2011.08-Working Paper-China’s WTO Accession, Agricultural Trade Liberalization and the Impacts on Rural Poverty

China’s WTO Accession, Agricultural Trade Liberalization and the Impacts on Rural Poverty

Tian Weiming China Agricultural University

Introduction

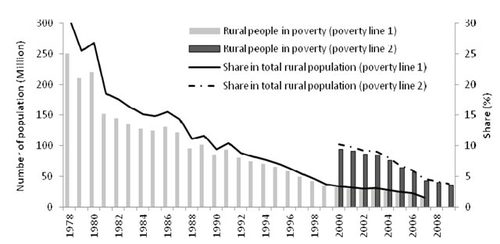

Elimination of poverty has been one of the prioritized policy objectives of the Chinese government since the early 1980s after China entered the era of opening and reforms. During the past three decades, China was successful in reducing the number of rural poverty population under an increasingly liberal trade environment. According to the official statistics, China’s rural poverty population declined from 250 million in 1978 to 36 million in 2009, or from about 30 percent to less than 4 percent of the rural population (NBS, 2009; 2010) 1 . This remarkable

accomplishment has been achieved in parallel with China’s dramatic leap in foreign trade. According to WTO (2010), China by 2009 overtook Germany as the largest merchandize exporter in the world, and ranked second to the United States in merchandize import. China also becomes a major trader in agricultural products, ranking fourth in export and second in import by 2008 (WTO, 2009).

The fact that reduction of rural poverty in China occurred simultaneously with gradual liberalization of agricultural trade aroused interests to look into the relationship between them (e.g. Anderson, 2002; Litchfield et al. 2003; Huang et al. 2005; Liu, 2007; Dollar, 2008; and Ravallion, 2008). This paper is a new attempt for ex post assessment on China’s experience of fighting against rural poverty under the gradually institutionalized open-trade regime. The major objective is to identify the roles of China’s increasing integration with the world agricultural market on rural poverty reduction using empirical evidences. Such information is relevant for both academics and practitioners worldwide in the cause of fighting poverty.

The paper is structured as follows: In the next section, the conceptual framework and methodologies used in this study are described. Then the paper describes China’s policy measures to cope with expected impacts of WTO accession. The fourth section explains China’s agricultural trade performance after WTO accession. The fifth section explores the linkages between poverty and trade liberalization empirically. The final section discusses China’s experiences and lessons learnt that may be useful for other countries.

Conceptual framework and methodology

In essence, rural poverty corresponds to weak capacity of rural people to earn incomes, which is determined in turn by either low labor productivity or institutionalized marketing and financial arrangements that discriminate against rural people. In most developing countries, agricultural production is carried out by smallholders, which are subsistent in nature. Their production capacity is severely capped by limited agricultural resources and poor ability to adopt new farming techniques due to human capital constraints. It is quite common that rural people in developing countries are often discriminated under the existing institutions in the forms of oppressive practices by various domestic monopolies in agricultural marketing and financial sectors, inadequate access to necessary public

services, restrictions on mobility of rural labor, and unequal voice in the political process. As a result, rural people often cannot secure their fair share in the outputs. Although the above characteristics are common in developing countries, the actual situation differs greatly in different countries, leading to varied importance of these factors on rural poverty.

According to the classic trade theory, trade liberalization leads to structural adjustment of production and trade in line with real comparative advantages of a country. The most important outcome from such structural adjustment is an increase in aggregate incomes due to productivity improvement of domestic resources. While consumers are in general better-off from increased supply and diversity of goods and services, the impacts on producers vary depending on whether they work in export industries or in import industries. In practice, it is quite often the case that import substituting industries suffer from enhanced competition after opening domestic market. As a result, returns to factors that are used intensively in these industries tend to decline. In a static framework, it can be inferred logically that trade liberalization may lead to enlarged income disparity provided the losers are not compensated with income transfer policy measures.

However, the picture may differ in a dynamic framework. Opening of domestic market may facilitate injection of foreign capitals and expertise, which helps to raise domestic production capacity. Domestic firms may face potential gains for scale economy. All of these changes are conducive to improvement of productivity and competitiveness of

the domestic industries with comparative advantages. Although such changes may help to halt monopolistic power of domestic firms, it opens avenues for multinational corporations to penetrate the domestic market and their direct economic and political influences on host countries.

In principle, if a country chooses to open the market based on its own desire and in a self-determined way, it is very likely that trade liberalization makes the country better-off. However, such a situation may not fully apply under the current multilateral trade system. A major accomplishment of the Uruguay Round of negotiation is the establishment of a “rule-based” multilateral trade system. While this system helps removal of major barriers and uncertainties to trade development, it requires that member governments accept in a package, all rules and disciplines embodied in the Uruguay Round Agreements. The shrunk policy space of member governments imposes restrictions on their capacity to cope with shocks in line with their specific conditions and policy priorities. Under such a circumstance, some countries with weak economic power and inadequate governance may be incapable to cope with the changes resulted from trade liberalization. Should social unrests occur, process of socioeconomic development could be

disrupted in an undesirable way. Given such a reality, gains from trade cannot be autonomously guaranteed even at the aggregate level.

The above analysis is particularly relevant to agricultural trade liberalization of developing countries. Agriculture is still a key sector in many developing countries in terms of both income and employment generation, although the share of agricultural sector in national economy has declined universally in the development process. Considering

that a healthy growth of agricultural production lays the foundation for social stability, how to cope with negative outcomes resulted from opening domestic agricultural market becomes a sensitive issue to policymakers in developing countries.

The present world agricultural market is still dominated by a few large exporting countries, most of which are developed economies, such as the United States, Canada, Australia and EU. The high competitiveness of the large commercial farms in developed countries comes from not only abundance of agricultural resources, advanced technologies and scale economy, but also from effective financial and other support granted by the governments and established control over global market chains via multinationals based in these countries. Given such a circumstance, improving access to overseas markets becomes the core interest of farmers and agribusinesses in such countries. In contrast, the smallholding household farms in developing countries suffer from inefficiency related to backward farming techniques, poor infrastructure, scale diseconomy, inadequate access to market information, and high transaction costs in dealing with commercial firms. In a majority of developing countries, the comparative advantages in farming tend to be eroded gradually in the dynamic process of socioeconomic development due to

irreversible transfer of resources to non-agricultural sectors and growing opportunity costs of labor. Consequently, the world agricultural trade is to a large extent characterized by flows of bulk commodities from developed countries to developing countries. Such a trade pattern means that most developing countries may face downward pressure

for prices of the traditional agricultural products and declining farm income after opening domestic market, although some of them may gain from increased exports of labor-intensive farm products. Such a situation is a major policy concern of the governments in many developing countries.

The most noticeable channel for transmitting impacts of opening market on rural income and livelihood is

price transmission from border to the domestic market. In principle, domestic prices should be fully aligned with border prices under liberal trade regime with the exchange rate being an affecting variable.However, in real world, price transmission can be impeded by tariff and non-tariff measures at the border, as well as by domestic marketing

arrangements and regulations. In countries with large territories, price transmission is less rapid and complete in regions distant from major ports, leading to varied regional impacts within a country.

How changes of prices in border affect rural livelihood depends on what products rural households produce. In reality, agricultural sector can produce exportable products, import substituting products and non-tradable products. Opening domestic market for competition may result in a decline of prices for import-substitution products and

increase of prices for exportable products. Meanwhile, prices of farm inputs may change as well, leading to variations of production costs. Therefore, trade liberalization may have both positive and negative impacts on farm incomes, depending on specific characteristics of the production system, although prices of modern inputs are more likely to

decline in most developing countries considering their backward systems for means of production.

Under the post-Uruguay Round world trade system, trade liberalization takes place in all economic sectors. Potentially, this offers developing countries an opportunity to expand exports of labor-intensive products to overseas markets, particularly those using more unskilled labor in production. Should this happen, off-farm employment for rural labor, as well as their wage incomes, would increase after trade liberalization. Potentially, rural households may be benefited through so-called “trickle down” effect related to improved national economic growth, which may take the forms of increased domestic demand for farm produce as well as increased earnings from off-farm employments. However, the past experiences show that it is not easy for developing countries to realize this potential given that many developed countries replace tariffs with new barriers in the name of quality and safety standards,

environmental standards and social welfare requirements.

