2011.01-Working Paper-Agriculture, Food Security and Rural Development A Synthesis

Agriculture, Food Security and Rural Development: A Synthesis

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

1.Introduction: Divergent Performances

2.Agriculture in China’s growth and poverty reduction

a.Agriculture as the priority for overall development

b.Rural development and poverty reduction

c.Key elements in China’s agriculture and rural development

d.Lessons that are most relevant to Africa

3.Agriculture and rural development partnership in Africa

a.What strategies are being implemented

b.China’s engagement and approaches in Africa

c.Perspectives from Africans

d.Approaches by established Donors

4.Going Forward: Opportunities and Challenges

Box 1.Foreign Aid in China’s Agriculture: Volume and distribution

Box 2.China’s Development Cooperation: Experiences and Lessons

Annex 1

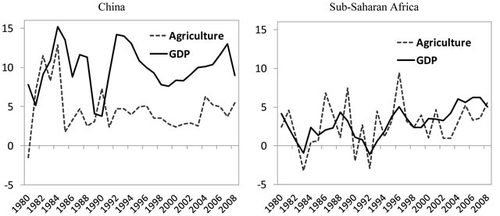

Figure 1.Annual GDP and agricultural GDP growth, Africa and China

Figure 2.China has been following its Comparative Advantage at various stages

Figure 3.Poverty Alleviation funds from the Central Government Sources

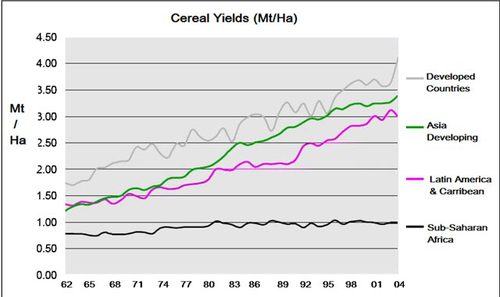

Figure 4.Average Cereal Yields (Mt/ha)

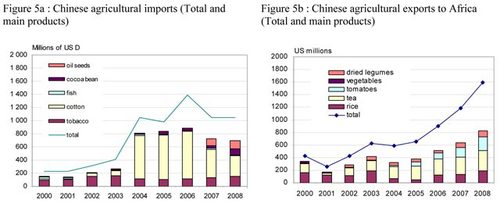

Figure 5.Chinese Agricultural export to and import from Africa

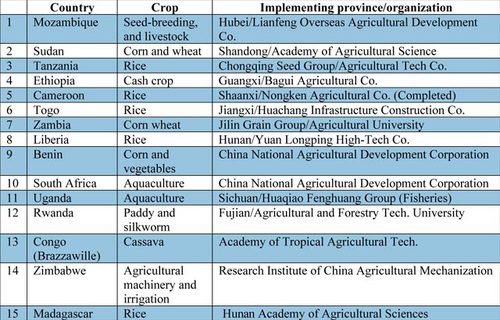

Table 1.Fifteen Agricultural Technology Demonstration Centers in Africa, 2006-2009

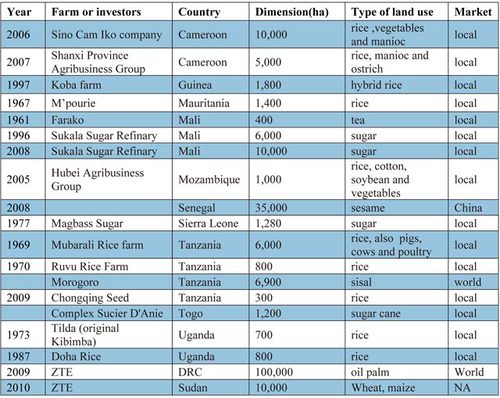

Table 2.Chinese investment in Agriculture in African Countries

Executive Summary

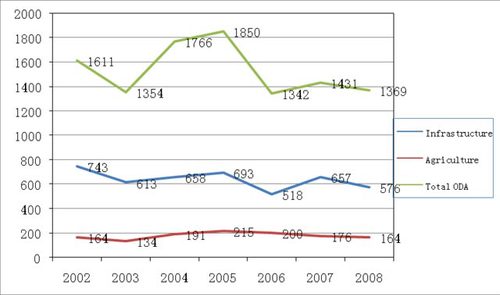

The multiple crises of food, climate change, and finance that have been recently confronting the world have highlighted the crucial importance of agriculture for developing countries. During the past two decades there was inadequate attention and investment in rural development and agriculture by the international donor community, with only 4% of total ODA directed to the agricultural sector in 2008 as compared with 14% in 1980.

China’s experience in development shows that effective policies and strategies targeted at the agricultural sector and rural development can greatly assist poverty reduction efforts. In this context, the second event of the China-DAC Study Group on ‘Agriculture, Food Security, and Rural Development for Growth and Poverty Reduction’ addressed

three core issues: (i) the key elements of China’s success in agricultural growth, food security and rural development, and to what extent these experiences and lessons are relevant to Africa; (ii) the experience of African countries in these areas, and the approaches of different development partners; and (iii) the future implications and opportunities for all stakeholders to work together more effectively to improve agriculture and rural development in Africa.

Recognizing that agriculture is a powerful engine of growth, the Chinese government initiated a major shift in development strategies in the post-1978 reform period, establishing agriculture as the priority of economic development. Agricultural growth and rural diversification was driven by home-grown institutions such as the household responsibility system (HRS), and township and village enterprises (TVEs); and the ‘organic combination’ of three forces, the state, the market and farmers, and involved a strategy that can be best summarized as “first relying on government policies and second on science and technology”.

