2011.05-Working Paper-Infrastructure The Foundation for Growth and Poverty Reduction A Synthesis

Infrastructure: The Foundation for Growth and Poverty Reduction: A Synthesis1

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

1. Introduction: Objectives and a Framework

2. Infrastructure in China’s Growth and Poverty Reduction Experience

2.1 Infrastructure: tackling the growth bottlenecks in five stages

2.2 Infrastructural Financing: Fiscal Resources and the Role of Donors

2.3 Debt and Market-Based Financing of Infrastructure

2.4 Lessons that are most relevant to Africa

3. Infrastructure and Development Partnerships in Africa

3.1 Strategies and initiatives being implemented

3.2 China’s engagement and approaches in Africa

3.3 Perspectives from Africans

3.4 Approaches by established donors

4. Going Forward: Opportunities and Challenges

Box 1. Foreign Aid in China’s Infrastructure: Volume and distribution

Box 2. China: Cases of Private Sector Participation in Infrastructure

Box 3. China’s Engagement in Africa’s Infrastructure: Commitments and Composition

Box 4. For Investors in the Extractive Industries: Five Principles

Annex 1

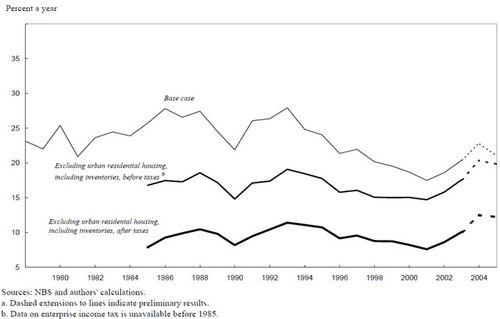

Figure 1 China: Before- and After-Tax Return to Capital, Excluding Residential Housing and Including

Inventories, 1978-2005

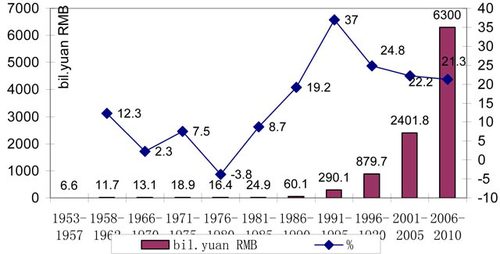

Figure 2 Investment in Fixed Assets in Transportation Sector(1953-2010): Amount and Growth Rate

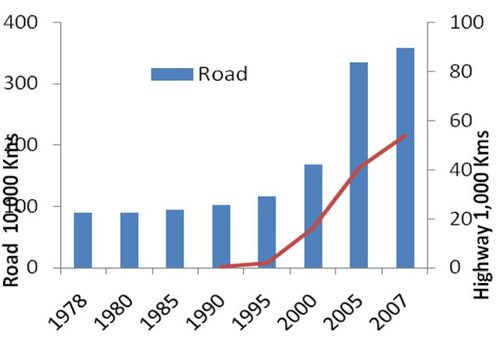

Figure 3 China’s Road Transportation

Figure 4 Growth of township roads in China 1995–2002 (km)

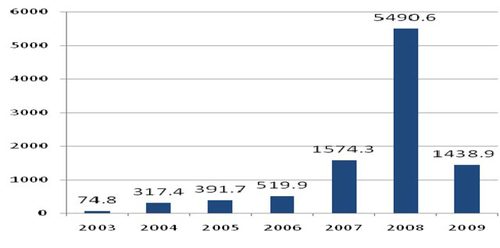

Figure 5 China’s FDI outflow to Africa, 1999-2009 USD millions

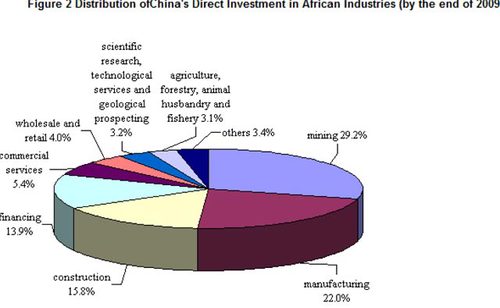

Figure 6 Composition of China’s outward direct investment in Africa

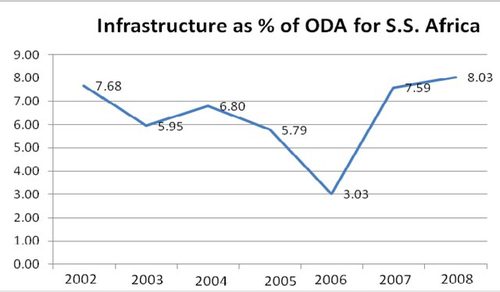

Figure 7 Infrastructure as a percentage of Official Development Aid for Sub-Saharan Africa 2002-2008

Table 1 Africa’s Infrastructure Investment Needs and Funding Gaps

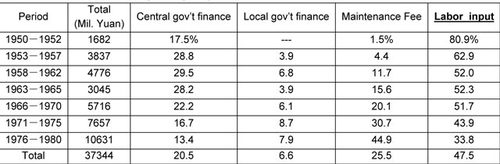

Table 2 Sources of financing for highway construction from 1950 to 1980 (%)

Table 3 Investment structure of highway construction in China (2000-2007)

Infrastructure: The Foundation for Growth and Poverty Reduction: A Synthesis

Executive Summary

In the aftermath of global financial and economic crisis, it seems that the global economy is now supported by multiple growth poles, as developing countries’shares of global export and FDI have grown rapidly. Investing in bottleneck-releasing infrastructure projects in developing countries is an important way of creating demand for capital goods, which will contribute to the global recovery as well as to sustainable and inclusive global growth. Africa, in particular, could become a growth pole if infrastructure and other constraints can be removed. (G-20 Summit)

Both China and OECD-DAC members and other development agencies have a long history of supporting Africa’s infrastructure. After years of decline, ODA directed towards infrastructure has rebounded to now

accounting for 8 percent of the total for Africa. As China is now the largest external source of infrastructure investment in Africa, it is natural to ask what lessons China can draw from this international experience, especially to accelerate economic growth and poverty reduction in Africa, and how co-operation can be strengthened.

In this sense, the third event of China-DAC Study Group on “Infrastructure: the Foundation for Growth and Poverty Reduction”was timely. This event focused on the role of infrastructure in promoting economic growth and reducing poverty by addressing three key dimensions of infrastructure development: i) ensuring sustainability– includingfinancing, maintenance and environmental impact, ii) achieving efficiency – including planning, resource

allocation and public- private partnerships (PPP), and iii) increasing impact on economic growth and poverty reduction.

It is hoped that China can serve as sources of inspiration, financing and know-how in this regard. According to China’s own development experience, infrastructure has played a major role in accelerating growth and poverty reduction. For example, after the beginning of the economic reform and opening up period:

• China's infrastructure development was initially led by rapid trade expansion, and financed by all levels of government as well as the private sector, with cost recovery principles and practices widely applied.

• The government played a leading role in strategic planning, financing infrastructure development and resolving the bottlenecks for growth, while maintaining fiscal discipline. Commercial loans, infrastructure bonds and urban development funds have been used to enforce market disciplines. National and regional economic integration was a major concern.

• International partners played a catalytic role in China’s process of learning, reforming and innovating, and initially provided substantial funding and management experience.

Infrastructure development and financing is complex and different principles apply. Infrastructure covers multiple sectors ranging from the public goods and semipublic goods, and private goods (such as extractive industries). Thus different types of infrastructure need to be financed in very different ways, sometimes by government budget and Official Development Assistance (ODA), other times by a combination of both public and private (concessional and nonconcessional) financing sources. There are different rules for international donors, and those for private sector investors engaging in PPP projects or in purely commercial deals. In particular, there is an expectation now that companies engaged in the extractive industries should follow the five internationally recognized principles (Box 4).

DAC members have moved towards greater co-ordination behind the principles of the“Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness”to strengthen country public management and accountability systems. China, to increase sustainability, is basing its co-operation around an enterprise-based approach, using both concessional and non-concessional financing, with significant and sustained involvement in management by Chinese state and private sector enterprises.

There are opportunities to bring these two approaches together in a way that can improve the collective impact of infrastructure development in Africa on growth and poverty reduction. For example, the European Infrastructure Trust Fund in particular has been using a ‘blending mechanism’, mixing grants from donors with long-term investment finance from financiers.

