2011.11-Working Paper-Pro-poor Income Distribution Policy in China

1. Foreword

Throughout the world, narrowing the income gap and achieving equitable income distribution and poverty alleviation have comprised major social and economic development goals. One of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals is to halve, between 2009 and 2015, the proportion of the world’s people whose income is less than one dollar a day.1 Over the past two decades, the Chinese government has consistently regarded poverty alleviation as its most important political task, continually strengthening pro-poor policies. In recent years, it has placed increasing emphasis on income distribution. In the 12th Five-Year Plan, the government once again called for the country to "speed up the formation of a reasonable and orderly pattern of income distribution … to reverse the widening income gap as soon as possible." 2 Thus, over the next five years, it will focus on virtually eliminating absolute poverty and narrowing the income gap, objectives which have drawn wide attention in society.

In theory, poverty alleviation and income gap narrowing are complementary to each other. The improvement of the poor’s income will, no doubt, positively impact disparities, especially in the case where the income growth of the poor surpasses the national average. However, we should attempt to determine whether it is equally conducive to

poverty alleviation. If the gap narrows because income growth among the poor exceeds the national average, then it is conducive to poverty alleviation. If, instead, the gap narrows or expands as a result of changes in medium and high-income groups, with no impact on the income growth of the poor, then it is not considered to be conducive

to poverty alleviation. If one of the consequences of a narrowed income gap is a decline in the income of the poor (e.g., the financial crisis), then poverty alleviation will be impeded. The outcome of income distribution, likewise, depends on policy priorities and whether they hinder poverty alleviation. In other words, some income distribution policies are conducive to narrowing the income gap and play a positive role in poverty alleviation (e.g., transfer payments); others, however, may help to narrow the income gap, but either fail to achieve or adversely impact poverty

reduction (e.g., tax increases).

This paper will attempt to summarize China’s recent income distribution policies, evaluate their impact on poverty alleviation and put forward some policy suggestions. It is divided into three parts: the first part will introduce China's income distribution policies, particularly its tax, transfer payment and subsistence allowances policies; the

second part will assess the effects of a few major income distribution policies from the perspective of poverty alleviation, taking into account both empirical results and subjective judgments; the third part will discuss how the income distribution policies can be improved so that they may contribute more significantly to poverty reduction.

2. China’s income distribution policies and their impact on poverty reduction

Under the planned economy, the Chinese government had limited income distribution policy options and the primary means of narrowing income disparities was the implementation of a planned distribution system. As a result of the state’s egalitarian ideology and the ban on private and individual economy in urban areas, the wage

distribution gap within collective economic units was limited to a small range. Up until the late 1970s and the beginning of China’s reform era, income disparities among citizens were very low. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the Gini coefficient for urban areas was about 0.16 (Zhang Dongsheng, 2010). Although

the mechanism of the planned economy was not as strong in rural areas, the political and social unity engendered by the commune system inhibited the growth of income gaps. Except in cases where unequal natural resource distribution led to regional differences, income gaps within communes and production teams were negligible.

In the late 1970s, the Gini coefficient for rural areas was higher than that of urban areas, but even then, it was still quite low, at 0.23 (Zhang Dongsheng, 2010). It should be noted that, while income gaps were small, Chinese society

continued to exhibit large-scale poverty, calling into question the reasonability of the distribution system.

Since the mid-1980s, with the reform of the urban economic structure, rapid development of private and individual economy, and changes in the distribution system, urban income disparities have grown, and in 2008, the Gini coefficient reached 0.37. Similarly, with the privatization of land use rights, the diversification of farmers’ production operations, and the development of rural industries and township enterprises, rural income disparities have also exhibited an upward trend, and in 2008, the Gini coefficient rose to 0.38. Moreover, from 1997 to 2003, the income gap between urban and rural areas increased rapidly (Gustafsson et al, 2008) and has maintained a high level up to the present. In light of such trends, the Chinese government has adjusted the country’s income distribution system, as reflected by the introduction and adjustment of the following policies.

2.1 Personal income tax policy

In the 1980s, the Chinese government introduced a personal income tax. At the Third Session of the Fifth National People’s Congress, on September 10, 1980, the Personal Income Tax Law of the People’s Republic of China was approved, but no specific details were issued and collection did not commence. In September 1986, the State Council issued the Provisional Regulations of the PRC Concerning Personal Income Tax Adjustment, beginning the unified collection of personal income tax. However, as the required threshold was much higher than the average income level of urban residents, only a small proportion of the population contributed and thus, the tax did not play a role in regulating income distribution. Later, with the rapid growth of urban incomes and no adjustments to the threshold, an increasing number people paid personal income tax. As a result, personal income

tax collection rates surpass those of urban incomes, with the total amount collected reaching 394.9 billion yuan in 2009, 8.5 times that in 1999. This personal income tax actually does not play a significant role in adjusting the income distribution of urban residents as it consists of a single tax (a tax on each income) rather than an integrated tax (tax collection based on family income and the population). At the same time, some high-income groups employ a variety of methods to avoid or evade taxes.