Although China’s experience and situation may not be directly replicable in Africa, some aspects are relevant and useful. In particular, first, even though the main drivers of economic growth may lie in laborintensive manufacturing sectors, agriculture is fundamental to broadbased and pro-poor growth and should thus be given priority. Second, China’s approach also facilitates experimentation at the smallholder level, encouraging a process of self-discovery and self-development. Third, African countries can also draw lessons from some of the problems that currently exist in China’s agricultural sector, such as widening rural-urban income disparities, structural inequalities, and issues regarding land-use rights, environmental pollution and ecological degradation.

In Africa, despite a recent acceleration in agricultural growth, a number of significant challenges are facing the agricultural sector. There is an urgent need to address the under-capitalization, low productivity, and competitiveness of the sector, improve the connection between input and product markets, and develop intra-regional trade. After realizing that private sector-led agricultural development was not sufficient to generate growth, international development partners are embracing several innovative approaches to assist agricultural development in African countries. The Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Program (CAADP) is also considered a promising continental-wide framework.

Although China has identified the agricultural sector as an important area for trade and assistance to Africa, there are concerns that Sino-Africa trade patterns have not directly benefited African agricultural and rural development. Based on re-thinking the past experiences, China’s approach to agricultural development assistance is making a transition to a model that will be led by (public or private) enterprises and facilitated by the government through R&D and technological demonstration centers. This could be considered an innovative mechanism for supporting self-discovery in these sectors. Participants in the event felt that there is a real scope for mutual learning especially as it relates to smallholder development, food security, intensification, and adapting market mechanisms to support agriculture.

A number of key challenges and opportunities have been identified for future engagement and the development of the agricultural sector in Africa. In recent years, established donors have made efforts to harmonize their aid through greater transparency, better information sharing and increased coordination, and African countries have started to

take leadership in developing and managing their rural development strategies.

It is hoped that all development partners, including China, will support CAADP. The common objective is to ensure that China’s agricultural involvement in Africa takes place within a policy framework that maximizes a long-term ‘win-win’ approach including technology transfer, infrastructure investment, and increased food security and

sustainability for both parties. Participants have indicated that China’s agricultural cooperation, if fine-tuned, could bring tremendous benefits. China’s approach at home of learning from experiments and facilitating self-discovery may have valuable lessons for all.

All stakeholders, Africans, Chinese and established donors, are facing huge challenges. It is thus in everyone’s interest to improve the effectiveness of aid and avoid repeating past mistakes. The key message is therefore to join hands in a long journey of discovery together with all the stakeholders, and scale up in some cases of success, in a concerted effort to help African countries improve their food security and agricultural and rural development to reduce poverty and improve the lives of all of their citizens.

1.Introduction: Divergent Performances

Africa’s 53 countries and China are vastly diverse in terms of their natural endowments, and demographic, geographic, socio-economic,ethnic, political, historical and cultural conditions. They also exhibit divergent patterns in agricultural growth, food security, and poverty reduction. Starting from a GDP level slightly lower than that of Sub-

Saharan Africa, China’s economic output surpassed output in Africa in1983, and ten years later, in 1993, its GDP per capita surpassed African GDP per capita. The annual growth rate in agriculture averaged 4.4 per cent from 1979-2008, four times the population growth. Thus, China’s agricultural sector is able to feed 20 per cent of world’s population with 8 per cent of the world’s arable land. In contrast, Sub-Saharan Africa stagnated throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. Since the mid-1990s, however, Africa has seen a turn-around with rising GDP growth rates, remaining at 5 per cent per year since 2004. Agricultural growth has also accelerated (Figure 1 in Annex 1) (Fan et al, 2010)

In terms of food security, there has been a sharp contrast in performances: In China, grain output per capita reached 381kg in 2007 and food security at the national level has been achieved but disparity still exists among different regions, especially in the 271 poor counties in the western region (Xiao and Nie 2009, ix). The number of

undernourished people decreased from 178 million in 1990–92 to 127 million in 2004-06, and the share of undernourished people decreased from 12 to 10 per cent of the population in this period (FAO 2009). In Africa, however, average yield per hectare remained stagnated at 1 ton/ha for main cereal staples, and the number of undernourished people in Sub-Saharan Africa actually increased from 169 million in 1990–92 to 265 million in 2009, accounting for more than one-third of the total population (Josue Dione, UNECA; FAO 2009).

After three decades of reform, opening-up and broad-based economic growth, China has achieved the most rapid poverty reduction in human history: Using the new international poverty line of $1.25/day (in 2005 PPP), it is estimated that in the 24 years after 1981 over 635 million people in China were lifted out of poverty and the proportion of the population living in poverty fell from 84 per cent to 16 per cent (Chen and Ravallion 2008). In Sub-Saharan Africa, however, the share of people in the population living below $1.25 a day remained virtually unchanged—51 per cent in 1981 and 50 per cent in 2005. Moreover, the number of poor people almost doubled from 202 million to 384 million in the same period (Fan et al 2010).

China’s achievements in agricultural growth, food security and rural development have naturally drawn attention from the international community. How could China grow enough food on 8 per cent of the world’s land to feed over 20 per cent of the world’s population? In this broad context, the second event of the China-DAC Study Group on

“Agriculture, Food Security, and Rural Development for Growth and Poverty Reduction” was timely. This synthesis report focuses on the following three key issues that were discussed at the second event; it is not intended to be comprehensive.

• Key elements for China’s success in agricultural growth, food security and rural development. To what extent are these experiences and lessons relevant to Africa? (Section II)

• What has been the experience of African countries in these aspects: what has worked and what not? What are development partners’ experiences? What has been China’s approach in its engagement in Africa’s agriculture? (Section III)

• Going forward, what are the implications for African countries, China and established donors? How can Africa, China and established donors work together more effectively in improving Africa’s agriculture? (Section IV)

2.Agriculture in China’s growth and poverty reduction

A country possesses given natural endowments consisting of land (and natural resources), labor (and human capital), and capital (both physical and financial), which are the total resources available to be allocated to primary (including agriculture), secondary, and tertiary sectors. The endowments in a country are exogenously given at any

specific time but they are changeable over time. Empirical evidence shows that a country’s development strategy and priorities are crucially dependent on the country’s composition of total endowments at the specific development stage. In addition, natural endowments are directly linked with a country’s comparative advantage - an old concept with increasing importance in explaining growth and development in a globalized world.

