2011.06-Working Paper

Acknowledgements

The author would especially like to thank Mr. Peniel Lyimo, Permanent Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Office of Tanzania for his support for the team to prepare this study, and Dr. John McIntire, the World Bank’s Country Director of Tanzania, Uganda and Burundi, Dr. Paolo Zacchia, Lead Economist of the World Bank Country Office in Dar es Salaam, for supervising the study. The author also appreciates very much for the continuous help and support

given by Mr. Adam, Nelson, the Country officer of the World Bank Country Office in Dar es Salaam. The author acknowledges the support from Dr. Wu Zhong, Ms. He Xiaojun and Ms. Li Shaojun of the International Poverty Reduction Center in China (IPRCC).

Dr. Madhur Gautam, Lead Economist and Dr. Zainab Zitta Semgalawe, Senior Rural Development Specialist of the World Bank Country Office in Dar es Salaam provided advice and helped engage with the Ministry of Agriculture Food Security and Cooperative of Tanzania.

The author would like to thank Mr. Lucas K. Ayo and Ms. Rehema J. Ngalla from the Ministry of Agriculture Food Security and Cooperatives of Tanzania for their field study assistance.

Finally, the author would like to acknowledge those whose studies are cited and used by this report, and financial support provided by the DFID Trust Fund.

Executive Summary

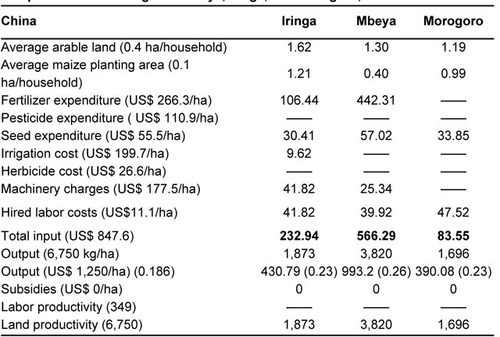

1. This document reports on an agricultural development and poverty reduction exchange program between Tanzania and China, jointly facilitated by the World Bank’s Tanzania office and the International Poverty Reduction Center in China (IPRCC).2 It is primarily based on existing studies, rapid field visits to three regions (Morogoro, Iringa, and Mbeya), and interviews with World Bank staff in Dar es Salaam, government officials, and development partners.

2. The report is not intended to discuss current strategies, policies, and programs implemented by the Tanzanian government, analyze Tanzania’s agricultural development, nor introduce Chinese agricultural development. Instead, some key issues identified from among the many studies conducted in Tanzania are discussed with the reference to how China has coped with similar issues and situations. This report will serve as

reference material for the action learning team that includes Tanzanian senior officials, researchers, and representatives of farmer organizations.

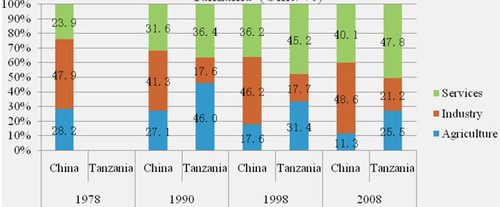

Agriculture Drives Economic Growth andPoverty Reduction in China

3. China’s agricultural growth has been the major pillar of economic growth and poverty reduction over the last three decades. Massive reduction of rural poverty is the result of increased agricultural productivity during the 1980s, followed by continuous migration to the cities. The rural population decreased from 80 percent in the 1980s to about 55 percent in 2000. This population shift was concurrent with a rapid increase in agricultural labor productivity and capital flowing from agriculture to other sectors, particularly laborintensive manufacturing and service sectors that

absorbed the rural labor force. China’s pro-poor agriculture-based growth has created a development path that successfully coupled agricultural development and poverty reduction.

4. Tanzania is endowed with a diverse climate, plentiful land and water resources with regional variations, and a strategic location on the East African coast that borders eight countries and provides easy access to both regional and global markets. These factors provide a comparative advantage for the agricultural sector, but low productivity, a decline in agricultural exports, rapid population growth, and an underdeveloped rural non-farm sector have constrained agricultural growth. It has not contributed to the Government’s poverty reduction goals.

5. In spite of vast differences, in the early 1980s China and Tanzania were both primarily rural societies, with agriculture playing a similar role in their economies. Agriculture has been a substantial contributor to overall economic growth in both countries, even though China had less favorable land tenure, rural financing, and agricultural taxation than Tanzania. The two counties started pro-market reforms at more or less the same time, which raises these questions — why have two countries that both embarked on market reforms reached such different development stages, and, is it possible for Tanzania to learn from China’s success in agricultural

development and poverty reduction?

6. China’s development process follows an incremental learning process during which “policy experiments” occur in areas with a problem. Experience and lessons learned are used to create

formal policy with extended piloting in different areas, usually in all provinces. After the policy has proved successful in pilot areas, application on a larger scale is implemented. Training and capacity building are conducted along with the experiments, an approach that has brought significant success to most of China’s policies and strategies.

7. The Tanzanian Government developed and implemented many agricultural strategies and policies during the last 10 years, but these “experiments” have largely focused on technical issues and have rarely been institutionalized because there is a lack of structure and capacity. Large-scale country-wide application without careful experimentation can often create serious barriers to successful implementation. Developing an experimental policy process on a small scale is essential so that new ideas can be scaled up in a controlled manner for implementation.

Vital Role for Agriculture in Both Countries

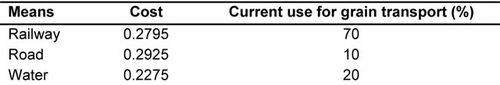

8. Agriculture plays a vital role in the social and economic life of both China and Tanzania — more than 60 percent of the Chinese population and 80 percent of the Tanzanian population live in rural areas. In China, agriculture began to grow rapidly in the late 1970s due to economic policy changes such as land reforms and increased prices. From 1978 to 1984, China experienced average annual agricultural growth of 8.0 percent, and has averaged 4.3 percent over 30 years. Tanzania has maintained an economic growth rate of more than 6 percent since 2000, but poverty declined by only 2 percent over those years. The overall growth rate has not been accompanied by the necessary growth rate of agriculture and crop production. However, at an average annual growth rate of 4.4 percent over the last 10 years, Tanzania’s agricultural growth exceeds the Sub-Saharan African average of 3.3 percent.

9. During the 1970s, China’s per capita agricultural GDP was less than US$ 100 (constant 2000 prices), while the figure for Tanzania was more than US$ 160 during the same time period. China’s per capita agricultural GDP then doubled to about US$ 200 in the 1980s, while in Tanzania the figure dropped to US$ 130. Tanzania’s per capita agricultural GDP began to increase after the year 2000, albeit at a slow pace (1.4 percent annually from around US$ 140 in 2000 to US$ 160 in 2007). During same period, China’s per capita agricultural GDP increased by 3.3 percent from US$ 200 to US$ 270.

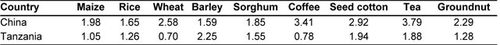

10. Increases in yields of major crops in China are associated with improved productivity. From 1978 to 2008, maize yields increased from 2.8 metric tonnes per hectare to 5.6 metric tonnes. In Tanzania, maize production declined or stagnated over recent years. Other crops in China — such as rice and wheat — followed a growth pattern similar to maize. Except for tea, the productivity of crops in Tanzania has not significantly improved over the

same period. China’s crop production increased mainly because land productivity improved, even though arable land decreased due to rapid urbanization. In Tanzania, crop production improved largely through area expansion rather than increased productivity, which may explain why agricultural growth has not led to significant poverty

reduction.

11. Agriculture is a vital sector in both China and Tanzania. In the 1970s, the agriculture share of Tanzanian GDP was 49 percent, but declined to 46 percent in 2002 and 25 percent in 2008. In China, the agriculture share of GDP was 28 percent in the 1970s, declining to 11 percent in 2008. Although the agriculture share of GDP has declined in both countries, agriculture is vital for economic growth, particularly during the early stages of China’s economic expansion.

12. Tanzanian GDP grew by 4.8 percent in 1999, while agriculture grew by 1.3 percent, or 27 percent of GDP. In 2001, GDP grew by 6.0 percent and agriculture grew by 1.5 percent, or 25 percent of GDP. Agriculture’s contribution to economic growth was 14 percent of GDP in 2003, 21 percent in 2004, and 16 percent in 2008. The contribution from agriculture to overall economic growth has never been more than 25 percent. The low growth rate of agriculture, along with the sector’s employment of a majority of the Tanzanian population, partially explains why economic growth has not substantially reduced poverty.

Lessons from the Chinese Strategy

13. Agriculture’s backward and forward links and pro-poor growth pattern have enabled China’s remarkable poverty reduction. In Tanzania, the economic structure and growth pattern restricts the poor from fully benefiting from economic growth. The Chinese strategy offers several lessons. First, economic growth should bring significant structural transformation for efficient poverty reduction. Second, economic sectors must be inter-connected to avoid “isolated growth islands.” Third, for rapidly growing sectors to affect poverty, they should have links to those sectors that already employ a large share of the labor force or links to those that can attract labor on a large scale. Generating a growth chain rather than a growth island is essential for linking growth and poverty reduction.

