverty can thus be transmitted from one generation to another.

Particular risks faced by female rural migrant workers: According to the large- scale survey carried out by the National Coordination Team on Women and Children’s Rights (2007), in 2006, only 36.4% of work units enforced the full length of legal maternal leave for female migrant workers; only 12.8% reimbursed the costs associated with reproduction; 64.5% did not pay for maternal leave; 58.2% of female workers needed to go back to their original place to have pregnancy checks instead of having these in their place of employment; this not only caused them considerable inconvenience, but also increased women migrant workers 'economic burden’ and difficulties in accessing jobs. Female migrant workers have stated that very often they feel exhausted, with 46.3% being ‘extremely tired’. This figure is 18 percentage higher than that for male migrant workers, and 11.5 percent higher than that for women remaining in villages.

2. 3.2Poverty Risks for Landless Farmers

Risks from unemployment and reduced incomes: Some landless farmers have obvious disadvantages in job markets due to their lack of non-agricultural skills, and a large proportion remain unemployed or semi-unemployed. Surveys show that the most difficult task that landless peasants face is to obtain new skills for other occupations. Additionally, the unemployment rate among the elderly who cannot easily adapt to new economic requirements and the number unskilled is increasing (State Council Development Research Center, 2009).

Lack of social security system: Only a relatively small number of landless peasants can enjoy the same social security service as urban residents. Most form a marginal group living in a social security vacuum.

Deprivation of social capital: Land deprivation also disaggregates the social system that is tied to the land such as the ties between distant relatives, neighbors, lineage members and community members; thus, whilst farmers lose their land, they also gradually lose their former social capital. A survey shows that 48% of interviewed landless farmers do not identify themselves as urban citizens (Yu Xiaohui, Zhang Haibo, 2006).

2. 3.3Poverty Risks for Those Left-behind

Psychological problems: Many of the left-behind children have much looser contact with their parents than their peers, thus they are inclined to experience more psychological problems and pressures (National Womenof the left-b Children Work Division. 2008).

Some left-behind women cannot stand the loneliness, and divorce rates increase (China Communist Party News network, 2009). Because children are not at their side and in most villages public cultural facilities and activities are scarce, nearly 50% of the left- behind elderly feel under pressure, and one third of them often feel lonely, and are frequently anxious, irritable and depressed (Ye Jingzhong 2008).

Health risks: The health conditions of many of the left-behind elderly are poor, and they lack caring in their daily lives and have heavy workloads. Many do not have sons or daughters at their side to take care of them when they are ill. Given the prominent trend of feminization of agriculture work (Zhen Yan 2008), the work intensity of left-behind women is increasing dramatically, and this not only seriously affects their health but also increase their susceptibility to disease; Yet many are unable to afford medical costs (Ye Jingzhong 2008).

Inadequate pension system: Surveys have shown that 81% of the left-behind elderly are still engaged in agricultural production; only 8% have obtained support from the state in cash or kind; and only 1% have social endowment insurance (Ye Jingzhong et al, 2008). This situation can only be improved when new rural endowment policies are enforced.

2. 4Governance Mechanisms: An Important Factor Influencing the Poverty Issue in the Future

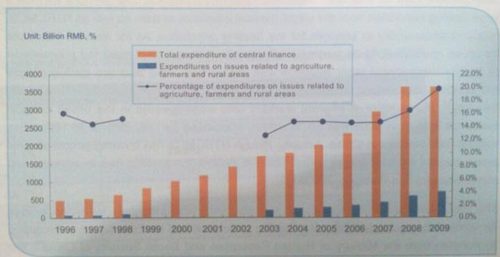

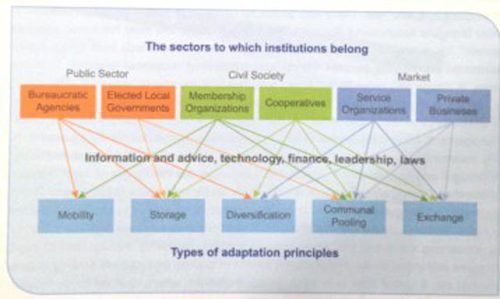

Given the Chinese Central Government’s aim of taking income redistribution as a new agenda in its development strategy, various departments will sooner or later be involved in the overall development planning process, with social protection as its main concern. Therefore it is likely that more governmental agencies will take part in the poverty alleviation program in the future; consequently, there will be a growing demand for the establishment of efficient coordination across bureaucratic boundaries and a sound governance mechanism.

In rural areas, prior to the abolition of agricultural taxes, village organizations had clear behavioral goals, structure and functions, and also had the legitimacy and means to mobilize funding and resources. With fee reform and the ending of agricultural taxes, rural areas entered a new post-tax era. This change has had important consequences for village governance. On the one hand, village public facility construction has experienced difficulties due to the pressure of grass-roots level debt and limits on expenditure; on the other hand, the connections between farmers and village cadres have become looser, and the behavioral choices of village elites have focused less on the overall needs of the village community. Furthermore, the material foundation of village administrative authority has weakened, and there appears to be a "vacuum” in village public authority (Tian Xianhong, 2006). This situation seriously affects the ability of the grass-roots community to mobilize resources and is also the root cause of village rent-seeking and the unequal distribution of resources.