2.1 Agriculture before and after reforms: what policy reforms have been implemented?

Agriculture is a matter of life and death for China, as a large country with a population of 1.3 billion and scarce land and water resources. In the long feudalist history, agriculture was considered the key for national security and social stability. However, China was a net grain importer for about a century according to the customs records dating back to 1863 (Zhong 2010). Food security was a remote and distant dream before the economic reforms initiated in 1978.

Past mistakes led to reforms. Why did China fail to achieve food security before the economic reforms? One of the reasons was the adoption of a strategy to promote heavy-industry development in a capital–scarce country. In 1949, the government inherited a war-torn agrarian economy in which 89.4 per cent of the population resided in

rural areas. At that time, industrialization as represented by heavyindustries was considered the symbol of a nation's power. However, the “forced industrialization strategy” was mismatched with China’s natural endowments at that time. The Chinese economy then had limited capital, high interest rates, and scarce foreign exchange because exportable

goods were limited. Agricultural products alone made up over 40 per cent of all exports in the 1950s. In order to accumulate the needed capital for industrialization, land was collectivised and the state monopolized the grain procurement. In addition, agriculture was heavily taxed and prices of agriculture products were depressed, so that savings from the agricultural sector were used for industrialization (Justin Lin and Yan Wang 2008). This system damaged farmers incentive for production, and as a result China remained a “shortage economy” from the 1950s to the 1970s; poverty was pervasive and large famines occurred in the early 1960s. The stagnation in productivity in part had prompted the economic reform in 1978.

Realizing the past mistakes, policymakers in China made a major transition to establish agriculture as the priority for reforms in 1978. Confronted with tremendous risk and uncertainty at the beginning of the reforms, China adopted a pragmatic, incremental and experimentation–based approach to reforms. Experimentation helped reduce risks and

facilitated self-discovery and a collective learning process to be carried out from the top to the bottom. As a result of these experiments, China developed many home-grown, unorthodox and practical policy measures.After 30 years of reform and opening-up, China has achieved three major structural transformations in agriculture:

•Collective farming was transformed to small-holder private farming;

•The share of agriculture in GDP has declined from 28 per cent in 1978 to 10.6 per cent in 2009, with the decline in employment share from 71 per cent to 39.6 per cent (NBS, 2010, WTO,2010)—which marked the beginning of an industrialized economy;

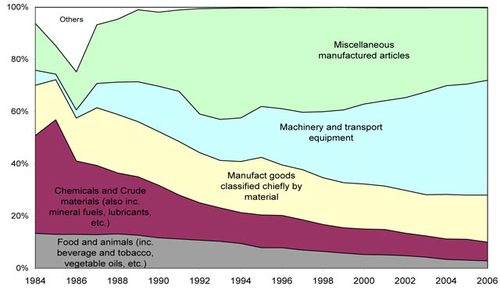

•The Chinese economy is integrated with the global economy, and its export structure is now in line with China’s comparative advantages. In the 1980s agriculture accounted for one quarter of Chinese exports and its share has declined to 2.5 percent in 2009, whereas labour-intensive manufactured goods account for a larger share in China’s exports (Figure 2).

Agricultural-related institutional and policy reforms can be divided into four periods, with different strategies and policies used in different stages. The first stage (1978-1984) was the adoption of a home-grown Household Responsibility System (HRS) for securing equitable land user rights, which tremendously improved smallholder incentives for production. Originally collective-owned land was distributed equally to villagers. In addition, a new pricing policy was launched which involved increased procurement prices. The introduction of the HRS is estimated

to have contributed to 60 per cent of the growth in the early 1980s (Lin 1992). Moreover, investment in the development and large-scale adoption of improved seed varieties, such as hybrid rice, also boosted agricultural growth and food security. As a result, rural income doubled from 1978 to 1984 and poverty rapidly reduced.

The second stage (1985-1993) focused on domestic agricultural marketing reforms such as fertilizer market liberalization and procurement system transformation from a mandatory quota system to a contract system. Initially, the “dual price” system was pervasive in the economy and farmers were guided by both market and planning price signals. In most cases market prices were higher than the procurement prices, and thus, reduction of quotas benefited farmers.

• The government played a crucial role in building a futures market for foodgrains including corn, wheat, soybeans, pork and cotton. In order to reduce the price fluctuation for agricultural products, with the support of top leaders Development Research Center started a research project on futures market in 1988. In October 1990, China’s Zhengzhou Grain Wholesale Market was established with the support of the government. It marked the beginning of the development of a nationwide wholesale (both spot and futures) market for foodgrains. In March 1993, China Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange got its new name and in May 1993 the futures contacts started to be traded. Since then, the futures markets in China have grown tremendously and provided clear market signals for agriculture production (Liao Yingmin 1999, page 341-344). Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange is now the world’s 12th largest

commodity exchanges in volume.

• Between 1985 and the early 2000s, agricultural markets were gradually liberalized with grain procurement quotas reduced. Domestic markets for foodgrain became more integrated. As a consequence, the prices of agricultural outputs rose in China during first 10 years of reform, and all farmers benefited (Li Guo et al).

The third stage of reform (1994-2001), focused on connecting farmers to markets by further opening up to international markets prior to China’s accession to the WTO, unification of the exchange rate, ending the monopoly of state trading in agricultural commodities as well as infrastructural development. These reforms resulted in increased market access and a decrease of domestic grain prices. In particular, China gradually reduced average tariffs for agricultural products from 42 per cent to 21 per cent in the period from 1992 to 2001. Furthermore, the country has implemented its commitment in WTO accession and reduced the tariffs from 21 percent to 11 percent in the period between 2001 and 2005.2 By the 2000s, domestic prices of most of agricultural commodities were close to those on the world market. (Guo LI et al 2010). Complementary investments were taken to protect the rural poor.

