2011.07-Working Paper-Rural Labor Migration and Poverty Reduction in China

Rural Labor Migration and Poverty Reduction in China

CAI Fang DU Yang WANG Meiyan1

I. Introduction

he fast growth of China’s economy in the past three decades is a historical phenomenon in the history of world economy. It is the fast economic growth that lays foundation for China to improve the wellbeing of one fifth world population and achieve the largest poverty reduction in the world. In fact, both economic growth and economic reforms have taken place in China simultaneously. The changes in the socioeconomic system have been important forces driving economic growth, and also, the inevitable outcomes of economic development.

China has kept correcting the distorted economic system during its economic development. Prior to the reform, China tried to achieve full employment and implemented comprehensive social welfare system biased towards urban residents by excluding rural residents. Labor allocation segmented between rural and urban areas was to guarantee the strategy of prioritizing the development of heavy industries. However, the segmentation implemented

in planning the economic system was harmful to the economic development in China.

First, the dual economic policies resulted in low economic efficiency of resource allocation. When the labor market was segmented between rural and urban areas, the rural surplus labor would not be able to move to industrial sectors and urban areas. The segmentation caused a distorted economic structure, as evidenced by slowly declining share of primary sector in national economy and low level of urbanization. More importantly, it resulted in the lag of employment shift with respect to value added shift in economic restructuring. The share of value

addition in agriculture in GDP declined to 28 percent in 1978 while the employment share in agriculture was still as high as 70.5 percent at that time.

The segmentation also created inequality of the distribution of economic resources between rural and urban areas. In 1978 there were 95 million people employed in urban sector and 310 million in rural areas, and the ratio of labor force between the two areas was 1: 3.2. In the same year, the total value of fixed assets in State Owned Enterprises totaled 448.8 billion yuan while the amount was 95 billion yuan in agriculture, and the ratio of capital

between two areas was 4.7:1. According to the law that production factors move to the sectors with higher marginal returns, the above case means efficiency loss of resource allocation.

Second, the implementation of those policies resulted in disincentive of labor input. Due to the fact that comprehensive employment was guaranteed in urban areas, urban residents who held urban local hukou (registered permanent residence) did not feel the unemployment pressure, which is called iron bowl.

Third, urban biased welfare system excluded the rural residents out of the social protection system, which not only increased the inequality and social conflicts between rural and urban areas but also mixed up the functions of enterprises in operation and social services.

Rural to urban migration plays an active role in correcting the above distortions. The classic theory in development economics affirms that reallocation of labor from traditional sectors to modern sectors reflects a shift from dual economy to modern economy. The rural to urban labor migration in China is regarded as the largest migration in human history (Roberts, 2006). Several factors contribute to this movement.

The first one is the so called compensation effect. Due to long existence of segmentation between rural and urban areas, the development in two areas has been imbalanced for a long time. In this regard, the rural to urban migration since the reform could be taken as compensation to previous distortions.

The second one is the development effect. China has witnessed the fastest economic growth in the world in the past three decades, which has accompanied the changing relationship between rural and urban areas. Meanwhile, this process is bound to break the speed of migration at normal speed.

Third, because massive rural labor forces were concentrated on limited land prior to the reform, labor productivity in agriculture was very low at that time which produced a big push for migration. Therefore, rural to urban migration will last for a long time in China.

The role of migration in poverty reduction is quite simple and direct. In general, the poor areas are constrained by endowment scarcity, for example capital scarcity. In remote areas, it is quite usual that poverty is associated with bad natural conditions. In this case, human resource is the most important production factor for many poor households. Poor households may escape those constraints and make use of the labor market in different places through labor mobility across regions. In addition to remittance, migration per se is a process to accumulate human capital while the latter is an essential factor to drive the economic development in less developed areas.

The paper is organized as follows. Chapter 2 reviews the process of rural to urban migration, in particular, the new phenomenon emerging in recent years. Chapter 3 introduces labor migration policies and their changes. Chapter 4 discusses the role of migration in economic development and poverty reduction. Chapter 5 explores the challenges of labor migration under the new situations. Chapter 6 sums up the experiences and lessons of migration policies in the past three decades and highlights the relevance of China’s learning to other developing

countries.

II. The Progress of Rural Labor Migration

2.1 Rural labor migration since the reform

Prior to the reform, rural labor forces were mainly employed in agriculture. In 1978, there were 285 million rural labor forces employed in agriculture, accounting for 70.9% of total labor forces in China and 92.9% of total rural labor forces. With pursuance of the rural reforms and, afterwards, urban reforms, the size of rural to urban migration has been driven by industrialization and urbanization and kept increasing. In recent years, migrants have been playing more and more essential roles in the urban labor market. Unlike many other developing countries, however, the rural

to urban migration has been featured by circulating migration due to the segmentation rooted in the hukou system.

At the early stage of the reform, the total amount of migration was very limited, around 2 million and being composed of craftsmen such as carpenters, bricklayer etc., or some self-employers. They moved within rural areas at that time. With improving labor productivity in agriculture and relaxation of regulations on mobility between rural and urban areas, the rural labor forces started moving towards cities or other regions. Meanwhile, the size of migration has been increasing. By the end of 1980s, total number of rural migrants reached more than 30 million. A significant flow of rural to urban migration began to appear.

Since 1992, after Deng Xiaoping delivered his famous speech, the Chinese economy started another round of fast growth. Because of fast expansion of non-agricultural sectors, a large number of rural labor forces moved across regions. At that time, the coastal areas sped up their opening-up and FDIs they attracted created nonagricultural

employment opportunities that pulled more and more rural labor forces moving out of agriculture. In 1993, the total number of migrants moving out of townships/villages reached 62 million, which doubled the number of four years earlier.Afterwards, the total number of rural migrants has been increasing year by year.

In the mid-1990s, the urban labor market faced serious situations due to SOEs restructuring and reforms in urban employment system, which led to massive unemployment and lay-offs. As a response, local governments in cities were inclined to implement strict employment protection by excluding migrant workers as many as possible.

Meanwhile, with coming of Asian Financial Crisis, the development of labor intensive industries in coastal areas slowed down in the changed international trade environment. Influenced by those factors, the speed of rural labor migration reduced during the period and the annual net increase of migrants decreased to 3.6 million, while the total

number of migrants still increased each year.

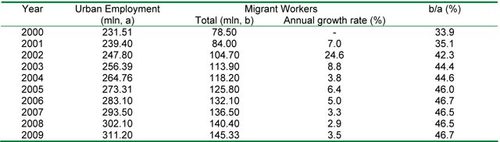

After China’s entry into WTO, the competitive labor intensive industries have been developing quickly, which further induced the demand for rural migrants. As indicated in Table 1, migrant workers have been an indispensable part of urban employment. In 2009, migrant workers accounted for 46.7% of total urban employment.

Regardless of the magnitude of migrant workers in urban labor market, their status of social protection and wellbeing are a matter of great concern. Regarding to the reforms in welfare systems, it is hard to say that success has been achieved as almost half of the workers are excluded from the system.

Table 1 Total Urban Employment and Migrant Workers

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China Statistical Yearbook (various years), China Statistics Press;

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China Yearbook of Rural Households Survey (various years), China Statistics Press.

2.2 Exhaustion of young labor forces

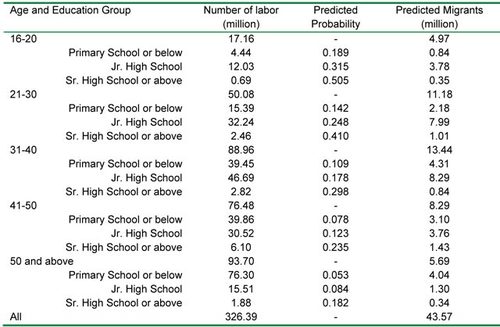

Young labor forces are the main component of transferred rural labor working in non-agricultural sectors. For instance, in 2003, migrants aged 40 or below accounted for 85.9% of total transferred rural labor. In 2009, the percentage was 83.9%. Therefore, the individual characteristics might be the most important factors that determine migration decision.