As the experience of China suggests, political leadership and strategic policy and planning capacity combined with pragmatic step by step adjustment to evolving needs and opportunities are important factors in building infrastructure. "Soft infrastructure", in terms of the capacity to ensure efficiency and poverty impact in project selection,

implementation, operation and maintenance is a key part of this.

African officials participating in this event hoped that all international partners, including China, could support PIDA -- the Partnership for Infrastructure Development in Africa led by the AfDB. Participants also noted that governments are increasingly focused on PPPs and are also encouraging greater private sector participation in regional infrastructure development. Participants felt that projects such as the Tanzania-Zambia Railway (TaZaRa) which were developed in conjunction with the Chinese should be replicated given their significant impact on the development of those countries involved. African officials have identified specific actions China can take in supporting the development of regional infrastructure in Africa, in particular, addressing issues related to transparency, international competitive bidding, creation of local jobs, and sustainable development.

Developing countries, China, Africa and international development partners face a host of challenges going forward. First, strengthening state capacity in Africa is the key for the continent’s economic and political renewal. Second, as the public sector faces severe budget constraints, public-private partnerships offer a promising solution to the financing needs. However, there are considerable risks associated with inefficient procurement policies and inadequate contracting arrangements. Furthermore, learning needs to be based on good evaluation on what has worked and what not. All international partners need to provide better financial and technical support on the evaluation of projects as well as assessment of their impacts. Finally, many developing countries would benefit from

greater cross-country fertilization of experiences through South-South learning, peer-reviewing, training and capacity

development, especially on infrastructure, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and EITI related issues.

1. Introduction: Objectives and A Framework

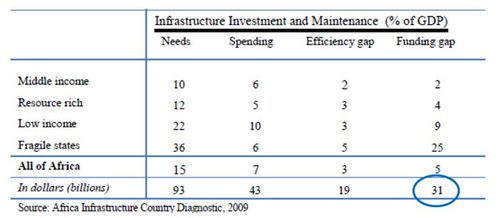

1.1 With 40 percent of the population living in landlocked countries, Africa has a major deficit in infrastructure at both the national and regional levels. Only 29 percent of households in Africa have access to electricity, 31 percent have access to improved sanitation facilities, and 60 percent have access to improved water sources. In rural areas, only 33 percent of the rural population has access to all-weather roads, as compared to 49 percent in other lowincome countries (Fay and Toman 2010). Low population density and the extremely low economic density result in high cost and low profitability of infrastructure investment. To accelerate Africa's growth performance, its investment needs in infrastructure must be addressed: annual infrastructure needs were estimated at USD 93 billion (of which one third is required for maintenance). Annual spending (domestic and foreign, public and private) is now about USD 45 billion and efficiency gains worth USD 17 billion are available. This leaves an annual funding gap of USD 31 billion (or 5 percent of GDP), mainly in the power sector. (Table 1 in Annex 1. The Infrastructure Consortium

for Africa 2010)

1.2 Since the 1960s, China has placed great importance in building infrastructure in its development cooperation with Africa, with 500 out of the 884‘turnkey’projects in Africa being in infrastructure. In the recent years,

China has intensified its development cooperation and is helping to fill this infrastructure gap in Africa. While there are inadequate official data available on China’s economic co-operation with Africa, China's total support for African infrastructure -both concessional and non-concessional has been estimated to have hovered at around USD 500 million a year in the early 2000s, rising to USD 5 billion in 2007 and USD$9 billion in 2009 (The ICA 2010; Chen 2010).

1.3. OECD-DAC members and other development agencies also have a long history of supporting Africa’s infrastructure. After years of decline, ODA directed towards infrastructure has rebounded to now account for 8 percent of the total for Africa. In 2007 and 2008, bilateral and multilateral donors disbursed a total of approximately USD 4

billion of official development assistance (ODA) to support economic infrastructure development in Africa (according to OECD/DAC data). Africa’s infrastructure and its research and development capacity have

also been influenced by the donor

community.

1.4. Given that China is now the largest external source of infrastructure investment in Africa, it is natural to ask what lessons China can draw from this international experience, especially to accelerate economic growth and poverty reduction in Africa, and how co-operation can be strengthened. In this sense, the third event of China-DAC Study Group on“Infrastructure: the Foundation for Growth and Poverty Reduction” was timely. This event focused on the role of infrastructure in promoting economic growth and reducing poverty by addressing three key dimensions

of infrastructure development: i) ensuring sustainability – including financing, maintenance and environmental impact, ii) achieving efficiency – including planning, resource allocation and public-private partnerships (PPP), and iii) increasing impact on economic growth and poverty reduction – including procurement approaches, linkages into the local economy and involving poor people in decision-making processes.

1.5 More specifically, the event on Infrastructure has:

• Reviewed the development strategies, policies and instruments used in the three dimensions of infrastructure – ensuring sustainability, achieving efficiency and increasing impact; focusing on the practices that are most relevant for countries in Africa.

• Examined the increasing role of China’s engagement in Africa’s infrastructure and its potential impact

and compared this with the lessons learnt by international donors.

• Explored the opportunities, means and benefits from better co-operation on support to infrastructure between

China, DAC donors and African countries.

A Framework

1.6 Defining infrastructure. In this report, infrastructure covers social sector infrastructure such as schools and health facilities, as well as economic infrastructure such as transport, irrigation, drinking water and sanitation, and to a lesser extent, energy, and information and communication technology (ICT). Infrastructure also involves both physical facilities (roads, water connections, and health clinics) and services (transport services, energy and water supply) and involves investment, management, maintenance, capacity building, regulations and policy making, which is usually referred to as “soft infrastructure”. In addition, it can span countries, borders and regions which, in this report, will be referred to as “cross border infrastructure” (OECD 2006).

1.7 A framework for analysis. The China-DAC Study Group focuses mainly on those infrastructural sectors that belong to the category of public- and semi-public goods,2 i.e. those that cannot be supplied by the private sector using purely market instruments. In a sense our scope encompasses both social and economic infrastructure, as well as the hardware and software aspects. Energy and mining and ICT sectors are not our main focus, as they

are generally regarded as goods and services that can be provided, mostly, by the private sector.

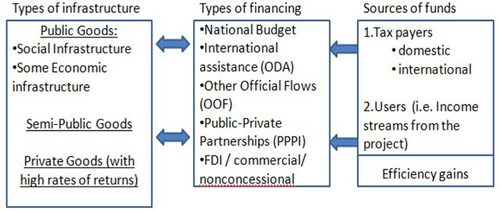

1.8 Modalities for infrastructure financing. Infrastructure investments are generally lumpy and costly and thus require significant finance. What is not clear, however, is how to link the types of infrastructure with the financing modalities. Exhibit 1 below illustrates that there is a relationship between the types of social or economic infrastructure, and the financing options. Specifically,

• Most social infrastructures such as sanitation and preventive health facilities, being public goods, have

higher positive externality but low private return, and may have to be financed by the government fiscal budget, official development assistance (ODA) such as grants and no-interest long-term loans and concessional loans. They will be

undersupplied if not financed by the governments or ODA.

• Many economic infrastructure, such as highways, rail and power generation, is within the category of semi-public goods, and they have a higher probability of cost-recovery. The “users pay” principle can be applied for cost-recovery, and thus they can be financed by mixtures of concessional and non-concessional loans, Other Official Flows (OOF), and Public-Private Partnership (PPP) approaches.

• On the other hand, energy, mining and telecommunication sectors are commercially viable with high rates

of return, and thus can be financed by commercial loans, FDI, equity investment, commodity-backed loans and other market instruments.

1.9 This framework is useful to help understand the current practices of combining trade, aid and (public and private) investment in infrastructural development. Indeed, all three approaches -trade, aid and investment- and many instruments are needed for meeting Africa’s urgent need for infrastructure.

Exhibit 1. Modalities for Infrastructural Financing and the Nature of Infrastructure: public or semipublic goods?

Source: Yan Wang’s revision based on Fay and Toman, 2010, p. 352.

2. Infrastructure in China’s growth and poverty reduction

2.0 Numerous studies have shown that infrastructure provides the basic foundation for economic growth through propelling productivity, facilitating trade and reducing transaction costs. Careful review of the literature found broad agreement with the idea that infrastructure generally matters for growth and productivity, and some analysts

suggest its impact seems higher at lower levels of income.3 Increased infrastructure is estimated to have contributed an additional 2-2.5 percentage points to per capita income growth during the early 2000s in Latin America (Calderon and Serven, 2010). Good infrastructure is also found to facilitate international integration (Dollar et al. 2006).