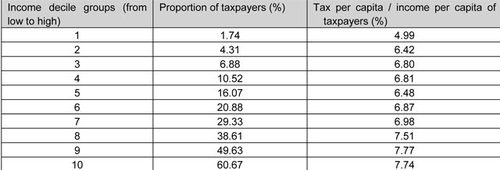

In order to analyze further the effect of personal income taxes on income distribution and clearly demonstrate its positive contribution to narrowing income gaps, we used data for 1270 urban households involved in the 2008 National Bureau of Statistics of China survey to calculate urban tax rates. We found that both the amount of the

personal income taxes paid by urban residents and the tax rate were relatively low. In 2008, the average personal income tax paid by urban residents was 268 yuan, and the average tax rate was less than 1%.3 Meanwhile, we also calculated the personal income tax and tax rate of urban residents in each income decile group, shown in Table 1. It is obvious that the tax rate displays a certain regression. That is to say, the tax rate of high-income groups is higher than that of lowincome groups. This means that, at least by 2008, urban personal income tax played a positive role

in adjusting income distribution, although its role was limited. For example, before tax collection, the income per capita of the highest-income group was 9.48 times that of the lowest-income group, and after the tax collection, this figure dropped to 9.29 times.

Table 1: Personal income tax burden on urban residents in decile groups in 2008

Source: calculation based on 2008 CHIP data

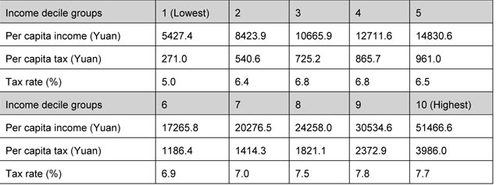

What impact does personal income tax have on poverty? Does it help poverty alleviation or tend to exacerbate poverty? To answer these questions, we calculated the proportion of taxpayers and average tax rate among urban residents in different income groups. Among the lowestincome groups, which account for 20% of the total population, only about 3% paid personal income tax. We can see from Table 2 that the tax rate of the lowest-income taxpayers (10% of the total) was less than 5%. It shows that even if all the personal income tax of these low-income groups

were exempted, there would not be a significant increase in their income. Therefore, the direct impact of personal income tax on urban poverty is quite limited.

Table 2: Proportion of taxpayers and the average tax rate of urban residents in different income groups in 2008

Source: calculation based on 2008 CHIP data

2.2 Social Security Contributions

Although personal income tax does not place a heavy burden on urban residents, workers’ social security payments account for a large proportion of urban household income. For urban workers, social security payments include the following items: pension insurance, medical insurance, unemployment insurance, housing fund, etc. As

the urban social security system does not cover all employment groups, informal sector workers generally do not participate in social security and do not make social security payments. Likewise, different social security programs provide varying forms of coverage for employees.

Table 3 shows the per capita social security payment of urban residents in decile groups and its proportion in per capita income. It can be seen that, in general, the per capita social security payment of high-income households is higher than that of low-income households and the proportion of the payment in income of the former is also higher than that of the latter. However, the payment rate of high-income group residents is not so different from that of low-income groups. We calculated the Gini coefficient of residents’income gap before and after social security payments and found the figure was 0.3492 and 0.3489, respectively. Therefore, although social security payments help narrow the income gap, their role is very limited.

Then, how do social security payments impact urban poverty? From Table 3, it is evident that if the social security payments of the lowest-income groups (20% of the total) are exempted, their disposable income per capita will rise by 5-7%. Disregarding the benefits of social security for urban residents and using the 2008 average urban minimum living standard as the poverty line, the incidence of urban poverty after social security payments is 0.8. Thus, even in the case where all social security payments of low-income residents are exempted, the growth in poverty incidence will not exceed one percentage point.

Table 3: Burden of social security payments on urban residents in income decile groups in 2008

Source: calculation based on 2008 CHIP data

2.3 Agricultural and rural tax

Under the planned economy, the income of urban residents was higher than that of rural residents, and while the former were not subject to personal income tax, the latter were required to pay agricultural tax and other taxes.4 The taxes paid by farmers included taxes on agricultural products, specialty products, slaughter animals and deeds, known as the "Four Agricultural Taxes." In addition, farmers had to pay a variety of other official taxes, summed up as

the "Three Retained Fees and Five Overall Planned Fees." In many places, these miscellaneous taxes were much higher than the agricultural tax. Farmers were also required to pay other fees in all kinds of names. In the 1990s, the tax burden on Chinese farmers reached a particularly high level, resulting in public resentment and complaints. In response, the central government issued repeated orders and various documents to curb this type of behavior by some local governments. However, as the fundamental financial relationship between the central and local governments remained unchanged, the binding provisions did not solve the problem.