Taking advantage of the 1% population sampling survey conducted in 2005 by NBS, we estimated a Probit of migration decision for rural residents. In the model, individual characteristic variables are included, such as gender, age, educational attainment, and health status. To reflect on the impacts of regional factors, provincial dummies are

included to capture the variations across regional labor markets.

Based on predicted probability for each individual, it is possible to observe the average probability of various groups with different characteristics. Considering that age and education are the most important two determinants, we estimate average group probability by age and by education, as shown in Figure 1. The figure depicts the following two trends. First, within the same age group, people with more years of schooling have higher probability

to migrate. Second, within the same education group, the migration probability declines with age increase. Therefore, the studies ignore the role of age and education in migration decision which might overestimate the total number of surplus labor.

Figure 1 Predicted Probability by Age with Different Level of Human Capital (education)

Among those who stay in rural areas for more than half a year, the labor forces working in agriculture have more potentials to migrate. In other words, this group of people is the main source of rural surplus labor. The probability of migration is predicted based on individual characteristics. According to the predicted individual probability, we may calculate the average probability for each age group at various level of educational attainment. Multiplied by the total number of labor at each age group and each level of education with average probability, it

will give the potential number to migrate in each group categorized by age and education. Table 2 presents the distribution of 326 million agricultural workers by education and age group, and the average migration probability and total number of farmers are also depicted.

Table 2 Rural Labor Forces and Migration Probability

First, it is easy to find an uneven age distribution among 326 million farmers, which is consistent with our previous studies (Cai, 2007). Among rural labor forces engaged in agriculture, 52.1% of them are 40 or above and 28.7% are 50 or above. It is obvious that the remaining rural laborers are aging. In contrast, young labor forces working in agriculture are quite limited. Among those aged 30 and below, 20.6% of them work in agriculture. The rural labor forces aged 30 or below accounted for 22% of total rural labor forces in 2005.

Second, if the demand of agriculture for labor and labor market institutions do not change significantly, the total number of laborers to migrate will be very limited. As Table 2 shows, the total surplus labor is around 43.57 million. This is a consistent finding with Cai and Wang (2007) who use different ways to measure the total surplus labor. If China keeps similar growth rate and employment elasticity, in the coming few years, the labor shortage that has

already taken place will be more serious than the present.

In addition, regarding the future source of labor supply, an inverted-U shape pattern is seen between migration probability and age. Although the laborers aged 30 or below have high probability to migrate, the number remaining in agriculture for this age group is very limited, and the potential number for migration is even less, around 16 million. In contrast, there are a relatively large number of old (40 or above) labor remaining in agriculture, but they tend to have low educational attainment and low probability to migrate, which gives the number of potential migrants in this group at around 13 million.

III. Policy Evolution on Rural to Urban Migration

In a typical way of reform in China, changes in migration policy have been characterized by gradualism too. Starting from labor reallocation within agriculture, through labor mobility within rural areas, and rural to urban migration, China has witnessed the process of both removing the barriers to labor mobility and labor market development. It is this transitioning feature that makes Chinese institutional changes unique.

Labor mobility in China has mostly been driven by income disparities across regions. In addition to income gaps, migration costs and labor market environment have affected rural to urban labor migration too. One has to bear in mind that the rural labor migration would not develop in such a large size when strict institutional barriers were kept constant. With relaxing hukou system, the institutional reforms have taken place across regions, between rural and urban areas, and also within the urban labor market, which resulted in labor market integration in China. In turn, the labor market changes affect the macro economy and aggregated employment, which induces the adjustment for employment policy that may translate into migration policy.

In fact, the focus and orientation of employment policies have not been stable over time. In specific terms, the reform of migration policies could be phased in the following stages, including stricter restrictions, permission to migrate, slowing down the Unbridled Flow, guiding migration flow, and friendly treatment to migration.

Strict Restrictions: 1979-1983

At the early stage of the reforms, although the farmers were empowered with the right to make decisions on agricultural production, labor mobility was still restricted, in particular, between rural and urban areas. At that time, due to insufficient supplies of agricultural products to urban areas, the planners tended to control the surplus labor in

agriculture to move out of rural areas. In addition, urban China was struggling to provide enough jobs for returning school graduates from rural areas and the urban unemployed in cities. For such reasons, rural to urban migration was strictly controlled.

To prevent the rural population from working in the cities, the government limited the recruitment of workers from rural areas. Moreover, local governments tended to expel the employees from rural areas who were hired by urban employers. Other complementary policies were also implemented. For instance, the domicile control and

food distribution in urban areas based on hukou were enforced. Those policies are reflected in the Notice to Strict Control Rural Labor to Work in Urban Areas, issued by the State Council in 1981.

To ease the pressure of labor mobility coming out of rural areas, the Chinese government encouraged the development of rural industry with an aim to provide local off-farm employment opportunities for rural laborers. The so called labor policy of “leaving the land without leaving the villages” stimulated the development of TVEs by providing significant labor resources, which also led to a unique path toward industrializing rural China.

Permission to Migrate: 1984-1988

By the middle of 1980s, the HRS had already been extended to all of rural China, which symbolized the

completion of the first stage of rural reform. In addition, some other reforms of the rural economic system, like the abolishment of the People’s Commune System and development of TVEs, have encouraged labor mobility. Thanks to successful reform in rural areas, China began reforming the urban economic development. The main areas of

reform include empowering decision making within SOEs, increasing employment flexibility of enterprises, and encouraging development of non- SOEs in urban areas. Those reforms effectively promote the economic growth in urban areas and increase the demand for rural surplus labor.

The economic growth in non-agricultural sectors led to the growth of employment demand in the 1990s. To meet the labor demand from TVEs in coastal areas and construction in urban areas, it became necessary to allow labor mobility between rural and urban areas and across regions. As a result, the Chinese government started encouraging labor mobility in rural areas and implemented a set of new policies. For example, rural migrants who work or are self-employed in towns may register their hukou in towns under the condition of taking care of their

own grain rations. The government started allowing farmers to sell some agricultural products and to have their own business.

With economic development, migration restrictions have been further relaxed over time. To encourage the integration of the rural and urban economic spheres, the service and transportation sectors were opened to farmers. In 1986, SOEs were permitted to hire rural migrants. 1 To reduce rural poverty, the Chinese government formulated policies facilitating rural labor transfer from the central and western regions. Those active migration policies resulted in fast-growing migration flows in that period.

Slow down the Unbridled Flow: 1989-1991

However, the trend of migration policy was interrupted at times by macroeconomic fluctuations. When urban economic growth slows down, policy makers tend to protect the employment opportunities for urban residents by restricting the flow of rural migration. The economic recession from 1989 to 1991 was one such case.

In 1988 serious inflation caused by the overheated economy triggered macroeconomic adjustments in China. During a three-year adjustment period, the central government required the compression of investment in capital construction and tightened fiscal and monetary policies. Numerous construction projects were abandoned or stopped. China suffered from its lowest economic growth rates since 1978.

Under such circumstances, the urban labor market took a turn for the worse. To protect the employment opportunities for urban residents, numerous migrant workers were fired and local governments were required to strictly control labor coming out of rural areas. The restrictive policy is evidenced by Emergency Notices on Strict Control of Farmers Moving out of Rural Areas issued by the State Council in 1989. The first time, the rural migration

flow was defined as unbridled flow or blind flow (mangliu). As a result, many city governments began to charge migrants, arguing that migrants should compensate the costs of city development(Fan, 2009).