14. To build growth chains it is necessary to promote a targeted growth pattern — a consistent relationship between growth and poverty only happens under certain conditions. When a large population is engaged in agriculture, high agricultural growth rates that produce a surplus are necessary so that the surplus that exceeds

consumption can be traded through either domestic or international markets. (China fits the former case, while Tanzania could exploit both markets given its high potential in agriculture and relatively low domestic market demand.) Lower food prices from increased agricultural production can reduce costs to make industrial and services sectors more competitive. Capital from agricultural surplus can create opportunities in manufacturing or other sectors that can absorb labor from the agriculture sector. Like China in the early 1980s and Tanzania today, there is insufficient domestic capital for the economy to grow, and thus requires foreign investment to significantly accelerate this process.

15. The dominant role of maize in Tanzanian agriculture and broader society suggests that a maize-led agricultural development strategy for domestic food security, value chain development, and exports have the potential to change Tanzanian agriculture from subsistence to commercial. Tanzania, like China, has a dual agricultural structure, with both subsistence smallholders and large-scale cash crop farmers. Exports are important to foster smallholder agriculture and increase farmer income, but reliance on only cash crops is not enough to support

agricultural growth and poverty reduction.

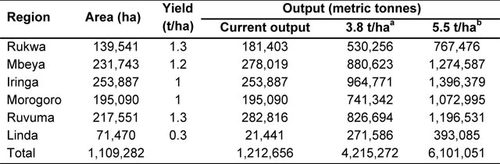

16. Further increasing food crop production requires greater demand, which can be stimulated through a value-added development chain and exports. Tanzania needs a broader view of its agricultural export strategy. Increasing international food prices driven by a rapid increase in food demand provides Tanzania with an opportunity to develop a broad-based export agriculture. Starchbased crops such as maize, cassava, and sugarcane are the most promising exports. Maize in particular can create long value chains from feed production to biofuel. Such an agricultural value chain would provide Tanzania with a powerful engine for transforming its substance agriculture to commercial agriculture, and potentially lead to poverty reduction along with increased agricultural competitiveness.

17. Tanzania has great potential for developing commodity crop production clusters. With easy access to existing railway networks, trunk roads, and ports in Dar es Salaam, Mtwara, and Tanga, and the country’s borders with eight neighboring countries, there are certainly opportunities to increase food exports. In particular, the area along the TAZARA railway line and TANZAM highway from Dar es Salaam to Rukwa could be developed into “Tanzania Food Basket Corridor” with relative ease. With abundant maize and bean production along the Food

Basket Corridor, in addition to other crops, the area could also produce livestock feed using crop residue.

18. Developing a Food Basket Corridor requires a strategic approach. Experience from China suggests careful experimentation before proceeding to large-scale investments. Policy experiments could include projects such as land surveys and distribution of labor, seed and fertilizer distribution, storage facilities and pricing, transportation,

scalability of farmland, farm mechanization, and capacity building. Morogoro would be an ideal place for policy experiments.

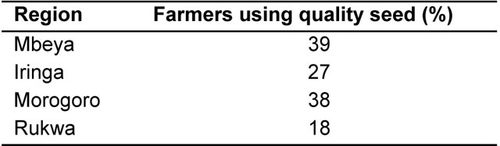

19. Different levels of agricultural productivity in China and Tanzania are the result of different inputs and levels of inputs. Chinese farmers, including smallholders, use higher levels of inputs, particularly improved seed and fertilizer, which are relatively inexpensive, and have access to research and extension centers. In Tanzania, most farmers do not use improved seed and fertilizer due to relatively high costs. Conditions are difficult, with limited

irrigation and mechanization as well as relatively weak research and extension services. For Tanzania to improve its agricultural productivity, strategies and policies should focus on measures to improve total factor productivity, particularly improved seeds and fertilizers.

Tanzanian Growth Not Based on Agriculture

20. Tanzania’s solid economic growth has to a large extent been built on non-agricultural sectors. Failing to adjust this growth pattern would continue to elevate poverty levels. The 3.6 percent budget allocation to agriculture in FY 2008/09 is inadequate relative to the sector’s importance for poverty reduction. The multiple and mixed priorities for education, health, and agriculture, for example, do not help any sector to develop within the limited financial means of the Government. Given the high social, economic, and political profile of maize in Tanzania, it could be considered as a national crop to be prioritized at the center of the public investment strategy.

21. China’s agricultural learning process suggests that market mechanisms only work when both marketplace and infrastructure (roads and storage) are in place. To provide adequate infrastructure requires full awareness of the importance of the state in public investment. Road development has been the largest investment sector by the Government of Tanzania over the last 30 years. However, transport still makes up a large portion of market costs. To ensure better awareness of public investment for agricultural growth, it would be beneficial to place Tanzania’s agricultural policy group under the Prime Minister’s Office, which is able to provide adequate political support and oversight.

22. At the same time, the role of the ruling party should be considered. A high-level working group for policy learning could be developed within the ruling party so that it can consistently advise the Government about policy development. Tanzania’s Government might want to consider approaching China for experience and lessons learned in this area. It is important that strategy and policies are based on the country’s specific conditions, which

requires a stable institutional structure as well as a Government think tank to focus on agricultural policy development. This is a long-term task and needs a consistent policy and strategy process. Increasing food crop production requires creating a larger demand by developing a chain of added value and exports, which demands a broad export strategy.

23. Tanzania has taken very serious measures to promote growth and poverty reduction over the last decade, and overall economic growth has been encouraging. Agriculture is the center of the Government strategy to tackle poverty. The country has developed a series of policies to promote agriculture as the engine of growth and poverty

reduction. Agricultural growth under those measures has been positive, however, this reasonably high growth in the overall economy and agriculture has not led to significant poverty reduction. The challenge is to accelerate agricultural development and thus reduce poverty.

Introduction

24. China’s remarkable economic growth and rapid poverty reduction over the last three decades are attracting global interest, particularly from most African countries and the international development community. From 1978 to 2008, the annual average economic growth rate was about 9 percent. The incidence of poverty dropped from 84 percent in 1981 to 5.4 percent in 2007, measured by US$ 1.25 PPP (Ravallion, 2007). Although China’s growth is

largely broad-based, agriculture has been a significant factor. The agricultural sector still maintains the highest poverty-growth elasticity accounting for 1.51 percent, while the industry and service sectors account for 1.09 percent and 0.73 percent respectively, even after entering the new century (Li Xiaoyun, 2010b).

25. The average annual agricultural growth rate since the end of the 1970s was about 4.4 percent; the average annual population growth rate was 1.07 percent, while farmer income increased at about 7.1 percent annually. Agriculture has been the major pillar for the country’s growth and poverty reduction. Massive rural poverty reduction increased land productivity in the 1980s, followed by a continuous decrease of the rural share of the population, from more than 80 percent in 1980s to about 55 percent in 2000. Agricultural labor productivity increased and capital flowed out of agriculture to other sectors as labor-intensive manufacturing and services developed to absorb the rural labor force. Incentive-based pro-market reforms catalyzed the process in which economic growth and social transformation took place.

26. Agricultural changes within this development path have gone through the three stages:

27. Agricultural output increased, mainly in cereal production that reduced food insecurity from the beginning to the middle of the 1980s, largely due to land reforms that turned collective farms to an individual land leasing system. During this stage, the state substantially raised the official purchase price for cereals and began to relax market controls. Total cereal production soared from 316 million metric tonnes in 1977 to 407.3 million metric tonnes in 1984. Average cereal grain processing rose from 290 kilograms to 390 kilograms per capita during the same time period.

28. Agricultural output grew continuously, accompanied by an increase in production diversification after the middle of the 1980s as agricultural markets became more liberal, for example, state controls on the cereal market and regional trade barriers were removed. During this stage, the agricultural structure began to diversify, from one dominated by cereal crops to a diversified structure based on food crop-cash crop-livestock. Importantly, a labor-intensive manufacturing sector began to emerge that could accept the surplus labor that had no place in farming. Farmers’ income increased largely because labor productivity in agriculture also increased (the number of rural

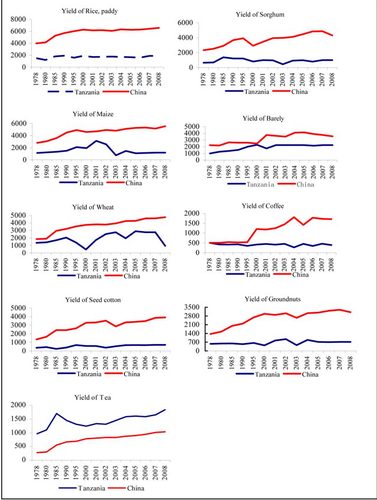

laborers began to decrease). Income diversified away from agriculture and non-agricultural employment rose. These two stages have seen the most rapid poverty reduction in Chinese history. The poverty incidence reduced from 30.7 percent in 1978 to 9.4 percent in 1990, with subsequent reductions to 9.4 percent in 1990 and 2.5 percent in 2005. Most poverty-stricken people were lifted substantially out of poverty during the 1980s.