In accordance with the provisions of the central government, the amount of the "Three Retained Fees and Five Overall Planned Fees" should not have exceeded 5% of the net income of local farmers in the previous year. Seen from survey data, however, this amount was much higher than the standard in many places. A research team at the Development Research Center of the State Council recently carried out a special investigation on "County Finance and Income Growth of Farmers," examining farmers’tax burdens in three agricultural counties. The team found that the per capita tax on farmers in these three counties in 1997 was 12%, and this ratio even reached 28% in one county where rural residents had the heaviest tax burden.5

To alleviate the growing burden on farmers, the central government finally made a determined effort to solve the fundamental problem. Beginning in 2006, it removed the agricultural tax nationwide and prohibited local governments from collecting the so-called "Three Retained Fees and Five Overall Planned Fees." The 2007 household survey data shows that the tax burden on farmers has since become negligible.

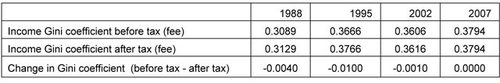

Table 4 shows the changes in tax burden on rural households in the two decades from 1988 to 2007.The average tax burden in 1988 was 5% and reached 5.3% in 1995. In 2000, pilot reform on agricultural tax was launched and the tax burden in some places began to decline, dropping to 2.8% in 2002. In 2007, after the agricultural tax was

exempted nationwide, the average tax burden on farmers dropped to 0.3%. Such a process of change reflects the general situation of rural tax burdens during this period.

Table 4 also shows the tax burdens of highincome rural households and low-income groups. It should be said that these results are more interesting. It is obvious that in 1988, 1995 and 2002, the average tax (rate) burden on lowincome households was significantly more (higher) than that of high-income households. The tax rate on the lowest-income households (10% of the total) nearly doubled that on the highest-income households (10% of the total) in 1988 and, in 1995, the former was four times the latter. Although the average household tax (fee) rate decreased in 2002, the difference between the tax (fee) rates of low-income groups and high-income groups did

not fundamentally change.

From the perspective of income distribution, rural tax policy shows a strong regression and is not conducive to narrowing the income gap. Instead, it leads to growing income disparities. First, it expands the income gap within rural areas. The results in Table 5 show that the Gini coefficient of income inequality after tax is higher than the Gini coefficient before tax, which was particularly evident in 1995. Second, it expands the income gap between urban and rural residents. In 1995, for example, the rural-urban income gap was 2.47 times. After the removal of the agricultural tax, the rural-urban income gap drops to 2.34 times.6

Table 4: Average tax (fee) rate on China's rural residents of different income groups from 1988 to 2007

Source: Calculation based on 1988, 1995, 2002 and 2007 CHIP data

Table 5: Changes in rural income gaps before tax (fee) and after tax (fee), 1988-2007

Source: 1988, 1995 and 2002 figures are from Sato Hiroshi (2006) and 2007 figures are calculated by the author based on CHIP data.

Not only rich farmers, but also poor farmers were required to pay taxes, which made the poor become poorer, negatively affecting rural poverty. This trend is mainly reflected by the increasing rural poverty incidence and the

declining living standards of poor people. Based on 1995 figures, we attempted to simulate how rural poverty would have been impacted if all taxes and fees were cut. The results show that, according to the official poverty line, in 1995, the actual poverty incidence in rural areas was 7.4%; if all taxes and fees were exempted, the poverty incidence would drop to 3.9%. In other words, after all the taxes and fees were exempted, the population of rural poor would have been reduced by 47% while the poverty gap would have declined by 44%. Thus, the longstanding rural tax policy was an important policy factor in the expansion of rural poverty. At the same time, however, it demonstrates that, after 2006, the rural tax reduction policy neither narrows the income gap nor contributes to poverty alleviation. It is disappointing that such policy can only bring about a one-time poverty reduction effect. In order to achieve a more lasting impact, a “negative tax” policy needs to be issued for the poor, that is, a transfer payment policy, which will be discussed in the next section.

2.4 Minimum living security system: the urban experience

The urban minimum living security system was established in 1993 in Shanghai, a pilot area. In 1999, the State Council promulgated the "Regulations on the Minimum Living Guarantee for Urban Residents" and the system was

expanded to include a larger number of areas nationwide. Since 2001, the number of beneficiaries under the minimum living security system has increased rapidly. At the end of June 2002, the Ministry of Civil Affairs announced that the initial goal had been achieved, "guaranteeing all those who should be guaranteed." According to the 2010 Social Service Development Statistical Report released by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, by the end of 2010, a total of 11.45 million households and 23.105 million urban residents received subsistence allowances.7 The annual

expenditure of the government on urban subsistence allowances was 52.47 billion yuan, an increase of 8.8% over the previous year. The central government contributed 36.56 billion yuan in subsidies, or 69.7% of the total capital

expenditure. The majority of people who received the subsistence allowances included unemployed persons, elderly without pensions and minors. These three groups accounted for more than 70% of the total people receiving subsistence allowances.8 In 2010, the average urban subsistence allowance nationwide was 251.2 yuan, up 10.3% over the previous year; and the monthly subsistence allowance for urban residents was 189.0 yuan, up 9.9% over the

previous year.