To ease the employment pressure in urban areas, the urban employers were required to fire rural migrant workers and send them back to rural areas. The government re-emphasized the method of“leaving the land without leaving the village” for rural labor transfer and encouraged local government to provide employment opportunities for rural surplus labor locally. However, the deteriorating macroeconomic situation formed a shock for TVEs.TVE employment began to decline.

Due to the strict control over rural migration, the total size of migration shrank during this period. In 1989 the number of migrants who lived in cities was significantly less than that in 1988.

Guiding the Migration Flow: 1992-2000

With increasing income disparities across regions and between rural and urban areas, migration became inevitable. Policy makers started to realize that it was impossible to simply block the migration flow through policies. Policy improved during this period with the normalization of migration.

The first practice was to establish 50 experimental counties developing rural human resources from 1991 to 1994; the pilot project was then extended to 8 provinces from 1994 to 1996. Meanwhile, the government began emphasizing the strengthening of the administration of rural to urban migration.

However, the measures to strengthen management were to issue various credentials. Before migration, rural farmers must procure a Migration Work Registration Card at the local governments of their hukou locality. At the destination places, migrants have to get an Employment License based on the card issued by the government of origin. By holding both the Card and the License, migrants were available to get relevant employment services from a government agency. Migrants who live in destination places more than one month need to apply for temporary living certificates in order to facilitate the hukou requirements.

Meanwhile, reform of the hukou system has been piloted in various regions. Migrant workers who work and live in small towns were allowed to own their non-agricultural hukou. According to a regulation issued by the central government in 1998, migrants who have legal housing, stable employment or living sources, and living more than

one year at a destination place were allowed to move their hukou registration to that place. However, the enforcement of the regulation varies across cities. In particular, big cities where local residents are subsidized by local finance are reluctant to accept newcomers, so the pace of reform in big cities is very limited.

In addition, the Chinese government has placed high value on the training programs for rural laborers and on employment services. For example, in 2001 the Ministry of Labor and Social Securities issued a document, Notice on Improving the Employment of Rural Labor Forces, establishing the Labor Reservation System. The Ministry also emphasized improving the skills of migrants and to set up a labor market information system, which was the first time the Ministry promoted the transfer of rural labor.

Despite attitude changes in government documents, the treatment of migrants was still subject to the political economy rooted in the interests of urban residents. Since the late 1990s, a large number of urban workers have been laid off by their employers and, as a result, the urban unemployment rate climbed for a few years accompanying a declining labor force participation rate (Cai, et al., 2005). The urban labor market dislocation was translated to

migrant workers. To provide job vacancies for the urban unemployed, many cities adopted employment protection for local workers. Despite discrimination in terms of wage and working conditions, migrants were excluded from some

employment opportunities (Cai, et al., 2001).

Treating Rural Migrants Well

Since 2000, relevant central government documents began to highlight active support and encouragement for rural migration, clearly proposed reform of the institutional segmentation between city and country, and eliminating the guiding ideas that unreasonably restrict rural residents migrating to the city for work. This implies that China has started integrating urban-rural employment policy.

In analyzing the details, it is clear that the evolution of migration policies consists of the following aspects. One of the positive changes was to remove fees imposed on migrants, including temporary living fees, administration fees for migrants, and service fees for migrant workers. In addition, the Chinese government started addressing the issue of training the migrant workers. In 2003, the State Council issued Training Plans for Migrant Workers: 2003-2010, which proposed that central and local governments should finance the training programs for migrant workers.

The nature of this policy is unambiguous and stable and was clearly written into the 10th and 11th Five- Year Plans published in 2001 and 2006 respectively.By approaching the flow of labor with encouragement, and more importantly by creating fair conditions to improve the migrant employment, accommodation, children’s education, and social security, these policies have gradually become enforceable and effective measures.

In 2006, Document No. 5 of the State Council entitled “State Council Suggestions on Solving Certain Issues Regarding Migrant Workers” enhanced the encouragement, guidance and help regarding the flow of rural labor, to the level of“conforming to the objectives of industrialization and urbanization,” focused attention on solving major

problems in the interests of the rural migrant workers, and proposed the principle of “fair and nondiscriminatory

treatment.”

Passage of the Labor Contract Law in 2007 indicates the great importance the government attaches to protection of the rights and interests of ordinary workers, including the migrant workers, and a point at which policy orientation altered tremendously. The same year the Employment Promotion Act directly targeted barriers to employment faced by rural migrant workers in providing that “rural laborers going to work in the city enjoy equal labor rights with urban workers; setting discriminatory restrictions on rural workers going to work in the city is prohibited.”

In addition, in 2008 the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security announced that measures addressing transferable pension for migrant workers would be taken by the end of 2008 (Yin, 2008). According to the announcement, migrant workers will have two options in terms of participation in the pension system. For those who

have stable jobs in the urban labor market, will be allowed to join the urban pension system. As a complementary program, for migrant workers with high mobility, a portable individual account will be designed and their accounts will be connected to the current urban system if the migrant worker chooses so.

These policy changes are positive responses of the Chinese government to realistic institutional demands, and thus conform to the requirements of changes in the stage of economic development. They may therefore eventually find expression in genuine improvements in the conditions of migrant workers. A rough picture is that prior to 2003, the basic wage levels of migrant workers’ saw no changes in recent decades, but with the emergence

of labor shortages, they increased by 2.8% in 2004, 6.5% in 2005, and 11.5% in 2006 (outstripping the growth rate of the economy). At the same time, due to the intervention of and role played by policy, migrant workers’ wage arrears have decreased significantly, and their working and living conditions improved.

In the new century, local governments have made greater efforts in reforming the hukou system. In recent years, one common practice in this reform area is to attempt to establish a unified hukou regime integrating rural and urban population registration, by abolishing the distinction between agricultural and non-agricultural hukou identities and integrating them into a unified residential hukou. By 2007, there were 12 provinces that had carried out reforms of this kind. In addition, many cities further loosened criteria of applying for local registration for family reunion, the elderly joining adult children, youth joining parents, investors, the talented, and local housing buyers.

Such reform, however, has encountered some difficulties. One notable challenge facing local governments is that the nature of hukou is not simply a population registration system, but welfare benefits contained in it. An attraction of urban hukou is its entitlement of access to social security and other public services; the provision of this is affiliated with local hukou status and differentiated between rural and urban areas. Even if a city announces a unified population registration system, or loosens criteria for migrants to apply for local hukou, if its fiscal capability is constrained to provide universal public services to all residents regardless of their origins – that is, both previous urban and rural residents can get access to equal social welfare and public services – such a change in method of population registration is meaningless. In reality, reforms of this kind in cities that announced unified hukou registration but failed to issue related entitlements because of fiscal constraints have actually been relaxed.

IV. Contributions of Migration to Economic Development and Poverty Reduction

Not only does migration reflect economic transition and liberalization but indicates labor market development and changing rural-urban relationship. First, rural labor transferring from economic sectors with low to high marginal labor productivity has fostered economic growth through improving economic efficiency. Second, the labor market

participants have been better off through migration, which is an important means to poverty reduction.

4.1 Source to drive economic development

At the early stage of economic reforms, China was a developing country with typical dual economic structure, notwithstanding the rich human resources she owned. In the light of the endowment, China had to face with scarcity of capital and unlimited labor supply. To escape from the dual economy, China needs to take advantage of the rich human resources to avoid the constraints with scarce capital. Exploiting the advantage in human resources through increasing employment is the road China must get through during economic development.

In fact, the Chinese economic practices in the past three decades have followed the above path. It is the increasing employment that keeps providing sources to foster economic growth. In particular, through rural to urban migration, the Chinese manufacturing has taken advantage of low labor costs, which makes the labor intensive industries competitive. It is estimated that the unit labor cost in Chinese manufacturing was about USD 1.13 per

hour in 2008, 5-8% that of developed economies.