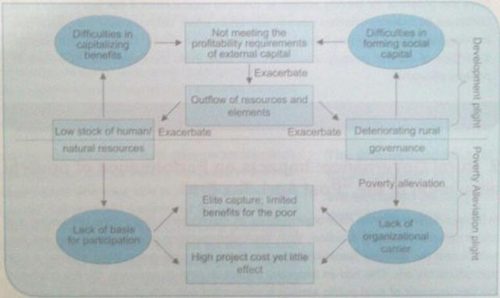

2. 4.1Deterioration in Village Governance affects the Effectiveness of Rural Poverty Alleviation

The impact of weak village governance on poverty alleviation is mainly manifested as ‘elite capture’- atomized villagers lack organizational carriers and junior officials come to dominate resource allocation. Considerable research has been carried out internationally on elite capture in recent years. It has been analyzed as resulting from a combination of factors; unequal access to economic resources, knowledge and manipulation of political processes, higher levels of educational attainment and privileged networking. As a result of the dominance of village elites, poor groups comprised mainly of women and the elderly cannot effectively participate in various projects due to their limited capacity and lack of access to resources. This situation has entrenched existing difficulties in poverty alleviation: on the one hand, due to the lack of existing organizational carriers, there are high costs associated with re-organizing weak groups in villages who are short of human, material and natural resources, and on the other hand, this will in turn affect the efficiency of poverty alleviation work.

2. 4.2Limited Capacity of the Poor Population for Self-Development

In the post-tax era, since the poor population formed largely of women and the elderly has limited capacities and access to use of natural resources, they have limited assets. Focusing on villagers use of assets - financial, physical, natural, social and cultural - is an approach used increasingly in poverty reduction programs internationally. It enables implementing agencies to target funds more directly to particular aspects of household's livelihoods to facilitate the capacity of household members to lift them out of poverty. In the context of poor village governance it is difficult to mobilize weak groups to form multi-functional and multidimensional social capital, and thus difficult to match the requirements and demands of external capital investment.

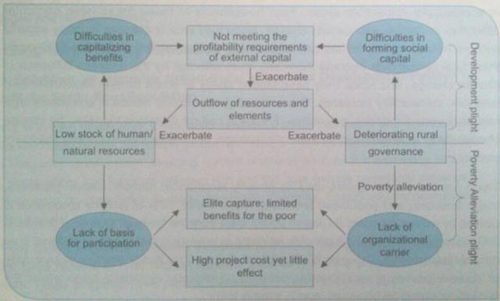

Fig. 1: How Deteriorating Rural Governance Affects Poverty Alleviation in the Post Agricultural Tax Period

This situation aggravates the outflow of resources from poor areas, which in turn lowers resource storage in villages and undermines the foundations for good village governance. This cycle limits the development capacity of women and the elderly, and puts them in a continuously self-weakening situation, constraining the possibilities for sustainable development of the village economy. Figure one illustrates this resource flow - governance - poverty alleviation interaction mechanism.

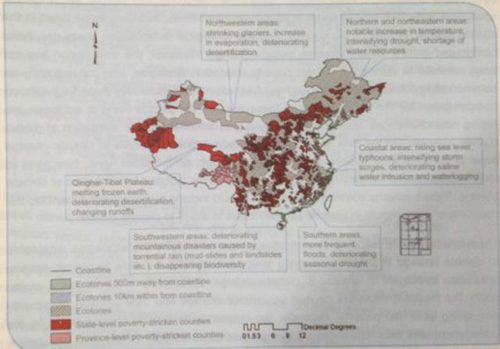

2. 5Climate Change and Environmental Deterioration: The Causes of Poverty as Defined by Vulnerability

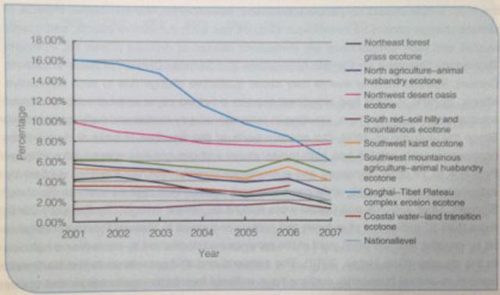

Many of China's poor areas are also highly sensitive to climate change. In 2008, the China Environment Protection Ministry issued ‘Guidelines for National Ecologically Vulnerable Areas Protection and Planning', in which eight ecologically vulnerable areas are circumscribed. These are: northeast forest-grassland ecotone, northern farm-pastoral ecotone, northwest oasis-desert ecotone, southern hilly region of red soil, karst rocky deteriorated mountains region, southwest mountain farm-pastoral ecotone, complex erosion region in Tibetan Plateau, coastal water-land ecotone (MEP 2008).

Most of China's poor population lives in these areas. In 2005, there were 223.65 million poor people nationwide, of which more than 95% lived in the old revolutionary areas, ethnic minority areas, distant areas and poor areas, where ecological conditions are also extremely vulnerable (MEP 2008). Amongst the 592 key poverty alleviation counties, which are scattered in middle and western areas, more than 80% are located in ecologically vulnerable areas (MEP 2008). Green Peace and Oxfam have jointly issued a report showing the high degree of overlap between poor counties and ecologically vulnerable areas in China. This report on the Chinese situation reflects conclusions reached internationally on the impact of various aspects of climate change causing households to succumb to poverty, often rapidly with the onset of landslides and flooding.