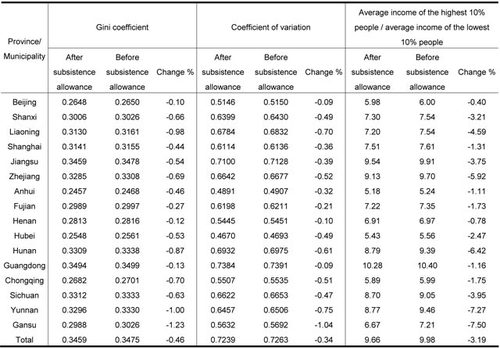

Then, to what extent does the urban minimum living security system help reduce the income gap of urban residents? To estimate the effect of subsistence allowances on the overall income gap, some of the commonly-used indexes of income inequality were calculated based on CHIP 2007 urban household survey data, including personal

income Gini coefficient, coefficient of variation, the ratio of the average income of the highest 10% people and the average income of the lowest 10% people, and the changes before and after the delivery of subsistence allowances. We can see from Table 6 that the Gini coefficient of per capita income of all surveyed urban residents before and

after the delivery of subsistence allowances was 0.3475 and 0.3459, respectively, with a decline of only 0.46%. These figures demonstrate that the delivery of subsistence allowance policy plays a limited role in reducing income inequality.

Table 6: Personal income inequality indexes of all samples: level and change

Note: Change %=((gap after subsistence allowance - pre-subsistence allowance gap)/pre-subsistence allowance gap)×100, the same below

Source: Li Shi, Yang Sui, 2009

Although the urban minimum living security system does not have a significant impact on the income gap, it has an obvious effect on poverty alleviation. If the local minimum living standard is taken as the poverty line, then, based on CHIP 2007 urban household survey data, we can work out the changes in poverty incidence, poverty gap and weighted poverty gap before and after the subsistence allowances. The results show that the poverty incidence declined by 42% on the whole. More importantly, the decrease rate of the poverty gap and weighted poverty gap was even higher, respectively reaching 57% and 63% (Li Shi, Yang Sui, 2009). This means that the subsistence

allowance has not only lifted a considerable number of people out of poverty, but also brought their income above the poverty line. Even for those who have not shaken off poverty, their living standards have been improved and level of

poverty reduced.

Thus, the urban minimum living security system not only comprises a government income transfer policy, but also serves as a policy for income redistribution. If just viewed from the perspective of narrowing income disparities, its impact on income distribution is very limited. From the perspective of poverty alleviation, however, its role is obvious. We can say that it is an effective policy for pro-poor income distribution.

2.5 Minimum living security system: the rural experience

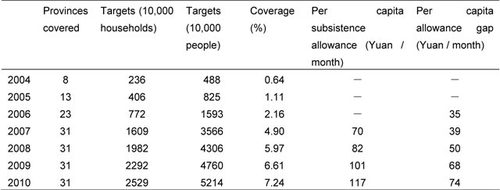

The rural minimum living security system was established a few years after its urban counterpart and was not promoted nationwide until 2007. Table 7 shows that, in 2004, the rural minimum living security system was only

set up in eight provinces and the number of the people receiving the related security was less than 5 million. In subsequent years, more and more provinces issued the rural minimum living security policy, covering a larger

proportion of people. For example, in 2010, 46% of the rural residents received coverage and per capita subsistence allowances increased 67% over 2007 levels. Taking into account the rural rate of inflation, the actual growth rate was

more than 55%. Moreover, the per capita subsistence allowance income of recipient households also nearly doubled.

Table 7: Development of rural minimum living security system

Source: Civil Affairs Development Statistics Report over the years http://www.mca.gov.cn/article/zwgk/tjsj/

While the coverage of the rural minimum living security system has expanded rapidly, it still remains relatively low and thus, has little impact on narrowing rural income gaps. This situation is identical to the effect of the urban

minimum living security system. So, what role does it play in rural poverty alleviation? Table 8 shows the change in the FGT index before and after the subsistence allowance for the secured and unsecured groups, based on 2008 rural poverty monitoring survey data. In 2008, among the key counties for poverty alleviation, 3,835 households and 16,636 people were covered by the minimum living security system. The coverage of the minimum living security

system in key counties was 7.28%, which is above the national average. As shown in Table 8, for the secured groups, when the poverty line is 1196 yuan (official poverty line set in 2009), the subsistence allowance has reduced their poverty incidence by 21%, poverty gap by 32.6% and weighted poverty gap by 37.5%. This indicates that the rural minimum living security system lifted more than 20% of the secured out of poverty and greatly improved the poverty

status of those still in poverty.