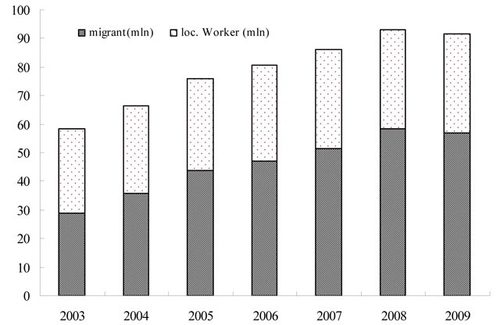

Since mid-1990s, the employment of SOEs in manufacturing has been decreasing after SOE restructuring. In contrast, more and more migrant workers have joined this sector at the same period. According to the rural household survey conducted by NBS, 39.1 percent migrant workers worked in manufacturing in 2009 while the share was only 25.2 percent in 2003. As Figure 2 displays, the employment in manufacturing totaled 91.74 million in 2009, and 62 percent of them were migrant workers, 13 percentage point growth of the share since 2003.

Figure 2 The composition of employment in manufacturing: migrant workers and local workers Source: Du Yang (2010).

Similarly, rural migrants have played more and more active role in other off-farm sectors. According to NBS rural household survey, in 2009 there were 37 million migrant workers employed in tertiary sector, which accounted for 25.5 percent of total migrant workers. Migrant workers turn out to be the indispensable component of urban employment.

With dual economic structure, the transferred labor forces would enhance their marginal productivity whether working in manufacturing or service. Therefore, labor reallocation from low to high productivity sector results in improvement in economic efficiency, which contributes to overall economic growth. Previous studies have demonstrated that labor mobility between rural and urban areas had contributed 16%-20% to overall economic growth during the first two decades of reforming period (Cai and Wang, 1999; the World Bank, 1998).

In the new century, the size of rural to urban migration has been increasing, which accounts for a large share of urban employment. Through sufficient migration, the marginal productivity of labor in agriculture has been close to that in non-agricultural sectors. Therefore, the effects of migration to growth could be more significant due to larger size of migration but shrinking due to the diminished gap between agriculture and non-agricultural sectors.

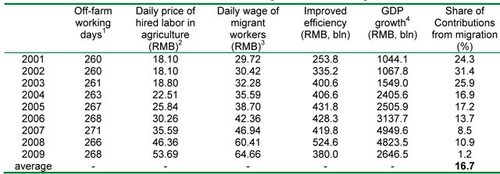

There is no study estimating the contribution of labor migration to economic growth in the past decade. By calculating the productivity gap between agriculture and non-agricultural sectors, we may roughly estimate the contribution of rural labor migration to overall economic growth.

Taking advantage of National Agricultural Product Cost-Revenue Data, we may get the information of hired labor price. We assume that the price of hired labor reflects the marginal productivity of labor in agriculture while the price is the mean of prices of hired labor for three main agricultural products, rice, corn, and wheat. The other assumption is that in urban labor market the marginal productivity of migrant worker equals to wage rate. It is expected that the marginal productivity in agriculture and nonagricultural sectors will converge when passing through Lewis turning point. For instance, the price of hired labor in agriculture is 61% of migrants’wage in 2001, and the ratio increased to 85% in 2009, which implies that the efficiency improvement through labor mobility starts shrinking even though the size of labor migration is increasing.

Combining various sources of information together, it is possible to estimate the share of contributions to overall economic growth from rural labor mobility. The second and third columns in Table 3 give the productivity improvement for each worker moving from agriculture to non-agricultural sector. Multiplied by average days in off-farm sector for each migrant worker and the total number of migrant workers, we can get the total efficiency improvement through labor migration, as displayed at the fourth column of Table 3. The last column is the annual shares of contribution to overall economic growth from labor mobility.

Table 3 the contributions of migration to economic growth

Source: (1)“1” from Wu and Zhang (2010);

(2)“2” from Wang (2010);

(3)“3” Calculated from “1” and Du (2010);

(4)“4” from China Statistical Yearbook 2010, China Statistical Press.

With coming Lewis turning point, the contribution of labor migration to overall economic growth declines, even though it is still an important source for driving growth. From 2001 to 2009, the average share of contribution to overall economic growth is 16.7%. However, the trend indicates a declining share since 2003, the year that is believed as a turning point (Zhang, et. al, 2010).

4.2 Reducing the regional inequality and disparities between urban and rural areas

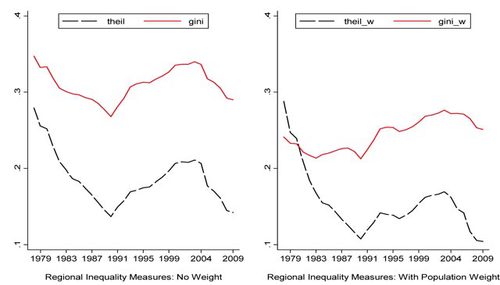

Labor mobility across regions has been increasing with growing labor migration. Most migrants are responsive to price signal from labor market, therefore, the move from the regions with low to high labor productivity is helpful to reduce the regional disparities. Furthermore, the bigger the size of migration flow, the more significant the effect to reduce regional disparities. Regional aggregated data imply that labor mobility across regions could

play a dominant role in reducing regional disparities. Regional inequality indices are depicted in Figure 3. In 1980s, economic reform was focused to encourage micro economic units in both rural and urban areas as well. The improvement of technical efficiency had comprehensive effect of growth across regions, which led to declining regional inequality. As shown in the figure, the Gini coefficient of provincial GDP decreased from 0.347 in 1978 to 0.268 in 1990. When weighted by provincial population, the two numbers are 0.241 and 0.2132 respectively. Considering that the size of labor migration in 1990s was still limited, labor mobility was not a dominant factor affecting inequality at that time although it contributed to reducing regional inequality.

The Chinese economy recovered from a depression in 1992, but since then the improvement of allocative efficiency has played dominant role in economic development. The regional disparities had increased again because of the difference of specialization across regions. The Gini coefficient of provincial GDP peaked at 0.34 in 2003.

Figure 3 Regional Disparities of Economic Growth in China: 1978-2009

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China Statistical Yearbook (various years), China Statistical Press.

With passing through Lewis turning point, the situation of rural to urban migration has developed significantly, as evidenced by frequent shortage for and growing wages of unskilled workers. Meanwhile, labor intensive industries started to transfer to Central and Western China. These factors combining together led to reduce the regional inequality. As figure 3 presents, the regional inequality indices have been declining since the peak in 2003. Although there are other factors contributing to regional disparities, the consistency between turning point of regional disparities and Lewis turning point still implies the active role of labor mobility in reducing regional inequality.

Rural to urban migration affects the income inequality between urban and rural residents too. The income gap between urban and rural areas is supposed to be the most important source of income inequality in dual economy. Accordingly, in addition to public policy, rural to urban migration is the basic means to reduce regional inequality too.

Although the rural-urban income gap is clear, the existing statistical system does not include migrant workers sufficiently, which may cause serious sampling bias and overestimate income inequality (Park, 2007). In this case, the active role of rural to urban migration in reducing inequality is hard to measure.

Unfortunately, it is not easy to get national representative time series data including migrants. Here, the 1% population sampling data is employed to test the potential changes of inequality when migrants are included. The first column of Table 4 is estimation that migrants are excluded while the second column is the case including migrants. The results in this table indicate that all the inequality indices would decline when migrant workers are

included in the sample.

Table 4 Overall inequality changes with unbiased sample

Source: author’s calculation from 1% sampling survey.

It is expected that labor migration will play even a more significant role in reducing inequality between rural and urban areas when the size of migration increases and the wage for unskilled workers grows. For instance, the migrant workers totaled 114 million in 2003 and their average monthly earnings were RMB 703 at price in 2001. In 2009 the total number of migrant workers increased 27.6%, and their average monthly earnings increased 74% in real terms.