29. Rapid poverty reduction, urbanization, and industrialization after the end of the 1990s continuously drove rural labor toward the urban, industrial, and service sectors, and promoted further labor productivity as the number of rural laborers decreased and land productivity rose as arable land transferred to the urban and industry sectors. This

took place under increasing investments in agriculture, increasing many subsidies through the so called “urban and industry support rural and agriculture” policy.

30. Tanzania, like other African countries, is still a typical agrarian society with poor people topping 80 percent. Agriculture is central to the economy and employs about 85 percent of the population. Primary agriculture has been a

substantial contributor to overall national growth, accounting for more than 37 percent of the GDP from 1995 to 2003 with a GDP growth rate of about 5.8 percent in 2003 (Gordon, 2008). Tanzania has a very favorable climate for agriculture with abundant land and water with regional variations, and a strategic location on the sea and shared borders with eight countries, which could easily benefit agriculture with access to both regional and global markets. Tanzania has favorable conditions for agricultural production with comparative advantages.

31. The Tanzanian Government recognizes the potential of its agricultural development and the role of the agricultural sector in economic growth and poverty reduction. Compared to a growth rate of 2.9 percent in the 1970s and 2.1 percent in the 1980s, Tanzania’s agricultural growth reached an annual average of 3.6 percent in 1990s, and continued at 3.9 percent up to 2007, exceeding the Sub-Saharan African average of 3.3 percent (Gordon, 2008).

From 1996 to 2003, the average agricultural growth rate was 4 percent. From 1998 to 2008, agricultural GDP grew at 4.4 percent annually. Food self sufficiently averages 102.5 percent, which makes Tanzania the highest internal producer in Africa (MAFSC, 2008). Food shocks due to weather variability have been avoided (Gordon, 2008), and

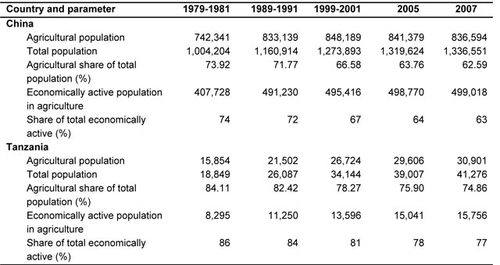

cereal and horticulture producers participate in regional and global markets to a much greater extent than in the past. These encouraging performances in Tanzania’s agricultural sector can be attributed to structure and policy changes that the Government enacted to accelerate its agricultural sector, all of which suggest positive steps toward poverty reduction.

32. The Government of Tanzania has taken serious measures to develop its agriculture during the post-structural adjustment era. The Agricultural Sector Development Strategy (ASDS) of 2001 marked the initial shift of the Government’s development strategy to favor the agricultural sector and domestic food security. The measures included in the ASDS provided opportunities for farmers to improve their production. The Agricultural Sector Development Program (ASDP) of 2005 included the overall strategy of Mkukuta, the Tanzanian poverty reduction strategy and other related strategies such as the public sector reform program and the decentralization program. The ASDP was implemented by developing the Village Agricultural Development Plan, which is incorporated into the

District Agricultural Development Plan.

33. The ASDP was implemented in a more organized way than any other previous activities. It has a clear responsibility framework from the Prime Minister’s Office to the regional administration and local governments as well as the four Agricultural Sector Lead Ministries. Along with implementation of the programs, the Government has also introduced a farm input subsidy program, irrigation strategy, mechanization strategy, improved seed production

and dissemination program, and warehouse receipt system. Kilimo Kwanza (Agriculture First) is the new plan to strengthen major components of the ASDP and strengthen leadership in terms of Government intervention such as establishing the Agricultural Development Bank and the added value of the private sector. The Government budget

implementing these programs increased significantly from 4.6 percent in 2007/08 to 6.1 percent in 2008/09 (MAFSC, 2008). The institutional and financial framework developed over the years shows significant progress in the Government’s commitment to agriculture and its capacity to implement an agricultural development strategy.

34. With a rapid population growth rate of 3.3 percent during 1980 to 1990, and 2.2 percent from 1990 to the 2000s, agricultural growth was 3.6 percent and the net growth rate was only 1.5 percent. Even with a reasonable growth rate, a robust per capita growth rate in the agricultural sector has not been achieved (URT, 2006). Population growth along with the poor technology used by Tanzanians has adversely affected the agricultural sector, the environment, and economy. Although the country’s population density is still low — at 26 people per square kilometer — settlements are spreading to agriculturally marginal lands and achievements are insufficient to make a significant difference in terms of per capita income and rural poverty (Gordon, 2008).

35. Agriculture has performed poorly in the following terms:

• Increased agricultural output increase has come mainly from area extension, for example, since the 1980s maize increased its area share, but lost output value.

• Agricultural exports grew at the rate of agricultural growth due to the modest improvement in incentives, but not

sufficiently to significantly accelerate export expansion. The traditional export crop sector has reduced its area share from 10 percent to 7.4 percent since the 1980s, and has a stagnant value share at around 5.5 percent, while the non-traditional export sector accounts for about 40 percent of all agricultural exports, but it has not been a dynamic sector (Binswanger-Mkhize and Gautam, 2009).

• Land and labor productivity are low. Tanzania needs to have at least a 2.7 percent annual increase in labor

productivity to overtake the 2.3 percent annual increase in its agricultural labor force in order to reach 5 percent annual growth in agriculture (Gordon, 2008). In the period 1990 to 2003, Tanzania’s labor productivity grew at 1.1 percent, far below the target, which is largely explained by poor incentives for productivity, bad macroeconomic policies, and poor investment decisions by parastatals, which resulted in capacity expansion when existing capacity was grossly underutilized. However, total factor productivity in 2006 was slightly higher than it was in 1961. As a consequence,

• The rural non-farm sector has grown sluggishly, and

• The decline in the national and rural poverty rates has not been encouraging. The poor performance of Tanzanian agriculture is regarded as a consequence of poor incentives, low profitability, inability of farmers to accumulate capital, and an inward-looking agricultural growth strategy (Binswanger-Mkhize and Gautam, 2009).

36. The missing links between agricultural growth and poverty reduction have been discussed within the Tanzanian government, the public, and the donor community. Over the last decade Tanzania has been following the same path to develop its agriculture as other developing nations, while China successfully coupled agricultural

development and poverty reduction. For agriculture to become the primary driving force for growth and poverty reduction, Tanzania needs to review its growth patterns, economic structure, and public and private investments in agriculture and learn from other countries, particularly the combined roles of the state, the market, and public and private investment policies.

37. Despite huge size differences in population, country, and domestic markets, in the beginning of the 1980s both China and Tanzania had primarily rural agricultural structures with a similar state role in the economy. They even had similar political systems in which the legacy of socialism provided important preconditions such as literacy, primary and basic health care and education, and most importantly, a long-lasting social and political peace.

Moreover, agriculture has been a substantial contributor to overall economic growth, accounting for 37 percent of China’s annual growth rate, even though the country had even less favorable conditions of land tenure, rural financing, and agricultural taxation than Tanzania did. It is therefore natural to ask whether Tanzania can learn

from China’s successful experience, in particular agricultural development and poverty reduction. With the challenges that face Tanzania to adjust the role of the state and enhance the role of the market — the same ones that China experienced from the 1980s to the 1990s — it also natural to ask whether Tanzania can learn from China.

38. Over the last 10 years, there has been an increase in learning activities between China and Africa promoted by African countries, international development organizations, and the Chinese government. Several questions remain:

• Is this learning process appropriate given the huge historic, socio-cultural, and political differences between China and Africa?

• What can African countries actually learn given the successful learning that has taken place elsewhere in the world, for example, with China learning from the West, Japan, and Singapore even though there are also huge differences?

• How can learning actually take place between Africa and China in a more effective manner?

• Can African countries afford and adopt learning development procedures encountered in the process?

• Can Africa also offer its experience and lessons to China?

39. Selecting Tanzania as an example for a comparative study, given its political and historic links with China, will help pinpoint the key elements in both development paths so that experience can be shared. The comparative analysis will not be systematic in an empirical fashion, but rather descriptive by using existing studies and limited field observations. The study will take a broad view, in particular the period 1978 to 1984 in China and 2001 to 2008 in Tanzania as a comparison because the two countries began to grow rapidly during those periods.

40. There has been a long debate about the poor implementation of Tanzania’s agricultural strategies and policies. First, no strategies and policies can be designed to be implemented on a large scale without serious pre-testing. Tanzania’s Government ambitiously developed and implemented different agricultural strategies and policies during the last 10 years. There were, however, problems during the implementation process. There was no pre-test and follow-up for these strategies and policies — no systematic policy learning process — and the implementation of Kilimo Kwanza is the typical case.