In some developing countries, governments raise fiscal incomes primarily from tariffs on tradable goods. It is quite often that when tariff revenues declined due to tariff reduction, the government may raise domestic taxes or reduce outlays on state-funded projects and public services of lower priority. Unfortunately, rural development and

poverty alleviation often belong to this category, leading to potentially negative impacts on rural development and poverty alleviation.

Trade liberalization increases the weights of foreign shocks relative to domestic shocks in the determination of domestic welfare (Dan Ben-David et al. 1999). Many developing countries are vulnerable to sharp changes in prices of agricultural products due to inadequacy of governance. Therefore, the characteristics of domestic policy and institutions become key elements in determining whether a country can enjoy the benefits of trade liberalization. In the developing world, conducts of governments vary greatly in coping with the problems arisen from trade liberalization, leading to different performances in development of agricultural trade and rural economy.

Developing countries commonly face with foreign exchange constraints in the initial stages of development and agricultural exports are often the major source of foreign exchange earnings. In this stage, taxing agriculture to support modern industries is a common practice, including China. This is usually an important factor leading to

depressed agricultural prices and rural incomes. However, when a country is able to launch the development process, it may turn to earn foreign exchanges from mainly exporting non-agricultural products. In some case, “Dutch disease” may occur, leading to adverse impacts on agricultural production and farm incomes. Under such a circumstance, facilitation of factor mobility across economic sectors becomes a crucial element for sustained income growth of rural people. This fact has important policy implication to policymakers, namely the narrow agricultural policies will no longer work effectively in solving problems of rural income growth and poverty alleviation. In other words, growth of rural incomes becomes increasingly dependent on performance of national economy.

How rural poverty is likely to be affected by trade liberalization is a complicated issue. In many developing countries, most of rural households in poverty are resource poor, live in areas with inferior natural environments, are relatively insulated from major commercial markets due to poor infrastructure or remoteness, and lack needed skills for off-farm employments. The households in poverty commonly face difficulties in raising agricultural production.

Even though export of value-added farm products may be increased as a result of trade liberalization, they have limited opportunities to participate in such activities. Similarly, they also face difficulties in earning income from off-farm jobs. Under such circumstances, the rural people in poverty may have to remain in the shrunken farm sector after opening of domestic market, rather than move to activities with high labor productivity. In short term, whether

rural people in poverty become worse off depends on if changes in input and output prices at border can be transmitted effectively to inland areas where the poor live. In the longer term, rural households in poverty may be benefited from introduction of new farming techniques, improvement in marketing efficiency for farm inputs and produce, and injection of external capitals that create new jobs locally. In certain circumstance, these changes may reshape the dynamics of rural development and bring poverty households out from the trap of “poor but efficiency”

status.

Given the complexity of rural poverty phenomenon, it is not a surprise that empirical studies reveal no confirmative relationship between agricultural trade liberalization and rural poverty. To a large extent, the stories are country specific, depending on a wide range of known or unknown factors. Even within the same country, the aggregate effect may differ as well by regions and by periods as many affecting factors vary across regions or change over time. Farole, at al. (2010) addressed that a country’s participation in exports is just an intermediate measure of success and a more important question is how a country translates trade into economic growth and poverty reduction. One leading indicator may be the degree to which a country’s export sector is integrated with its wider economy, particularly through forward and backward supply linkages. Agricultural sectors offer significant potential for

developing deep value chains. However, in many low income countries, the constraints to competitiveness make long value chains untenable, restricting exports to unprocessed or minimally processed commodities and some niche higher‐value products where entire value chains can be controlled by a single agent. Besides, the infrastructure and skills needed to process raw materials are different from those needed to extract them.

Dollar and Kraay (2004) examined the effects of globalization on inequality and poverty using cross-country data. They found that changes in trade volumes have a strong positive relationship to changes in economic growth rates. Furthermore, there is no systematic relationship between changes in trade volumes and changes in household income inequality, meaning that the increase in growth rates leads on average to proportionate increases in incomes of the poor. They conclude that globalization leads to faster growth and poverty reduction in poor countries.

Balat et al. (2008) conducted an investigation on the relation between production of exportable crops and poverty alleviation. They found that farmers living in villages with fewer outlets for sales of agricultural exports are likely to be poorer than farmers residing in market endowed villages. Households engaged in export cropping are less likely to be poor than subsistence-based households. The authors conclude that the availability of markets for

agricultural export crops helps realize the gains from trade. This result uncovers the role of complementary factors that provide market access and reduce marketing costs as key building blocks in the link between the gains from export opportunities and the poor.

Dan Ben-David et al. (1999) addressed the difficulties in studying relationship between trade and poverty. They recognized that the primary problem was how to measure trade liberalization and poverty. They pointed out that there are many reasons why people are poor and there are huge differences in circumstances between individual households. Consequently, trade liberalization can have both positive and negative effects on poverty. They suggest that if poverty alleviation is a major goal of national policy, it is important to think how international trade policy can be harnessed to assist it.

Litchfield et al. (2003) proposed a framework for analyzing the relationship between trade and poverty using multi-period household survey data from Vietnam, China and Zambia as examples. The econometric model estimated using a panel dataset on 3311 households in rural Sichuan between 1991 and 1995 revealed that changes in household income were generally a much more important reason for movements in and out of poverty than changes in household composition. A higher grain quota price or market price significantly reduces the probability of entering poverty, and being a net seller of grain greatly increases the chance of exit. Households who are both net sellers and who live in areas with high grain market prices substantially reduce their risk of entering poverty.

Topalova (2004) uses India as a case to assess effects of trade policy changes (represented by tariff rates) on poverty (represented by headcount index and poverty gap index). The result revealed that there was a negative correlation between rural poverty incidence and tariff rate. However, this negative effect is relatively weak in regions with high labor mobility, indicating that the policy and institutional barriers to inter-sector labor transfer prevent structural adjustment of economy in response to changing market environment.

Based on large multi-country and multi-period household survey datasets, Ferreira and Ravallion (2008) described firstly the recent trends in poverty and inequality around the world and then estimated empirical relationship between economic growth, poverty and inequality dynamics. They find stylized facts: 1). that although developing countries have high income inequality, growth rates among developing countries are virtually uncorrelated with changes in inequality levels; 2). that economies that grew faster reduces absolute poverty much more rapidly; and 3). that inequality tends to reduce the growth elasticity of poverty reduction.

Dollar (2008) discussed what African countries could learn from China’s experience in poverty alleviation.

He pointed out four important features in China’s post-reform period, namely pragmatic approach for reforming policies and institutions, openness to foreign trade and direct investment, development of high-quality infrastructure, and continued support to agriculture and rural development combined with rural-urban migration.

Ravallion (2008) summarized lessons for African countries from China’s experiences in poverty alleviation. As he stated, two lessons stand out. The first is the importance of productivity growth in smallholder agriculture, which will require both market-based incentives and public support. The second is the role played by strong leadership and a capable public administration at all levels of government.

Huang and et al. (2005) use CAPSim model to simulate the potential impacts of trade liberalization on agricultural production, regional rural incomes and poverty in the period of 2001 to 2010. They found that although trade liberalization had positive impacts on China’s agricultural sector as a whole, not all rural households gained. In general, rural households in poverty benefited much less than average, leading to enlarged income disparity between regions and rural households.

How changes in border prices affect inland markets is an important issue to identify impacts of trade liberalization on rural poverty population in the case of China, given the fact that a majority of the rural poor reside in western provinces at a long distance from large commercial markets and underdeveloped transportation and communication systems. A major policy concern is whether rural poverty would become worse off given that the prices of many land-intensive commodities were expected to decline after trade liberalization. Several empirical

studies on food price transmission using co-integration method found that China’s regional markets were well integrated and the domestic market was also highly integrated with the world market (e.g. Zhou, Wan and Chen, 1997; Tian, 1998;

Huang et.al. 2004; Wu, 2000). These results seem to indicate that rural incomes in the inland areas are

not immune from external shocks. While such information is important to policymaking, the studies are commonly flawed by using prices observed either from the capital city of each province or simple average prices collected from several local assembly markets, which are not representative to prices the poor farmers receive in farm gate.