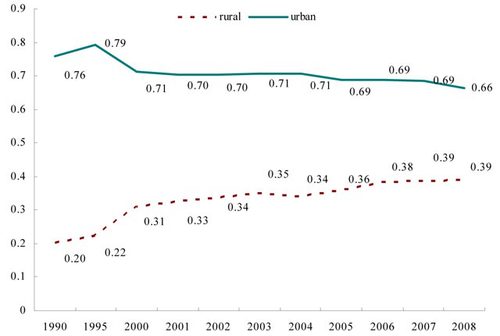

4.3 The role in poverty reduction

As figure 4 displays, for either rural or urban areas, the labor market income is the most important income generator for households. In 2008, labor market earnings accounted for 2/3 urban and 40% rural household income. Considering that farm income also depends on labor input in agriculture, the share of labor income in total income of rural households should actually be higher. The rural households have been more relying on wage incomes over time while this trend is not in urban households. Wage income accounted for 20% of total income in 1990 while the share doubled in 2008.

Figure 4 Share of labor income in household incomes, 1990-2008

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China Statistical Yearbook (various years), China Statistical Press.

Figure 5 explains the role of wage income on income growth of rural households. The horizontal axis is the share of wage income in total income and the vertical axis is per capita net income of rural household. Each dot in the figure represents a province. A simple regression indicates that the rural households in provinces with high share of wage income tend to be richer. The goodness to fit is 0.49. This figure implies that the rural households

in coastal areas where the off-farm employment opportunities are plenty are more possible to use labor market and more rely on off-farm incomes. If we expected that the Central and Western China would follow a similar pattern that has already been applied in coastal areas, the share of wage income in total incomes would keep increasing in the future in those less developed regions. For instance, Guangdong, the province with highest share in 2008 was 57.6% while the lowest one is Xinjiang, only 12%. This variation across regions indicates that there are potentials in less developed regions to catch up through using labor market.

Figure 5 Per Capita Rural Household Incomes and Share of Wage Income by Province in 2008

Source: China Statistics Yearbook 2009, China Statistical Press.

As for the poor households in rural areas, limited by economic endowment they owned, they are incapable of getting access to other economic opportunities. In this case, human resources are the most important endowment the poor households have. Once the labor market barriers are reduced, the poor households may reduce poverty by

reallocating their labor into off-farm labor market through migration.

Regarding to the formation and implementation of poverty alleviation policies, the poor households may use labor market to reduce poverty automatically, which lowers the costs of policy implementation. To encourage labor mobility, increasing human capital accumulation is the most essential way. More importantly, the investments in

people are not only the sole way to poverty reduction but the goal of development per se.

The empirical study (Du, et. al., 2005) demonstrates that, thanks to fast economic growth and labor market development, labor migration from central and western China has kept growing since the late 1990s. The likelihood that low-endowment households choose to migrant will be on increase over time. By contrast, the importance of local

geography in the migration decision has declined. Households near the poverty line are more likely to have a migrant than richer or poorer households. Hence, for some households, migration plays an important role in escaping poverty. Urban policy, e.g., hukou restrictions, is not perceived to have erected significant barriers to migration by poor

households if rural people do not seek permanent residence there. Importantly, migration increases household income per capita by between 8.5 and 13.1 percent and migrant remittances are both significant and responsive to the needs of household members.

V. Labor Migration and the Challenges of Poverty Reduction

One aspect we need to bear in mind is that not all poor households are capable of using labor market to reduce poverty although labor migration has been seen as an effective way to poverty reduction in general. When passing through the Lewis turning point, most surplus laborers in rural areas have already migrated. It is necessary to find an additional policy tool to help the remaining poor out of poverty. Meanwhile, migrants in urban areas could fall into poverty too given the fact that they are not effectively protected by the urban social protection system. To a large extent, this challenges current poverty reduction system.

5.1 The limitations of using labor market to reduce poverty

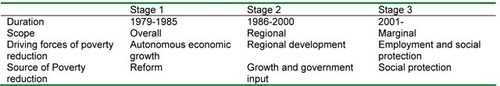

The analysis in above section indicates that the probability to fall into (rural) poverty would be significantly reduced once the rural household members migrate. However, people who did not migrate tend to be more homogenous than before and consist of the elderly and less educated people who are not able to use the labor market (Du and Wang, 2010). This change in labor market makes the nature of rural poverty transform, which could be a factor to characterize various phases of poverty reduction, as summed up in Table 5.

The first phase dates back to the period 1978 to 1985 when the rural reform indicated by the adoption of household responsibility system. During this short period of time, the numbers of rural residents living under the absolute poverty line were halved, the most significant achievement in human history. The poverty reduction at this phase can be viewed as the effect of successful economic reform in rural China, because the reform released

hundreds of thousand farmers from the shackle of People’s Commune System and increased the productivity of agriculture by improving incentives.

At the second stage, the regional features of poverty appeared. Constrained by natural conditions and other factors, some regions were sluggish in economic growth and could not achieve economic development automatically. The Chinese government expected to drive the economic growth in poor areas through special poverty alleviation policy. When the poor benefited from regional economic growth, the special program would have effect on poverty reduction.

At this stage, China still relied on economic growth to reduce rural poverty, but the regional economic growth was mainly driven by government, rather than the autonomous growth at the first stage. The regional economic growth did help some poor who lived in the remote areas and are short of economic opportunities to move out of poverty.

After the first two stages, those who could make use of economic growth were not poor anymore. Therefore, the government efforts to poverty alleviation should be focused on the remaining marginalized poverty. The corresponding policy instruments should be adjusted too, i.e., transforming from creating opportunities to direct

assistance.

Table 5 Changing Features of Rural Poverty

Source: cite from Du and Cai (2005)

Based on the effect of growth on poverty reduction and composition of poor population, we may understand the changing characteristics of rural poverty at current stages.

The first observation is the insignificant effect of projects and general economic growth on poverty reduction. The government’s efforts to poverty reduction were mainly implemented through projects. The effectiveness of those programs is based on two assumptions: (1) the projects being implemented in rural areas can facilitate regional economic growth, and (2) regional economic growth can lift the rural poor out of poverty. However, those two assumptions are no longer the truth after the second phase of the poverty reduction ended. According to existing studies, due to implausible directions of investments of poverty alleviation funds, the effects of projects on economic

growth are very limited (Cai, et. al, 2000). Another study by the World Bank (Ravallion and Chen, 2004) shows that during the 1990s, the overall economic growth increased the income gaps and only people with two highest income deciles have faster income growth rate than average. In 2001 and 2002 annual PAF input were 3.7 times and 2 times of that during the periods of Eighth Five-Year Plan and Ninth Five Plan respectively, while the effects on reduction of

poverty incidence were only half and one third of corresponding periods.

A second observation is that the regional poverty alleviation programs have limited coverage of the rural poor. Under the regional development-oriented programs of poverty alleviation, county is the basic unit of targeted area. The central government arranges all PAF to support the development of poor counties. The selection of poor counties directly affects the accuracy of the PAF’s target and thus the effectiveness of the programs. The study (Park et al.

2002) shows that some non-economic determinants make the selections unreasonable. In 2000, only 60 percent of rural poor population lived within the 592 State Designated Poor Counties (SDPC). To avoid the inaccuracy in poverty targeting caused by the nature of countywide investment of the funds, in 2001 the Chinese government began to emphasize targeting poor villages or even poor households and 148 thousand poor villages were selected to target 83 percent of total poor population in rural areas (Rural Survey Organization of National Bureau of Statistics, 2004). Now that the county governments allocate the distribution of PAF, it is believed that the poverty alleviation funds are more likely to be invested countywide rather than targeting the lower levels and therefore the programs cover the poor poorly.