2.1 Infrastructure appears to be particularly important for poor developing countries. In a sample of poor countries (Bangladesh, China, Ethiopia, and Pakistan), infrastructure has positive effects for productivity, factor returns, and international integration. According to Antonio Estache, the rates of return from Infrastructure could range from 20 percent to 200 percent (Estache, 2006). A recent study found that in China the aggregate rate of return to capital averaged 25 percent during 1978-1993, fell during 1993-1998, and has become flat at roughly 20 percent since 1998 (Bai, Hseih and Qian 2006) (see Figure 1). This point is particularly relevant to Africa where the infrastructure gaps are bigger and potential shadow prices are 3 See Romp and de Haan 2005, Calderon and

Serven 2010, Briceno-Garmendia, Estache and Shafik 2004. higher. Or in other words, infrastructure investment seems to have higher returns in countries with poorer infrastructure (Collin L.Xu 2010).

2.1 Infrastructure: tackling the growth bottlenecks in five stages

2.1.0 Infrastructure provides the foundation for economic and productivity growth, as well as the basic conditions for reducing the non-income side of poverty, through providing water, sanitation, shelter and health and education services. The Chinese Government has always given priority to infrastructure development, which was motivated, first by the strong desire for industrialization in the pre-reform era, and then, propelled by the export-promotion strategy in the post-reform era.

2.1.1 Stage 1 between 1954 and 1977, China concentrated the bulk of its industrialization effort on heavy industries, promoting rapid growth in industries such as coal, oil and power. At the end of 1970s, over 50 percent of its exports were in the primary sectors including crude oil, crude coal, and agricultural products. Many rural

water and infrastructure projects were built at low cost with significant rural labor contribution through “work for food” programs. In the transportation sector, the national highway construction and administration authority was released to local government agencies from the late 1950s, while the Central Government focused on railway construction. Although the state investment in highway was small during the period, local government was

eager to construct rural and urban roads. From 1958 to 1980, the length of roads increased 2.5 times, and the contribution of local labor was quite significant at early stages, but declining from around 60 percent in the 1950s to 30 percent in the 1980s (Table 2, Guo 2009). This shows that China was forced to use cheap labor in building infrastructure due to inadequate financial resource. This strategy can be summarized as “using labor substituting for capital”. (Li Xiaoyun)

2.1.2 In Stage 2, from 1978 to 1989, China started the reform and opening up process, particularly through establishing Special Economic Zones in the coastal areas. Trade started to expand, and infrastructure building

was financed by international partners and foreign investment in building ports and roads to facilitate exports. International competitive bidding was introduced to China in 1984 through the World Bank’s Lubuge hydropower project, creating a “Lubuge shock” (People’s Daily 1984, Lu and Wang 2004). State-owned companies were

separated from the government ministries and had to compete with international market participants. In addition, an initial wave of fiscal decentralization provided local governments with incentives to develop local infrastructure.

2.1.3 Stage 3 from 1990 to 2002 was a period of addressing growth bottlenecks. Rapid trade expansion led to bottlenecks in power and transportation in the coastal areas. Traffic congestion and power shortage frequently occurred. Government financing of basic infrastructure rose rapidly in such sectors as water supply, power

generation, energy, transport, post and telecommunication as well as raw materials. In particular, public investment in transport infrastructure grew at a rate of 25 to 30 percent in the 1990s, reaching a new peak after the 1997 Asian financial crisis (See Figure 2). Foreign investment and BOT were introduced to infrastructure, as in the cases

of Laibin B Power project and several toll roads and toll bridges (see Box 2). A modern construction sector emerged and grew to be competitive through learning by doing and international competitive bidding, first in China and later, elsewhere.

2.1.4 Stage 4, from 2003 to 2008, was one of rapid and comprehensive development in rural and urban infrastructure in China. After the Asian Financial crisis, the government launched the strategy of “Go West”, and

enhanced infrastructure development in the western regions. The development of expressways has been particularly remarkable (figure 3), with the total length increasing from 147 kilometers in 1988 to over 60,000 kilometers in 2008 (Guo 2009). The rural highway network also expanded considerably. By 2009, over 98 percent of the villages could be reached by roads, an increase from 80 percent in 1995 (Zheng Wenkai; Zhang Lixiu).

2.1.5 Stage 5 is associated with the government’s strategy to intensify both domestic and overseas investment in the pre- and post-crisis era. Between 2006-2009, China doubled its development cooperation in Africa. Meanwhile, Chinese parastatal companies have become internationally competitive with the government’s support to “Go global”. In 2009, China’s outward direct investment in Africa reached $1.44 billion USD, in which non-financial direct investment increased by 55.4 percent as compared to 2008. In addition, the value of China’s new project contracts in Africa reached $43.6 billion, an 11 percent increase over 2008 (CAITEC 2010, page 10). Domestically, China implemented a RMB 4 trillion stimulus package after the global financial crisis, of which RMB 1000 billion was used for post-disaster reconstruction and RMB 1500 billion for infrastructure investment in such sectors as general transport, urban transport and high-speed rail.

2.2 Infrastructural Financing: Fiscal Resources and the Role of Donors

2.2.1 There are two major channels for infrastructure financing: (i) direct budget investment from fiscal resources, (ii) market-based financing including borrowing and PPPI. On the first aspect, the Chinese Government’s prudent and proactive fiscal policy played an important role in infrastructure development. China’s fiscal system in the last thirty years has been in the process of transition from the planning model of “financing industrialization” to the market model of providing public goods and services.

2.2.2 First, the government has been maintaining a prudent fiscal policy and following the principle of “planning projects according to affordability” (“liangli erxing”). Prior to 1978, China practiced a “unified collection and allocation of funds by the state (tongshou tongzhi)” in which fiscal power was highly concentrated in the center and there was no foreign debt. From 1978, the government started to borrow from foreign governments and investors but followed a strict fiscal discipline, and never borrowed heavily for infrastructure investment (total

foreign aid has never exceeded 3 percent of GDP).

2.2.3 Second, fiscal decentralization since 1980s played a critical role in providing incentives for provincial and local government for promoting growth. Decentralization proceeded in two waves:

• From 1980 to 1993, China implemented the “fiscal decentralization-Chinese style”method / process, which was essentially a fiscal contracting system where provincial governments began to retain a share of revenue for the development of local economies. The Central Government’s share of fiscal revenues fell from 34.8 percent in the 1980s to 22 percent in 1992.

• The second wave started in 1994 when a/the tax assignment system was introduced, and further enhanced incentives for local governments to promote growth by investing in infrastructure. The overall fiscal stance has improved since 1994, with the overall fiscal envelop reaching nearly 25 percent of GDP. Interestingly, the taxes

assigned to sub-national government account for part of the fastest-growing major revenue sources: i.e. 100 percent of the personal income tax, most of the company income tax, and 25 percent of value-added tax. Thus, the local

government’s fiscal autonomy has been enhanced over the years (Su and Zhao 2006).

2.2.4 In the area of expenditure policy, several noteworthy features are evident: First, the share of capital construction fell from more than 12.5 percent of GDP in 1978 to 2.5 percent in 2004 (or, from 40 percent of total government expenditure to 12 percent in 2004) (Hussain and Stern 2007). Second, the share of culture, education, and health expenditure rose steadily in the 1980s but declined in the mid- 1990s. Third, there is a clear division of

labor between the central and local governments on who finances what, and who has the ownership and responsibility for completing the projects and for postcompletion maintenance. For example, provincial highways are financed mainly by the provincial governments, county roads mainly by county governments, and village roads by the communities and through participatory approaches (CDD projects, or targeted poverty projects).4 (Zhang Lixiu)

2.2.5 Specifically, in highway construction, the share of state financing from the fiscal budget has been declining, with a large proportion financed by loans from the state owned banks and enterprise raised funds (including those from income streams). Rural road improvements were also integrated with major highway projects,

and implemented with external development assistance. In 2007, national highway construction was financed from three major sources: 14 percent from the state budget (including revenues from the vehicle tax), 40 percent from commercial loans, and the rest, from funds raised locally and by enterprises including user fees (Table 5, Guo 2009).