2. 5.1Climate Change Intensifies the Vulnerability of People in Poor Areas and Increases the Risk of Returning to Poverty

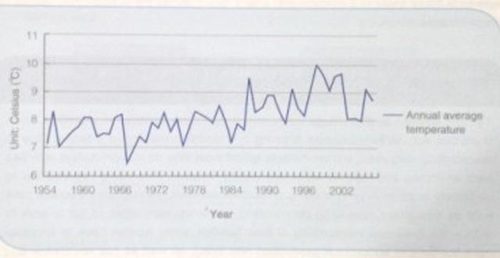

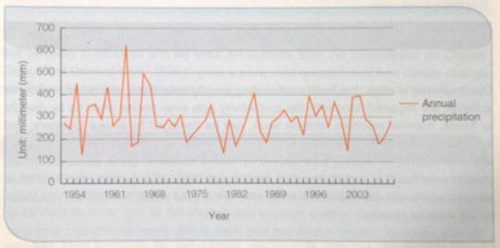

Climate change has triggered a series of natural disasters in China, such as intensified drought, the withering of forest vegetation, worsened soil erosion and extreme climate incidence. These natural disasters inevitably result in a deterioration of the environment in ecologically vulnerable areas. Poor households in these areas have particular difficulties in dealing with climate change, since they face challenges in many aspects such as natural capital, human capital, technical equipment and alternative livelihoods. Poor rural households become more and more affected by the negative influence of climate change, and since they have limited ability to adapt to new situations, their livelihood vulnerability increases. This increasing vulnerability results in a relatively high rate of poverty incidence recurrence. Frequent natural disasters triggered by climate change have gradually become the main cause of poverty incidence and recurrent poverty.

There are three main factors causing poverty recurrence: namely, natural disasters, major illnesses, and population pressure. Within these, 70% of poverty recurrence is caused by natural disasters (Li Jiayan 2005). Data from the National Statistical Bureau in 2003 showed that 55% of households returning to poverty in that year had suffered from natural disasters (Nie Zhongqiu 2007). Natural disaster may easily lead to a vicious cycle of ‘disaster-poverty-more disasters-poorer ’in ecologically vulnerable areas where the level of economic development level is already low.

The impact of this cycle has been assessed comprehensively in international research. During the last decade, considerable research has been undertaken in both developed and developing countries on the impact of climate change on poverty conditions. The vast majority of assessments conclude that poverty is one of the most powerful influences on household’s abilities to deal with the impact of climate change. Additionally, it has been concluded that poor households appear to rely more heavily on climate- sensitive resources than non-poor households

2. 5.2The Single-Dimensional Policy Objective: A Negative impact on the Poor Population

In the process of seeking an effective method to deal with climate change, on the one hand constrained by many factors, the poor population has limited ability to cope with climate change risks; on the other hand, the current policy framework does not adequately include their contributions to reducing the impact of climate change.

Effective policies, such as function-zoning, emission reduction and land conversion, sometimes may have the externa! effect of restricting the diversification of poor household’s production, and raising the cost of their livelihoods, thereby make them even more vulnerable. Policies for nature reserve areas have a multiple impact on local residents. Many natural reserve management regulations are not only about protection, but also about ecological compensation and the promotion of alternative livelihoods; however, these policies often do not take into consideration the vulnerability of the poor population, and thus may actually exclude these people to some extent.

Additionally, some measures initiated by poor groups themselves, such as cultivation regulations in drought periods and water-concentration techniques, are often not fully utilized due to resource constraints, lack of funds and technical support.

3. Recommendations for China’s Poverty Reduction Strategy to Meet These Challenges

The issue of poverty has evolved with economic development and changes in social structure. The task of poverty reduction remains complicated and enduring. It requires focusing on long, middle and short term strategies, and on specific policies to deal with the constraining factors on the poor population’o development and poverty reduction; and finally to achieve the goal of poverty elimination. Focusing on the four major issues discussed thus far, the following aspects should be included in future poverty alleviation strategies and related policies.

3. 1Long-term Poverty Reduction Strategy

3. 1.1Establish an Inlcusive Urban-Rural Integrated Development Pattern to Benefit the Entire Poor Population

From a long-term perspective, China must establish a policy framework and development model which can benefit vulnerable groups and enable them to share the fruits of urban- rural integrated development, avoiding current problems such as the increasing income gap, segregation, and tensions between rich and the poor groups commonly evidenced in the process of urbanization in many developing countries. Specifically, recommended policies include:

(a)Fully developing labor intensive industries to provide adequate job opportunities for the large number of rural migrant workers; Extending training programs for migrant workers. These programs have proven successful not only in China, but in many other countries, notably in Andhra Pradesh, India, providing employment options for vulnerable young laborers, linking them to jobs in urban and semi-urban areas, following a three month training programme with staff from industries acting as mentors. In Bangladesh, similarly successful short-term programs have been implemented for poor rural households, preparing them with skills training for work in urban and semi-urban area, and with food assistance.

(b)Establishing urban-rural unified and equal production factor markets. Enforcing the'de-elitized' household registration reform, enabling most people who are employed in cities to register. Entitle rural land with complete ownership, equalize the right and price of rural and urban land; and guarantee fair ‘compensation’ for landless farmers.

(c)Establishing an urban-rural integrated rather than a segregated or ‘fragmented’ public service policy framework, and treating urban and rural residents together as one group; set up a livelihood safety network covering and unifying urban and rural vulnerable groups at the national level. As outlined in the sub-report, international experience in this area stresses the need for policies to be “portable”. Many migrants enroll in social insurance schemes but then withdraw at a later stage because they cannot take the insurance benefits with them when they move. Additionally, often when they withdraw they can only take out their own contributions to these funds, whereas their employer’s contributions remain. To address migrant’s problems, not only must existing schemes be extended, but new independent programs must be created to meet the specific needs of rural-urban migrants. Considering the varying levels of economic development in different provinces and the current condition of fiscal transfer payments, it is suggested that each province be encouraged to unify the urban-rural public service systems within their jurisdiction, with support from the central government, to pave the way for a national integrated system as the next step.