41. Second, there have been many“experiments” over the decades in Tanzania. These actions were largely concentrated in the technical field and were rarely institutionalized in a strategic and policy development process due to a lack of institutional structure and capacity. The experience and lessons learned from various development

strategies and policies in Tanzania’s agriculture have shown that a large-scale country-wide application of any strategy or policy without careful experimentation can often create a serious barrier to successful implementation.

42. The limits of strategies and policies that were not identified and adjusted before being applied on a large scale will immediately affect their effective implementation. In addition, deficient implementation of strategies and policies could affect public and political confidence, and perhaps undermine support. The failure of strategy and

policy implementation will also damage relationships with development partners. For strategies and policies to be efficiently implemented, it is sensible to develop an experimental policy process on a small scale as a test so that a large-scale application can then be undertaken in a more secure way.

43. China’s experience in most of its development process is an incremental learning process in which “policy experiments” first begin in areas where problems exist. Experience and lessons are then accumulated, after which formal policy with extended piloting is implemented in different areas, usually in all provinces. Only after

success with the pilots will the large-scale application be recommended. It is important to note that along with experiments, training and capacity building are also carried out. This approach has continued and brought significant success to most development projects.

44. This exchange program between China and Tanzania intends to introduce this approach as a trial for proposed solutions that will tackle Tanzania’s challenge to transform smallholder agriculture and reduce poverty. The study was proposed during the inception mission. The program aims to build an action learning process that would support the action learning team to develop the Tanzania Agricultural Development Experimentation Plan based on China’s experience through analytical studies, workshops, a study tour to China, and program development.

45. This study will not discuss the strategies, policies, and programs that the Tanzanian government is currently implementing, nor undertake a comprehensive analysis of Tanzania’s agricultural development. Rather, it will introduce coherent learning material and discuss some key issues identified by the vast number of past studies with reference to examples from China. Any recommendations made by this report should be regarded as either concrete actions for implementing current agricultural development strategies and policies in Tanzania, or as a complementary proposal to implement those strategies and policies. The report will serve the action learning team that includes Tanzanian senior officials, researchers, and representatives of farmer organizations.

46. Chapter 1 of this report compares performance of the agricultural sectors in China and Tanzania. It covers more than three decades in China and the available data from Tanzania. Chapter 2 analyzes the reasons why China has achieved a high level of agricultural growth and poverty reduction, but Tanzania has not. It compares poverty reduction in both countries and describes the reasons behind their contradictory performances.

47. Chapter 3 discusses the different performance of the agricultural sectors by using the state-market-farmer framework to examine what can make agricultural development more efficient, thus highlighting some key lessons Tanzania can learn from China. Chapter 4 offers policy suggestions.

1. Overall Performance of the Agricultural Sectors in Tanzania and China

1.1 Agricultural growth in China and Tanzania

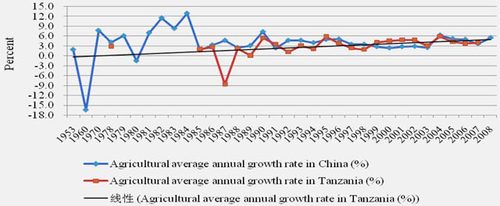

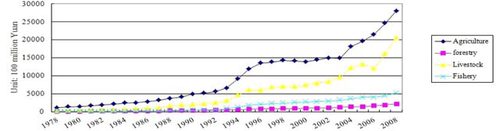

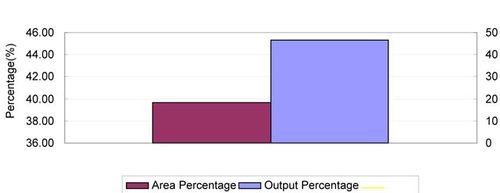

48. Despite significant development of the nonagricultural sector in China over the last 30 years and rapid development of the mining, tourism, and services sectors in Tanzania over recent decades, agriculture still plays a vital role in the social and economic life of both countries. More than 60 percent of Chinese and 85 percent of Tanzanians still live in rural areas, thus the agricultural sector is critical for growth and poverty reduction in both countries. Figure 1-1 shows trends of agricultural sector GDP growth over the last decades in China and Tanzania. Agriculture grew at about 2 percent from the 1960s to the 1970s in China, and then began to grow rapidly as economic policies were reformed. From 1978 to 1984, China experienced the highest agricultural growth in history, more than an average of 8.2 percent annually, for almost six years. The increases both in terms of output and value accumulated offset the decline and stagnation of agricultural GDP growth later on. China’s agricultural sector gained a higher growth rate again after 2004, and reached a 5.2 percent annual growth rate. Overall, China’s agricultural GDP grew at an annual average of 4.3 percent over the last 30 years.

49. At an average annual growth rate of 3.5 percent, Tanzania’s growth is lower than the 4.3 percent of China, but exceeds the Sub-Saharan African average of 3.3 percent. Growth in Tanzania’s agricultural GDP accelerated over the period, reaching an average rate of 4 percent from 1996 to 2003, which was even higher than China’s growth rate during the same period, and then declined after 2004. According to the Agricultural Sector Review Report, agricultural GDP grew 4.4 percent annually from 1998 to 2008 (MAFSC, 2008).

Figure 1-1. Average annual agricultural GDP growth in China and Tanzania

Source: China NBS and MAFSC of Tanzania 2008

50. The difference in agricultural performance is demonstrated by per capita agricultural GDP. Although the annual agricultural growth rate of the two countries does not seem like a huge gap after the beginning of the 1990s (Figure 1-1), China’s agriculture has performed much better by measuring per capita agricultural GDP, which

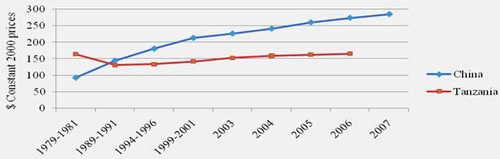

implies a significant productivity improvement. During the 1970s, China’s per capita agricultural GDP was less than US$ 100 calculated in constant 2000 dollars, while at the same time it was more than US$ 160 in Tanzania. China’s per capita agricultural GDP reached around US$ 200 in the 1980s, while in Tanzania it dropped to US$ 130. Although Tanzania’s per capita agricultural GDP began to increase after the year 2000, it only increased by 1.4 percent annually from about US$ 140 in the year 2000 to US$ 160 in 2007. During the same period, China’s per capita agricultural GDP increased by 3.3 percent from US$ 200 to US$ 270 USD (Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2. Per capita agricultural GDP of the agricultural population in China and Tanzania

Source: FAO, 1999

51. China’s per capita agricultural GDP began to surpass that of Tanzania only in the beginning of the 1980s, suggesting that on average the agricultural productivity of China’s rural labor force was lower than that of Tanzania before the 1980s. The increase of per capita agricultural GDP in China reflects a rapid development of China’s agricultural labor productivity. The two countries had the same level of agricultural productivity measured by

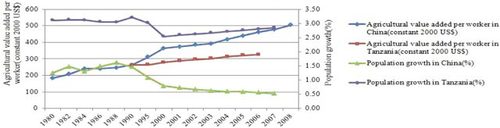

agricultural GDP in 1990, around US$ 264 per laborer, while in 2006, China’s figure was US$ 461 while in Tanzania it was only US$ 326 (Figure 1-3). Of course, population growth also partially explains the change in per capita agricultural GDP. In the 1980s Tanzania’s population growth rate was only slightly less than 1.5 percent, while it continued to grow at more than 3.0 percent during the 1980s, and remains at more that 2.6 percent after entering the new century despite the growth rate decline.

52. China’s population growth rate never exceeded 2.0 percent even in the highest growth rate year; the growth rate remained at 1.46 percent during the 1980s, declined to 1.0 percent during the 1990s, and continued to decline to 0.65 percent after the year 2000. Decreased population growth along with increased productivity contributed to the

increase of per capita agricultural GDP.

53. In Tanzania, however, the low growth rate in the agricultural sector has been largely offset by its phenomenal population growth, thus per capita agricultural GDP has not seen a significant increase given the assumption that factor productivity remains unchanged. The change in the agricultural productivity of labor in China and Tanzania partly explains the relationship between growth and poverty reduction in the two countries.