2.2.6 Urban infrastructure has been financed from multiple sources. Since urban capital construction is a local (subprovincial) government responsibility, the majority of spending is done by local governments. Before 1990, the main funding sources for urban infrastructure construction came from the local urban maintenance and

construction tax and from public utility surcharges. From 1991 to 2001, the proportion of total urban infrastructure

construction financed by budgetary funds decreased from 50 percent to 29 percent, and the decline continued thereafter. By 2001, more than 60 percent of the cities in China had infrastructure loans from the state owned banks, accounting for 30 percent of the total (Su and Zhao 2006, p38-39). The proportion of enterprise funding including user fees rose in recent years.

2.2.7 Roles of International Partners. Among multilateral and bilateral donors, the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and Japan have contributed the largest shares in infrastructure, and all international partners

served as important catalysts for reform and services in poor regions. This however is beyond the scope of this report. capacity development.

• The World Bank has introduced international best practices in project management and supported infrastructure with both lending projects and capacity building programs. The 88 transport project portfolio accounts for 33% of total WB lending in the last thirty years (Ministry of Finance 2010). The Bank has also supported a training

network of project management which was scaled up by national learning program of over 100 universities with trainees working in many construction companies which have grown to become competitive (Lu and Wang 2004). Knowledge combined with projects has supported China’s modernization as well as growth and poverty reduction

(Liu Zhi, WB).

• The ADB has been working in the areas of regional cooperation frameworks, such as the Greater Mekong River Subregional program (GMC), and Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) economic corridors. In addition, ADB has also worked in highways and rural roads in China’s western regions as well as Technical

Assistance (Solbel, AsDB)

• Japan has shared its own development experiences on comprehensive national development plans, sustainable urban transport development, and the concept of“megalopolis”. This includes both providing aid (grant and concessional loans) and knowledge and advice (Kitano, JICA).

• The EU started to provide support to China in 1984, first focusing on agriculture and poverty reduction

prior to 1995. Later it is expanded to strengthening dialogue and cooperation with relevant ministries to provide aid and intelligence transfer to China. So far, EU’s aid to China has reached 700 million euros in total and supported some 70 projects in agriculture, energy, education, health, trade, environment protection, justice and government administration. (EU 2010)

2.2.8 China has also benefited from large amount of international loans (both concessional and non-concessional) in infrastructure. According to the NDRC, these foreign loans have, in general, i) alleviated growth bottlenecks in energy, transportation, and urban infrastructure at a time when China faced large financing gaps; ii) introduced international best practices and approaches in energy, urban and transport planning, investment and project management; and iii) promoted market oriented reforms in each sector, improved investment climate, and

facilitated productivity growth and efficiency. (NDRC 2009)

Box 1. Official Development Aid (ODA) and Foreign Loans in China’s Infrastructure

2.3 Debt and Market-Based Financing of Infrastructure

2.3.1 Over the thirty years of marketoriented reforms, China has gained considerable experience and learned

lessons in building sustainable infrastructure using debt instruments, commercial approaches and active private sector participation (PPI), in part, through learning from international partners and investors.

2.3.2 First, as a national policy, the government has encouraged the banking sector to finance infrastructure investment, especially in highway construction and urban infrastructure. In this way, the government has hoped to impose market discipline since the bank loans must be repaid (after the banking sector reforms). Second, the Central Government has also issued infrastructure bonds and passed the proceeds to provincial and local governments as a blend of onlending and grants. From 1998 to 2004, China issued long-term construction national

debt of RMB 910 billion, of which RMB131.7 billion (roughly US$16 billion) was for urban infrastructure financing (Su and Zhao 2006). All of these loans and bonds are partially backed by the income streams generated by infrastructural services (such as toll fees from highways and tariff revenue from electricity). Local governments often need to provide guarantee for the funding gaps during the operation and for the maintenance of the infrastructure. There is however, always clear ownership of the specific infrastructure as well as those who are responsible for the maintenance and sustainability.

2.3.3 Third, the “users pay” principle is well applied in China and “cost recovery” can reach as high as 30-40 percent of total cost in some subsectors. The cost recovery approach means that prices of infrastructure services must be allowed to be market determined or set at levels sufficient to finance the capital cost as well as operations and maintenance, which is critical for efficiency and sustainability. This approach has imposed market disciplines to the owners/contractors, allowed private participation, and enhanced efficiency. New evidence shows that in 2008, roughly 40 percent of the urban infrastructure came from fiscal sources (including land revenue), 30 percent from bank loans, and 29 percent from the enterprises (based on income streams such as fees and charges). Only 1 percent was from foreign investment and bonds. (Qin Hong, Center for Urban and Rural Development, 2010).

2.3.4 Fourth, private sector participation in infrastructure (PPI) in China has taken various forms and stages. Rapid economic growth in the 1980s led to an immense demand for basic infrastructure like roads,ports and power generation in the early 1990s. Road and power commanded the top priority. The Chinese Government was eager to grant favorable concessions to attract foreign investment and piloted build-operatetransfer (BOT) projects since 1996. Many different varieties of BOT approaches were invented and applied in China (see Box 2 for examples). In the period between 1998 and 2004, BOT or PPI projects declined in part due to large issues of infrastructure bond, the rising land–lease revenues, as well as the rising Urban Development and Investment Companies (UDICs). Recently, as the Central Government is tightening the control of local investment platforms leading to mounting debt, the BOT approach has been on the rise.

Box 2. China: Cases of Private Sector Participation in Infrastructure (PPI)

In the early 1990s, rapid trade expansion and growth created growth bottlenecks in roads and power, especially in the coastal regions next to the special economic zones. The potential rates of return in infrastructure were high. At the proposal of famous Hong Kong engineer and developer Gordon Wu, the first PPI project was approved in time.

2.4. Key Elements that are most relevant to Africa

2.4.1 Since most African countries are market economies, the most relevant features of China’s experiences are those related to market-based principles and instruments for infrastructure development, but not those with special features of a transitional economy. In addition, private participation in infrastructure has increased steadily since the 1990s, at an average of 13 percent a year. After the financial crisis however, PPI has becoming more important in Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia, reaching to over 2 percent of GDP (Fay and Foam 2010, page 349).

1. Infrastructure has been the foundation for China’s rapid growth and poverty reduction, especially after the economic reforms and opening up. Before the reforms the government invested heavily in infrastructure and there was welfare improvement for citizens. However, the most rapid poverty impact was seen after the economic reforms

since 1978. Since China was a capital scarce country at that time, the financing mechanism was one of “using cheap labor to substitute for capital”.

2. Economic infrastructure development should be driven by demand from trade, the private sector and the

market. In China, large investment occurred in the mid-1990s after the expansion of trade that exerted pressure on power and transport infrastructure. The government then invested to overcome the growth bottlenecks. It was openness in trade leading to infrastructure investment, not vice versa. National and regional economic integration was a major concern which motivated the investment.

3. The government has played a leading role in strategic planning, financing infrastructure development and resolving the bottlenecks for growth, while maintaining fiscal discipline. The government did not borrow from external partners heavily for infrastructure, but encouraged FDI and domestic (state and private) enterprises to participate. Investment climate was improved; laws and regulations were put in place so that debt financing and PPI was possible. Government spending on public goods such as rural water, sanitation, preventive health, primary education, and disaster prevention has been increasing in recent yearsstrengthening the impact on the poor.

4. Economic infrastructure in China has been financed by fiscal resources and user fees, as well as private

sector participation (PPI). User fees and cost recovery principles are widely applied. Efficiency is improved and market disciplines imposed because of reforms to separate enterprises with government functions, having clear

ownership and division of labor, and enforcing hard budget constraints. The impact on the poor is enhanced through support to rural infrastructure via targeted and participatory community driven development programs.

5. International partners served a catalytic role in China’s process of learning, reforming and innovating,

and initially provided substantial funding and management experience. Through mutual learning and experience sharing, China has gained access to advanced knowledge about project financing, managing, international competitive bidding, and social and environment assessments, as well as other procurement regulations. However,

there is a need to build capacity on bundling green technology with infrastructure, conducting better social and environmental assessment, and better evaluation and impact assessment.