In addition to the observed features of county-based strategy of poverty alleviation, the composition of the rural poor has been changed as well. Among the remaining poor, there are about one fifth, who are Five Guarantees Families3, more than one third are the disabled, and over one fourth are those who live in the areas with extremely adverse natural resources. In short, those people in fact lack ability to take advantage of the projects aiming at regional poverty reduction and thus are unlikely to benefit from an overall economic growth. According to official statistics (Rural Survey Team of National Bureau of Statistics, 2000), the human capital endowments of rural poor families are significantly lower than non-poor families. For instance, 31.3 percent of poor families had no single family member with the education attainment above primary schooling. Adult illiteracy rate among the poor was 22.1 percent, while that of non-poor families was only 8.9 percent. In addition, some other characteristics of poor families made it difficult for them to move out of poverty. Poor families turn out to have bigger household size with high dependency ratio and own family asset with low quality, which produces vulnerability when they face risks. In order to

cope with this kind of poverty, the general strategy of poverty alleviation should shift to one with more precise targeting through social protection programs in rural areas.

The different judgments on the nature of rural poverty in China imply different policy implications. If the rural

poverty has already been dominated by marginalized poverty, the poverty alleviation strategy should be focused on targeting individuals and households directly. In this regard, rural dibao system should play a more active role in poverty reduction.

At the new stage of anti-poverty efforts, the rural dibao system has been widely expanded in rural China, which parallels the rural poverty alleviation system. By the end of 2009, there were 22.92 million rural households; 47.6 million individuals who were covered by the rural dibao system. In 2009 the average of rural dibao lines all over China is RMB 100.8 per month and the average per capita benefit is RMB 68 per month. Integrating rural dibao system and poverty alleviation system is under discussion.

5.2 Migration of poverty and the integration of poverty reduction system

As noted earlier, rural to urban migration has played active role in reducing rural poverty. However, with increasing size of rural to urban migration, their situations in urban areas are of big concern. Most migrants working in urban informal sectors are suffering from more vulnerability than the urban residents. The increasing size of migration has been challenging the segmented social protection system between rural and urban areas.

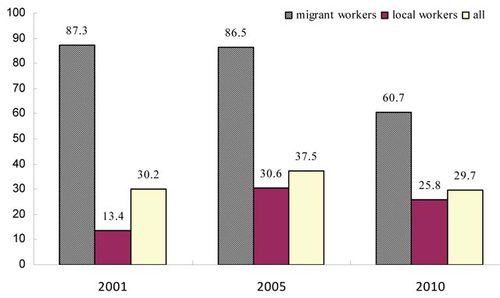

Differing from absolute poverty in rural areas, the poverty of rural migrants is reflected in various ways, mostly from the risks and uncertainties due to the urban labor market fluctuations. Compared to local workers, migrants work more informally in urban labor market, which leads to high risks. According to China Urban Labor Survey conducted by Institute of Population and Labor Economics, the share of migrants working in the informal sector is much higher than the local workers, as displayed in figure 6. In 2010, 60.7% of migrants worked in the informal sector while the number for local workers was only 25.8%.

Figure 6 Informality of Migrant and Local Workers

Source: authors’ calculation from CULS.

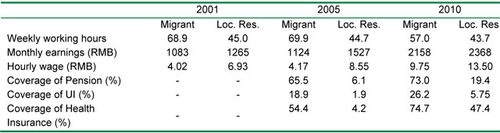

The informal sector in China is characterized as low income, high labor intensity, low coverage of social protection, and high rate of job turnover, which result in vulnerability and poverty. Based on micro level data, it is easy to find gaps between migrant workers and urban workers in terms of main labor market outcomes and social protection coverage, as presented in Table 6. The difference in monthly earnings is insignificant, so does the poverty

incidences measured by income. However, due to the disparities of social protection, in order to maintain the income level local workers achieved, migrant workers have to put in additional efforts. For instance, in 2010, average weekly working hours of migrant workers were 30.4% higher than local workers. Therefore, local workers’hourly earnings are 38.5% higher than migrant workers.

Table 6 Vulnerability of Migrant Workers in Urban Labor Market

Source: authors’ calculation from CULS.

Migrant workers would pay additional prices in health, which would then translate to poverty notwithstanding the insignificant difference in poverty incidences measured by income. According to existing empirical study (Du et al., 2006), an additional hour increase in monthly working hours would worsen migrant workers’ self-reported health

status 0.02 percentage point. In other words, if migrant workers try to keep equivalent health status to local workers and ease their work intensity to the level of local workers, their poverty incidence measured by income will increase by 15-35%.

5.3 Integrating the social protection system

Rural to urban labor migration connects the rural and urban poverty together while the two phenomena were separated before. In this case, accompanying migration, poverty could be transferred from rural to urban areas too. In fact, in other economies, it is quite often to see migration poverty, which is called urbanization of poverty (Psacharopoulos et al., 1995). Urbanization is one of the most important goals for most developing countries but not urbanization of poverty. Prior to the reform, due to the segmentation between rural and urban areas, poverty could not

move to urban areas naturally. Even at the early stage of reform period, because the size of migration was very limited, the migrated poverty was not obvious too. In addition, rural people who own relatively high level of human capital tend to respond to the labor market signs first and their performance in urban labor market is good, which

let them have low probability falling into poverty in cities.

When the labor mobility is insignificant, the distribution of poverty would be more likely to be regional. If this is the case, targeting the poor areas rather than individuals/households will be relatively more efficient. The Chinese experiences in the past decades have already proved that.

In recent years, with increasing size of rural to urban migration, the composition of migrants has been more and more diversified, including not only labor forces but dependent population. Chan (2003) finds that the rural to urban migration accounted for 60% of urbanization. Under this context, there are needs to understand the composition, level, and features of urban poverty and to reform the urban poverty alleviation system by including migrants.

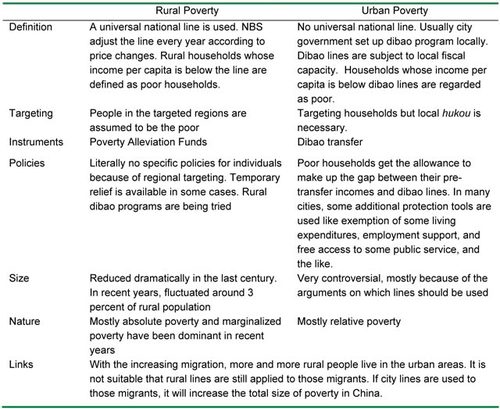

In contrast to the changing situation of urban poverty, the reforms on urban poverty alleviation system is not sufficient. In particular, when facing the increasing connection between rural and urban poverty, the poverty reduction system has not been adjusted accordingly. As a result, policy instruments targeting both poor rural areas and urban poor with local hukou could not reach the poor migrants. More importantly, the migrating poverty is mostly rooted

from the vulnerability originated from insufficient social protection, so anti-poverty policies trying to reduce income poverty may not have effect on alleviating migrants’ multi-dimensional poverty. Table 7 summarizes the definition, targeting, policy instruments, and the areas to be reformed for both urban and rural poverty reduction system as well.

Table 7 Rural and Urban Poverty: Connection and Segmentation

In the light of the migrating poverty originating from social protection disparities, the integration of urban and rural social protection system will be helpful to avoid the moving poverty. Similar to many other countries, the social protection system in China is composed of both social security system and social assistance. There exist obvious gaps between urban and rural areas in terms of these two basic pillars. It is believed that current social protection

system is hard to fit in with the needs of increasing migration. Figure 7 displays the main framework of current social protection system in China. It is easy to find significant institutional segmentation in the two pillars. In particular, the two parallel systems in rural and urban areas can easily ignore rural to urban migrants. For instance, the major social protection instruments including dibao, health care, and pension system are suffering from how to integrate the rural and urban systems. The institutional disparities explain the gaps of coverage that we see in Table 6.