Throughout the entire reform era, the government has intensified its investment in public goods, supporting agriculture and rural development, and later complemented by co-financing from all levels of the government,

public service units and farmers themselves. Farmers contributions in the forms of voluntary labor and cash have been quite significant: In the period of 1980-2006, the proportion of self-financing by farmers themselves reached 34% in fixed asset investment, whereas investment from aid and FDI accounted for less than 4 percent (Yang Qiulin 2010). In the period from 1989 to 2000, annual inputs of rural labor to various projects were 7.22 billion workdays (Li Xiaoyun 2010). Most projects in rural China now focus on the provision of public goods. According to a survey of 9,138 projects (in 2459 sample villages), 87 percent was investment in public goods such as rural roads, irrigation, schools, and drinking water. About two thirds of public goods investments were into five types of projects: rural roads 21 percent, schools 14 percent, irrigation 14 percent, drinking water 12 percent, clinics 3 percent, and other public goods 37 percent. (Li Guo et al 2010)

Meanwhile, the government has consistently played a critical role in agricultural research and development and rural extension services over the last thirty years. After China’s WTO accession, the government has intensified its investment in agricultural research and development. Since 2000, the rise in research investment is higher in

China than any other country in the world. A system of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS) was established in all provinces with 39 institutions, as well as a system of agricultural universities. Overall there are about 2000 institutes and universities engaging in agriculture research and development. A nationwide system of agricultural extension services was also established even before the reforms. They have played a crucial role in disseminating agricultural techniques to the farmers (Zhang Lubiao).

Current stage (2002-present): China became a net importer of agricultural product in 2004 although the volume of trade continued to grow. Confronted with stagnating labor productivity in agriculture1 and widening rural-urban income disparities, raising farmers’ incomes has become the primary objective in the new era. The government has been implementing agricultural reform to improve farmers’ welfare, and mitigate rural-urban disparities, and more recently to stimulate domestic demand. In particular,

• The first policy is to protect farmers’ land-use rights. The new land reform was implemented to address the drawbacks of the household responsibility system, which is turned to an open ended-contract. So far, about 90% of farmers have received their operationcertificates. Since October 2008, farmers are allowed to transfer their land user rights through various forms, including subcontracting, and lease swapping. (WTO 2010)

• Second, to reduce and eliminate agricultural taxation (2004-2006),

which marked the ending of a 2,600-year tradition of taxing

agriculture. The tax burden was 8.1 percent of the total output in

agriculture in 2003, and it was eliminated to zero in 2007. Because of the reform, the financial burden of farmers has reduced by RMB

125 billion annually. (Tang Min)

• Third, to provide incentives for farmers to grow foodgrains. In the face of WTO accession foodgrain markets were liberalized, but other support measures including a minimum procurement price scheme in rice and wheat and direct subsidies were adopted. In 2008 the direct subsidies to agriculture reached over RMB 100 billion, accounting for 3.1 per cent of agricultural GDP(Li Guo et al 2010, page 24). Rural water resources management encompasses both drinking water and irrigation, both considered the responsibility of the government and requiring intensive investment. In 2000, 379 million rural people were without safe drinking water supply. During 2001-2009, after the government’s investment of about USD$7 billion, an additional 195 million people were provided with safe drinking water. Secondly,

irrigation is considered the basis for agricultural productivity and poverty reduction. Between 1979 and 2007, irrigated area was increased by more than 25% (Zhong 2010). A case study about Water User Association (WUA) shows it is an effective institutional design to improve farm-level irrigation management. Started in early 1990s, the Ministry of Water

Resources (MWR) selected 20 large irrigation districts to experiment with WUA, accompanied with water saving projects. After 2002, MWR and Ministry of Civil Affairs fully implemented WUA development in China, with about 200,000 WUAs established at present (Shen Dajun).

2.2 China’s Experience in Poverty Reduction and Rural Development

Agriculture serves multiple functions---it contributes to overall economic growth by providing food, labor and savings to nonagricultural sectors, but also provides employment and a social safety net for rural residents. On the one hand, agricultural growth has a farreaching impact on food security, farmers’ income, overall growth and

poverty reduction. In fact, growth in agriculture in China is estimated to have contributed four times more to poverty reduction compared to both growth in manufacturing and growth in services (Ravallion and Chen 2007). On the other hand, China’s main driver of economic growth is outside agriculture, in the labor intensive manufacturing and export sectors. Thanks to increased regional and global integration, productivity growth was mainly driven by the economy of scale and specialization in the coastal and urban centres. Thus, this section goes beyond agriculture to discuss nation-wide policies related to rural development and poverty reduction.

Diversification through the township and village enterprises (TVEs) was a significant institutional innovation with long term implications to rural development and poverty reduction. Despite their collective and public nature, TVEs provided production incentives to rural entrepreneurs and reduced their risks. Employment in TVEs increased from 28 million in 1978 to 95 million in 1988 at the peak (SSB 2007).

• First, the development of TVEs led to rising rural incomes and labour reallocation from agricultural to non-agricultural sectors. As a share of total national income, rural non-farm income in China rose from 4 percent in 1978-80 to 28 percent in 1997, and to over 50 percent in 2007. (Figure 3)

• Second, TVEs allowed room for experiments and self-discovery, as farmers experimented on various subsectors such as food processing, handicrafts, shoes, clothing and toys, and in the process some local comparative advantages were found. Many TVEs later were restructured into private partnerships, joint ventures or shareholding companies. This process marked the beginning of a rapidly growing private sector.