No-so-positive Lessons

2.4.2 On the other hand, China was not successful in weeding out “white elephant” projects, and some

investments were wasteful with low efficiency and environmentally unsustainable. There is heated debate on

whether China has overinvested in some type of infrastructure and underinvested in social and environmental infrastructure. Some studies have shown that in recent years, the efficiency or rates of return from infrastructure has been declining (Li Zhigang 2010). Although there are mechanisms to weed out bad projects- including feasibility

studies, project appraisal and approval processes, due-diligence and fiduciary reviews by banks, “white elephant” projects have appeared in many sectors and places. Other studies (i.e. Fan and Chan-Kang 2005) also find China gave too much priority to high-quality roads such as expressways, though the benefit–cost ratios for lowerquality roads (mostly rural) could be four times higher than those for high-quality roads. In October 2010, a report by Chinese Academy of Sciences warned against “the danger of over-investing in certain type of transport infrastructure which is ‘ahead of its time’”. (CAS 2010)

Land based financing and sub-national debt issues

2.4.3 After years of market reform in China, the economic value of land is widely understood, and the conversion of land leasing rights or land development right into infrastructure financing is widely practiced. First, it is well established in theory that landleasing rights can be separated from land ownership rights. However, as the land

tenure system in China is not clearly defined and land market is not well developed, laws and regulations are not sufficiently clear to guide land transfer and price determination. Farmers are not always sufficiently compensated, and the risk of corruption is high. 5 This is an area where African countries need to be cautious, as good governance and transparency is critical for any development. Second, many Urban Development and Investment Companies

(UDICs) were established in China at the end of 1990s or later. Profitable and nonprofitable urban infrastructures in a city are bundled to be managed by one single state owned enterprise whose roles are heatedly debated. Some of the local financing platforms have behaved irregularly and led to huge sub-national debt. The State Council has recently put a hold on some of these illegal behaviors of the UDICs.

3. Infrastructure and development partnerships in Africa

3.0 Infrastructure has contributed to over half of Africa’s improved growth performance, but still African countries lag behind their peers in the developing world. The differences are particularly large for paved roads, telephone main lines, and power generation (Foster 2010). In all three areas, China has been helping to fill in the

significant gaps.

3.1 Strategies and Initiatives being Implemented

3.1.1. The issue of continental infrastructure development has regularly featured in the annual deliberations of the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union Commission). As a result of these continental wide deliberations, several initiatives have been carried out. Among them:

• NEPAD: One of NEPAD’s objectives is to promote infrastructure development as a driving force for Africa’s regional integration. Thus in 2002, NEPAD formulated a‘Short-Term Action Plan’(STAP) in the area of infrastructure. The initiatives of the RECs and sector organizations constitute the basis of this Action Plan. The Action Plan was soon followed by the formulation of a‘Medium to Long-term Strategic Framework’to articulate policies and strategies.

• African Union Initiatives: The AU Commission, the AfDB and the NEPAD Secretariat established a coordination mechanism for the development of infrastructure in Africa. During the last annual meeting of the African Union Commission, which took place last July 2010 in Kampala, the AU unveiled the Programme for Infrastructure

Development in Africa (PIDA). The PIDA program is designed as a successor to the NEPAD Medium to Long Term Strategic Framework. It brings together and merges various continental infrastructure initiatives, such as the NEPAD Short Term Action Plan and the Medium to Long Term Strategic Framework, as well as the AU Infrastructure Master Plans into one coherent program for the entire continent, covering all four key sectors: Transport, Energy, Trans-boundary Water, and ICT. It will also provide the much-needed framework for engagement with Africa’s development partners interested in supporting regional and continental infrastructure. (Cheru 2010)

3.2 China’s Aid, Trade and Investment Strategy in Africa’s Infrastructure: Different Modalities6

3.2.1. China’s engagement in Africa’s infrastructure is multi-faced, with several modalities serving different needs in different sectors. Chinese government agencies and parastatal companies serve mostly as investors, financiers, service providers and suppliers, and engineering and construction contractors, and to a lesser extent, as

development partners/donors. This is because the extent of concession in their infrastructure projects is nontransparent, and perhaps lower than that required by the OECD-DAC standard (requiring a grant element of 25 percent).

3.2.2 By the end of 2009, China had provided assistance for the construction of over 500 infrastructure projects in Africa, including the 1,860-km-long Tanzania- Zambia railway, the Belet Uen-Burao Highway in Somalia, the Friendship Harbor in Mauritania, the Mashta al Anad-Ben Jarw Canal in Tunisia, and The Convention Center of the African Union (State Council White Paper 2010).

3.2.3 Total commitment in infrastructure. Through grants, concessional loans, export credit, the 6 This part is based on Chuan Chen 2010: a background paper for the China-DAC Study Group’s third event on infrastructure.

‘Angola mode’, and foreign direct investment (FDI), Chinese infrastructure financing commitment in Africa has been increasing exponentially during the past decade. The confirmed amount reached 6 billion US dollars in 2009. The total Chinese financing commitment in African infrastructure development between 2001 and 2009 is in the order of US$ 14 billion. (Chen 2010). According to the State Council White Paper,“From 2007 to 2009, China provided US$5 billion of preferential loans and preferential export buyer's credit to Africa. It has also promised to provide US$10 billion of preferential loans to Africa from 2010 to 2012. These loans are to be used to finance some of the big projects under construction, such as an airport in Mauritius, housing in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea and the Bui Hydropower Station in Ghana” (State Council 2010, part III, page 5)

3.2.4 Allocation of the investment: During the same period, most Chinese financing commitment went to the electricity, ICT and transport sectors. Electricity projects alone account for 30 percent of Chinese financed projects by number, and 50 percent by value, effectively meeting the urgent demand for electricity in Africa. Chinese financing commitment in this sector has been steadily increasing. Around 36 percent of Chinese financing commitment went to 11 out of the 16 landlocked African countries and about 64 percent went to low income economies. Rehabilitation projects account for 18 percent of the Chinese financed projects. Quite a few rural and regional infrastructure projects were financed and constructed by Chinese parties. Chinese construction companies and infrastructure developers' entry into the equity project market of Africa is still at its initial stage, but they consider it to be a high-potential market. (Chen 2010)

3.2.5 Trade in Services - Chinese companies as contractors. With the management and engineering capacities to deliver and building infrastructure projects at low cost, Chinese AEC contractors have started to dominate the African markets in certain sectors. They are supported by the strong equipment and material production

industries in China and win most of their jobs in Africa through competitive bidding. It is noteworthy that Chinese AEC contractors are taking more 'permanent' market entry modes in Africa, seeking a long term presence and opportunities for development. This long term perspective is also reflected in three aspects: 1) increasing localization

level; 2) more investment in training local employees; and 3) improved awareness of their social responsibilities, which to some extent mitigate the effects of inequality in infrastructure implementation processes (Chen 2010). In 2009, “the value of China’s new project contracts in Africa reached $43.6 billion, an 11 percent increase over

2008. Those projects achieved a business turnover of $28.1 billion, up 42% year-onyear”(CAITEC 2010, page 10).

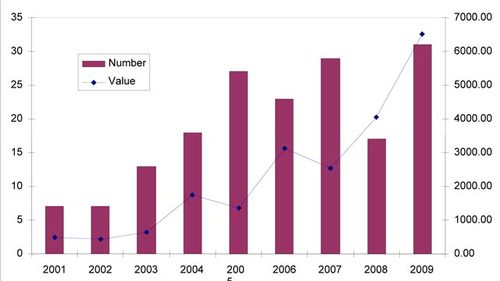

Box 2: China’s Engagement in Africa’s Infrastructure: Commitment and Composition

According to the World Bank-PPIAF Chinese projects database (2010), the total Chinese financing commitment in African infrastructure development between 2001 and 2009 is in the order of US$ 14.2 billion. The confirmed amount was estimated at 6 billion US dollars in 2009. This is however a conservative estimate, because of the limitation of the methodology to develop the Database. Given that the annual number of projects fluctuated during the past four years, the average size of Chinese financing commitment per project has been skyrocketing, indicating Chinese financiers' interest and capacity in financing larger projects. See Box Figure 1.

3.2.6. China’s Outward Direct Investment in Africa. Since 2000, China’s direct investment in Africa has been growing exponentially, increasing from a few hundred million to a cumulated amount of US$9.33 billion by the end of 2009. The investment is allocated to 49 African countries and most of which is in South Africa, Nigeria, Zambia, Sudan, Algeria, and Egypt, covering mining, financing, manufacturing, construction, tourism, agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry and fisheries. The forms of investment are diverse, including sole proprietorship, and joint ventures, as well as merger and acquisition, and joint venture with third-country enterprises for resource development. And investors range from the State-owned large and medium-sized enterprises, private enterprises and individuals. Figure 6 in Annex 1 shows the composition of China’s direct investment inAfrica by sector.