Table 8: Poverty status of the secured and unsecured: FGT index

Note: Figures in Line 3: Line 1 minus Line 2, divide line 1 and then multiplied by 100 Similarly for figures in Line 7

Source: Deng Quheng, Li Shi (2010)

However, for all population groups in poor areas, the pro-poor effect of the minimum living security system is not obvious. As shown in Table 8, the system causes the incidence of poverty in poor areas to decline by less than 3%

and poverty gap to decline by less than 4%. This result is somewhat puzzling. According to the published data of the Ministry of Civil Affairs, 5% of rural residents receive subsistence allowances. If most of these people are impoverished, then the pro-poor effect of subsistence allowances should be very obvious, just like the situation we analyzed above. How can we explain these puzzling results? One explanation is that the target rate of the rural

minimum living security system is relatively low. According to the 2008 poverty monitoring data, the targeting error is higher than that of the urban minimum living security system, and most of the people involved in the error are those

who do not meet the requisite conditions to receive subsistence allowances. As their income before the subsistence allowance is already higher than the poverty line, the subsistence allowance income, of course, exhibits no pro-poor effect. Another explanation is that rural household survey data or poverty monitoring data cannot accurately represent the poor, the primary targets of the minimum living security system. Based on poverty monitoring data, in 2008, only 7.8% of the poor areas (counties) received subsistence allowances. The actual proportion, though, might be higher, and if these missed targets had also been taken into account, the pro-poor effect of the rural minimum living security system might have been more obvious.

2.6 Preferential agricultural policies in rural areas

Since the beginning of the new century, in order to better implement the strategy of balanced development, the Chinese government issued a series of preferential agricultural policy measures. These policies can be divided into two categories according to the manner in which they benefit farmers. The first category includes subsidy policies aimed at increasing farmers’ income directly, such as grain subsidies, improved varieties subsidy, farm machinery purchase subsidies, etc.; the second category consists of public service policies aimed at establishing farmers’ social security networks, such as the new cooperative medical system, "two exemptions and one subsidy" policy for education, rural minimum living security policy, etc. Needless to say, these preferential agricultural policies played a certain role in increasing farmers’ income and inhibiting the expansion of the rural-urban income gap. More importantly, these preferential agricultural policies also played a positive role in narrowing the income gap within rural areas and alleviating rural poverty. For some time, agricultural prices in China have been low. Similarly, the

decentralization of land management, low scale of production, and low agricultural yields have resulted in limited incomes from agricultural production and management. That is to say, farmers engaged in agricultural production,

especially grain production, tend to be low-income or poverty-stricken people. Some relevant research shows that farmers experience more equal income distribution from agriculture, which, to some extent, has an inhibitory effect on the expansion of the income gap in rural areas (Khan and Riskin, 1998). Thus, agricultural subsidies, including food and price subsidies, would benefit those households engaged in agricultural production and management, allowing their incomes to increase at a higher rate, narrowing the income gap within rural areas and reducing their risk of falling into poverty.

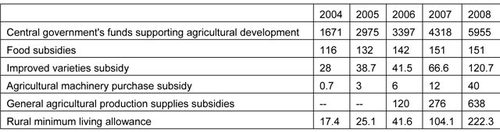

In order to implement preferential agricultural policies, the central government has consistently increased its financial contribution. Table 9 shows that, from 2004 to 2008, central government funds for supporting agriculture rose from 167.1 billion yuan to 595.5 billion yuan, an increase of 3.56 times and an annual growth rate of 61%. During these four years, food subsidies increased by 30% and seed subsidies multiplied 4.3 times, while the

growth rates of agricultural production machinery purchase subsidies and general agricultural production supplies subsidies were even higher.

It is also worth discussing here the compensation policy issued in 1999 for returning farmland to forests. The pilot projects of returning farmland to forests were first constructed in Shaanxi, Gansu and Sichuan province. In 2000, the project implementation area was expanded to include the upper reaches of Yangtze River in the west (i.e., Yunnan, Sichuan, Guizhou, Chongqing and Hubei) and 174 counties in 13 provinces in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River (i.e., Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Henan and Xinjiang). In 2002, the project of returning farmland to forests was implemented comprehensively across China and the coverage

extended from 20 western provinces and autonomous regions to 1897 counties in 25 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities. With the gradual increase in the compensation standards, this policy has been widely welcomed by local farmers. Given the geographical distribution of the project, recipient farmers all live in mountainous and ethnic minority areas with income levels far below the national average. The compensation policy for returning farmland to forests has increased their income to some extent and narrowed the income gap within rural areas and between regions. Meanwhile, the direct subsidies for converting farmland to forests will help to diminish the incidence of poverty in these regions and increase income generation opportunities. People at the edge of poverty are usually strongly risk averse and thus, often reluctant to work outside the home. For the poor, the subsidy for returning farmland to forests represents a kind of risk fund to a certain degree,increasing the likelihood of their seeking off-farm employment and promoting poverty alleviation in these project areas to some extent.

Table 9: Central government transfer payments for the rural subsidy policies (Unit: 100 million yuan)

Source: Li Xiaoyun, et al. (2010)

To monitor poverty, the National Bureau of Statistics conducted surveys on whether the sample households in poverty-stricken counties received food subsidies and if so, how many subsidies they received. According to the survey data, in poverty-stricken counties, the proportion of subsidies for the non-poor is higher than that of poor households. In 2007, for example, 51.73% of the rural households received food subsidies (direct grain subsidy, improved variety subsidy and general subsidies for agricultural production supplies), covering 39.4% of the low-income households and 37.7% of the poor households. In 2008, the proportion of the rural households receiving direct grain subsidies increased significantly, up to 72.57%, covering 63.07% of the low-income and poor households (Li Xiaoyun, et al. 2010).