Figure 1-3. Agricultural value added per worker and population growth in China and Tanzania

Source: DATA of the World Bank

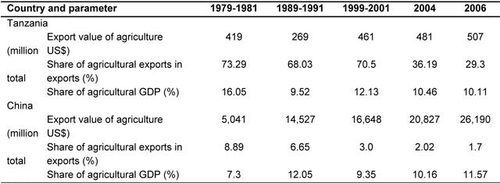

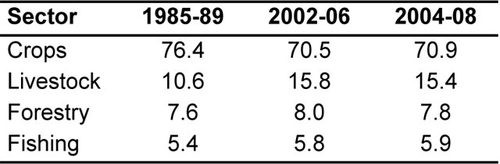

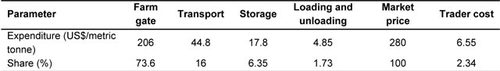

54. The comparison of per capita agricultural GDP in terms of absolute value shows that the Tanzanian figure is not substantially lower than that of China because the composition is different in the two countries. In Tanzania the export of cash crops with high value-added is a large percentage of the country’s agricultural GDP (Table 1-1). Agricultural exports accounted for about 73 percent of the country’s total export value and 16 percent of agricultural GDP during the period 1979 to 1981. During the same period, China’s agricultural exports only contributed about 8 percent to the country’s total exports and 7 percent of agricultural GDP. The contribution of Tanzania’s agricultural exports to total exports and agricultural GDP decreased to 29 percent and 10 percent, respectively, in 2006, which

implies that Tanzania is losing its traditional comparative advantage. China has been able to almost double the share of agricultural exports in its agricultural GDP compared to the 1980s, despite the sharp decline of its share of total exports because of the substantial expansion of other sectors.

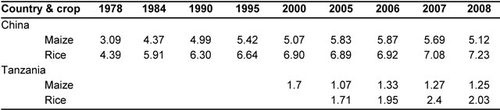

1.2 Crop production in China and Tanzania

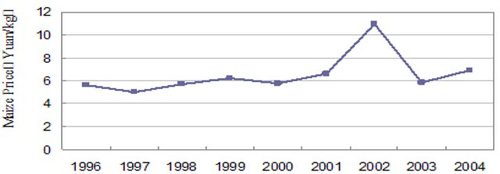

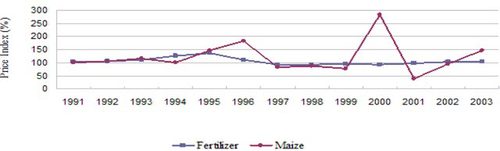

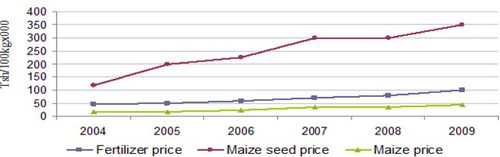

55. The output of major crops planted in China and Tanzania expanded over the last 30 years, however, the increases were much more significant in China than in Tanzania (Table 1.2). Volume as well as productivity was different. In China, increased land productivity for major crops was associated with productivity improvements. From

1978 to 2008, the maize yield increased from 2.8 metric tonnes per hectare to 5.6 metric tonnes. In Tanzania, after a gradual increase from 1.2 metric tonnes in 1978 to the highest level of 3.1 metric tonnes per hectare in 2001, maize productivity experienced decline and stagnation in recent years. With the sole exception of tea productivity, the

productivity of all crops in Tanzania has not seen a significant improvement over the same period of time. Notable gaps in major crop productivity can now be found between China and Tanzania (Figure 1-4). Increased output of major crops followed a different growth pattern. China’s crop production increased mainly because land productivity

improved even while arable land decreased because of rapid urbanization, while Tanzania’s major crop production improved largely based on area expansion (Figure 1-5).

Table 1-1. Share of agricultural exports to total exports and agricultural GDP, China and Tanzania

Source: FAO, 1999

Table 1-2. Production growth of main agricultural crops in China and Tanzania, 1978-2008 (growth factor)

Source: FAO, 1999

1.3 Contribution of agriculture to economic development in China and Tanzania

56. Agricultural development has made a remarkable contribution to the economies of both China and Tanzania, even though the share of the agricultural sector to the total economy has declined in both countries. In the 1970s, the share of the agricultural sector in the Tanzanian GDP was 49 percent, declined to 46 percent in 2002, and then dropped to 25 percent in 2008. In China, the figure was 28 percent in 1970s, but dropped to 11 percent in 2008 as (Figure 1-6).

Figure 1-4. Major crop productivity in China and Tanzania

Source: FAO, 1999

Figure 1-5. Comparison of per unit yield for principal agricultural crops in China and Tanzania (kg/ha) in 1999

Source: FAO, 1999

Figure 1-6. Sectoral contribution to GDP in China and TanzaniaSource: China Statistical Yearbook 2009, Tanzania Economic Survey 2008, DATA of the World Bank

57. Although growth of the agricultural sector in the overall Chinese economy has reduced dramatically as other sectors have expanded, the sector has been vital to economic growth, particularly during the initial stage of China’s

economic expansion (Figure 1-7). The overall growth rate was 7.6 percent in 1979, with agriculture contributing 1.6 percent and sharing 21 percent of the total growth rate. From the end of the 1970s to the middle of the 1980s is regarded as the stage when China’s rapid economic growth took off, with a significant contribution from the agricultural sector. The contribution of the agricultural sector to overall economic growth is much more significant

considering that industrial growth was substantially derived from agriculture-based rural township enterprises which were developed based on capital and raw material from agriculture. In this context, China’s rapid economic growth is actually based on agriculture. The share of agricultural growth to overall economic growth rate declined after 1985

with the rapid expansion of the manufacturing and services sectors in China.

Figure 1-7. Annual GDP growth rate and sector contributions in China

Source: Author's calculations, based on China Statistical Yearbook

58. Tanzania’s economy stagnated for a long time before the end of the 1990s, but entered a positive stage after the decade ended. Tanzania’s GDP grew by 4.8 percent in 1999, and agriculture contributed 1.3 percent or 27 percent of the 1999 growth. The contribution from agricultural growth was 14 percent in 2003, 21 percent in 2004, and 16 percent in 2008, but the agriculture contribution to overall economic growth has never exceeded 25 percent (Figure 1-8). Despite the relatively reasonable growth rate of the agricultural sector, its contribution to overall economic growth has not been significant, which partially explains the inconsistency between growth and poverty

reduction — the agricultural sector employs the majority of the country’s population, but has not contributed substantially to economic growth.

Figure 1-8. Annual GDP growth rate and sector contributions in Tanzania

Source: Author's calculations, based on Tanzania NBS

59. The contribution of agriculture to economic development is also demonstrated by its provision of capital and labor to other industries in addition to its direct contribution to the GDP. Before reform began in 1978, China adopted a strategy of “agriculture as the foundation, industry as the pillar” of the economy. In the process of centrally-planned industrialization, agriculture provided initial capital through the “price scissors”(agricultural produce price is controlled under the value) for industrialization. In the early years, 40 percent of the national financial revenue came from agriculture. According to incomplete statistics, Chinese farmers contributed US$ 100 billion for industrialization through the effect of the price scissors between 1953 and 1983.

60. In the command-and-plan regime, rural labor’s costs were kept low or even zero so as to produce a capital surplus. Rural labor still provided important inputs for the construction of rural infrastructure even after the reforms. The annual input of rural labor was of 7.22 billion workdays between 1989 and 2000. Since the 1980s and particularly the 1990s, the agricultural sector and farmers provided initial capital for industrialization through the “land scissors” (land price is controlled under the value) by which the value of land is captured by the urban and industrial sector. Moreover, migrating farmers have become the main labor force in cities. Farmer-workers migrating from rural to urban areas have accounted for 52.6 percent of the labor force in urban industries, 68.2 percent in manufacturing industries, and 79.8 percent in the construction sector. It is estimated that each migrating farmer produces US$ 4,000 of GDP per year, or US$ 1 trillion from the 200 million migrating farmers every year (Xu Hengjie, 2009).

61. In contrast, Tanzania’s agriculture has contributed little to industrialization because the country has no enforced policy to extract capital from agriculture for industrialization, nor could its agriculture produce sufficient surplus that could be transformed into a source of industrialization. Taking the largest growth period as an example, since 2000 agriculture has been growing, but insufficiently to balance the population growth. The net growth (agricultural growth rate minus population growth rate) was only about 1.5 percent, and meaningful surplus capital could hardly be generated from agriculture, therefore the agricultural sector was not able to significantly raise overall GDP. In China, the net growth rate in agriculture was almost 7 percent during the largest economic growth stage. In

addition, the relative labor scarcity in Tanzania also discouraged the development of labor-intensive industries, which unfavorably affected the contribution of agriculture to the economy in terms of labor and capital supply.

1.4 Contribution of agriculture to employment in China and Tanzania

62. No other sector has such a huge potential as agriculture to create employment opportunities and alleviate poverty (Lipton, 2001). Data show that agriculture is the main sector of the economy for labor absorption in both China and Tanzania. In 2007 the rural population was 62 percent of the total in China and 74 percent in Tanzania, while the share of those engaged in agricultural activities was 63 percent in China and 77 percent in Tanzania (Table

1-3). The contribution of agriculture to employment, however, has been decreasing in both countries.