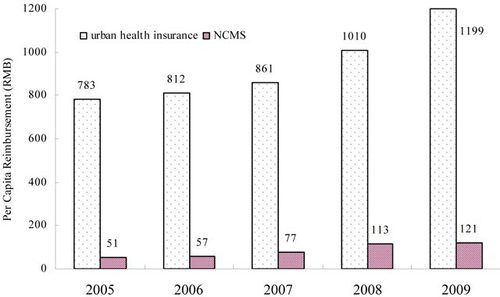

In addition to coverage, the benefits the beneficiaries accrued from the social insurance system vary across migrants, rural residents, and urban residents. For example, most rural residents have been covered by New Cooperative Medical System. However, the average reimbursement from NCMS is much less than the benefit urban residents get from urban health insurance. In 2009, average per capita reimbursement for rural residents was RMB 121 while the number was RMB 1199 for urban residents, see Figure 8.

Figure 8 the gap of benefit from health care insurance

Source: Du Yang (2010)

In China, integrating urban and rural development has been identified as one of the key components of Scientific Development. In this context, the social protection system including poverty reduction has been facing with challenges and opportunities. In order to reduce the vulnerability migrant workers faced in urban labor market, integrating social protection system between rural and urban areas is a necessary condition, which not only needs the integration of institutional framework but reduces the benefit gaps.

VI. The Relevance to Other Developing Countries

Thanks to fast economic development in the past three decades, the turning point in the Chinese labor market declares the end of the era with unlimited labor supply. However, the contemporary China is still with the features of a developing economy and Chinese practices in poverty reduction by using labor market are of relevance to many other developing economies.

6.1 Experiences in rural labor migration

After the review on procedure, policy evolution, and the impact on economic development and poverty reduction of migration, it is easy to understand that the general trend of rural labor migration has been consistent with the liberalization of the Chinese economy despite of some policy changes back and forth during the process. In general, the Chinese experiences in rural labor migration have been reflected by the following aspects.

The first one is to empower farmers the freedom of employment choices. With the introduction of Household Responsibility System in rural areas in early 1980s, the rural households obtained property rights and became de facto operational units in agriculture. Since then, the rural households have been able to allocate their working time and choose the economic activities freely. The right of employment choices and labor allocation is the premise to rural labor migration institutionally.

Second, China gives scope to the market mechanism playing dominant role in labor migration. In the past two decades, the TVEs have absorbed more than 100 million rural labor forces and the other 100 million rural labor forces migrated across regions. This mobility is not manipulated by the government but the natural response to labor

market signals. The Chinese experiences demonstrate that the developing countries have to rely on the market mechanism to increase off-farm employment.

Thirdly, the Chinese government gives sufficient respect to farmers’choices. It is this respect that guarantees the smooth transformation of rural surplus labor. Following the gradualism during reforms, by relaxing policies and pushing institutional changes, the Chinese government takes the initiative in helping off-farm employment. The

process follows the objective of the law of economic development.

Finally, the Chinese government values the investments in human resources. The migration per se is the procedure of human investments, but the government still needs to be dedicated to human capital investments in order to promote the transformation from farmers to industrial workers. By keeping investment in human capital, the

average years of schooling in rural population have been increasing in the past three decades, a period of fast economic growth in China, which laid the foundation to develop non-agricultural sectors. In addition to formal education that is valued by both the government and rural households, the Chinese government has initiated various training programs to facilitate labor migration in recent years. In particular, training the labor forces in poor areas has

been included in the special poverty alleviation schemes.

However, when passing through the Lewis turning point, the growth of labor costs is sped up. Even in labor intensive industries, the trend of substitution of labor with capital has been more and more obvious. With capital intensity, the demand for skilled workers has been increasing. If migrant workers’skills cannot meet the demand for industrial upgrade, China will have to face the challenges when transforming its economic growth pattern. In this

regard, China needs to keep investments in human capital and improve the efficiency of the investments.

6.2 The diversities and similarities with other developing countries

The general development path

Although China has become the second largest economy in aggregate terms, the level of per capita GDP at a low level in the world indicates that China is still a developing country. The similarities between the Chinese economy and other developing countries imply that the past development path China has taken and the success

in poverty reduction would be meaningful to other developing economies as well.

First, China has similar endowment structures with many other developing countries. As far as the population structure is concerned, most developing countries do not complete demographic transition before economic take-off, which means that they are at the phase with high fertility, high mortality, and high natural growth rate of total population. Once the economic development path does not comply with those constraints correctly, the developing countries are more prone to fall into the poverty trap.

Typically, a developing economy is featured by dual economic structure before take-off. In such a context, the development has to be facing with the scarcity of capital and surplus labor. If the developing countries deviate from the development path conforming to their advantages and develop capital intensive industries, it will be hard for them to gain sustainable economic growth. On the contrary, by developing labor intensive industries and expanding non-agricultural sectors, the economy could take off by generating sufficient employment and breaking through the dual economic structure. The latter development path has been proved by the Chinese practices in the past three decades.

Of course, the development of labor intensive industries in China is determined by China’s endowment structure. The other countries have their own conditions and the China’s way is not the only choice. For example, the population size China has been sufficient to form domestic market for manufactured products while this condition may not exist in other countries. However, there are some sub-sectors in tertiary industry. The other developing countries can choose their own industrial policies as per their own endowment structure.

Second, as for using labor market to reduce poverty, the effect could be significant at the early stage of economic development. In a country choosing to develop capital intensive industries, the distribution of national income is biased to capital owners in general. As a result, it increases the inequality between the poor and capital owners. In contrast, following comparative advantages, the developing countries could increase employment through the development of labor intensive industries. In turn, the poor may get a chance to increase their earnings and reduce poverty.

Third, like many other developing countries, China was constrained by insufficient development of market mechanisms at the early stage of economic development. In particular, there existed institutional barriers in the labor market. Given the complexity of labor market institutions, the details of labor market regulations vary across countries. But it is quite common in developing countries that labor mobility is blocked by various obstacles. As noted earlier, free labor mobility is one of the best ways to improve the economic efficiency in a dual economy. If this is the case, eliminating the institutional barriers in the labor market will be a necessary condition to facilitate labor mobility and poverty reduction.

The uniqueness of China’s development path

The economic transitioning in China differs from many other developing countries. For example, to facilitate the transfer of surplus labor in agriculture, China had achieved rural industrialization through the development of TVEs, so called “leaving land without leaving hometown”. At the early stages of economic development, China was not a complete market economy. Despite of the pressing situation to transfer surplus labor, the significant segmentation between urban and rural areas blocked the migration flow. In this case, the rural industrialization was the only choice to facilitate the transfer of agricultural surplus labor. However, it is still an open question of whether rural industrialization could be a universal model applied to other developing countries. Due to the following

considerations, the other countries should be cautious when using the strategy.

First, with economic development and transition, the overall pattern of rural labor transfer has shifted from “leaving land without leaving hometown” to migration to urban areas. All in all, the rural industrialization could not achieve the efficiency from scale economy and industrial agglomeration that urbanization does. As a result, the employment demand moved from rural areas to the cities. It is thus clear that the Chinese practice in fact follows

the general law of economic development.

Second, even in China, the rural industrialization did not apply to all the regions. Even in the golden age of TVEs development in 1980s and 1990s, most poor regions are reluctant to transfer their agricultural surplus labor locally. There are some other factors determining rural industrialization, including the development of local markets, the level

of economic development, local institutions, etc.

Regarding the case in other developing countries, they have to be concerned about their specific conditions. In this regard, replicating China’s rural industrialization may not be a right choice. Both for TVEs development and the latter migration across regions, each pattern reflects the development of market mechanism and the correction of the

traditional distorted institutions. China needs to stick to the path of a market economy, so do other developing countries seeking development.