Table 10: Proportions of the poor and the non-poor receiving policy subsidies in key counties for poverty alleviation

Source: Li Xiaoyun, et al (2010), calculation based on poverty monitoring sample survey data of National Bureau of Statistics

It should be noted that these preferential agricultural policies are reflected in the farmers’income composition to some extent. Table 11 shows, in the period from 2005 to 2008, the proportion of transfer income in the net income of rural households in poverty-stricken counties grew by 50%, and the growth rate of this proportion of poor households was even higher, exceeding 66%. Moreover, the proportion of transfer income in the net income of poor households was actually higher than that of the non-poor. For example, in 2008, the former was 30% higher than the latter. The main factors promoting the rapid growth of rural households’ transfer income are the government’s preferential agricultural policies, especially those including subsidies and cash transfers (e.g., food subsidies and subsistence allowances).

As it is very difficult to gather subsidy information in household surveys, it is unrealistic to make quantitative estimates of the income distribution effect and pro-poor effect of various subsidies. Here, we can only offer some basic assessments of the two effects using the aforementioned limited information. First, these preferential agricultural policies, most likely, helped to either narrow the income gap or prevent its widening within rural areas. Based on macroeconomic data from the past decade, the income gap within rural China has been gradually expanding, and the rural Gini coefficient rose from 0.35 to 0.38 between 2000 and 2008 (Zhang Dongsheng, 2010). The expansion speed of the income gap within rural areas during this period was obviously lower than that of the previous decade.9 Although many factors contributed to the slowing of income gap growth rates within rural areas, the Chinese government’s preferential agricultural policy, no doubt, comprised a key measure.

Table 11: Proportion of transfer income in the net income of rural households in poverty-stricken counties from 2005 to 2008

Source: Poverty Monitoring Report of National Bureau of Statistics

Secondly, these preferential agricultural policies help alleviate poverty because they specifically target low-income and poor people, such as the minimum living security policy previously mentioned, the food subsidies discussed here and the compensation policy for returning farmland to forests. Different data show that the reduction of poverty in rural China has been significant over the past decade. Similarly, a variety of factors have led to a substantial reduction in poor people, but the role of the preferential agricultural policies cannot be ignored.10 Finally, of course, the goal of preferential agricultural policies is not entirely to alleviate poverty. From this perspective, therefore, these policies have many shortcomings. If we appropriately adjust these policies to make them

more effective in poverty alleviation, and increase the degree of targeting, these policies will have a better pro-poor effect (China Development Research Foundation, 2007).

2.7 GSP social security

Over the past few years, China has carried out social security system reform with the aim of providing coverage for all Chinese people. The government is expanding the social security system to include the urban informal sector and migrant workers, a very praiseworthy endeavor. The income distribution and poverty reduction effects of China's social security system reform are also worthy of attention and study, but some research difficulties exist. A component of public policy, social security is, to a great extent, only reflected in government or personal expenses

rather than in individual or household income. Yet, the measurement of income distribution and poverty both use income as their basic indicator. For example, the amount of money people with health insurance save on medical expenses does not affect their income. Therefore, if income is taken as the indicator to measure poverty, then the possession of medical insurance will not appear to impact a person’s poverty status.

However, if we expand the concept of income to mean the wellbeing of an individual or a family, then all social security projects that help increase wellbeing can be regarded as income. In other words, when household disposable income is the same, the actual income (income measured by wellbeing) of families secured under the social security system will be higher than that of unsecured families. Moreover, we can further estimate the market value of social security for each family and use it to measure actual household income. By comparing actual income

and the disposable income of families in the traditional sense, we can see the impact of social security on income distribution and poverty alleviation. Based on 2002 CHIP data, Li Shi and Luo Chuliang (2006) estimated the income

distribution effect of differences in social security and public services for urban and rural residents. The results show, for that year, the market value of social security and public services received by urban residents was 17 times that of rural residents. This caused the income gap between urban and rural areas (per capita income of urban residents/per capita income of rural residents) to increase from 3.1 to 4.4 times and the Gini coefficient of the national income gap to grow from 0.46 to 0.51.

Due to the expansion of social security in recent years, rural residents and employees in urban informal sectors, especially migrant workers, have also been included within the scope of the system. It has, to some extent, adjusted distribution relations and helped to narrow income gaps. As there are not so many studies in this area, we have no idea to what extent it has diminished rural-urban income disparities, to what extent it has narrowed the income gap within urban areas and within rural areas, and to what extent it has narrowed the income gap nationwide. However,

one thing is clear: establishing a social security system with complete coverage and reducing social security disparities among different groups will play a positive role in narrowing income gaps and achieving social equity.