A majority of the studies in this area use the theoretical framework of pure market economy with all inputs and outputs being valued at prevailing market prices. However, in China, as well as in many developing countries, most rural households in poverty have limited capacity to produce farm products in appropriate volumes. In fact, a significant amount of poor households live barely at the level of subsistence and are essentially disconnected from

commercial markets. As a result, changes in prices of farm produce cause largely nominal changes in income and consumption rather than wellbeing of rural people in poverty. This means that whether the commonly used poverty indicators derived from nominal income or expenditure statistics can reflect real situation is a question.

In order to assess impacts of trade liberalization on rural poverty, knowledge about the specific conditions of poor households are important. The information needed includes the household resources owned, the bundle of products produced, capacity to respond to changing price signals, mobility of resources (particularly labor), technical

and institutional constraints to structural adjustment, household consumption pattern, etc. However, micro-level datasets are not easily accessible in practice. As a result, econometric methods focusing on household responses to the changing market environments are relatively limited. Even where observations are available over time, it has so far proved difficult to disentangle the effects of trade and agricultural liberalization from other contemporary shocks. Instead, many studies use cross country or regional panel data to investigate dynamic changes in rural poverty. However, panel datasets are often constructed without specific focus on poverty phenomenon and related determinants, leading to elective variable inclusion and model specification.

China’s coping policies to opening agricultural market

In the late 2001, China was finally acceded into the WTO after the 15-year negotiations. For the sake of WTO accession, China made profound commitments on opening domestic market for competition. Given the anticipation that China was very likely to become a major importer of agricultural products in future, the major agricultural exporting countries placed their targets on achieving substantial liberalization of China’s agricultural trade. With respect to agricultural trade, the final protocols agreed included commitments on reducing import tariffs, eliminating

all SPS and TBT barriers without sound scientific basis, ceasing export subsidies, and capping domestic support within allowed de minims (WTO, 2001). China was allowed to use tariff-rate quota system to manage imports of some sensitive commodities, such as cereals, vegetable oils, cotton, sugar and wool. However, specific disciplines were set to bind the government and state trading enterprises (STEs), including that certain proportions of quotas must be allocated to non-state trading entities and that unused quotas by STEs must be redistributed to other end users within a calendar year. China also accepted the condition that other members could use transitional safeguard measures to protect their domestic industries from potential injury by surging of import from China. As a consequence, while China committed to opening its agricultural market substantially, it allowed many barriers intact with regard to access to overseas markets. In essence, implementation of the commitments would lead to enhanced integration with the world market and shrunken policy space for the government to intervene in the agricultural

market. Therefore, the WTO accession would impose great challenge to the Chinese government for ensuring national food security and growth of rural incomes.

The potential impacts of China’s commitments on agricultural and rural economy received wide attentions by policymakers before and after the WTO accession. Many studies (e.g. Wang, 1997; College of Economics and Management, 1999; Martin, 1999; Cheng, 2000; Huang, 2000; USDA, 2000; Gilbert and Walh, 2000; Walmsley et al 2000; Zhai and Li, 2000; Sun, 2001) using various analytical tools revealed that, after WTO accession, China would increase imports of a wide range of land-intensive commodities with a growing reliance on imported food and other agricultural products, although exports of some labor-intensive products might grow as well. The prices of major agricultural products would decline, leading to negative impact on rural incomes and poverty. Such a situation required the government to take coping measures promptly and effectively.

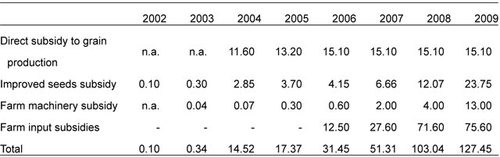

In responding to the anticipated negative impacts, the Chinese government introduced a series of new policy measures to support agricultural sector upon accession to the WTO accession. Starting from 2004, the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee issues the so-called “No. 1 Document” annually, which highlights the general guideline for agricultural and rural development in each year, and puts forth policy measures accordingly.

The policymakers recognized that the enlarged polarization of urban-rural incomes became very harmful to social stability and must be prevented from worsening further. The idea that China has entered second phase of development that is featured by industry nurturing agriculture and cities supporting the countryside is formally accepted by the government as a principle to guide the future agricultural policies. A series of measures have been implemented or announced, covering technological research and extension, reduction and full removal of taxes on agriculture, increased financial support to agricultural production, growing state investment on rural infrastructure in underdeveloped areas, promoting industrialization of agriculture, enhancement of farmland protection, improvement of rural education and health care, and extension of democracy at grass-roots level. All these measures are driven by the consideration to ensure lasting social stability and unity. In the past decade, the national government has substantially increased fiscal appropriations for supporting agricultural and rural development (see Table 1).To some extent, these policies can be justified by principles of economics since agriculture generates some positive

externalities to the society (OECD, 2001; Tian 2003; FAO, 2004).

Table 1 China’s agricultural subsidy in 2002-2009 (RMB billion)

Source: Calculated by author from various publications by the Ministry of Finance.

Some of the policy programs have direct or indirect impacts on rural poverty. For instance, the government introduced so-called “grain for green” program in 2000, under which a total of 6.51 million hectares of cultivated lands in some environmentally fragile areas were turned into pasture, forestry or lakes. The farm households who owned lands were compensated with both cash and grains. Given the fact that China’s rural people in poverty are

concentrated in the project areas, implementation of this program may impact their livelihood to some extent. Similarly, funding from central government budgets to construction of infrastructure and upgrading educational and medical facilities in western regions may generate indirect benefits to the rural poverty people. However, the policy

programs of abolishing agricultural taxes and provision of subsidies to producers may not benefit the rural poor significantly.

China instituted rural poverty alleviation program in the early 1980s with the help of some international organizations, such as the World Bank. The government enhanced endeavor after the WTO accession. Apart from the previous programs focusing on improving agricultural production capacity, the government began to devote more

resources on various rural social services that had longer term positive effects on agricultural and rural development and poverty alleviation through improvement of human capital. The major measures include extending rural education and cooperative health services, introducing rural social welfare programs as a safety net for rural people.

Microcredit programs have been extended actively aiming at removal of financial constraints faced by the rural poor. Natural disaster relief and subsidized agricultural insurance have been basically institutionalized. Improvement of rural infrastructures in underdeveloped regions is also given high priority. However, the effectiveness of such efforts is sometimes impeded by incapability to provide complementary funding and poor governance of local governments.

Performance of China’s agricultural trade development

As a result of these policy measures, China has been able to achieve sustained strong growth of both national economy and agricultural production after the WTO accession. According to the official statistics (NBS, 2009 and 2010), during the period of 2002-2009, the gross value of agricultural production grew at an annual rate of 5.2% in real terms, which was slightly lower than the average growth rate during 1980-2001, but higher than that of 1999-2001. Driven mainly by the growing domestic demand, livestock and fishery production increased more rapidly. Horticultural production grew at the highest rate among crop products. China’s grain production turned from stagnating low levels in the period of 2000-2003 into a steady rise thereafter. Outputs of cotton and oil-bearing crops also maintained upward trends, although notable fluctuations occurred. Meanwhile, the rural laborers have been employed increasingly in the labor-intensive manufacturing industries and thus have earned more incomes apart

from farming. As a consequence of the above changes, rural incomes grow strongly and continuously, leading to welfare improvement of the rural households. It can be concluded that China is quite successful in adapting to the new trade environment by adjusting the economic structures in line with its comparative advantages.