6.3 South-south leaning: experiences, lessons, and prospects

Despite fascinating economic performance and achievement in poverty reduction, China has accumulated some experiences and lessons on the methods of development. In the future, developing counties with similar initial conditions like China may learn from them to facilitate their own development.

First, a desired institutional environment is necessary for economic development and poverty reduction. Therefore, the governments in developing countries need to reduce the institutional distortions as much as possible. As noted above, the developing countries may be subject to incomplete markets. On the path to a market economy, the governments should devote their energy to eliminating institutional barriers in both product and factor markets.

Second, gradual reform is of importance to developing countries. It takes time for developing countries to construct and complete their market institutions. On the path to a mature market system,a stable socioeconomic environment is essential to develop. China’s practices have witnessed that gradual reform gives room to decision makers to correct their policy biases, which minimizes the costs of reforms.

Third, although using labor market is an effective tool to poverty reduction, in order to cover all the poor, a comprehensive poverty reduction strategy should include social protection system. China has witnessed the active role of using labor market in poverty reduction in the past three decades. However, with greater achievement of poverty reduction, labor migration has diminishing effect to reduce poverty, in particular the marginalized poverty. Therefore, overall poverty alleviation relies more and more on coverage of social protection.

Fourth, to break through the dual economy, the developing countries may devote to integrating the rural and urban economies. In the mean time, they should also avoid the notorious urban diseases during urbanization. Unfortunately, it is observed that unharmonious urban expansion has taken place in some developing countries. When urbanizing, for example, congestion, pollution, and disordered society have been on the rise. More

importantly, due to insufficient employment opportunities, the rural to urban migration also brings the movement of poverty, as evidenced by a forest of slums. In this case, urbanization does not increase the wellbeing of rural migrants effectively. To achieve the wellbeing improvement during urbanization, the following reforms are needed.

First of all, a desired land tenure system persistently influences the nature of labor migration. China started the reform and opening-up from rural reform, in particular the reform on rural land tenure system. The introduction of HRS three decades ago empowers each household the right to utilize the land, which encourages farmers’ agricultural production and, more importantly, provides the very fundamental produce for farmers’ livelihood. China

values egalitarian distribution of land among farmers when reforming its rural land tenure system, which guarantees the property rights of the poor. The Chinese practices have already demonstrated that perpetual, equal, and stable land rights enhance farmers’ reservation wage rates for off-farm labor supply. If this is the case, the rural residents’migration decisions would be Pareto improvement.

Secondly, in order to avoid migration of poverty in urban areas, developing countries have to devote to constructing comprehensive social protection network. In fact, China still has a long way to go to integrate the social protection between urban and rural areas. To achieve the goal, the coverage and benefits of social protection in rural areas have to be increased gradually.

References:

Cai, Fang (eds) (2006), Reports on China’s Population and Labor No.7: Demographic Transition and Its Social and Economic Consequences, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Cai, Fang (eds) (2007), Reports on China’s Population and Labor No.8: The Coming Lewisian Turning Point

and Its Policy Implications, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Cai, Fang and Dewen Wang (1999), “Sustainability of China’s Economic Growth and the Contribution of

Labor”, Economic Research Journal, No.10, pp.62-68.

Cai, Fang and Meiyan Wang (2007), “A Counterfactual Analysis on Endless Surplus Labor in Rural China”,

China Rural Economy, No.10, pp.4-12.

Cai, Fang, Yang Du and Fang Chen (2000), “Investment Guide on Western Development Strategy:

Implications from the Utility Efficiency of Aid-the-Poor Funds”, World Economy, No.11, pp.14-19.

Chan, Kam Wing and Ying Hu (2003), “Urbanization in China in the 1990s: New Definition, Different Series,and Revised Trends”, The China Review, Vol.3, No.2, pp.49-71.

Department of Rural Surveys, National Bureau of Statistics (2000), Poverty Monitoring Report of Rural China

2000, China Statistics Press.

Department of Rural Surveys, National Bureau of Statistics (2004), Poverty Monitoring Report of Rural China

2004, China Statistics Press.

Du, Yang (2010), “Migration of Rural Labor: Policy Options during Transition”, Comparative Economic & Social Systems, No.5, pp.90-97.

Du, Yang and Albert Park (2003), “Migration and Poverty Reduction---Evidence from Rural Household

Surveys, Population Science of China, No.4, pp.56-62.

Du, Yang and Fang Cai (2005), “The Transition of the Stages of Poverty Reduction in Rural China”, China

Rural Survey, No.5, pp.2-9.

Du, Yang and Meiyan Wang (2010), “New Estimate of Surplus Rural Labor Force and Its Implications”,

Journal of Guangzhou University (Social Science Edition), Vol.9, No.4, pp.17-24.

Du, Yang, Albert Park and Sangui Wang (2005), “Migration and Rural Poverty in China”, Journal of

Comparative Economics, Vol.33, No.4, pp.688-709.

Du, Yang, Robert Gregory and Xin Meng (2006), “The Impact of the Guest-worker System on Poverty and the

Well-being of Migrant Workers in Urban China”, in Ross Garnaut and Ligang Song (eds) The Turning Point in China’s Economic Development, Asia Pacific Press at the Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200.

Economics Unit, Asian Development Bank PRC Resident Mission (2004), “Suggestions on Setting Up Rural

‘Dibao’ System and Resolving the Problem of Feeding and Clothing The Rural Poor Entirely”.

Khan, Azizur Rahman (1998), ”Povetry in China in the Period of Globalization: New Evidence on Trend and

Pattern”, Issues in Development Discussion Paper No.22, Development Policies Department, International Labour Office, Geneva.

Lin, Justin Yifu, Fang Cai and Zhou Li (1998), “Competition, Policy Burdens, and State-Owned Enterprise

Reform”, American Economic Review/AEA Papers and Proceedings, Vol.88, No.2, pp.422-427.

Park, Albert (2007), “Rural-Urban Inequality in China”, in Shahid Yusuf and Tony Saich (eds) China Urbanizes: Consequences, Strategies, and Policies, the World Bank, Washington. D. C.. Park, Albert, Sangui Wang and Guobao Wu (2002), “Regional Poverty Targeting in China”, Journal of Public Economics 86, pp.123-153.

Psacharopoulos, George, Samuel Morley, Ariel Fiszbein, Haeduck Lee and William Wood (1995), “Poverty

and Income Inequality in Latin America During the 1980s”, Review of Income and Wealth, Vol.41, No.3, pp.245-264.

Ravallion, Martin and Shaohua Chen (2004), “China’s (Uneven) Progress Against Poverty”, World Bank Policy Research Paper 3408, Development Research Group, World Bank, Washington, D.C..

Roberts, Kenneth (2006), “The Changing Profile of Chinese Labor Migration: What Lessons Can the Largest

Flow Take from the Longest Flow?”, in Cai, Fang and Nansheng Bai (eds) Labor Migration In Transition China, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Wang, Meiyan (2010), “The Rise of Labor Cost and The Fall of Labor Input: Has China Reached Lewis

Turning Point?”, China Economic Journal, Vol.3, No.2, pp.137-153.

World Bank (1998), China in 2020: Development Challenges in the New Century, Beijing: China Financial &

Economic Publishing House.

Wu, Zhigang and Hengchun Zhang (2010), “The Characteristics of Migrant workers’ Employment And Its

Changes”, in Cai, Fang (eds) Reports on China’s Population and Labor No.11: Labor Market Challenges in the Post-Crisis Era, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

扫描下载手机客户端

地址:北京朝阳区太阳宫北街1号 邮编100028 电话:+86-10-84419655 传真:+86-10-84419658(电子地图)

版权所有©中国国际扶贫中心 未经许可不得复制 京ICP备2020039194号-2