(d)Establish a fiscal transfer payment institution which addresses the dimensions of poverty, together with a dual system of person and location affiliation. Public services such as education, medical care, pension provision and poverty alleviation should have stronger compensation mechanisms, emphasizing beneficiaries rather than their attributed locations.

(e)Fully consider the accessibility of the rural left-behind to basic public services. In the allocation of fiscal funds, address the increasing financial need to provide urban public services resulting from increasing urbanization and the need for the rural left- behind to access public services, and ensure this benefits left-behind groups, rather than maintaining or extending their marginalization when making fiscal transfer payments.

3. 1.2Reducing Multidimensional Poverty: The Goal of the Poverty Alleviation strategy

The concept of multidimensional poverty needs to be integrated into national poverty alleviation strategies, possibly via the use of the Multidimensional Index and its accompanying monitoring system. Mitigating and eliminating multidimensional poverty must become a specific objective, in relation to nutrition, health, education, income and rights, as inter-related issues for achieving the overall strategic goal. As with the UN Millennium Development Goals, it is essential to put forward a time framework, outlining specific steps and milestones for achieving the task of eliminating multidimensional poverty.

Since multidimensional poverty refers to many areas, including politics, economy, society and environment, it is necessary to establish a more effective governance structure at the macro-level to ensure that strategy and policy be inter-related and that a good partnership be established between the various departments. It is suggested to set up a responsive monitoring and evaluation mechanism to keep track of all departments in relation to their mandates and actual performances. It may also be necessary to strengthen the authority of the State Council Poverty Alleviation Leading Group and to improve the functioning of the Poverty Alleviation Office, so as to enhance its organizational capacity for coordination, and to put it in charge of monitoring and evaluation.

3. 1.3Village Governance: Taken as an Important Aspect in Rural Poverty Alleviation

From a longer-term perspective, current macro-level governance mechanisms should be reformed, based on the new challenges discussed above. The aim of reform is to establish an “overall” poverty alleviation governance system to effectively integrate administrative and financial resources. At the same time, the anti-poverty campaign first needs to guarantee the basic livelihoods of poor and vulnerable groups, and further, to support their demands for sustainable development and diversification.

The emphasis must be on enhancing the organizational level of vulnerable groups, improving the governance system and satisfying their social and cultural needs.

Consequently, it is necessary to comprehensively relate governance issues with other requirements for achieving sustainable development, such as environmental protection, and incorporate these elements into the overall policy framework for rural poverty alleviation. If we can establish an organizational structure that can absorb and utilize resources in the same process of human resource development, then it will be possible to upgrade labor resources into multi-functional and multi-dimensional social capital which can not only maintain basic livelihoods, but also promote sustainable agriculture and rural development in less developed areas.

3. 1.4Enact Focused Policy to Deal with Climate Change Risks

Poverty alleviation strategies should be sensitive to climate change risks; these strategies must be suitable for mitigating the livelihood vulnerabilities of the poor population in ecologically vulnerable areas, and enhancing their capacity for sustainable development.

The contribution that the poor population makes to reducing climate change (nature reserves/ development prohibition zones, grassland ecological construction projects and food safety projects) must be recognized and fully compensated.

The importance of drawing on community-based knowledge in assisting poor households in adapting to the adverse economic and social aspects of climate change is stressed repeatedly in many commentaries internationally. Communities often have detailed time, place and event specific knowledge of local climate hazards and of how such hazards can affect their assets and productive activities. They also have the capacity to manage local social and ecological relationships that will be affected by climate change. Communities typically incur lower costs than external actors in implementing development and environmental projects. Community knowledge has been shown to be invaluable in a range of projects, from reforestation programs to fisheries renewal, nature reserve management, and in the protection of coastal areas.

In ecologically vulnerable areas, special poverty alleviation models should be established and special fiscal budget and transfer payments should be put in place. The amount and form of transfer payment needs to be formulated, taking into consideration the aim of eliminating the threat caused by climate change risks. It is important to improve local resident's ability to cope with climate change risks in ecologically vulnerable areas where ethnic minorities are concentrated, such as the south-west karst mountainous area and stony desert covering areas of Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Chongqing and Guangxi; the south-west mountainous agriculture and pasture intersecting areas of Aba, Ganzi and Liangshan in Sichuan, Diqing, Lijiang, Nujiang in Yunnan and Liupanshui in the northwest Guizhou (containing approximately 40 cities and counties) and the Tibetan Plateau complex erosion area in Tibet and Qinghai. It is also necessary to consider the cultural development and activities of these ethnic minority communities.

3. 2Medium-term Poverty Alleviation Strategy

3. 2.1Establish an Urban-Rural Integrated Poverty Monitoring and Alleviation Policy System

Firstly, an urban-rural integrated poverty alleviation coordination and organizational institution needs to be established. It is essential to put poverty alleviation work in both rural and urban areas into one unified framework and bridge the institutional gap previously existing between the two areas; and this demands necessary reforms of the administrative system and adjustments of the functional divisions between departments.