Move farmers out of agriculture. Thanks to the opening to international trade and investment through Special Economic Zones, China’s growth centre? moved to coastal regions and urban centers from the mid 1980s. Millions of jobs were created in the coastal regions in the labor intensive and export sectors, attracting an increasing number of rural migrant workers. The government has been gradually relaxing the restrictions for rural-urban migration and “labor exchange centers” were set up in coastal cities to help rural laborers to find jobs in urban areas. About 200 million rural laborers found jobs in urban areas with their annual income increased by 3 or 4 times (Tang Min). The average number of migrant workers increased from 100 million in the 1990s to 200 million in recent years. This large scale rural-urban migration and related policy changes have had a great impact on poverty reduction and rural development (Wang Sanqui et al. 2010).

Since the mid 1980s, China started to design and implemented programs specifically targeted at the poor. In fact China’s poverty reduction process is a learning process, with the strategy heavily influenced by international best practices, shifting from targeting the poor areas to targeting the poor villages and households. Officially, the post-reform poverty reduction in rural China has been divided into the following four stages:

• 1978-1985: poverty reduction was brought about by rural institutional reforms. Nearly half of the total rural poverty

reduction happened in this early stage of reforms (Lin, 1987, 1992, and Ravallion and Chen 2007).

• 1986-1993: a large scale poverty reduction campaign but with unclear targeting;

• 1993-2000: The 8/7 Poverty Reduction Plan aimed to lift 80 million people out of poverty in seven years, setting the “development oriented” strategy and targeting poor regions and counties;

• 2000-2010: the new Poverty Reduction Program (LGOP 2003). Agricultural tax was phased out in 2004-06 and the strategy of “whole village development” is implemented. Since 2007, a two legged strategy is being implemented including the “development oriented poverty reduction” and a social safety-net. (Huang Chengwei 2010)

Leadership and institutions matter for poverty reduction. The government’s strong leadership and commitment for poverty reduction was secured by establishing the following institutions: On May 16 1986, the Central Government created a high level coordinating agency, later renamed as “State Council’s Leading Group for Development Oriented Poverty Alleviation” in December 1993 (LGOP 2003). The group has been headed by a Vice Premier and consists of leaders from 27 major ministries including the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), Ministry of Agriculture (MOA), and Ministry of Finance (MOF). The Leading Group has been responsible for setting the national policies, strategies and plans for poverty alleviation, and the Leading Group Office has been created at the four levels - central, province,prefecture and county – of government in China. (Liu Jian 2009).

Capacity development through implementing projects. To implement targeted programs and projects, two centers were created under LGOP: the Foreign Capital and Project Management Centre (FPCMC) was created in 1995 to implement the World Bank and other internationally financed poverty projects in China. The Training Center

was created in February 1990 to provide trainings to officials from China’s poor areas. FCPMC and the Training Center were also created at the provincial levels under the respective provincial LGOP. Capacity building activities through training and “learning by doing” made sure that central government policies and projects could be implemented at the county and village levels These institutions were able to mobilize large amounts of resources, allocate the resources to the designated poorareas, and implement large scale projects. The LGOP system has also provided a stable career path and a platform for development practitioners so that they have incentives to perform well and stay in the system and be promoted later. Capacity development in the LGOP system has been sustainable in part because of the opportunities provided by an enabling macro environment provided by a stable and growing economy (He Xiaojun, IPRCC 2010).

Public financing has been complemented by state banks and international donors. The government’s poverty reduction drive is enhanced by poverty reduction funds from both the central and local government. At the central government level, the poverty reduction funds include the poverty loans managed by the Agricultural Bank of China (ABC), funds for “cash for work” programs channeled through NDRC, as well as the direct fiscal input channeled through the Ministry of Finance system. The average annual rate of growth for the total Poverty Alleviation (PA) funds was about 10 per cent from 1986 to 2008, which is slightly higher than the GDP growth rate during the same period (Figure 3). The ratio of the combined “cash for work” fund and fiscal funds to total central government budget expenditure between 1986 and 2007 was around 2.5 per cent on average. On average, two thirds of the PA funds for the poor counties were from the central government; around 10 per cent was from international and domestic donors, and 5 per cent from the provincial governments. (Wu Zhong and Cheng Enjiang 2010)

Currently, a new comprehensive poverty reduction strategy is combining rural development with social protection, in order to address of rising rural –urban disparity, inequality of opportunities in education, health, employment and rural finance for self-development. These include

• Improving the basic conditions for production and livelihood through the “whole village plan for development”. There are 150,000 poor villages in China, and by the end of 2009, village plans for poverty reduction have been implemented in 108,400 villages.

• Stepping up the financial support through mobilizing social funds and promoting rural- and microfinance. The number of village-level funds for mutual assistance in the poverty-stricken villages increased dramatically from 319 in 2006 to 9,003 in 2009, covering 940 counties.

• Enhancing human capital by training laborers and preparing them for migrating to urban areas. Since 2004, a fiscal fund of RMB 3 billion has been allocated for this purpose and over 4 million laborers have been trained, leading to a higher probability of finding a job and a rising monthly salaries. In addition, 6.2 million poor people were voluntarily moved out of the areas not suitable for human habitation. (Huang Chengwei 2010)

• Promoting rural social development. A rural cooperative health care system was established with more than 90% of farmers now participating in the system. By 2007, 9-year compulsory education became free, and it is being gradually extended to rural vocational education. Since 2009, the government has started to pilot a rural pension system. By the end of 2010, about 30% of farmers will be covered by the rural pension system. (Tang Min)

International multilateral and bilateral donors have played an active catalyzing role for poverty reduction and rural development in China. The donor agencies have made particular contributions by introducing new ideas, concepts and methodologies for poverty reduction in China and by experimenting with new concepts and methodologies with donor funded and government implemented poverty projects in China. Since the mid 1980s, the LGOP system has utilized foreign ODA and other assistance for poverty reduction in the amount of USD$1.16 billion, including some USD$460 million since year 2000. (Huang Chenwei 2010)

• In the 1990s, the Chinese Government cooperated with the World Bank and implemented four large scale integrated poverty projects. These projects covered 119 poverty counties in 8 provinces of China and more than 10 million poor population benefited from the projects.