3.2.7. Special Economic and Trade Zones and FDI. China has been using a strategy of building overseas economic and trade cooperation zones to facilitate Chinese enterprises “going abroad”. Six economic and trade cooperation zones are being built in Zambia, Mauritius, Nigeria, Egypt and Ethiopia, with US$250 million in infrastructure construction. It is worth noting that investment in infrastructure in the zones is closely related to enterprise /cluster development in manufacturing sectors. The Special Economic Zone represents a“bundling”of public goods including policies, regulations, public services such as one-stop-shop, as well as roads, electricity,

water and sewage, and physical plants and housing to facilitate trade and private investment. In Chinese idioms, this is called“building the nest and the phoenix will come”(zhuchao yinfeng). Eventually, it is hoped that clusters of enterprises will be formed in certain industries where the country has a comparative advantage. This hope is not

entirely unfounded based on China’s own experiences in Yiwu, Zhejiang and other SEZs.

3.3 Perspectives of Africans: Feedback on China’s Support to Infrastructure

3.3.1 African feedback is based on the GDLN consultation which included representatives from China, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Zambia, South Africa, and the World Bank. It was held on September 7, 2010 through video conference links with each country. High level government officials who attended the consultation were generally optimistic about China’s role in infrastructure development in Africa, and felt that the challenges were well articulated and were not beyond the scope of governments and private sector to address (ACET 2010b).

3.3.2 Overall, African officials welcome Chinese engagement in African infrastructure development both as an

example of good practice and a source of financing and capacity building. They highlighted 3 areas where Africa could particularly leverage assistance from China for a win-win partnership; a) cost recovery and private sector participation – learning from the experience of Chinese government funding at different levels coupled with

project finance from private entities. b) regional integration – with clearly articulated priorities from the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and NEPAD, China can focus its investment, development and private sector involvement in Africa towards supporting regionally integrated infrastructure development. c) modalities of channeling Chinese funds and aid effectiveness – improve transparency, competitiveness, sustainability and harmonization of aid.

3.3.3 Key obstacles for investment in African infrastructure were identified by participants, including: i) a perception that there is too much risk in the African infrastructure development space to encourage participation; ii) a perception that African indigenous entrepreneurs lack the capacity or credibility to execute large scale infrastructure projects; and iii) the lack of a strong government role and long term planning is a drawback. Governments need

to play a more central role by providing seed capital for infrastructure projects and by undertaking long-term planning of infrastructure development. China’s central government has been critical in the development of infrastructure for growth and poverty alleviation; the same approach will need to be applied in African countries. The lack of a well developed fiscal and monetary system in African countries restricts the ability to launch national borrowing. Thus, for

small scale community based infrastructure development, one of the approaches could be to fully utilize local labor as partial substitutes for capital.

3.3.4 Participants of the GDLN consultation expressed concern about the effectiveness of aid from China and how to ensure that viability of projects is thoroughly assessed prior to their implementation. It is realized that African

countries themselves must analyze the economic benefits of projects prior to implementation. Host countries must engage in cost-benefit analysis and robust planning, with adequate consultation and participation of stakeholders to ensure sustainability. In particular there were concerns over:

•Limited participation of Chinese firms in Public Private Partnerships. On issues of bidding for contracts and

financing of Chinese infrastructure investments, participants expressed concern about the lack of transparency in bidding: project costs are defined by Chinese terms, and bidding processes are always limited to Chinese companies. Participants expressed concern about risk guarantees in order to encourage greater private sector

partnership. The discussant indicated that The World Bank, through its affiliate MIGA provides risk guarantees to firms operating in high risk countries.

•The relative concentration of China’s projects in four large countries, and selection of sectors-- whether these projects are in line with the country’s priority for growth and poverty reduction, (Onjala, Kenya), whether

there are some “white elephant” projects, and whether these projects have impact on efficiency, sustainability and poverty reduction(Maswana, JICA Institute).

•The poor quality of performance of some Chinese contractors. They noted, however, the competitive pressures introduced into African local markets are improving local work ethics and increasing entrepreneurship. Nonetheless, strengthening and tightening regulations to ensure that contractors adhere to certain labor, quality and environmental standards will have a marked impact on the sustainability of infrastructure development on the continent.

•Participants agreed that increasing the amount of un-tied support from China and the liberalization of Chinese contracts/tender offers would also go a long way in increasing the development benefits from Chinese projects.

3.3.5 Regional infrastructure development. Participants expressed concern about the limited interest of Chinese firms in regional projects. Some suggested that this might be due to lack of coherence and harmonization

among the individual countries involved. Participants indicated that it is incumbent upon the individual countries involved to take the lead role in managing and harmonizing their systems and procedures to attract greater Chinese participation. In addition, the need for regional projects was strongly emphasized by participants. They indicated

that governments, Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and NEPAD need to focus more on attracting financing for regional projects.

3.3.6 African participants agreed that China has a significant role to play in increasing regional infrastructure development in Africa, but that this must be undertaken with consideration for the existing challenges to cross-border infrastructure development, such as, limited bankable projects; capacity constraints, over-emphasis on national programs, and fragmentation of donor financing. In particular, the absence of harmonized procedures and regulations is a key challenge. Customs, tax procedures and obligations across borders vary significantly and they limit the development of regional infrastructure projects. This is complicated by the fact that many countries belong to multiple regional bodies often constraining full integration due to bureaucratic roadblocks. (Muradzikwa, DBSA)

3.4 Approaches by Established Donors

3.4.0 Following the Gleneagles Summit, OECD development assistance placed greater emphasis on supporting African infrastructure. Official Development Assistance (ODA) flows almost doubled from $4.1 billion in 2004 to $8.1 billion in 2007. Private investment flows to Sub-Saharan Africa infrastructure almost tripled, going

from about $3 billion in 1997 to $9.4 billion in 2006/07. (Figure 7 in the Annex 1) In addition, non-OECD countries, notably China and India, began to take a growing role –their commitments rose from low levels to finance about $2.6 billion of African infrastructure annually between 2001 and 2006. (Foster and Briceno-Garmendia, 2010)

3.4.1 The OECD-DAC members have a long history of engaging in Africa’s infrastructure. In the recent years, DAC members have moved towards greater coordination behind the principles of the “Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness” and “Accra Agenda for Action” to strengthen country public management and accountability

systems. There are three channels through which infrastructure could affect growth and poverty reduction: a) promote economic activity and growth, and reducing transaction cost; b) alleviate the growth bottlenecks which prevent the poor to participate in the market; and c) allowing the poor to benefit from economic growth by creating job opportunities and reducing risks. Four principles can be derived: a) use country-led framework for coordination; b) enhance the infrastructures impact on the poor; c) improve management to achieve sustainability; and d) increase

infrastructure financing and use them efficiently. (Shoji, POVNET)

3.4.2 Over the years, the traditional approach of “project support” has given way to“sector-wide approach” where government and development partners are jointly involved in implementing the sector strategy, policy and

development program. Infrastructure delivery requires policy dialogue and donor coordination, transparency and accountability, as well as good governance and sustainability. Major initiatives include EU-Africa Partnership on Infrastructure, Infrastructural Consortium for Africa (ICA), Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostics and North-South Corridors, and West Africa Power Pools. In particular, Infrastructure Consortium for Africa is encouraging, supporting and promoting increased investment in infrastructure in Africa, aimed to enhance and accelerate the development of Africa’s infrastructure. (Kettner,EU)

3.4.3 EU-Africa Partnership on Infrastructure established in 2007 is a partnership working in three levels, continental, regional and country and plays a key role in planning and implementing the joint EU-Africa Strategy. It finances infrastructure and support regulatory framework that facilitates trade and services. Interestingly, the Infrastructure Trust Fund is an innovative example of cooperation among European development institutions including bilateral agencies, the EC, member states and the European Investment Bank (EIB) to promote financing for regional infrastructure projects in Africa. Launched in 2006, The Fund subsidises the financing of infrastructure projects, through a ‘blending mechanism’, mixing grants from donors with long-term investment finance from

financiers. According to the 2009 Annual Report: ‘this blending acts as a catalyst for investment, mitigating the risks taken by the promoters and financiers and providing an incentive to consider investment in projects with substantial development impact but low financial return that could not otherwise be envisaged’. Eligible projects must be based on African priorities and be trans-border projects or national projects with a regional impact on two or more countries.7 (Kettner, EU)