Secondly, considering the gap in the cost of living between rural and urban areas and its variation amongst different regions, it is necessary to devise a dynamic rather than a static poverty measuring system to effectively compare rural and urban poverty.

Thirdly, the poverty monitoring mechanism needs to be adjusted, and urban and rural residence integrated into one system in order to provide complete and coherent basic data for integrated poverty alleviation policy formulation.

Fourthly, more attention needs to be paid to vulnerable groups, in relation to transitional poverty, emphasizing poverty risk factors and taking transitional poverty as an important element in enhancing development capacity and increasing the development opportunities of vulnerable groups in future macro-level strategic planning. The new national poverty alleviation guidelines should incorporate transitional poverty and the population as a crucial part of the anti-poverty agenda. This requires a change in poverty alleviation and development guidelines from those previously aiming only at the rural areas, to adopt a wider scope covering the whole country, and specifically, to integrate the urban poor, migrants and the rural poor into a unified poverty alleviation framework, and to organically consolidate the work of poverty alleviation and development, social service and social security.

3. 2.2M&E and Policy Formulation on Multidimensional Poverty

Firstly, monitoring and evaluation systems must be adjusted, based on the concept of multidimensional poverty. This adjustment should also bear in mind international research stressing the efficacy of participatory approaches in multidimensional poverty monitoring. Adjustments will require a division of tasks and coordination between member units under the Leading Group of Poverty Alleviation (LGOP). Aiming at the strategic goal of multiple poverty alleviation in the new era, it is necessary to define specific poverty alleviation targets and monitoring methods for different sectors, and to form a monitoring and evaluation system which reflects specific conditions and tasks in different departments and provinces, and which can be implemented regularly. Secondly, formulate specific plans and projects aimed at addressing multidimensional poverty. This demands coordination between the particular poverty alleviation and development policies formulated by various departments. Policy synergies will undoubtedly promotethe process of multiple-poverty alleviation.

3. 2.3Enhance Vulnerable Groups’ Organization: Good Governance

The stock of human and natural resource is generally low in poor areas and amongst vulnerable groups who are mainly women and the elderly. Additionally, capitalization of this type of human resources usually only generates low profits and it is thus difficult to afford the huge organizational costs incurred in the initial stage of organization.

Consequently, foundations for good governance can be set up in cultural and social areas with lower cost and easier access for women and the elderly, to facilitate the establishment of social organizations to reduce transaction costs. Beyond this, when conditions are more mature, it will be possible to enable vulnerable groups to help each other and coordinate with each other in the areas of production, purchasing and selling, and funding. They will be able to realize their objectives of diverting risks and stabilizing profits on the basis of comprehensive cooperation, and thus establish a basic foundation for sustainable development.

Given that the poor population usually has relatively small-scale economic activities and a low-level of commoditization, it is recommended that special institutional arrangements be put in place to ensure equal accessibility and potential benefit in the process of establishing rural community corporative organizations. Possible options could include organizing poor households to form 'mutual help teams’ and jointly input their labor, or the state providing financial and technical support to households via rural co-operatives.

3. 2.4Strengthen Risk Management for Climate Change, Policy Support and Capacity Building

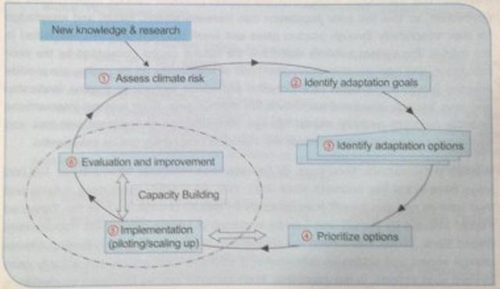

Firstly, take climate change risk analysis and evaluation as an important element in poverty alleviation planning. Take the ecologically vulnerable area as the scope of analysis and evaluation, integrating indicators such as rainfall variation, drought and flood frequency into the existing statistical system so as to provide data bases for risk evaluation.

Secondly, internalize social protection measures into the adaptation strategy, and quantify the policy support needed to realize the potential of self-initiated adaptation measures, and put this into a national budget entitled 'special fund to support climate change adaptation in poverty alleviation’. Specifically, this includes: technical support for production structure adjustment, expertise and funds for alternative livelihoods, market information support, employment information for migrant workers, techniques and network support, support to prevent and cope with natural disasters, etc.

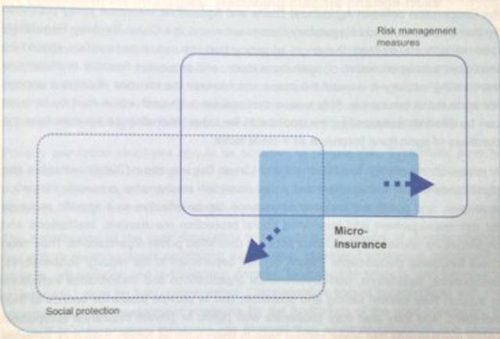

Thirdly, promote capacity building, including leadership skills, capacity of information provision, technical and funding services, and create an active local commercial environment for the development of sustainable livelihoods. In recent years, internationally, there has been considerable discussion of micro-insurance organizations and their role in protecting poor household’s assets against losses resulting from the impact of climate events. In India, for example, smallholder farming households participate in a “weather-index” insurance scheme providing compensation when the shortfall in precipitation becomes severe. Index-based insurance has also been introduced in recent years in other countries - Thailand, Mexico, Malawi and Mongolia.In each case payments are made as a result of changes in a public index triggered by climate events, such as rainfall recorded on a local rain gauge. Experiences in these countries indicate that payments can be calculated and disbursed quickly, often through the use of local microfinance organizations, without households' filing insurance claims.