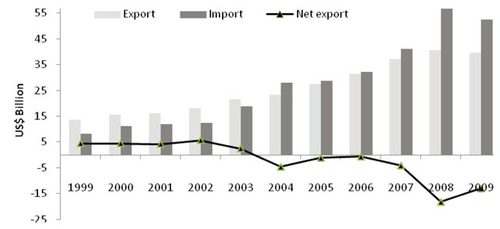

After WTO accession, China’s agricultural import and export grew at an unprecedented high rates continuously until the 2008 world financial crisis caused a downturn (see Figure 2). During 2002-2008, total value of agricultural exports rose from $18.15 billion to $40.50 billion, while that of agricultural import rose from $12.45 billion to $58.66 billion. China became net importer of agricultural products in 2004 and the deficit tended to grew over time.

Figure 1 Changes in China’s agricultural trade in 1999-2009 (US$ billions)

Note: The coverage of agricultural products here is defined as that included in Uruguay Round Agreement on

Agriculture plus fishery products. The data are reported by Ministry of Agriculture (2010).

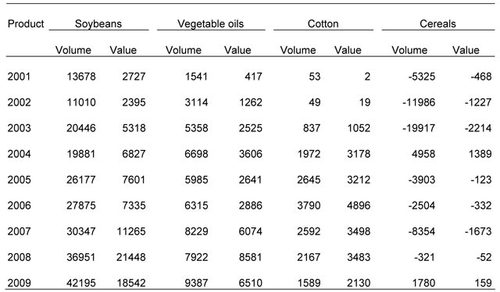

The turning of China’s agricultural trade from net export to net import is closely related to deterioration of trade position for a few commodities, mainly soybean, vegetable oils, cotton, and cereals (see Table 2). The trade deficit in soybean is by far the largest single item, amounting nearly $20 billion in recent years. Trade deficit of vegetables oils ranks second, peaking at $8.6 billion in 2008. China’s trade position in cotton is closely related to overseas

demand for textile and clothing products. The complete removal of MFA in 2005 apparently offered China a promising opportunity for expanding export of textile and clothing, which became a factor leading to notable increases in imports of cotton and other fibers. However, this anticipation did not become a reality since some major importers began

to use transitional safeguard mechanisms to prevent surging of Chinese products. The volume of cotton import declined gradually after 2006 due to both insufficient demand and increased domestic supply. China was able to remain net export position in trade of cereals in most of the years. To some extent, the temporary reversals in cereal trade position in 2004 and 2009 were caused by the policy measures coping with the soaring food prices then.

Table 2 China’s net imports of selected land-intensive commodities (thousand tons and $ million)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture (2010).

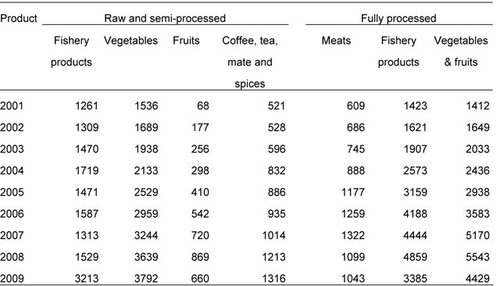

On the other hand, entering the WTO provides China with improved access to overseas market as well. As

a result, China was able to expand export of a wide range of agricultural products to some premium markets like Japan, US and EU. The best performed agro-industries include raw and processed vegetables, fruits and fishery products (see Table 3), which are all featured by high labor intensiveness

Table 3 China’s net exports in selected labor-intensive commodities (million $)

Source: Ministry of Commerce (2010).

On the other hand, entering the WTO provides China with improved access to overseas market as well. As

a result, China was able to expand export of a wide range of agricultural products to some premium markets like Japan, US and EU. The best performed agro-industries include raw and processed vegetables, fruits and fishery products (see Table 3), which are all featured by high labor intensiveness

The statistics above reveal that the changes in China’s agricultural trade patterns are basically consistent with China’s comparative advantages. The rapid expansion of agricultural exports can be partially attributed to improvement in agricultural productivity resulted from both private efforts and government promotion. On the other hand, the strong growth in agricultural imports has been driven by growth in both domestic consumption demand

and production inputs induced by expansion of exporting value-added agricultural products.

To some extent, the outcomes are not fully consistent with the initial prediction. The first and foremost deviation is trade in cereals. A prevailing view was that China lacked comparative advantage in cereal production and thus should import cereals in large volumes after opening the market. However, China has been able to increase cereal production via enhanced policy support. As a result, China maintained essentially basic self-sufficiency in

cereals during the whole decade after WTO accession.

The second major deviation is in trade of livestock products. China was traditionally a low cost producer

of a wide range of livestock products. It was predicted by some that China might increase export of livestock products as a result of improved access to overseas markets, especially in the growing Asian markets (Huang 2000). However, this potential was not realized due to both the strong growth of domestic demand and the non-tariff barriers set by major importing countries in the forms of food safety regulations, environmental standards, animal welfare, etc. As a result, China has turned from a net exporter to a net importer in unprocessed meat products in recent years.

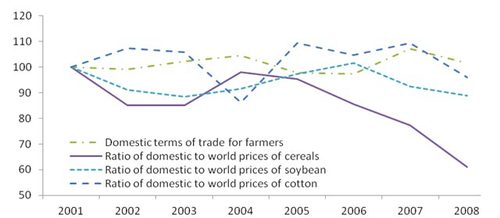

Figure 2 depicts changes of several price ratios during the period of 2001-2008, It reveals several important characteristics from the pattern of price changes: 1). The domestic terms of trade for farmers was relatively stable; 2). The domestic prices of cereals were partially delinked from international prices, particularly in 2008 when the world prices soared; 3). Although there were notable fluctuations, the domestic prices of soybean and cotton moved

roughly in parallel with the world prices; and 4). The transmission of world prices to China’s domestic market is incomplete and varies by commodities.

Figure 2 Changes in ratios of major prices during 2001-2008

Note: Domestic terms of trade for farmers is the ratio of price received for farm produce to price of paid for

means of agricultural production.

The above outcomes are partially caused by policy interventions of the Chinese government. For instance, the government instituted state procurement at guaranteed prices for major cereals and oilseeds, and use state reserve schemes to adjust supply-demand balances. It should be noted that not all of those intervention measures are designed to support farmers. The recent experiences suggest that, although improvement in rural income has been stressed constantly by the Chinese leaders, securing national food security and imagined social stability are always more prioritized policy objectives. This policy bias was clearly demonstrated in the recent world financial crisis

when the government took measures to discourage exports and encourage imports in order to cope with inflation pressure attributed to external shocks of soaring world prices. Although the measures did help to check food price rising in domestic market, it reduced farm incomes.

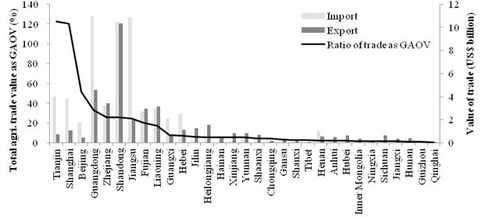

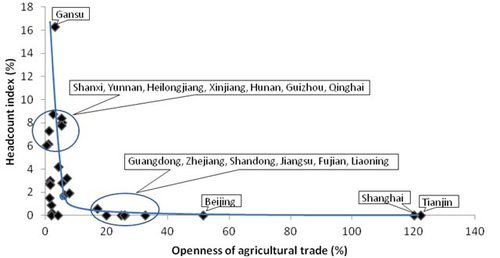

The price transmission may be further dampened by limited involvement to foreign trade of the inland provinces. Figure 3 ranks all of the provinces according to openness of regional agricultural market, which is defined by ratio of total value of agricultural trade to gross agricultural output value by province2. As it shows, provinces characterized

by high openness in agricultural markets include the three old municipals and several coastal provinces with prosperous regional economies, such as Shandong, Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Fujian. In contrast, most of the inland provinces remain in their inward-looking mode of agricultural development. Under such a circumstance, trade liberalization may impact inland regions via mainly spillover effects generated from coastal regions. As a result, the external shocks may be partially neutralized before reaching the inland regions.

Figure 3 Regional variations in openness to agricultural trade in 2008

Source:

NBS (2009); MOA (2009).

China’s experiences of agricultural trade development in the post-WTO accession period have important implications to agricultural development and rural poverty alleviation.