3.4.4 Africa Infrastructure Program (USAID) is a three-year program, which began in September 2008, to provide capacity building and late-stage transactional support services on clean and conventional energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa. AIP is funded principally under the African Global Competitiveness Initiative, operated in conjunction with USAID African regional and bilateral missions, providing support to host country governments,

regional economic communities and private project developers. It recently completed activities in Nigeria and Kenya and is currently providing services to several renewable and conventional energy projects in Ghana, Nigeria, Mozambique, Namibia, Kenya and South Africa.8

3.4.5 Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) is a joint initiative of the African Union Commission (AUC), the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) Secretariat, and the African Development Bank (AfDB) Group. Launched in July 2010, ‘PIDA’s objective is to merge all continental infrastructure initiatives into a single coherent programme for the entire continent’. To do this, it will merge the NEPAD Short-Term Action Plan, the NEPAD Medium-to-Long Term Strategic Framework and the African Union

Infrastructure Master Plan Initiative, thus providing an important framework for the delivery of trans-boundary infrastructure, and establishing a clear ‘roadmap’ for Africa’s infrastructure development. Its activities will

focus on the development of transportation, energy, information and communication technologies, as well as trans-boundary water basins.9

3.4.6 The Sub-Saharan Africa Transport Policy Program (SSATP) is an international partnership of 35 SSA countries, all SSA Regional Economic Communities, more than 12 multilateral and bilateral institutions and

NGOs whose purpose is to promote the formulation and implementation of sound transport policies, leading to safe, reliable, and cost-effective transport, freeing people to lift themselves out of poverty, and helping countries to compete internationally. Currently, SSATP is preparing for a mid-term review of its Second Development Plan, and is considering increasing synergies with initiatives such as ICA and PIDA. (Koumare, SSATP)

4. Going Forward: Opportunities and Challenges

4.1 The G-20 Summit held in Seoul, Korea, highlighted that the global economy is now supported by multiple growth poles. “Developing countries in Africa could become growth poles if infrastructure and other constraints can be removed” (Lin 2010). Developing countries’ share of global export and FDI has also grown quickly. In terms of exports, developing countries’ share in global exports rose from 22 percent in 1980 to 31 percent in 2008. In terms of FDI, developing countries’ share in global FDI was 7 percent in 1980, rising to 32 percent in 2008 (with 21 percent coming from the developing-country members of the G-20(Fardoust 2010)).

4.2 Investing in bottleneck-releasing infrastructure projects in developing countries is an important way of creating demand for capital goods, which will contribute to the global recovery as well as to a sustainable and inclusive global growth. External assistance could be channeled to economically profitable investments in African countries. Discussions at this China- DAC Study Group event about infrastructure showed that although China and DAC members represent two different, but equally long, traditions of providing aid to foreign countries, they face similar challenges (e.g. in terms of country ownership and sustainability and poverty impact) and can learn from how each is responding.

4.3 DAC members have moved towards greater co-ordination behind the principles of the “Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness” to strengthen country public management and accountability systems. China, to increase sustainability, is basing its cooperation around an enterprise-based approach, using both concessional and nonconcessional financing, with significant and sustained involvement in management by Chinese state and private sector enterprises.

4.4 There are opportunities to bring these two approaches together in a way that can improve the collective impact of infrastructure development in Africa on growth and poverty reduction. In particular, the European Infrastructure Trust Fund in particular has been using a ‘blending mechanism’, mixing grants from donors with

long-term investment finance from financiers.

4.5 As the experience of China suggests, political leadership and strategic policy and planning capacity combined with pragmatic step by step adjustment to evolving needs and opportunities are important factors in

building infrastructure. "Soft infrastructure", in terms of the capacity to ensure efficiency and poverty impact in project selection and implementation/operation/maintenance is a key part of this. (Carey, OECD-DAC)

4.6 Infrastructure is complex and different principles apply. Infrastructure covers multiple sectors ranging from those in the categories of the public goods and semipublic goods, and the private goods (such as the extractive industries). Thus different types of infrastructure need to be financed by very different ways, sometimes by government budget and ODA, other times by a combination of both public and private (concessional and non-concessional) financing sources. This is as shown by the conceptual framework in Section 1. There are clearly different rules for international donors, those for private sector investors engaging in PPI projects, and those which

are purely commercial deals.

4.7 More inclusiveness for diversified approaches seems to be needed in infrastructure financing. “An ambitious and comprehensive approach is needed to tackle the interlocking problems impending Africa’s growth and development. This must involve the diversification of products and markets, development of skills and human

resources, modernization of technology and infrastructure, re-engineering of business processes, creation of incentives for small and medium enterprises to grow and export improvement of country investment climate, and cultivation foreign direct investment. Enhancing the investment climate entails government involvement within a wide

area of governance—providing security, collecting taxes, instituting sound economic policies into law, and delivering adequate public services.”(Cheru 2010, speech at the Opening Ceremony)

Box 4. For Investors in the Extractive Industries: Five Principles

4.9 African officials noted that the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) led by the AfDB is a major way forward and all international partners, including China, should support it. Participants of the GDLN consultation also noted that governments are increasingly focused on cross-border regional infrastructure and are also encouraging greater private sector participation in regional infrastructure development. Participants felt that projects such as the Tanzania Zambia Railway (TaZaRa) which were developed in conjunction with the Chinese should be replicated given its transborder nature and its significant impact on the development of those countries involved(ACET 2010).

4.10 Concrete actions for China as a development partner. African officials have identified specific actions China can take in supporting the development of regional infrastructure in Africa, in particular, addressing issues related to transparency,international competitive bidding, creation oflocal jobs, and sustainable development. More specifically, These include: a) Provision of concessionary financing targeted to specific sectors; b) Provision of

credit enhancement mechanisms (e.g. guarantees) to decrease perceived risk and jump start specific projects that encourage cross border integration. c) Provision of project preparation facilities to assist small countries to participate. d) Focus on strengthening managerial and financial capacity in both public and private sectors; e)

Engage as a co-financing partner with financial institutions involved in African infrastructure development (such as the AfDB, Development Bank of Southern Africa, World Bank, , EU and others). “Participants agreed that if China could take on a greater role in African infrastructure development through the above mentioned actions, both China and African countries would stand to benefit significantly from both economic growth and in welfare gains for millions of impoverished people.” (ACET 2010)

4.11 Remaining Challenges to All. Developing countries, China, Africa and international development partners face a host of challenges going forward. First, strengthening state capacity in Africa is the key for the continent’s economic and political renewal. “Of course, the concern with institutions is justified, but perhaps institutional innovation used in China in the earlier stage of development can offer useful lessons” (Cheru 2010). Second, as the public sector faces severe budget constraints, public-private partnerships offer a promising solution to the financing needs. However, there are considerable risks associated with inefficient procurement policies and inadequate contracting arrangements. Sound legal frameworks are vital, especially if countries wish to attract foreign investment. (Henckel, and McKibbin. 2010)

4.12 Measurement and Evaluation. To improve efficiency and sustainability, a variety of issues in developed and developing economies need to be addressed, including: a clear definition of infrastructure in the IMF’s Government Finance Statistics (GFS), improved measurement of the returns to infrastructure; improved methods

for project evaluation; the delivery mechanisms, and the ongoing regulatory environment. Rigorous measurement and analysis around all aspects of infrastructure spending is needed to improve the disappointing performance to date. Furthermore, learning needs to be based on good evaluation. International partners need to provide better financial and technical support for evaluating projects as well as for assessing their impacts. Finally, many developing countries would benefit from greater cross-country fertilization of experiences through South-South learning, peer-reviewing, training and capacity development, especially on infrastructure development, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and EITI related issues.

Annex 1

Table 1. Africa’s Infrastructure Investment Needs and Funding Gaps

This table below shows Africa’s investment needs and funding gap in infrastructure. Indeed, Africa’sinfrastructure investment needs relative to GDP are particularly large, at 15 percent of GDP. After considering

efficiency gains from improvements in soft infrastructure (such as improvements in governance, regulation and

cost recovery, the region’s annual funding gap would remain sizable at about 5 percent of GDP, or about $31

billion.

Source: World Bank, Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic, 2009.

Figure 1. China: Before- and After-Tax Return to Capital, Excluding Residential Housing and Including Inventories, 1978-2005

Source: Bai, Hsieh and Qian 2006. Figure 9.

Figure 2. Investment in Fixed Assets in Transportation Sector(1953-2010): Amount and Growth Rate

Source: Guo Xiaobei, 2010.