Such rapid payments are useful particularly when households are poor with limited financial assets, but their assets can be pooled via co-operation.

3. 3Short-term Poverty Alleviation Policy

3. 3.1Improve Policies to Meet the Challenges of Transitional Poverty

In the near future, adjustment should begin with relevant policies aiming to benefit the transitional poor population to a greater extent than previously.

Firstly, improve the existing connections between urban and rural public service policies, in order to make preparations for a rural-urban integrated public service policy system. There are many cases of integration from which experiences can be drawn internationally. The Strategic Initiative Report on appropriate anti-poverty policies for the rural-urban transition, for example, cites a number of relevant examples, notably from the UK, USA, Germany, South Korea and Chile.

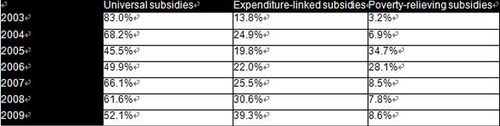

Secondly, there is a need to strengthen the poverty sensitive agricultural preferential policy as a counterpart to the current agricultural preferential policy. Building on this improvement, the Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation of the State Council should evaluate the effectiveness of poverty reduction (including that of relative poverty) through the robustness of current agricultural preferential policies and adding new initiatives. It is suggested that international donors provide technical support for the evaluation of effectiveness of these services and policies in poverty reduction.

Thirdly, on the basis of such an evaluation, new policies in poverty alleviation can be formulated, which can compensate for the'poverty alleviation deficiency’ prevalent in both universal subsidy and income-oriented agricultural preferential policies. Specific policy measures include: expanding rural medical support coverage; establishing a production support fund for small households, in particular by further developing village level pilots via the’mutual help fund’; Carrying out a comprehensive training program for vulnerable groups employed in cities; set up intervention projects for those left behind in the villages, such as on medical care for the elderly,

Finally, begin household registration reform in large and middle size cities, to promote social inclusion of rural migrant workers in cities.

3. 3.2Implement Multidimensional Poverty Intervention Projects

Launch early childhood nutrition intervention programs (e.g. early-stage children’s food supplement); full implementation of the boarding school free nutritious meal plan; providing health care services for women and children in poor areas; Integrating early childhood education as a part of the public education system and providing special financial funding for it; expansion of compulsory education from nine years to twelve years; providing conditional cash transfer payments to enable children in poor households to receive education in order to address the issue of income poverty resulting from insufficient schooling.

There is now a wealth of international experience on the use of conditional cash transfers on which China can draw, notably from the renowned Bolsa Familia Program in Brazil - currently covering almost 50 million people, or a quarter of the population, and requiring health clinic and school attendance. Similar larger-scale schemes have been implemented in other Latin American countries such as Mexico and Nicaragua. In Asia, Indonesia and Bangladesh have such programs, and Cambodia and Pakistan have pilot cash transfer schemes. Currently, Africa’s most notable Cash Transfer scheme is in Zambia, providing basic subsistence funds dependent on regular school attendance. Chapter 4 discusses these programs, also noting their limitations, particularly in relation to issues such as sustainability and improved learning outcomes. It is also crucial to enhance the rights awareness of the poor population by improving village governance.

It is recommended that the Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation (LGOP) develops a research framework for multidimensional poverty alleviation strategy, and that international development donors provide technical support to develop an indicator and monitoring/evaluation system for multidimensional poverty policies and their implementation.

3. 3.3Improve the Poverty Reduction System and Village Governance

Firstly, efficiency improvements should be made in the traditional top-down poverty alleviation system. On the one hand, it is essential to improve the structure and functioning of current village level administration, particularly the capacity building of village institutions; on the other hand, professional civil organizations are needed and farmer organizations should also be further developed, particularly in relation to their role in bridging different stakeholders. In the next poverty alleviation program, the task of building capacity for village committees should be stressed, and the development of multiple civil organizations for poverty alleviation should be supported.

Secondly, efforts should be continued to reinforce multiple inputs into villages that have completed integrated village development planning, and increase financial inputs to support their social and cultural activities, and to enhance the organizational level of rural vulnerable groups. More policies should be enacted and conducted to support and promote rural social and cultural organizations that have broad yet limited group participation, to transform them into comprehensive and multi-functional community cooperatives. Furthermore, on the basis of the development of multiple social organizations, good village governance will be achieved, which will ensure sustainability for poverty alleviation.

Thirdly, on the basis of a full consideration of funding coverage and safety, the robustness of rural financial corporations should be reinforced in the process of integrated village development and village level mutual-support collectives. Policies and mechanisms should be enacted to enable groups with limited capacity to participate in financial cooperation initiatives. Specifically, the following should be included; cancellation of policy barriers on peasant cooperative finance; enacting policies to encourage rural cooperative finance organization development; providing “seed funding” for peasant cooperative financial organization via fiscal funds. In areas with mature conditions, the establishment of cross-village economic collectives should be encouraged. It is suggested that international donors identify the development of farmer organizations in poor areas in China as an important agenda in their specific country programme, with an emphasis on supporting pilots in different areas.

3. 3.4Strengthen Policies and Measures to Improve the Ability to Adapt to Climate Change

Firstly, since basic infrastructure is crucial for improving the ability of the poor population to adapt to climate change, construction of these facilities remains an important measure. However, when building, maintaining, or improving infrastructure, more attention should be paid to ecologically vulnerable areas, integrating this with policies on relocation.