Table 1-3. Comparison of agricultural population in China and Tanzania ('000)

Source: FAO, 1999

1.5 Contribution of agriculture to food security and poverty reduction in China and Tanzania

63. China’s per capita grain production reached 285 kilograms in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and then exceeded 300 kilograms in the following periods, except for 2003 when it decreased to 286 kilograms. In 2007, China’s total grain output reached 501.5 million metric tonnes and per capita grain production reached 379.6

kilograms, enough to meet the demand for the current population. As measured by FAO’s food security standards, China’s grain output totaled 501.5 million metric tonnes in 2007, net cereal exports were 7.96 million metric tonnes, and net soybean imports were 30.82 million metric tonnes, while the self-sufficiency ratio for grains (including soybean) exceeded 95 percent, meaning that per capita grain production would be 400 kilogram when divided by a population of 1.3 billion. If non-cereal crops are included, then food security levels have been very high. From the middle of the 1980s, China became a net food exporting country, and from the middle of the 1990s, China again began becoming a net food exporter (Huang Jikun, 2008). The stock consumption ratio at the end of 2006 stood at around 35 percent and was estimated to be 40 to 45 percent at the end of 2007.

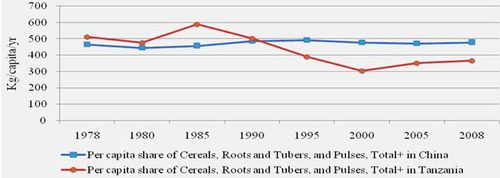

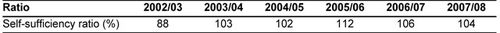

64. According to encouraging data, during 2003 to 2008 Tanzania was self sufficient in food at an average of 102 percent, among the highest internal food producers in Africa (MAFSC, 2008). However, in the long run, both per capita cereals and non-cereals have declined. Tanzania’s per capita cereal production was 156 kilograms in 1978, while in 2008 it was only 146 kilograms. In 1978 non-cereal production was 334 kilograms, while in 2008 it was 201 kilograms (Figure 1-9).

Figure 1-9. Per capita share of cereals, roots, tubers, and pulses in China and Tanzania

Source: Author's calculations, based on FAO, 1999 and DATA of the World Bank

2. Agricultural Development Has Led to Growth and Poverty Reduction in China, But Not in Tanzania

2.1 Looking at the data

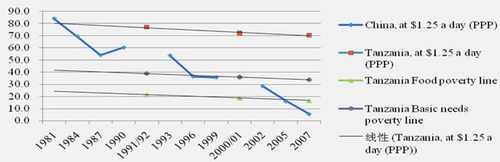

65. China’s economic growth is closely associated with poverty reduction. The poverty incidence has fallen from 84 percent in 1981 to 5.4 percent in 2007 as measured by the World Bank’s US$ 1.25 PPP (Ravallion. 2007) (See Figure 2-1). The annual poverty rate has declined by about 2.62 percent over the last decades. Poverty-growth

elasticity has even been around 2.7 percent from the 1980s until the last decade according to different calculations (Li Xiaoyun, 2010). Every 1 percent of economic growth has led to almost a 2.7 percent decrease in the poverty incidence of China over the last 30 years, which makes China’s growth model uniquely pro-poor.

66. Despite its poor performance during the 1990s, the economy of Tanzania expanded rapidly after the turn of the century, and annual GDP growth almost doubled over the last decade from 4.1 percent in 1998 to 7.4 percent in 2008. Since 2000, GDP growth averaged about 7 percent annually (Poverty and Human Development Report, 2009). At same time, Tanzania’s agriculture grew by 4.4 percent from 1998 to 2008 (MAFSC, 2008). It is relatively higher than the record of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 2-1. Incidence of poverty in China and Tanzania (%)

Source: China’s Poverty Evaluation Report; Household Budget Survey 2007 (NBS, 2009), Johannes Hoogeveen and Remidius Ruhinduka calculations. The developing world is poorer than we thought, but no less successful in the fight against poverty

67. However, the high economic growth of Tanzania has hardly affected poverty. The national poverty headcount fell only by 2.1 percent, from 35.7 percent in 2000/2001 to 33.6 percent in 2007, with an equally modest decline in rural and urban areas (Hoogeveen. 2009). Food poverty dropped from 21.6 percent in 1991/1992 to 16.6 percent,

only a 5 percent reduction over 15 years, whereas basic needs poverty dropped from 38.6 percent to 33.6 percent during the same period of time (Poverty and Human Development Report, 2009). The country’s poverty-growth elasticity was at most 0.76 during the 2001 to 2007 period, meaning that 1 percent of growth could only bring about a 0.76 percent decline in poverty. Not only has the income poverty and nutritional status of households not improved substantially, but the share of the population with insufficient calorie consumption declined only marginally from 25.0 percent to 23.5 percent from 2001 to 2007 (World Bank, 2009).

68. As with poverty, these poor outcomes raise concerns about why rapid economic growth has not translated into much greater improvements in poverty reduction and nutrition. The weak povertygrowth elasticity and inconsistency among growth,poverty, and nutrition trends underline the decoupling of growth and poverty reduction (Pauw and Thurlow, 2010). It is therefore useful to understand why China’s growth has led to rapid poverty reduction while Tanzania’s has not. With such an understanding, we can use experience and lessons from China’s development success to improve growth and poverty reduction efforts in Tanzania.

69. Poverty declined mostly during the time when both the overall economy and agricultural sector grew rapidly in China (Figure 2-1). The country was dominated by the rural population at the time, so reducing rural poverty was urgent for overall poverty reduction. The rural poverty incidence measured by China’s national poverty line

declined from 30.1 percent in 1978 to 15.7 percent in 1984, while farmer income increased by 16.5 percent annually (Huang Jikun, 2008). During the same period, agriculture grew from 4.1 percent to 12.9 percent, at an average rate of 8.0 percent (Huang Jikun, 2008), the highest recorded in the country’s history, which implies a strong relationship

between agricultural growth and poverty reduction. The poverty-agricultural sector growth elasticity in China was 2 percent after the 1980s. Despite a decline of the share of the sector in the whole economy, the agricultural sector is still a vital factor for poverty reduction in China. The povertyagricultural growth elasticity was 1.51 percent, the poverty-industry elasticity was 1.07 percent, and the service sector was 0.97 percent during 2000 to 2008 (Li Xiaoyun, 2010). China’s economic growth, therefore, is based on agriculture and pro-poor growth.

70. Tanzania’s agriculture accelerated at an average rate of 4.4 percent during 1998 to 2008, but only slightly higher than 3.3 percent during the time before 1999. With 2.9 percent population growth, agricultural growth has not reached a sufficient pace to foster overall growth and poverty reduction. Even reaching the current gross 5 percent agricultural growth rate target, it is still difficult to generate a critical mass to offset rapid population growth and

produce a surplus to stimulate growth — the net agricultural growth rate is only about 3.1 percent compared with more than 6 percent in China. That is too low to make agriculture the driving force for poverty reduction. The country had an overall encouraging growth rate of 6.3 percent from 1998 to 2008 and a per capita GDP rate of 3.3 percent, so

the 1.4 percent of per capita agricultural GDP rate was much lower than the population growth rate and agricultural labor growth rate of 3.8 percent (Figure 2-2).

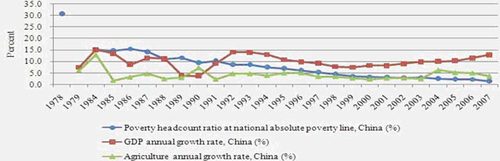

Figure 2-2. Annual GDP growth rate, annual agricultural growth rate, and poverty headcount ratio at national absolute poverty line, China

Source: NBS, China

2.2 Importance of economic structure and growth patterns

71. In addition to the effects of population growth, the different growth patterns followed by China and Tanzania largely explain the relationships between growth and poverty in these two countries. Although poverty could theoretically be effectively reduced either by growth or by distributing the benefits of growth, nonetheless, growth is still a primary source of poverty reduction. It would be very costly to rely on distribution to reduce poverty because this approach requires a developed institutional framework and capacity that are usually not found in most developing counties.

72. If growth is to be effective for poverty reduction, it must be pro-poor, and for such growth to take place, the sector that employs the majority of the poor should make a great contribution to growth. China’s remarkable poverty reduction was accompanied by high economic growth and rapid agricultural growth, particularly the per capita growth

rate. By using the national poverty standard, rural poverty incidence dropped from 30.7 percent in 1978 to 14.8 percent in 1984, and further to 1.6 percent in 2007. About 50 percent of the rural poor were removed from poverty from 1978 to 1984.

73. This time period experienced the highest economic growth as well as the highest agricultural growth in China. The agricultural sector contributed more than 35 percent of the GDP growth rate during this time. Although industry in China grew rapidly and contributed to a large percentage of the entire economic growth rate, a substantial part of the industrial growth rate originated with agriculturebased rural enterprises that mainly employed farmers and the raw materials from agriculture — agriculture indirectly and effectively contributed to industrial growth.