Firstly, the growing dependence on trade makes China increasingly susceptible to external shocks. Therefore, improving governance of world agricultural trade should be taken as core content in China’s agricultural and rural development strategy.

Secondly, the growing agricultural trade deficits indicate that China’s competitiveness in agricultural products is eroded gradually. Under such a circumstance, to tie the farmers on land can only make them worse off, leading to enlarged urban-rural income disparity and deterioration of rural poverty problem. There is a clear tradeoff between raising agricultural production and rural incomes.

Thirdly, it can be observed that the compositions of agricultural products China imports and exports differ notably, meaning that those farmers who produce high-valued products gain from trade liberalization, while those who stick to the traditional land intensive products may lose due to competition of imported products. Similarly, those products are also produced in different regions, leading to regional variations of impacts. This means that the distributional effects of gain from liberalizing agricultural trade are likely far more important than the net welfare change at the national level.

Potential impacts on rural poverty alleviation

As addressed in the previous sections, impacts of trade liberalization on rural poverty may vary across regions and households. Therefore, it is useful to know the major characteristics at locality and household levels. Detailed information of household in poverty is not easily accessible. However, such information is revealed by some official publications, such as Poverty Monitoring Report of Rural China published annually by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS, 2009). The description below uses mainly information from it. It should be noted that China’s official statistics are far from complete. Moreover, the data are not collected and compiled in a consistent manner, sometimes leading to problem of incompatibility. Therefore, the description should be taken with due caution.

As revealed in Poverty Monitoring Report of Rural China, the rural households in poverty have the following characteristics (NBS, 2009): 1) limited agricultural resources, often of inferior quality; 2) large-sized families with more elders or children; 3) low educational level of family members; 4) high dependence on farming for incomes with limited cash earning; and 5) having highly subsistent household economy. At locality level, areas with high poverty incidence are often characterized by: 1) inland areas with limited access to major commercial markets due to underdeveloped rural infrastructures; 2) areas with fragile ecological environments, such as severe soil erosion or desertification, sustained water shortage, frequent occurrence of extreme weather, etc.; 3) limited injection of financial and human capitals; and 4) weak government fiscal power and poor governance of regional development. These characteristics are crucial in determining local competitiveness in production and thus the nature of impacts on rural poverty caused by trade liberalization.

In the late 1970s when China initiated policy reforms, the level of rural income was very low, but income distribution was quite equitable. The Chinese government acknowledged officially phenomenon of rural poverty as a result of implementing the opening and reform policies in the early 1980s. Since then, the government has made great efforts to alleviate rural poverty with both domestic resources and external aids. As a result, the number of rural people under the official poverty line declined steadily from about 250 million in 1978 to 32 million in 2000 (NBS, 2009)3 as shown in Figure 4. (Amounts in RMB of the two poverty lines should be mentioned)

Figure 4 Changes in China’s rural poverty during the period of 1978-2008

Note: Poverty line 1 is the previous official poverty line, and poverty line 2 corresponds to the previous low-income poverty line. The data are reported by NBS (2009, 2010).

It can be seen from Figure 4 that the scale of rural poverty declined very rapidly in the early years of the reform era. This success was mainly the result of strong growth in agricultural productivity induced by introduction of the household production responsibility system as well as removal of major policy distortions unfavorable to agricultural sector via reforms on agricultural marketing. The improvement in terms of trade combining with productivity growth led to a widespread rise of rural incomes, which lifted many rural people out of poverty. Reduction of rural poverty was sustained in the period of late 1980s and whole 1990s. The outburst of rural non-farm activities played an increasingly important role in raising rural incomes. However, while rural poverty in areas with adequate conditions for agricultural production was alleviated continuously, the people in those remote, mountainous or arid areas met insurmountable difficulty to raise their incomes through both farming and off-farm activities. As a result, rural people in poverty tend to concentrate increasingly in those areas with inferior natural and economic conditions. During this stage, China’s agricultural trade was still largely controlled by the state. As a result, the government was able to manipulate the prices of both agricultural products and inputs based on policy considerations. The speed of decline in rural poverty seemed to slow down in the post-WTO accession period, although the general trend continued. This is understandable for the remaining rural people in poverty are those who reside in areas with the most unfavorable natural and economic conditions, and their physical and human capitals are also the most limited. This means that further reduction of poverty population must be at growing costs.

While the national statistics indicate clearly that the decline of rural poverty population in China has

occurred in parallel with strong increase in agricultural trade, no confirmative conclusion can be made from this superficial negative correlation given that many other factors changed as well. Although using household-level data may help to reveal behavior of how those poverty households respond to the changing market environments, it is difficult to evaluate the roles of trade openness on poverty since the linkages are indirect. Besides, such endeavors are constrained by data availability. A realistic approach is to use provincial data to assess empirically the relationship between poverty and trade liberalization with other variables being controlled.

In this study, we use rural income distribution data by province released by Ministry of Agriculture (2009a) to calculate indicators of inequality and poverty4. The data provide information of numbers of rural population within different income groups. The POVCAL software from the World Bank is used to calculate headcount index and Gini coefficient for each province5. The calculation covers the period of 1999-2008 on the basis of data availability and

compatibility consideration. The criterion of one dollar per day in PPP terms is used to derive headcount index, which is notably higher than China’s official poverty line for all years. Instead of the calculated mean incomes from Ministry of Agriculture’s data, the reported provincial per capita net incomes from NBS were used in deriving the provincial headcount indexes.

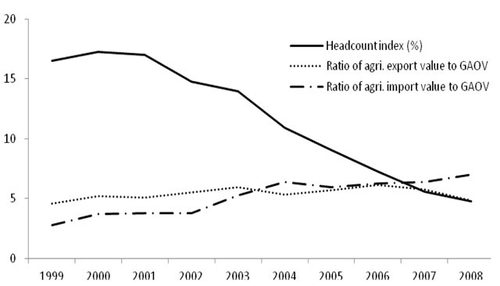

As shown in Figure 5, headcount index declined steadily after WTO accession. In fact, the speed of decline in headcount index was faster than the same indicator based on China’s official poverty line. It can be noted that the ratio of agricultural export value to gross agricultural output value rose gradually from 4.7 percent in 1998 to 6.1 percent in 2006 and then declined. In contrast, the ratio of agricultural import value to gross agricultural output value rose rather steadily over the whole period. In fact, the notable appreciation of RMB since July 2005 dampened the

upwrd movement of the two ratios.

Figure 5 Changes in rural poverty in the period 1999-2008

Note: Calculation by author using data from MOA (2009).

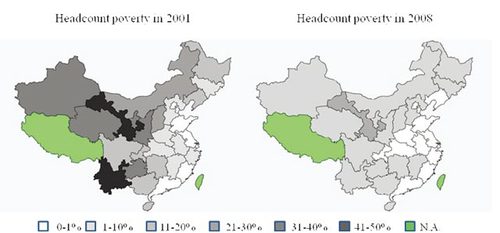

The relationship between openness of agricultural market and rural poverty can be further revealed through investigating the regional patterns of changes. Map 1 depicts regional pattern of rural poverty and its changes between 2001 and 2008. It can be observed that China’s rural poverty population was concentrated heavily in western region 6 in both years, where economic and ecological conditions are inferior. In fact, about two-thirds of the rural poverty population lived in western region according to NBS (2009). The central region and northeast region also have large poverty populations, but are proportionally much smaller than that in western region. In contrast, rural poverty is basically eradicated in eastern region where the regional economies are prosperous. Map 1 indicates that incidence of rural poverty declined universally between the two years. By 2008, only Gansu had a headcount index above 10 percent, while in 2001 there were nine provinces had a headcount index above 20 percent plus another

seven provinces within the range of 10 to 20 percent. Major agricultural provinces like Anhui, Henan and Hubei basically eradicated rural poverty, while the headcount index declined to about 3 percent or less in Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Jilin, Guangxi and Sichuan. Implementation of the policies to support development of the western region is an important contributing factor for rural poverty alleviation in provinces where China’s minority

nationalities live. Such a pattern of changes suggests that opening of agricultural market has not impeded China’s effort in eradicating rural poverty, although domestic factors may be more important in determining the changes.