• Since 2000, LGOP has cooperated with various international organizations, bilateral donors and international non-government organizations (INGOs) and introduced a number of new ideas and concepts into China, including participatory poverty planning, community driven development (CDD), government procurement, and provision of support to NGOs in poverty reduction (LGOP 2008, He Xiaojun 2010)

• In the 1990s, the Chinese government imported the Grameen model of microfinance through cooperation with the UNDP Office in China. The World Bank and ADB ran pilot projects relating to community development fund Rural households receiving poverty reduction credit increased from 1.52 million in 2001 to 1.97 million in 2009 (Huang Chengwei).

Box 1. Development Aid and Foreign Loans in China’s Agriculture

In the 25 years between 1981 and 2008, international aid towards China’s agricultural sector experienced ups and downs: During the period of 1981-85, the Chinese government just began to accept foreign aid to developing agriculture- The volume was USD$395 million in the five year period. In the mid 1980- 1990s, the volume of foreign aid in agriculture increased gradually, reaching to a peak of $2 billion between 1991 and 1995, and then declined afterward. As to the regional allocation, the majority has been distributed to the middle and western regions of China.

Entering the new century, the amount has been stable at $160 million annually. See figure 1.

Box figure 1. Composition of Foreign Aid in China’s Agriculture and Infrastructure (2002-2008) (USD million)

Source: based on data from OECD-DAC database. Sectoral allocation is not available before 2002.

From 1981 to 2005, the volume of foreign loans into China’s agriculture totaled $6 billion US dollars, which encompassed more than 200 projects. Among them, the foreign loans from World Bank, Asian Development Bank, International Agricultural Development Fund, and foreign governments (including international commercial loans) are respectively $ 4.62 billion, $ 0.35 billion, 0.48 billion, 0.52 billion, accounting for 77%, 6%, 8%, and 9% of the total, respectively (page 48, NDRC 2009).

Impact: A) International aid and loans have broadened the channels of funding in agriculture, enhanced the construction of core projects and improved the production and living standards of farmers. B) It has provided support to solve the urgent problems in agriculture, including food security, diversification, and agricultural commercialization or “industrialization”. C) It has introduced the advanced technology and management ideas and promoted system innovation in agriculture. D) It has strengthened the international exchange and helped to build theinstitutional capacity in the field of agriculture.

Source: Yan Wang, summarized based on NDRC 2009 on foreign loans.

2.3. Key Elements for China’s success in Agriculture

It is well recognized that agriculture is a powerful engine of growth –it produces food for the rest of the economy, supplies labour and savings to other sectors, supplies low cost food to keep the wages down, and exports commodities to earn foreign exchange. After discussing reform and policy measures in agriculture (section 2.1), and rural development and Poverty reduction (section 2.2), this section focuses on several lessons and remaining challenges.

Learning from past mistakes. Looking back at the pre-reform history policymakers realized that China paid a high price for a strategy attempting to defy its comparative advantage to strive for early industrialization. Despite significant efforts to invest in rural infrastructure for electrification and irrigation systems, agricultural productivity was still low due to distorted prices and incentives. Realizing the past mistakes, a decision was made by the Chinese government to give priority to agriculture, (labour-intensive) light industry and people’s consumption. This shift in strategy led to early gains by a majority of the population and won public support for subsequent reforms in other areas such as trade and investment regimes.

China’s agricultural development has been driven by the “organic combination” of three forces, i.e. the state, the market and farmers. China’s agriculture was transformed into a small-holder farming system which needs support from the government and the market system. Long-term agricultural development strategies coupled with public investment in agriculture have substantially reduced the risk and cost for smallholder farmers. Therefore, China is able to effectively overcome the three major difficulties in technology, market and institutions/systems that most developing countries encounter. Market mechanism alone is not sufficient, it is critical to have the leadership of a

visionary, responsible and capable government. (Li Xiaoyun) It was the government’s determination and commitment for growth and poverty reduction supported by strong institutions and an increasing amount of resources that let to dramatic reduction in hunger and poverty. (Huang chengwei)

Chinese agricultural strategies can be summarized as “first relying on government policies and second on science and technology”. Apart from the establishment of the land user right and the market reform incentive system, the core strategies also include attaching importance to science and technology and to the promotion of agricultural development through science and education. Institutional reform has led to a one-time increase in rapid productivity growth, after that agricultural growth has relied on inputs and technical progress. Since 1985, the total factor

productivity increase in agriculture could be attributed to technical innovation and dissemination. One analysis shows that the narrowly defined technical progress has led to rising agriculture output, with the rate of contribution rising from 17 percent at the end of 1980s to 41 percent in early 2000s. (Wang Sangui 2008, 2010). The government has

played a major role in promoting R&D in agriculture, setting up research institutes, investing in education and research, and supporting agriculture extension systems (Zhang Lubiao). In China’s grain crops and livestock production, the application of improved varieties and new technologies has reached more than 90%, which successfully combines scientific technology with small-scale agricultural economy transformation (Li Xiaoyun).