74. The share of total production value from rural enterprises to total industrial production value expanded from less than 9.1 percent in 1979 to 20 percent in 1985, and farmer net income increased 132 percent during these six years (Huang Jikun, 2008). The contribution of agriculture to total GDP began to decline and thus the economic structure began to transform. This broad-based growth pattern suggests that for countries where the rural

population and agriculture are dominant — such as China and Tanzania — they must focus on effective agricultural growth and entire economic transformation to reduce poverty.

75. Tanzania experienced high economic growth from 2001, from 4.1 percent in 1998 to 7.4 percent in 2008, along with a modest structural change that was accompanied by only a small change in poverty reduction (MFEA, 2009). A positive trend in terms of growth and structure changes did not result in expected poverty reduction. Over 10 years, as the largest sector that employed more than 60 percent of the total labor force, the agricultural sector’s contribution declined from about 29 percent in 1998 to 24 percent in 2008 (MFEA, 2009). Poverty reduction is usually highly associated with the decline of the agricultural share in the entire economy.

76. In China, the provinces with a slow change in the economic structure usually had a lower poverty reduction rate (World Bank, 2001). The decline in the share of agriculture to total GDP in Tanzania was the largely the result of poor productivity. In fact, the agricultural growth rate only contributed on average less than 20 percent of the total economic growth rate from 2001 to 2008, which was much lower than the 35 percent contribution that China’s agricultural growth rate made during the period of highest economic growth. Although overall growth rates after 2001 were much higher than in the 1990s, from 1986 to the end of 1990s agriculture grew from 3.3 percent to 4 percent,

which shows a weak relationship between economic growth and agricultural development (World Bank, 2000).

77. The growth in agriculture is substantially limited by its forward and backward links. Lack of agricultural supplies and food processing capacity restricted transportation and other services, which made it difficult for agriculture to grow rapidly, even ignoring the negative impact of population growth. At the same time, the country’s economy was dominated by the services sector, accounting for more than 45 percent of GDP. Since 2000, the sector has grown at an average 7.6 percent annually, which is higher than agricultural growth and close to the level of overall economic growth. However, the sector is neither labor intensive nor requires lowskilled labor, and thus it has not created many employment opportunities for rural people.

78. The industrial sector contribution to GDP grew slowly from 25.2 percent in 1998 to 28.2 percent in 2008. Mining has been the most dynamic sub-sector, expanding rapidly at an average growth rate of 15 percent annually from 2000 to 2007, which could attract labor. The links between the mining sector and local supply chains that could

create employment opportunities have been weak (MFEA, 2009). Manufacturing only grew from 8.4 percent in 1998 to 9.4 percent in 2008, which is insufficient to create a large number of jobs. The construction sector also grew and might have contributed employment, however, slow growth and its small scale in comparison to the overall economy

limited its contribution to employment.

79. The sectors that had higher growth rates in Tanzania during a time of rapid economic growth were those not able to generate significant employment. Agriculture is the sector that employs a large part of the labor force, but its growth rate has been largely offset by increases in population and the labor force.

80. Those sectors with a high growth rate, such as a rapidly growing service sector (7.5 percent annually), have not contributed to a substantial increase in the GDP because subsectors such as communications contributed little to the economy and could also not generate sufficient employment opportunities. They are not labor intensive and do not employ labor with a low skills. Even those sectors that provided employment such as mining and construction — which have been the most dynamic — did not significantly affect poverty because their share of the overall economy is very small.

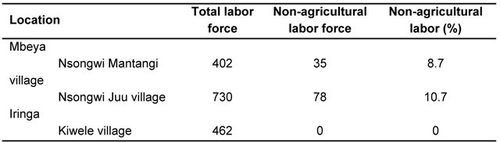

81. During the last 10 years, although the country has employed on average 630,000 people per year, employment has been primarily in small informal businesses, which typically have low earnings and productivity (MFEA, 2009). A rapid field study by the authors in Mbeya, Iringa, and Morogoro indicates that significant rural-urban

migration has not occurred over the last 10 years (Table 2.1). The interviewed farmers said that they could earn about TSH 40,000 monthly in the city, but there was nothing left to save. The poverty assessment for the country shows that the slight income growth for the rural poor had a large effect on overall poverty in Tanzania. The movement of households out of agriculture has also played a strong role in poverty reduction — acceleration of national poverty reduction can be achieved only through an accelerated decline in poverty in rural areas (Hoogeveen et al., 2009).

Table 2-1. Non-agricultural labor in three villages in Mbeya and Iringa, Tanzania

Source: Field visits

82. It is clear that during the high economic growth period, China’s rapid economic growth was largely based on agriculture and agriculture-related sectors, and national poverty reduction was largely based on poverty reduction in rural areas. Tanzania’s relatively high economic growth was obviously disconnected from agricultural growth,

and poverty reduction in urban areas such as Dar es Salaam only had a minor effect on national poverty reduction because of a relatively small urban population. This raises a question — was the effort made by the Tanzanian Government after the end of the 1990s to reduce poverty on the right track, and was the plan to develop agriculture as an engine of growth and economic development effective?

83. China and Tanzania started their rapid economic growth under different income distribution levels, which also affected poverty reduction efforts. When Tanzania’s economy began to grow rapidly after 2000, its Gini coefficient was already 0.35. This provided Tanzania with much less space for growing than China, which had a Gini coefficient of about 0.1 at the end of the 1970s. However, the inequality remained unchanged over the last eight years, 0.35 from 2000 to 2007 (MFAE, 2009), which provided a positive basis for the country’s further growth, particularly pro-poor growth. Despite the much larger increase in inequality in Dar es Salaam, poor households gained more than in other areas where the inequality increase was more modest (Hoogeveen et al., 2008). Increasing overall income growth across the country in poor households should still couple growth and poverty reduction.

84. Overall, it is the agriculture-based economic structure with backward and forward links and a pro-poor growth pattern that has allowed remarkable poverty reduction in China. In Tanzania, the problem of economic structure and growth patterns prohibits the poor from benefiting from growth. Experience in both countries suggests that growth should bring significant structural transformation, otherwise poverty will not be reduced efficiently. The sectors within the economy should be connected in order to avoid “isolated growth islands”, otherwise growth will be substantially limited and employment will not improve significantly. For rapidly growing sectors to have an impact on poverty, they should promote either those sectors that have already employed high numbers or those that can attract a large-scale labor force. Finally, generating a growth chain rather than a growth island is essential for linking growth and poverty reduction. To do so, it is necessary to create links within the economic structure to fully utilize local resources and create employment opportunities. 85. To adjust the economic structure, it is important to promote the right growth pattern. A consistent relationship between growth and poverty happens only under the conditions.

• With a large population engaged in agriculture, a very high agricultural growth rate that produces a surplus must be promoted so that the surplus over consumption can be traded to either domestic or international markets. (China fits the former case, while Tanzania could exploit both markets given its high potential in agriculture and relatively low domestic market demand.) At the same time, lower food prices for consumers will reduce the cost for industrial and services sector development because lower wage could be maintained in urban and industrial sectors.

• There should be opportunities that can attract capital from the agricultural surplus. Those opportunities could be in either manufacturing or other sectors that should be able to absorb laborers from agriculture.

• Countries like China in the early 1980s or Tanzania today usually have insufficient domestic capital for the economy to take off, thus foreign investment can significantly accelerate this process. Tanzania’s economy has been growing in different isolated islands while the level of agricultural growth has been too low to generate critical mass to produce a meaningful surplus, taking into account the rapid population growth. Therefore, the country’s growth pattern must focus on agriculture. Unless agriculture can be linked with other sectors, poverty will not be significantly reduced.

2.3 Importance of agricultural structure and growth patterns

86. No country in the world has proven that an economy with a large agricultural population could be developed without first developing the agricultural sector. It is not sufficient to rely only on agriculture to develop the entire economy without structural transformation, but it is certainly essential to focus on agricultural development for a certain period, ideally in the beginning of the economic take off. To develop the agricultural sector, particularly smallholder-based agriculture as in China and Tanzania, structure and growth patterns in the sector are the most important factors affecting agricultural development and poverty reduction.

87. China’s experience suggests that for agriculture to be pro-poor it needs to go through stages:

• Food crops planted by the majority of smallholders needs to be developed rapidly both in terms of quantities and growth rate to provide food security and generate a surplus for income generation.

• Crop structure within family farms needs to be diversified from one dominated by food crops to mixed food crops and cash crops to increase farmer income, unless smallholders can create a large-scale specialized farm.

• The agricultural structure needs to be further developed, moving from farming into crop-livestock and other agricultural occupations such as fishing to further increase farmer income. This is part of the reason why average farmer income in China increased from RMB 133 in 1978 to RMB 355 in 1984 these seven years (Huang Jikun, 2008).