Secondly, it is suggested that the Ministry of Finance establish a “climate change risk fund” to cope with natural disasters and reduce disaster damage, and to provide support for the poor population to enhance their capacity to adapt to climate change. Taking funds from the emission tax can be a first step in the development of this fund.

Thirdly, establish micro-insurance mechanisms in areas with high climate change risk, so that when households encounter assets losses caused by the negative effects of climate change, a maximum level of compensation can be provided, and the incidence of returning to, or falling into poverty, can be reduced. It is recommended to implement small scale micro-insurance pilot projects in poor areas, with reference to international experience, and that international development organizations provide support for the necessary research on livelihood safety insurance mechanisms in China's rural areas, particularly via undertaking projects piloting community-based micro-insurance institutions.

Fourthly, it is recommended that the current ecological compensation system be reformed and a policy on the purchase of environmental services be formulated, for which international development organizations can design and implement pilot projects.

Fifthly, the agenda for improving the ability to adapt to climate change risk should be integrated into the twelfth five-year poverty alleviation plan, and its implementation and monitoring/evaluation system. Through the methods used in village participatory development planning, groups atparticular risk (from disease, accidents etc.) and groups at symbiotic risk (loss due to drought or flood) should be targeted as particular groups to diagnose, and for which feasible solutions and coping strategies can be proposed.

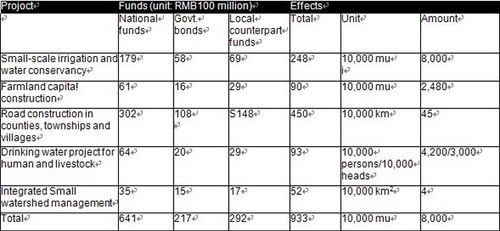

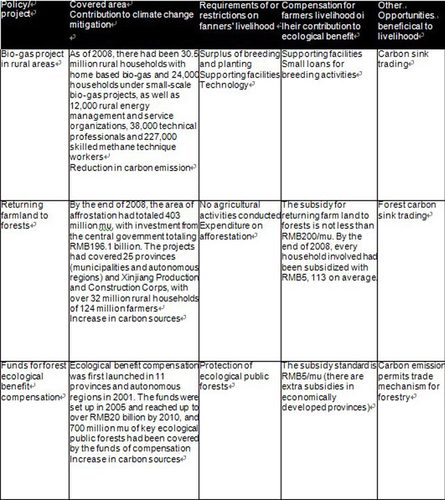

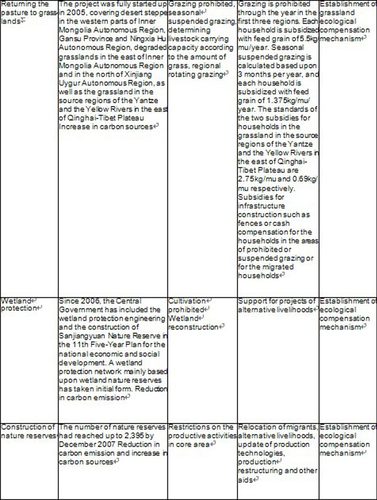

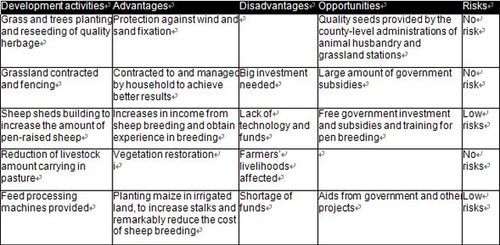

Table 1: Challenges for China’s Future Rural Poverty Reduction Strategy and Recommendations

Multi-dimensionalPoverty Measurement and Targeting

1. Introduction

1. 1The concept of multidimensional poverty in China

Multidimensional poverty is poverty caused by deficiency or lack of well-being (including social services). It reflects the poverty situation during the socioeconomic transition between the failure of original welfare mechanisms and the gradual establishment of a new welfare supply system. When a family cannot afford basic non-income welfare with its income, these results in an ever-increasing “social cost externalization" on society that ultimately is the result of conflicts in policy. Then multidimensional poverty emerges.

The concept of multidimensional poverty was first put forward in the mid-to late 1990s, and has been adopted for China’s poverty alleviation strategies and practices since the beginning of the 21st Century. The pluralism of poverty has been taken into account by the eight identifiable indicators of poor groups in the Whole-Village Poverty Alleviation Strategy and by Participatory Poverty Assessments. An empowerment mechanism has been adopted for select projects with villager participation. The China State Statistical Bureau has used the term “multi-dimensiona! poverty” in China Rural Poverty Monitoring Reports since 2007.

As China progresses from an overall “well-off" (Xiao Kang) stage to an all-around “well-off’ stage, the basic social contradiction between people’s growing material and cultural needs on the one hand, and limited social productivity on the other, is becoming increasingly acute. More specifically, as society progresses to new stages, individuals will no longer be satisfied with basic subsistence; rather, their needs will increase further.

Individual needs differ according to circumstances, such as those of endowment, employment and basic social insurance. However, fundamental rights granted to every citizen by the Constitution (including equal rights to education and health, the right to know, and the right to participation), have become a part of people’s basic needs. Many needs related to well-being cannot be purchased with income. Thus, a strict income- poverty concept does not address people's basic needs of well-being, nor can it adapt to the building of an all-round, well-off society where common progress is required to meet political, economic, social, cultural and ecological needs.