Accumulation of human capital, social capital and infrastructure capital in the pre-reform era had provided important preconditions for agricultural growth and rural development and poverty reduction. The primary education enrollment rate was raised from only 20 percent in 1949 to 95 percent in 1978, and the infant and maternal mortality rates declined dramatically. The public investment in education and health has laid the foundation for human capital accumulation in the rural areas. In addition, a significant number of irrigation, rural electrification, and water conservation projects were completed in prereform and post-reform eras (Wang Sangui 2008). Chinese farmers have put enormous investment in small water conservancy facilities and water and soil conservation in the community and at the small watershed level, thereby ensuring continuous improvement in agricultural productivity. Thanks to the leadership and social capital in the rural villages, the spirit of “poor helps the poor” has continued until today which greatly facilitated the community-based rural development work and poverty alleviation.

Learning from international development partners for China’s development, especially in the areas of capacity development. Since modern agriculture has drawn on the agro-development experience of developed countries, China’s agricultural education and agricultural research are largely dependent on learning and introducing technologies from developed countries. During the learning process, China has followed the principle of introduction, digestion and utilization, and has organically integrated the technologies and management approaches conducive to China’s agricultural development into the system of agricultural technology management. (Li Xiaoyun) This spirit of mutual learning, adapting to local conditions and constant innovation is of relevance to African practitioners.

2.4. What is relevant to Africa and other developing countries?

China and the 53 African countries have vastly different history, geography and demography – there is a sharp contrast in history of the nation states and its consequences for institutions, cohesion and elites, and there are differences in the natural endowments, size of the domestic markets, demographic patterns, and stage of development (Losch and Li). But there are also similarities in the initial conditions and in the challenges ahead. Participants recognized that even though China’s experience may not be directly replicable in Africa, inspirations could be drawn from China's experience of a strong public policy backed by investment in human capacity, social capital, infrastructure, and science and technology. Three lessons may be particularly relevant to African countries.

First, a country’s development strategy differs greatly according to the natural endowment of the country, but in the initial stage, agricultural growth and development is always a priority. Some countries may not have comparative advantage in agriculture (such as China); rapid growth in agriculture is still a necessary condition for the industrialization at a later stage. This is because agriculture can serve multiple functions, a) to provide food, labor and savings for industrialization and urbanization, and b) to provide a social safety net for rural poor. Even though the main propellers of economic growth may lie in other sectors, agriculture is fundamental to a broad-based and pro-poor growth. In the long term, however, a “comparative advantage following” strategy has allowed China to reach where China is today (Justin Lin and Yan Wang 2008).

Second, China’s model facilitates experimentation for selfdiscovery and self-development by smallholders, and public and private partnership in financing agriculture and rural non-farm sector development. Without waiting for adequate investment from the central government, farmers have contributed to build rural infrastructure through co-financing, “cash for work” program as well as voluntary collective work. Over 34 percent of fixed capital investment in rural areas was financed by farmers themselves. International aid and FDI in agriculture constitute a small percentage of total investment – on average, less than 3 percent between 1981 and 2008 (Yang Qiulin 2010). Farmers participate in the decision on which crops to plant, and which projects or enterprises to select and contribute to, and are held responsible for their profits and losses. This spirit of self-help, commitment, and accountability may be useful for African countries.

Third, government-led and development-oriented poverty programs have been rooted in the thousand year-old traditions of not only “offering fish” but also “teaching how to fish.” The government has been focusing on improving the precondition for self-development in the poor areas of China. The targeted anti-poverty programs have also provided access to education, health services, micro-financing, and trainings to the poor, which tend to improve their capacities for selfdevelopment. (Wu and Cheng 2010). Among the four pathways out of poverty, agricultural labor productivity emerged as the most important,especially at the early stage of development. Rural–urban migration and rural non-farm sector are also important for the poor in areas with less favorable agricultural endowment (Wang Sangui et al 2010). These philosophies and approaches have implications for China’s engagement in Africa which encourages ownership and self-development.

Some not-so-positive lessons deserve close attention by African countries. A series of problems exist in China’s agricultural development, including for example, a vague land-user right for farmers, a dualistic structure which causes rural urban disparity and inequality, agricultural environmental pollution caused by subsidizing fertilizers and pesticides, and degradation of natural resources resulting from highly intensified investment and development on land. (Li Xiaoyun) In the recent years, the consequences from many years of intensive growth in exportoriented

sectors and inadequate attention to agriculture, farmers and rural development have surfaced, which led to the call for a more scientific, people centered and harmonious pattern of development. A reciprocal policy of “industries nurturing agriculture” “urban areas nurturing rural areas,” is being designed to promote the equalization of basic public services in the poverty-stricken areas. The minimum livelihood guarantee system was initiated and implemented in rural areas in 2007 (Tang Min). Still, China has a long way to go before achieving a balanced, equitable and sustainable growth pattern and harmonious development.

3.Africa’s Agriculture Development:Challenges and Opportunities

This section discusses agricultural development strategies being implemented in Africa, what approaches have been used by established donors, and what China and established donors can learn from each other in their engagement in Africa.

3.1 What has worked in Africa and what has not?

Over the last 10 years agricultural growth in Africa has accelerated, driven by macro and sector policy changes (Figure 1). A number of significant challenges are facing the agricultural sector in African countries, however. In response to growing demand for food and agricultural goods many countries are increasing their imports, but intraregional trade remains relatively low. One of the significant challenges is bridging the disconnect between regional supply and demand. At the same time, there is an urgent need to address the under-capitalization, low productivity, and competitiveness of Africa’s agriculture. Other significant challenges identified include addressing African farmers’ disconnection from input and product markets, and addressing the fragmentation of African food and agricultural economy. (Josue Dione UNECA) In addition, after a decade of decline, Official Development Aid (ODA) to support Agriculture remains too small and better priceincentives for agriculture are needed. (Hans Binswanger)