Map 1 Changes in incidence of rural poverty by provinces between 2001 and 2008

Note: The indexes of poverty previlance are calculated by author using data from Ministry of Agriculture (2009).

The impacts of opening agricultural market on rural poverty can be further observed by looking at the relationship between openness in agricultural trade (defined as ratio of total values of import and export to gross agricultural output value) and poverty incidence using cross province data as depicted by Figure 6. A clear fact is that all points are located close enough to the left and right axes with an almost perfect L-shaped curve. Most northwest and southwest provinces fall into the upper-left part. Heilongjiang is a province with both relatively high poverty incidence (8.0%) and high openness (5.6%). A majority of provinces has both low openness and low poverty incidence. This seems to suggest that opening of agricultural market is not an important factor leading to deterioration of rural poverty problem in the case of China. On the contrary, it may be a factor contributing to poverty alleviation, although whether this causal relation is valid needs to be investigated with more rigorous methods.

Figure 6 Relationship between openness of agricultural trade and rural poverty in 2008

Note: MOA (2009) and author’s calculation.

Some empirical observations may help to explain the distinct regional patterns in trade openness and poverty. Taking the advantages of closeness to overseas markets and large injections of FDI and related managerial expertise, the coastal provinces like Shandong, Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang and Jiangsu are able to expand exports not only of labor intensive farm produce, but also of value-added processed or semi-processed products. This becomes possible partially due to these provinces increased imports of land intensive products used as both consumer goods and intermediate inputs in agribusiness sector. Such a structural adjustment has improved efficiency of resource utilization and thus made the farmers better off. In contrast, farmers in inland provinces are bound to produce traditional products with low economic returns. Furthermore, the coastal provinces may opt for low-priced imports, leading to reduced demand for products from inland regions. Under such circumstances, reduction of rural poverty in inland provinces becomes increasingly dependent on local economic growth, although they may be benefited somewhat from the so-called “trickle-down’ effect generated by growth of national economy.

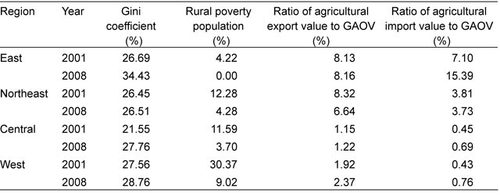

Table 4 describes changes in regional patterns of agricultural trade, rural income distribution and poverty by geographic regions. The data reveal that east and northeast regions have higher trade dependence than that in central and western regions. Inequality of rural income distribution does not differ significantly across regions, with the central region being an exception. Poverty incidence shows an ascending order from the east to the west.

The over time changes of these indicators also reveal important information. During the period of 2001 to 2008, rural poverty declined sharply and universally, although rural income disparity tended to be up in varying degrees among the four regions. During the period, ratios of agricultural export value to gross agricultural output value were relatively stable in most regions. Similarly, ratios of agricultural import value to gross agricultural output value were

also generally stable, except for east region where the ratio was more than doubled between the two years.

Table 4 Changes in trade, income distribution and poverty patterns by region

Note: Calculated by author based on statistics of NSB (2009), MOA (2009).

Both time series data and cross-sectional data indicate that there were a negative correlation between openness of agricultural market and rural poverty. However, whether this superficial relationship is valid statistically remains to be a question, given other factors have changed as well. In order to identify the possible impacts of opening agricultural market on rural poverty, a model using panel data is estimated covering the period of

1998-2008 with all provinces except for Tibet. The model is specified as (time and cross section subscripts are dropped for simplicity):

PHCI=f (RAE, RAI, RFS, RAT, RLE, RLA, AGDPS,TOT, GINI)

The variables are defined as:

PHCI = Poverty headcount index;

RAE = Ratio of agricultural export to the gross agricultural output value;

RAI = Ratio of agricultural export to the gross agricultural output value;

RFS = Ratio of fiscal support to agriculture to net income of rural population;

RAT = Ratio of agricultural taxes to net income of rural population;

RLE = Average level of rural labor education;

RLA = Share of rural labor engaging in agricultural production;

AGDPS = Share of agriculture in regional GDP;

TOT = Farmers’ terms of trade defined as ratio of price indexes of agricultural products to farm inputs;

GINI = Calculated Gini coefficient on the basis of rural net income;

In this model, the openness of agricultural market is measured separately by ratios of export and import values to the gross agricultural output value. Both trade theory and practical experiences suggest that increase of agricultural exports is conducive to growth of agricultural sector, while the opposite is true for increase of agricultural imports. This means that the two variables are likely to have opposite effects on rural poverty. Enhancement of fiscal

support to agriculture and reduction of taxes on agriculture may contribute to reduction of rural poverty. Education can increase human capital and thus raise productivity, resulting in improved income earning ability of rural people. Binding of rural labor to low productive agricultural production is a major factor leading to low rural income. In general, transfer of rural labor to non-farm activities results in increased rural income. Therefore, variable RLA is

expected to have a positive coefficient in the function. Similarly, regions depending more on agriculture may have lower income and severer rural poverty. Improvement of farmers’ terms of trade contributes to rural income and thus reduces rural poverty. Income distribution is dependent on a wide range of institutional and cultural factors, while Gini coefficient can be regarded as a proxy of such variables. With a given aggregate income, the larger is the income disparity, the more likely of the low income segment of rural people fall into poverty.

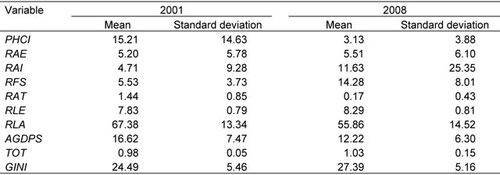

Table 5 shows the simple averages and variances of all variables in 2001 and 2008. It can be observed that import dependence (RAI) and fiscal support to agriculture (RFS) increased notably, but rural income disparity (GINI) also increased notably. Meanwhile, agricultural taxes (RAT), share of agricultural rural labor (RLA) and share of agricultural GDP (AGDPS) decreased significantly. Changes in export dependence (RAE), rural labor education (RLE) and farmers’terms of trade (TOT) seem to be trivial.

Table 5 Statistical characteristics of the variables in 2001 and 2008

Apart from variables abovementioned, rural poverty may have a region-related dimension. This is because households within the same region typically share some common socioeconomic characteristics, such as geographical locations, climatic and agronomic conditions, specific cultures, and demographic characteristics, which jointly determine the comparative advantages of regional industries, employments and incomes, as well as living standards of rural households. Given these factors are in general time-invariant, the effects can be controlled by adding cross-sectional dummy variables into model.

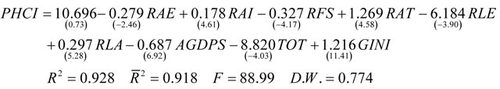

The possible existence of heterogeneity is taken into consideration by using cross-section weighted robust estimation method (PCSE). Test for redundant cross-section fixed effects is rejected at 1 percent of significance. The estimated model is shown as follows with the figures in parentheses are the corresponding t statistics7.

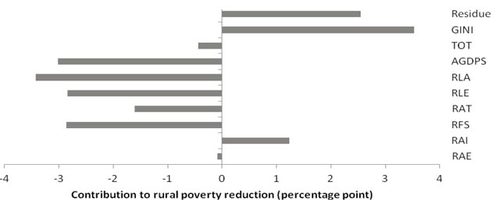

It can be seen that all of the coefficients have expected signs and are statistically highly significant. The high R-squared indicates that the model fits the sample data very well. The coefficients of variable RAE and RAI negative and positive respectively, implying that recent the deterioration in China’s agricultural trade position is unfavorable to rural poverty alleviation. Fortunately, the increases of import dependence are marginal in the central and western regions and the impact on rural poverty is not particularly large. The redirection of agricultural 7 The coefficients of fixed effects are not reported for simplicity. and rural policies after the WTO accession is a major contributing factor, leading to a 4.5-percentage point decline in rural poverty between 2001 and 2008. Improved rural labor education, transfer of rural labor to non-agricultural activities and structural adjustment of regional economies contributed 2.8,

3.4 and 3 percentage points to rural poverty reduction respectively. However, enlarged income disparity made the rural poverty problem worse, leading to a 3.5-percentage point increase. While the above results are sound in terms of economic logic, the implications should be taken with due caution. The major problem is that provincial data may not represent the real situation faced by the rural poverty population.