• A substantial increase in farmer income requires transformation of the whole economy so that it can provide laborintensive sectors to attract labor from agriculture. For example, the labor force engaged in agriculture in China dropped from 97 percent in 1980 to 82 percent in 1985 to 59 percent in 2005 (Huang Jikun, 2008).

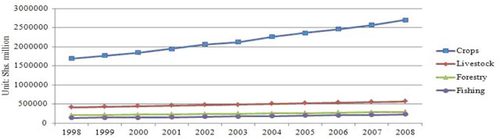

88. Seventy-four percent of Chinese farmers are engaged in farming and livestock production, and food crops have been the major focus of smallholders. Livestock is the second most important sector for Chinese farmers. Fishing is also a source of income for farmers, while forestry is mainly managed by the state forestry farms. The

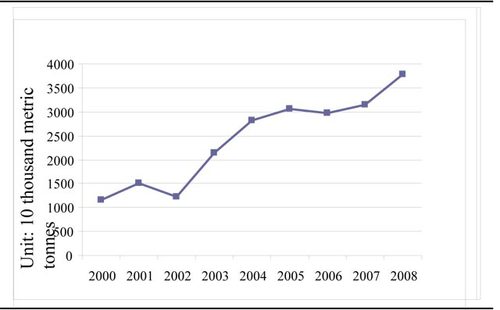

total value of crop production is much higher than that of livestock, fishing, and forestry (Figure 2-3). Within the agricultural sector, the value of crops and livestock has grown the most over the last 30 years.

89. In Tanzania, farmers mainly engage in crop production and livestock; fishing and forestry are usually managed by relatively large business corporations, although fishing can be the main income source for the rural people in coastal and lake areas. Livestock are kept by 37 percent of households. The value of crop production in

Tanzania far exceeds that of livestock, forestry, and fishing (Figure 2-4).

Figure 2-3. Production value of agriculture, forestry, livestock and fishery, China

Source: NBS, China

Figure 2-4. Gross domestic product by type of economic activity (at constant 2001 prices), Tanzania

Source: NBS, Tanzania

90. Within the crop production sector, rice and wheat are usually the most important sub-sectors for Chinese farmers, with rice mainly found in southern areas and wheat in the northern part of the country. Cotton is only grown in northern areas of China, while maize is distributed relatively widely in the country. Major crop production is actually dominated by family farms in rural China because crop production output and planting area on large state farms is limited.

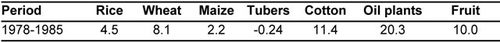

91. Over the last decades, particularly after the 1978 to 1984 period, the output of rice, wheat, and maize expanded significantly in China (Figure 2-5). Among the major food crops in China, rice grew by 4.5 percent, wheat 8.2 percent, maize 2.2 percent, annually from 1978 to 1984. In terms of total output expansion and growth rate, wheat was significantly driving the major food crop production increase in China. Rice production followed a similar trend, but less significantly than wheat. The growth of both wheat and rice has implications for household income because they were grown widely by the rural poor during the 1978 to 1984 period. Cash crops such as cotton and oil seeds also grew at 11.4 percent and 20.3 percent, respectively, which had a higher poverty impact, but was limited due to their narrow geographical distribution. Fruit production grew at 10.0 percent with wide distribution across the country, but is mainly grown by relatively wealthy farmers (Table 2-2). During the rapid economic growth period in China, agricultural growth was broad-based but driven by different sub-sectors, which led to different poverty effects. Wheat and rice were the most important factors to link the growth of food crop production and poverty reduction.

Figure 2-5. Output of rice, wheat, maize, cotton, oil plants, and fruit in China

Source: NBS, China

Table 2-2. Average annual growth rate of main crops in China (%)

Source: Author’s calculations, based on NBS, China

92. From 1998 to 2008, food crop production in Tanzania increased by 3.9 percent per year on average. Over these 10 years, cassava was the largest contributor to production quantities at 31.6 percent, maize 17.6 percent, potatoes 16.7 percent, banana 16.45 percent, paddy 6.5 percent, and pulses 5.0 percent (MAFC, 2008). However, more than one-half of the total harvested area is allocated to cereals, of which maize is the country’s dominant

staple food crop (Paul and Thurlow, 2010).

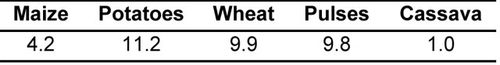

93. Maize shared 36 percent of the total food crop planting area and involved over 80 percent of Tanzanian farmers, whereas wheat is produced almost exclusively by large-scale commercial farms in the Northern Zone. Rice is becoming an important crop for smallholders in the Western and Lake Zones (Paul and Thurlow, 2010), but shared a smaller percentage of production quantities and planting area. For the last decade, all food crops have expanded, but at different rates. The highest sub-sectors were potatoes, wheat, and pulses, while cassava and maize grew more slowly (Table 2-3).

94. Potatoes, wheat, and pulses drove growth of food crop production from 1998 to 2008, but not maize and cassava. All major traditional cash crops also grew at a relatively high rate. Cotton grew at 11 percent, both sugar and tobacco grew at 9 percent,and cashew grew at 7 percent (MAFC, 2008). These crops, however, are highly concentrated in specific regions. Both cotton and tobacco are smallholder crops, but limited in some regions, while sugar is mostly produced by large-scale commercial farmers (Paul and Thurlow, 2010). With this growth pattern,

the sub-sectors that include a majority of smallholders have unfortunately been excluded from high growth. Thus the growth of crop production benefits certain regions or groups, rather than the whole country.

Table 2-3. Production trends, average annual

Source: MAFC, 2008

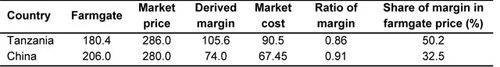

95. Above all, during the initial stage of economic growth in China from 1978 to 1984, agricultural growth and particularly crop production highly favored smallholders. The country’s high economic growth rate was accompanied by high growth rates for agriculture, food crop production, wheat, rice, farmer income, along with a high rate of poverty reduction. Tanzania has maintained an economic growth rate of more than 6 percent since 2000; however, poverty reduction was only 2 percent over the years. The economic growth rate has not been accompanied by the necessary growth rate for agriculture, crop production, and leading crops such as maize. Rather, the sectors that grew rapidly did not result in effective employment increases, and the sub-sectors that grew rapidly within agriculture are not the ones are usually occupied by the majority of smallholders in the country. Therefore, the country’s low poverty-growth elasticity can be regarded primarily as a result of the current structure of agricultural growth, which favors large-scale production of rice, wheat, and traditional crops, rather than crops from which the largest number of smallholders in the country can benefit such as maize and cassava (Paul and Thurlow, 2010).

2.4 Importance of structural changes

96. For growth to be pro-poor not only requires growth, but also continuous structural transformation. China’s rapid poverty reduction follows three steps of structural changes that provide a powerful engine for continuous poverty

reduction over time.

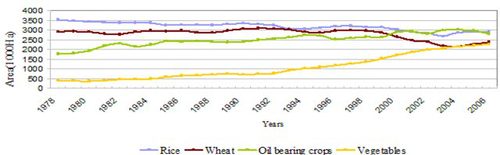

97. First, from 1978 to 1984, China experienced rapid increases in production of food crops, cash crops, and livestock. The structure of crop production and agriculture began to change from being centered on only food crops to a system centered on food crops, cash crops, and livestock. The share of crop production value to total agriculture production value dropped from 80 percent in 1978 to 69 percent in 1985, while livestock increased from 15 percent in 1978 to 22 percent in 1985 (Table 2-5). Within crop production, cotton, oil seeds, sugar, vegetables, and fruit all experienced a rapid increase in planting area and yield. Food crop production increases mainly from productivity increases, not area expansion. Area expansion was mainly for non-food crops (Figure 2- 6). This period experienced the highest growth rate in farmer income in real terms (Table 2-5).

Table 2-4. Farmer perceptions about income changes over the last five years in two villages in the Morogoro region (% of farmers), Tanzania

Source: Field study data by author

Figure 2-6. Changes in planting area for rice, wheat, oil bearing crops, and vegetables, China

Source: Author's calculations, based on FAO, 1999

Table 2-5. Changes in agricultural structure, China (% of total agriculture production value)

Source: China's rural reform for thirty years, China Agriculture Press, Song Hongyuan, 2008, page 209

98. Second, from 1984 to 1988, the area for non-food crops continued to expand along with further productivity improvements for major staple crops. Third, after 1984, the entire rural economy began to transform. Rural township enterprises started as the engine for economic growth. Rural enterprises attracted 146 million laborers from rural

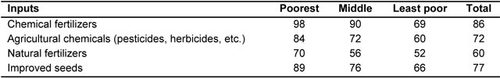

areas, while farmer income from rural enterprises increased from RMB 11 per capita in 1984 (8.2 percent of farmer income) to RMB 1,666 in 2006 (46 percent). Rural enterprises have become the major source of farmer income in rural China (Song Hongyuan, 2008).