As the first poverty alleviation and development program 2001-2010 is coming to the end, we need to clarify the concept of multidimensional poverty and adopt it for the country’s new policy system. It should be clearly stated that as society advances, besides income poverty, we need to consider poverty caused by inadequate health, education, employment, etc. This means a broader concept of poverty with connotations beyond monetary aspects.

The scientific study of poverty has been undertaken for more than 100 years in China. Only a few western countries use the concept of multidimensional poverty since the welfare distribution in these countries is sufficiently well established to reach most citizens, and the extra income received by each individual is regarded as earnings. It is particularly important to introduce multidimensional poverty and related indicators in China, for the following reasons: firstly, multidimensional poverty can reveal inequalities in the supply of basic social services and the degree of poverty; secondly, since the multidimensional activities implemented in poverty reduction practice have not been formally integrated into national policy, it is important to do so in order to provide policy safeguards for poverty reduction in the new era, and thus to promote consistency between policy and activities in poverty reduction.

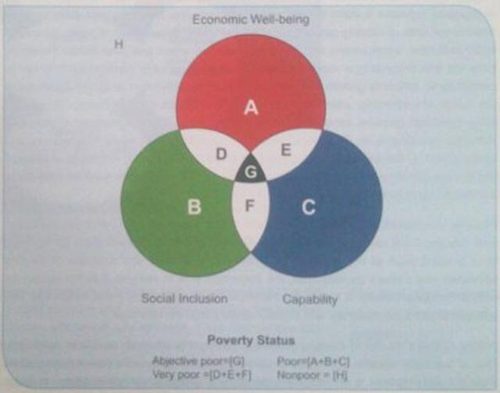

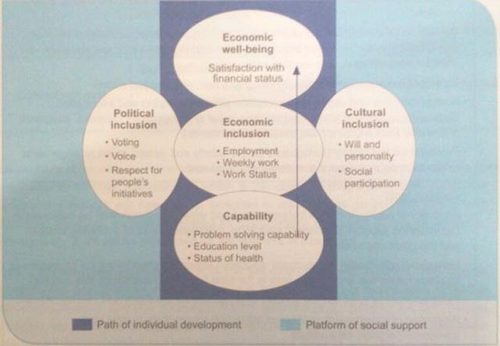

1. 2The connotation of multidimensional poverty

The concept of multidimensional poverty involves the basic needs of income necessary for people-centred development, and the realization of entitlements for the development of an all-round well-off society. The concept of multidimensional poverty has three aspects, as follows:

1)Multidimensional poverty is a socio-political concept and is not limited to the field of economics. People are often influenced by the poverty line standard proposed by mainstream economists and accustomed to considering poverty as a strictly economic issue. While formal rules in an economic system are defined and guaranteed by political systems, so political systems include variables that determine economic performance. This has been proven by the achievements in China’s poverty alleviation which have been “guided by the government with participation by the whole of society" since China’s Reform and Opening.

2)The concept of multidimensional poverty contains a strategy for the pursuit of equality. Equality means equal opportunities, and begins with equal basic conditions, access to equal processes for development, and finally equality in results that lead to common prosperity. This is a process focusing on livelihoods and development achievements that are shared by the people.

3)Well-being is usually realized through consumption, including consumption of both private and public goods. However, as public goods such as education and medical services are transformed into quasi-public goods due to inadequate supplies, or monopolised into private goods due to limited resources, a large number of ordinary people will no longer be able to afford an adequate level of social well-being, due to their limited incomes. This will give rise to a reverse wealth formation process that could further increase the numbers within the low-income or underprivileged stratum.

If no effective preventive measures are taken before these ''stratum" solidify into “classes”, a more equal society may only be realized via a “revolution”. This runs counter to the idea of building a harmonious society, Therefore, the concept of multidimensional poverty has connotations of policy sensitivity that precede the ossification of underprivileged "stratum” into such “classes”.

1. 3Why multidimensional poverty alleviation policies in China?

Based on the challenges of poverty alleviation, China’s population dynamics, and current international conditions, we view this as an opportune time for China to adopt multidimensional poverty alleviation policies.

Firstly, China has achieved world renown in the area of poverty alleviation during the last 30 years; however, the present challenges arising in poverty alleviation for a well- off society are different from problems faced during the “subsistence poverty” period, in that the previous poverty alleviation policy system has failed to meet the actual needs in the current stage. This is not purely a technical problem of targeting. This is a problem of replacing the old system with a new one that meets needs in the new stage. Additionally, there is a general institutional problem experienced by many developed countries, that underprivileged groups cannot enjoy benefits due to the lack of a clear means for testing and monitoring horizontal transfer payments for multidimensional poverty alleviation. The previously set criteria for one-dimensional poverty (that took income and consumption as leading factors) cannot reflect the actual status of poverty, and can hardly facilitate effective resource allocation or poverty monitoring for poverty alleviation. It is an arduous long-term task for China to further eliminate poverty and realize common prosperity.

Secondly, from the perspective of China’s future and the development of human wellbeing, forward-looking strategic research is needed. In the past 250 years along with the progress of industrialization, less than 1 billion of the population has been modernized, and these people are concentrated mainly in the developed countries. In the future 50 years, the world modernized population including those from China may exceed 2 billion or more; however, research must be conducted focusing on the resource and environmental problems emerging during the process of population modernization, and a feasible path must be explored for sustainable development and poverty reduction.