Similarly with income distribution, it is also difficult to estimate the impact of social security on poverty alleviation. As mentioned above, whether people enjoy social security is not reflected in changes in personal or household disposable income and these same indicators are usually used to measure the scale and degree of poverty. A

similar problem arises if we use consumer spending to measure poverty. For example, families with medical insurance will increase spending on health insurance premiums but reduce medical expenses. If the reduction in

medical costs leads to a decline in household expenditures (assuming medical expenses are also part of consumer spending), then it might seem the family now qualifies as poor, having fallen below the poverty line after the deduction of consumer spending. Thus, the anti-poverty effect of social security must be analyzed from different

angles. Let us take medical insurance as an example. For any family, health insurance means an increase in its wellbeing, especially in the context of government subsidies for medical insurance. With disposable income and the

poverty line remaining the same, an increase in welfare means a decline in the poverty level. In this sense, social security helps to alleviate poverty. The extent to which it alleviates poverty, however, depends on institutional arrangements and the expenditure sharing of social security items.

For China, the progress achieved in rural social security is worth mentioning. The new rural cooperative medical system now covers the entire rural population. By the end of 2008, it covered all counties (including municipalities and autonomous regions) with rural populations and a total of 815 million farmers participated in the system,

accounting for 91.5% of the total rural population. In total, 1.5 billion people nationwide have received compensation amounting to 125.3 billion yuan.11 Besides, in the last two years, the government has continued to raise its financial

contribution and proportion of reimbursed medical expenses, increasing benefits to farmers. This is crucial for rural poverty alleviation, especially in the case of disease-related poverty. For the moment, we cannot measure the pro-poor effect of the new rural endowment insurance system, as the pilot projects were only just implemented in

2010. In the next four years, after it is widely promoted in rural areas nationwide, it will play an important role in reducing poverty, especially among rural elderly. Because these social security projects are supported by government funds, they can be called income redistribution policies to a large extent. Considering their anti-poverty

characteristics, they can also be called pro-poor income distribution policies.

3. The direction of reform in China's income distribution policy

China's income distribution and redistribution policies still need to be improved. First of all, the policy system is not comprehensive; second, there is no coordination between various policies; third, the policies have no clear anti-poverty goal. In response to these problems, we put forward the following five suggestions on the direction income

distribution policy reform should take, emphasizing the need for an anti-poverty objective.

First, we need to make two major adjustments to China's tax revenue system to enhance its function as a mechanism for reducing poverty and redistributing income. On the one hand, we need to gradually reduce indirect taxes and increase direct taxes. Tax theory tells us that indirect taxes utilize the same rate across different income

groups. In other words, people who spend more, pay more taxes, including the poor, who share the same tax rate with the rich. Direct tax, however, is based on personal and business income, and progressive tax rates can be determined according to income level, strengthening its role in income distribution. Reduction of indirect taxes may, to some extent, help enhance the wage level and afford the low-wage population rapid growth in wages, thus alleviating poverty. On the other hand, we should convert personal income tax from the current itemized tax to a general tax. The former entails taxation on each income while the latter is a general tax on family income. The

implementation of general tax can avoid the exemption of tax payment of low-income groups and poor people and might help in narrowing the income gap of personal income tax.

Second, China's income distribution policy does not involve a large number of government transfer payment projects. The existing transfer payment projects, such as urban and rural minimum living security systems and social relief projects, also exhibit low levels of coverage. Government should classify various vulnerable groups, especially

people without the ability to work, and develop related transfer payment projects based on the characteristics of various vulnerable groups. Apart from a minimum living security for low-income people, we also need to develop targeted transfer payment projects for the disabled, orphans, AIDS patients, children and the elderly from low-income

families, single parent families and other vulnerable groups. The experience of some countries shows that the child allowance is an effective policy to alleviate child poverty and prevent child malnutrition. For China, the implementation of a nationwide system of child allowances is unrealistic, particularly in rural areas or rural poor regions. Nevertheless, we can provide child allowances to urban low-income families. Old-age subsidies offer an additional

form of income transfer payments. China's longestablished social pension insurance is linked with formal sector employment, which means that a large portion of the population is not covered by social pension insurance, including the elderly in rural areas, urban elderly without employment experience and retired people from the informal

sector. For these people, old-age subsidies are necessary and can help to alleviate poverty, as they are usually the people most vulnerable to poverty.

Third, providing complete coverage under the social security system and equal access to public services will not only help regulate the distribution of income, but also help alleviate poverty. The direction of this reform should be maintained. In the reform process, we must ensure poor people enjoy social security benefits as well as guarantee

that they pay minimal fees or none at all. For example, in the last two years, the government has been consistently increasing its investment in the new rural cooperative medical system (NCMS). The farmers’ reimbursement rate, however, is only 50 percent or so, and even lower in many places. For some low-income families, the burden of these medical costs is still too high, and as a result some poor people do not see a doctor when they

are ill. In this case, we should determine reimbursement rates according to income level. Farmers with lower incomes should enjoy higher reimbursement rates. In such a way, the new rural cooperative medical system can achieve a more significant pro-poor effect. The pension subsidy policy implemented in some places exhibits similar

problems. In issuing pension subsidies, the income status of families is not taken into account and the same standard is used across all recipient groups. Therefore, in the future development of an old-age subsidy policy, we should consider household income of the elderly and develop different subsidy standards to enhance the pension subsidy’s pro-poor effect.