Figure 7 Decomposition of contribution to rural poverty reduction between 2001 and 2008

These results imply that agricultural trade liberalization is not a major factor affecting rural poverty, although the growing imports have had some negative impacts. The reduction of rural poverty throughout China should be attributed mainly to changes in government policies and economic structural adjustment. Improved rural labor

education is also important. In brief, domestic factors are more important than trade with respect to impacting rural poverty. Several facts may help to understand why the situation is as such.

Firstly, being a large country, China is not very susceptible to fluctuations in world prices. This is because, China’s domestic market is supplied mainly with domestic products and any notable increase of imports may lead to world price rising, which restricts automatically further growth of imports.

Secondly, areas with large rural poverty population are located mainly in remote inland provinces, which have weak linkage with major commercial markets both within and outside China. Besides, price transmission from border to such areas needs to pass through multiple market stages with significant lags. Therefore, agricultural trade liberalization may have no perceptible impacts on agricultural economy in such areas.

Thirdly, in such regions, development of commercial firms in general or agribusinesses in particular lags

far behind, leading to limited channel to link inland market and external markets. Elimination of this constraint takes time. Without an efficient marketing system, the poor rural households in underdeveloped regions cannot participate in worldwide competition in an effective manner.

Finally, the impacts on rural poverty households may be even weaker, for the subsistent nature of household economy makes them somewhat immune to external shocks.

Experiences and lessons learnt from China’s practices

The remarkable reduction of China’s rural poverty population during the past three decades reflects an

essential fact that China has been successful in improving labor productivity of those poor rural households with the gradual opening domestic market for competition. The following experiences can be summarized from China’s practices with respect to relations between trade liberalization and poverty alleviation.

Removal of domestic bottlenecks to productivity is more crucial than trade policy reforms

In the 1980s, the Chinese government carried out policy reforms represented by introduction of household production responsibility system and a gradual liberalization of domestic market. Such institutional changes brought about enthusiasm of farmers successfully, which turned out sharp increases of agricultural productivity. During this

period, China was largely isolated from the world market. It was at this stage that China realized unprecedented high rate of rural income growth, which in turn resulted in a rapid reduction of rural poverty countrywide. China’s experiences after WTO accession further support this idea. In order to cope with anticipated undesirable impacts of opening domestic market, the Chinese government introduced a series of policy measures to support agricultural and rural development in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Meanwhile, the government also devoted high attention to fostering domestic agribusinesses, which served as a bridge to link small household farms with commercial markets. With these measures, China was able to deal with competitiveness after opening the agricultural market.

Sustainable elimination of rural poverty cannot rely on improvement of agricultural productivity only

For rural poverty alleviation, improvement of agricultural productivity has a primary role whenever such potentials exist and demand is not restrictive. This was the actual situation when China initiated the policy reforms. However, the marginal effect of agricultural production growth for rural poverty reduction tends to decline due to mainly two facts: agricultural production is subject to diminishing returns with given resources and technologies; and demands for agricultural products have in general been low with declining income elasticity. Considering that poverty households are commonly resource scarce, the potential for raising agricultural production is often limited. Therefore, while expanding agricultural production helps eliminating absolute poverty, sustained increase of rural income must come from transferring rural labor to more productive off-farm activities. China’s increasing involvement of global supply chains on the basis of its real comparative advantages has lead to substantial expansion of manufacturing industries before and after the WTO accession, which creates millions of jobs for rural labor. Transfer of rural labor to off-farm activities helps to remove straitjacket to earning ability of rural people. More importantly, it represents a rationalization of resource allocation nationwide. However, in order to make this

happening in a healthy mode, government needs to take measures in improving rural education, training and information dissemination. All of these steps are not trade dependent, although opening of trade may be conducive to expansion of labor intensive industries and to provision of high-quality services.

Transformation of the smallholding system is a real challenge

It is a formidable task in agricultural and rural development to transform the current smallholding system into production units that are efficient enough to compete internationally to find an efficient way to integrate them into globalized market chain. Success or failure in this endeavor is crucial to not only China’s long-term position in agricultural trade, but also realization of the policy goal for a harmonized urban-rural development and poverty reduction.

China’s small household farms suffer from inefficiency in both production and post-production stages. Transformation of the smallholding system is also crucial for overcoming non-tariff barriers to agricultural products. The experiences show that costs for quality control are extremely high when raw products are supplied by numerous small producers. Considering the fact that consumers worldwide become increasingly conscious of food safety and

environmental sustainability, failure in responding to this trend may ruin completely China’s competitiveness in both domestic and overseas markets, even though China is able to maintain the cost advantages in agricultural production. Besides, effective implementation of the policies that are in compliance with WTO rules becomes problematic for the implementation costs are very high and leakages of benefits are large due to rent-seeking behaviors. However, scaled production becomes possible only if the released rural laborers can be absorbed by the

non-agricultural sectors. To some extent, China’s success in rural poverty alleviation can be attributed to implementing such a broad-based development strategy.

Maintaining steady growth of national economy and social stability are preconditions for rural poverty reduction

Starting from the early 1990s, the Chinese policymakers placed top priority on socioeconomic development. Since then, China has adhered market-friend policy reforms in order to foster fully the individual enthusiasm. Although there were some short term setbacks, China is able to maintain social stability, which is an essential condition for the steady growth of national and rural economies. As a result, the rural poor are benefited directly from

growth related job creation and indirectly from enhanced government financial assistance to the rural sector, leading to rapid reduction of rural poverty.

However, the increased openness creates some problems for macroeconomic stability as well. Under a freer trade system, macroeconomic stability is inevitably affected by trade performances. External shocks, such as the world financial crisis in 2008, have notable impacts on macroeconomic growth. It occurred in China that many migrant laborers were dismissed from factories and had to go home for living, leading to a sharp decline of incomes. A more profound issue for China is the so-called “Dutch disease”. The burst of export-oriented manufacturing

industries in the 1990s and 2000s led to continued trade surplus, and thus pressure for RMB appreciation. Being the traditional industries in national economy, agricultural sector is sensitive to revaluation of RBM, which may lead to not only deterioration in competitiveness of agricultural products, but also difficulty for the government to continue the current agricultural support policies given the binding by WTO disciplines. Such adverse changes in macroeconomic conditions would impact rural poverty negatively as well.

Improving governance is crucial for both trade and rural poverty alleviation

Apart from limited physical and human resources, labor productivity of the rural poor is also constrained by inadequate public services and poor governance. Starting from the early 1980s, the Chinese government devoted substantial resources for improving rural infrastructures, basic education, health care services, and dissemination of technical and market information. These efforts contributed substantially to many low income rural people to pull away from poverty through improved earning ability in both on-farm and off-farm activities.

On the other hand, the effectiveness of China’s rural poverty alleviation programs also suffered from problems of poor governance. Financial resources for such programs are sometimes misallocated due to political motivations of local governments or lobby activities of local powerful people, leading to significant leakages of resources to untargeted interest groups given the weak power of poverty people in local and national political affairs. The active involvement of rural people, particularly the poor, in the socioeconomic development process is still impeded by many institutional barriers. In essence, these problems are rooted in the fact that the government failed in allowing farmers to organize together for protecting their interests. As a result, the rural poor are still unable to advocate their

requirements and to protect their interests with legal means. Such a situation imposes a real risk to China’s long-run success in economic development and poverty alleviation.

Opening domestic market may exposure agricultural sector to risks of external shocks. Although the poverty rural households have no close linkage with commercial market, they are vulnerable to any adverse changes in market conditions. After WTO accession, the Chinese government made effort to establish trade relief measures and social security system in order to prevent the rural poor from harm by undesirable external shocks. Special attention is paid to areas and agro-industries that face the greatest pressure of import competition, such as soybean production in the northeast region.