Figure 3. China’s Road Transportation

Source: Guo Xiaobei (2009).

Figure 4: Growth of township roads in China 1995–2002 (km)

Source: Dong and Fan (2004).

Table 2. Sources of financing for highway construction from 1950 to 1980 (%)

Source: Guo Xiaobei, 2010. Paper prepared for the China-Africa High Level Experience Sharing Program

organized by the Government of China and the World Bank.

Table 3. Investment structure of highway construction in China (2000-2007)

Source: Guo Xiaobei, 2010. Paper prepared for the China-Africa High Level Experience Sharing Program organized by the Government of China and the World Bank.

Figure 5. China’s FDI outflow to Africa, 1999-2009 in millions of dollars

Source: CEIC and MOFCOM, and http://www.gov.cn

Figure 6. Composition of China’s outward direct investment in Africa by sector (by the end of 2009)

Source: State Council. The Government of China, White Paper on China-Africa Economic and Trade Cooperation, December 2010. Part II, page 4.

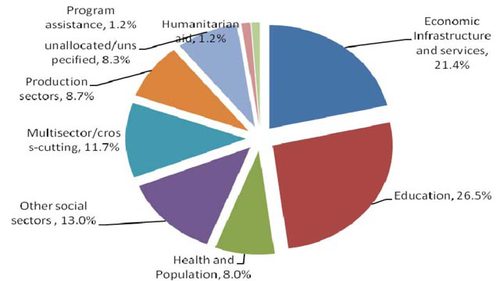

Figure 7 Infrastructure as a percentage of Official Development Aid for Sub-Saharan Africa 2002-2008

Source: Yan Wang’s calculation based on a broad definition including all ODA in social and economic

infrastructure by both bilateral and multilateral organizations as a perceptage of total ODA, extracted from the OECD-DAC database. The time series shows a slight upward trend except for 2006 due to debt relief efforts.

References

Background papers for the Infrastructure event

Chen, Chuan, “Chinese Participation in Infrastructure Development in Africa: Roles and Impacts”, a background paper commissioned by the European Commission, for the China-DAC Study Group’s third event

on “Infrastructure: The Foundation for Growth and Poverty Reduction,” Sept 19-20, 2010, Beijing China.

Wang, Haimin, “China’s Experience in Infrastructure Development: From the Perspective of Growth and Poverty Reduction”. Background paper commissioned by the European Commission, for the China-DAC Study Group’s third event on “Infrastructure: The Foundation for Growth and Poverty Reduction,” Sept 19-20, 2010, Beijing China.

Petersen, Hans E., and Sanne van der Lugt, “Chinese Participation in African Infrastructure Development: The

case of the DRC and Zambia”, a background paper commissioned by the European Commission, for the China-DAC Study Group’s third event on “Infrastructure: The Foundation for Growth and Poverty Reduction,”Sept 19-20, 2010, Beijing China.

ACET (African Centre for Economic Transformation) 2010b. Summary of the GDLN Consultation on Infrastructure, held on September 7, 2010.

Other References:

Adenikinju, Adeola, 2005, Analysis of the cost of infrastructure failures in a developing economy: The case of

the electricity sector in Nigeria, AERC Research Paper No. RP_148

Bai, Chong-En, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Yingyi Qian 2006. “The Return to Capital in China”, NBER Working

Paper No. 12755, December 2006.

Brautigam, D. 2010. “Chinese Finance of Overseas Infrastructure” Paper prepared for and presented at the

China-DAC Study Group’s third event on Infrastructure.

Dong, Yan, Hua Fan, 2004, Infrastructure, Growth, and Poverty Reduction in China, Shanghai Global Poverty Conference Case Study, World Bank Working Paper 30774;

Estache, Antonio, 2006, Africa’s Infrastructure: Challenges and Realizing the Potential for Profitable

Investment in Africa. IMF and Joint Africa Institute. Tunis, Tunisia.

Fan, Shenggen and Connie Chan-Kang, 2005, Road Development, Economic Growth, and Poverty Reduction

in China, IFPRI Research Report 138.

Fay, Marianne, Michael Toman, Daniel Benitez and Stefan Csordas, 2010. “Infrastructure and Sustainable

Development” chapter 8 in Fardoust, Kim and Spepulveda, eds. Post-crisis Growth and Development, the World Bank.

Fay, Marianne and Michael Toman. 2010. “Infrastructure and Sustainable Development” a paper presented in Korea-World Bank High Level Conference on Post-Crisis Growth and Development, June 3-4 2010, Busan, Korea.

Foster, Vivien, William Butterfield, Chuan Chen and Nataliya Pushak. 2008. Building Bridges: China’s

Growing Roles as Infrastructure Financier for Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank and PPIAF. Foster, Vivien and Cecilia Briceno-Garmendia. 2010. “Africa’s Infrastructure: A time for transformation”. A copublication of the Agency Francaise de Development and the World Bank.

Guo, Xiaobei, 2009, Development Experiences of China’s Transport Infrastructure, Working paper commissioned by WBI, for China-Africa Experience Sharing Program co-organized by the Government of China and the World Bank.

Henckel, Timo, and Warwick McKibbin. 2010. “The Economics of Infrastructure in a Globalized World: Issues,

Lessons and Future Challenges.” Conference summary. June 4, 2010.

Krishnaswamy, Venkataraman and Gary Stuggins, 2007, Closing the Electricity Supply-Demand Gap, World

Bank Energy and Mining Sector Board Discussion Paper, Paper no. 20.

Li, Zhigang. 2010a. “Some evidence on the performance of transport infrastructure investment in China,”

presentation given at the conference “The Economics of Infrastructure in a Globalised World: Issues, Lessons and Future Challenges,” Sydney, 18-19 March, available at http://cama.anu.edu.au/Infrastructure_Conference.asp.

Li, Zhigang, 2010b. Estimating the Social Return to Transport Infrastructure: A Price-Difference Approach

Applied to a Quasi-Experiment.” Working Paper presented at the China-DAC Study Group’s 3rd event.

Li, Han and Li Zhigang, 2010. “Road Investment and Inventory Reduction: Firm Level Evidence from China.”

Working paper presented at the China-DAC study group’s 3rd event.

Lin, Justin Yifu. 2010. “A Global Economy with Multiple Growth Poles” chapter 3 in Fardoust, Kim and

Spepulveda, eds. Post-crisis Growth and Development, the World Bank.

Lin, Shuanglin, 2001, Public Infrastructure Development in China, Comparative Economic Studies, Summer

2001, v. 43, iss. 2, pp. 83-109

Liu, Zhi, 2005, Planning and Policy Coordination in China’s Infrastructure Development --A Background Paper

for the EAP Infrastructure Flagship Study

Lu, Y. J. and Wang, S. Q. (2004). Project Management in China. Southeast Asia Construction, Issue Sept/Oct

2004, pp. 158-163

Mbekeani, Kennedy K., 2007, The Role of Infrastructure in Determining Export Competitiveness: Framework

Paper, Supply Response Working Paper No. ESWP_05

Ministry of Finance and World Bank 2010. Sharing Knowledge on Development, Promoting Harmony and

Progress: 30th Anniversary of the China and World Bank Cooperation.

NDRC (National Development and Reform Commission, Department of Foreign Capital and Overseas

Investment). 2009. 1979-2005 China’s Experience with the Utilization of Foreign Funds. Beijing:China Planning Press (in Chinese.).

Ndulu, Benno J., 2006, Infrastructure, Regional Integration and Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Dealing with

the Disadvantages of Geography and Sovereign Fragmentation, Journal of African Economies, Vol.

15, Issue 2, pp. 212-244, 2006

OECD-DAC. 2006 “Promoting Pro-poor Growth: Infrastructure”. POVNET.

Peterson, George E. 2008a. Unlocking Land Values to Finance Urban Infrastructure. Trends and Policy

Options Series. Washington, DC: PPIAF.

Peterson, George E. 2008b. “Unlocking land values to finance urban infrastructure: Land- based financing

options for cities”. GRIDLINES, PPIAF and World Bank.

http://www.ppiaf.org/ppiaf/sites/ppiaf.org/files/publication/Gridlines-40-

Unlocking%20Land%20Values%20-%20GPeterson.pdf

State Council, the government of China. “China-Africa Economic and Trade Cooperation” a White Paper,

December 2010. Accessed at http://www.gov.cn/english/official/2010-12/23/content_1771603.htm