Fourth, China's preferential agricultural policy will continue to play a positive role in narrowing the rural-urban income gap and alleviating rural poverty. Meanwhile, in the implementation process, the policy needs to be continuously improved. One important improvement involves strengthening its role in poverty reduction. At the

moment, food subsidies use a relatively uniform national standard for both developed and povertystricken regions. If we were to use different standards, though, we could enhance the food subsidy standard for less-developed areas,

especially those that are impoverished, in order to provide more benefits to low-income rural residents and farmers engaged in agricultural production. It should be said that it is feasible to develop different food subsidies for a diversity of regions and income groups with minimal side effects. Moreover, the role of this policy in reducing poverty will be enhanced significantly. With other agricultural subsidies, we should likewise develop different subsidy standards.

Fifth, while striving to equalize public services, we should consider giving more compensation to poverty-stricken areas and poor people. Equal access to public services attempts to correct longstanding discriminatory public policies. However, as these discriminatory policies have long-term effects, some people, such as farmers and ruralmigrants, lag far behind the national average in human capital and wealth accumulation. Even if we achieve the goal of providing equal access to public services, it is difficult for these people to catch up with those who have long been enjoying public service benefits. Thus, at the beginning stage of policy change, it is completely necessary

for public services to give priority to these people. Only in such a way, can we eliminate the differences in development opportunities for different groups and lift vulnerable people out of poverty in the shortest time possible. In this regard, one of the most prominent examples is the provision of basic education in less-developed

areas. Although the nine-year compulsory education policy has been implemented universally in rural areas now, the quality of education is worrying. If we cannot fundamentally solve the problem of low quality compulsory

education in rural areas, poverty in China will continue to exist and will “transfer” from rural areas to the cities with the migration of rural residents. To improve the quality of compulsory education in rural areas and diminish discrepancies with the quality of urban education, substantial government support and investment are needed. Meanwhile, high-quality educational resources should be transferred to rural areas, less-developed regions and poverty-stricken areas.

In short, China is facing many social problems, of which the widening income gap is particularly noteworthy. The Chinese government needs to establish a comprehensive income distribution system to meet this challenge. Throughout this process, the most important objective should be achieving maximum poverty alleviation.

References:

Chen Xiwen (2003), "Research on China's County Finance and Income Growth of Farmers", Taiyuan, Shanxi Economic Press.

China Development Research Foundation (2007), "China Development Report 2007: Poverty Eradication in the Development", China Development Press.

Deng Quheng, Li Shi (2010), "Assessment of the rural social security progress and its poverty reduction effect: based on the case of the minimum living security system", a background report prepared for the Evaluation Report of the Implementation Effect of "China's Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development Outline (2001-2010)"

Distribution and Growth of Household Income, 1988 to 1995" (with A.R. Khan), China Quarterly, 154, June 1998.

Gustafsson, Bjorn, Li Shi, Terry Sicular (2008), Income Inequality and Public Policy in China, Cambridge University Press, April 2008.

Khan, Aziz and Carl Riskin (1998), "Income and Inequality in China: Composition, National Bureau of Statistics (2009), "China Rural Poverty Monitoring Report 2009", China Statistics Press.

Li Shi (editor in chief) (2010), Evaluation Report of the Implementation Effect of "China's Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development Outline (2001-2010)".

Li Shi, Luo Chuliang (2007), "A Reassessment of China's Urban-rural Income Gap", "Journal of Peking University", 2007, No. 2.

Li Shi, Yang Sui (2009), "Effect of China's urban minimum living security system on income distribution and poverty", China Population Science, 2009, No. 5.

Li Xiaoyun, Zhang Keyun, Tang Lixia (2010), "Assessment of General Preferential Agricultural Policy and Its Poverty Reduction Effect", a background report prepared for the Evaluation Report of the Implementation Effect of "China's Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development Outline (2001-2010)".

Sato Hiroshi, Li Shi, Yue Ximing (2006), "Effect of Redistribution of Rural Taxation in China", "Economic Journal," August 2006.

Wu Guobao, Guan Bing, Tan Qingxiang (2008), "Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Pro-poor Effect of National Food Subsidy Policy in Poverty-stricken Areas", "China Rural Poverty Monitoring Report 2008", National Statistics Press.

Zhang Dongsheng, editor in chief (2010): "Annual Report on China’s Distribution of Income for Residents", Economic Science Press.

扫描下载手机客户端

地址:北京朝阳区太阳宫北街1号 邮编100028 电话:+86-10-84419655 传真:+86-10-84419658(电子地图)

版权所有©中国国际扶贫中心 未经许可不得复制 京ICP备2020039194号-2