In summary, China’s past experiences suggest that opening agricultural market for competition is not a

threat to rural poverty alleviation. The outcomes depend very much on how national government deals with the new situation and how the rural poor respond to market signals and policies. To some extent, China’s success can be regarded as clear policy targets, right sequences, coherent policies and complementary institutional changes. Apart from promoting agricultural productivity, increased transfer of rural labor to more productive off-farm activities helps to sustain rural income growth and poverty reduction, which becomes possible due to measures empowering the rural poor. This means that reforms on domestic policies and institutions are needed in order to gain from trade. Therefore, it is critical that rural poverty alleviation programs must pay due attention to improving human capitals of the rural poor and creating appropriate institutions for them to advocate and protect their legal interests so as they become more able to deal with new market conditions.

The WTO multilateral trade system imposes many rules and disciplines on members, which leads to shrunken policy space. However, this change may not impede members to achieve own policy objectives in line with their conditions and priorities. What the member countries should do is to rethink their strategies for rural development. Trade policies should be focused on socioeconomic development, rather than on increasing trade (exports) or ensuring food self-sufficiency.

References

Anderson, K., J. Huang, and E. Ianchovichina, 2002, ‘Long Run Impacts of China’s WTO Accession on Farm-Nonfarm Income Inequality and Rural Poverty’, Conference on China's WTO Accession, Policy Reform and Poverty

Alleviation, Beijing, China, 28-29 June 2002, pp. 28.

Anríquez, G., and K. Stamoulis, 2007, ‘Rural Development and Ppoverty Reduction: Is Agriculture Still the Key?’ Electronic Journal of Agricultural and Development Economics, 4(1), p5-46.

Balat, J., I. Brambilla, and G. Porto, 2008. ‘Realizing the Gains from Trade: Export Crops, Marketing Costs, and Poverty’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4488, Washington, pp. 43.

Bhattasali, D., Li, Shantong and W. Martin (eds.) 2004, ‘China and the WTO: Accession, Policy Reform and Poverty Reduction Strategies’,Oxford University Press and the World Bank,Washington DC.

Brauw, A. D., and J. Giles, 2008, ‘Migrant Labor Markets and the Welfare of Rural Households in the Developing World: Evidence from China’,World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4585, Washington, pp. 60.

Bussolo, M., R. D. Hoyos, and D. Medvedev, 2009,‘Global Income Distribution and Poverty in the Absence of Agricultural Distortions’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4849, pp. 34.

Chen,S.and M.Ravaltion, 2004, ‘Household Welfare Impacts of WTO Accession in China’,Journal World Bank Economic Review, 18(1),pp29-58.

Cheng Guoqiang, 2000, ‘WTO roles in agricultural trade and China’s agricultural development’,China Economic Press, Beijing.

College of Economics and Management, 1999,‘Impacts of China’s Accession to WTO on Agricultural Trade’, The Journal of World Economy, 22(9), p3-16.

Dan Ben-David, Håkan Nordström, and L. Alan Winters, 1999, ‘Trade, Income Disparity and Poverty’ , WTO, Geneva.

Dollar, D. 2008, ‘Lessons from China for Africa’,World Bank Policy Research Working Paper4531, pp33.

Dollar, D. and A. Kraay, 2004, ‘Trade, Growth and Poverty’, The Economic Journal, Vol. 114, pp22-49.

FAO, 2004, ‘Socio-Economic and Policy Implications of the Roles of Agriculture in Developing Countries: Research Programme Summary report’, FAO, Rome.

Ferreira, F. H. G., and M. Ravallion, 2008, ‘Global Poverty and Inequality: A Review of the Evidence’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4623, pp. 44.

Gilbert, John and Thomas Wahl, 2000, ‘Applied General Equilibrium Assessments of Trade Liberalization in China’, memo, Department of Agricultural Economics, Washington State University.

Huang Jikun, 2000, ‘WTO and China’s Agriculture’, in Institute of Agricultural Economics, Annual Report on Economic and Technological Development in Agriculture 2000, pp 17-37, China Agricultural Press, Beijing.

Huang, Jikun, Scott Roselle and M.Chang, 2004, ‘Tracking Distortions in Agriculture: China and Its Accession to the World Trade Organization’, The World Bank Economic Review, 18(1),pp.59-84.

Huang, Jikun, Xu Zhigang, Li Ninghui and Scott Rozelle, 2005, ‘Trade liberalization and China’s Agriculture, Poverty and Equality’, Issues in Agricultural Economy, No. 7, pp.9-15.

Litchfield, J., N. Mcculloch, and L. A. Winters, 2003,‘Agricultural Trade Liberalization and Poverty Dynamics in Three Developing Countries’,American Journal of Agricultural Economics 85(5) , pp 1285-1291.

Liu, X., L. Fang, and H. You, 2007, ‘Agricultural Trade Liberalization and Poverty in China: Linked CGE Model Analysis, International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium, Beijing, July 8-9.

Martin, W. 1999, ‘WTO Accession and China’s Agricultural Trade Policies’, paper presented to the International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium Symposium on China’s Agricultural Trade, San Francisco, June 25-26.

Ministry of Agriculture, 2009a, ‘China Agricultural Statistical Report 2009’, China Agricultural Press, Beijing.

Ministry of Agriculture, 2009b. China Agricultural Trade Development Report 2009’, China Agricultural Press, Beijing.

NBS, (National Bureau of Statistics of China), 2009,‘Poverty Monitoring Report of Rural China 2009’,China Statistics Press, Beijing.

NBS, 2009, ‘China Statistical Yearbook 2009 (and previous issues)’, China Statistics Press,Beijing.

NBS, 2010, ‘Communiqué of China’s National Economic and Social Development in 2010’,released by Xinhuan News Agency on February 25, 2010.

OECD, 2001, ‘ Multifunctionality: Towards an Analytical Framework’, Paris.

Ravallion, M. 2008, ‘Are There Lessons for Africa from China's Success against Poverty?’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4463, pp.28.

Schultz, Theodore W. 1964, ‘Transforming Traditional Agriculture’, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sun Dongsheng, 2001, ‘WTO and China’s Agricultural Trade’, China Agricultural Press,Beijing.

Tian Weiming, 1998, ‘Price Linkages in the Chinese Grain Market’, in Zhou, Z.Y., J. Chudleigh, G.H.

Wan and G. MacAulay ed. ‘Chinese Economy towards the 21st Century, the University of Sydney, pp101-126.

Tian Weiming, 2003, ‘The Socioeconomic Roles of Agriculture in China: National Synthesis Report’,

paper presented to the Roles of Agriculture Project International Conference, October 20-22,Rome.

Wang Zhi, 1997, ‘The Impact of China and Taiwan Joining the World Trade Organization on U.S.and World Agricultural Trade: A Computable General Equilibrium Analysis’, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Technical Bulletin No. 1858.

WTO, 2001, ‘Schedule CLII- People’s Republic of China’, downloaded from http://www.wto.org.

WTO, 2009, ‘International Trade Statistics 2009’,Geneva.

WTO, 2010, ‘World Trade Report 2010 – Trade in Natural Resources’, Geneva.

Wu, Laping, 2000, ‘Research on Integration of Agricultural markets’, China Agricultural Press, Beijing.

Yu, Wen and Huang Jikun, 1998, ‘China’s Reform on Grain Market from the Angle of Rice Market Integration’, Journal of Economic Research, No. 3, pp50-57.

Zhai, Fan and Li Shantong, 2000, ‘The Implications of Accession to WTO on China’s Economy’, Paper presented at the Third Annual Conference on Global Economic Analysis held in Melbourne, Australia June 27-30, 2000.

Zhang, X., and S. Fan, 2004, ‘Public Investment and Regional Inequality in Rural China’, Agricultural Economics, No. 30, pp89-100.

Zhou Z. Y., Wan G. H. and Chen L. B. 1997,‘Integration of Rice Markets: the Case of Northern China’, Asian Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 2, pp158-176.

扫描下载手机客户端