Donors approaches. Since the mid 1980s, aid to agriculture has fallen by 43% but recent data indicate a slowdown in the decline, and the beginning of an upward trend (OECD 2010). The two-decade long decline in agricultural cooperation brought agricultural aid down from around 16% (1977) to around 4% (2004) of total ODA to Africa. (Asche 2010) “It was the expectation that after price reforms and dismantling of public monopolies the private sector would take over… However, in core areas neither foreign nor domestic private capital stepped in.” (Asche2006). The consequence was that average yield per hectare remained stagnated at 1 ton/ha for main cereal staples throughout Africa (with some exceptions). Expansion of African food agriculture thus happened mainly by expansion of cultivated area from 125 Million ha (1960) to 200 Million ha today. (Figure 4)

Global Value Chains. In contrast to food production, dynamic integration of Africa into global agricultural markets increasingly takes place via global commodity or value chains (GVC). While for some products this is a very old phenomenon (cocoa, coffee, tea, tobacco), entirely new chains have been developed, such as the horticultural and

floricultural value chains or fish exports from Lake Victoria. International aid agencies found GVCs as a promising area of development support. Aid projects built on two critical observations: (1) farmers should be helped to get a fair(er) share in value chains proceeds; (2) smallholder farmers have typical problems to comply with quality

standards. As a result, helping Africa’s agriculture to better compete in global value chains has become an important work area for most international aid agencies. (Asche 2010).

The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), is a framework for policies, strategies and partnerships for agricultural development that was endorsed at the highest political level and includes a commitment of 10 percent budget allocation towards agriculture. The primary objective is to eliminate hunger, reduce poverty and food insecurity, and to expand agricultural exports. It is implemented through four integrated pillars:

1. extending the area under sustainable land management and reliable water control systems;

2. improving rural infrastructure and trade-related capacity for market access;

3. increasing food supply and reducing hunger; and

4. agricultural research, technology dissemination and adoption with cross-cutting capacity strengthening.

The CAADP targets for 2015, reflecting the MDGs, are to: improve productivity of agriculture to attain an average annual growth rate of 6 percent, with particular attention to small-scale farmers,especially women; have dynamic agriculture markets within countries and between regions; have integrated farmers into the market economy

and have improved access to markets to become a net exporter of agricultural products; achieve more equitable distribution of wealth; be a strategic player in agricultural science and technology development; and practice environmentally sound production methods and have a culture of sustainable management of the natural resource base.

Innovative approaches. There are numerous examples, throughout Africa, of smallholders and pastoralists demonstrating remarkable capacity for innovation. For instance, in regards to improving farm productivity, science-based innovations such as tissue culture bananas, NERICA rice varieties and hybrid maize have had a significant impact. There is an urgent need though to accelerate adoption of such technologies by facilitating learning among different actors. Another key area identified in CAADP is to develop innovative approaches for improving human and institutional capacity, particularly academic and professional training. As an example, FARA is involved in a recent initiative to link university education, agribusiness and research, known as UniBRAIN, with the objective of developing graduates with the entrepreneurial and business skills relevant to the development of Africa’s agricultural productivity. (Monty Jones, FARA)

Donors approach. In 2007-08, total annual average aid commitment to agriculture amounted to USD 7.2 billion. Among DAC members, the largest donors in 2007-08 were the United States (on average USD 1.4 billion per year), Japan (USD 1 billion) and France (USD 582 million). A large proportion of aid in agriculture has been directed to Sub-Saharan Africa (31%) especially the low-income countries. (OECD April 2010). Several new innovative approaches have been developed, including the Sector-wide approach (SWAps), Coalition for African Rice Development (CARD), Feed the Future initiative, Sectoral Intervention Framework, and so forth (see section 3.4 Donors perspective).

3.2 China’s Aid, Trade and Investment Strategy in Africa: Experiment and Self-Discovery

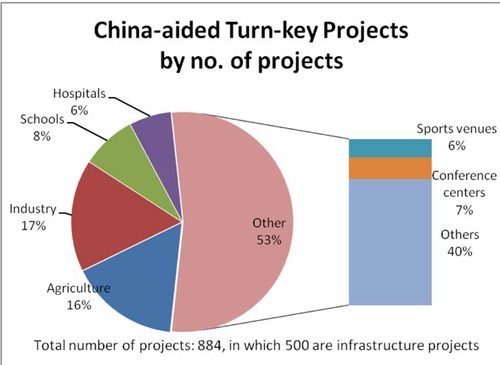

The shift in Official Development Aid (ODA) from agriculture to the government sector by established donors has opened the way for emerging donors in this sector. These emerging donors and investors bring with them seeds,

marketing techniques, jobs, schools, clinics and roads. Since 1959 when China started its agricultural assistance program, 44 African countries have hosted Chinese agricultural aid projects, and the Chinese have developed 8 84 farms through their aid and investment projects. Agriculture made up about a fifth of the 884 “ turn- key” projects

constructed by China’s aid program between 1960 and 2006.

At the 2006 Beijing Summit of the Forum on China and Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), China confirmed its long-term commitment to a “new type of strategic partnership” with Africa in the 21st Century, “featuring political equality and mutual trust, economic win-win cooperation” (FOCAC 2006). China’s increased engagement in Africa is unique as it combines trade, aid, investment, and knowledge exchange, including transferring agricultural technology. Drawing on its experience in domestic poverty reduction programs, China has placed greater importance on enhancing poor people’s productive capacity. During the 1990s, the consensus grew among Chinese experts that China’s traditional (large scale) agriculture projects were not sustainable without continued Chinese support. Therefore, 15 new “Agricultural Technology Demonstration Centers” are being constructed to facilitate experimentation. The discussion below follows the sequence of trade,aid and investment.

China-Africa trade in agriculture. Overall trade between China and Sub-Saharan Africa has been growing much faster than overall Chinese trade for the past ten years, reaching over USD $107 billion in 2008. However, trade in food and agricultural raw materials as share of total trade between China and Africa remains small—around 3 percent in 2008 both in exports and in imports (Fan 2010). Some researchers contend that China Africa trade reveals a strong asymmetry (Figure 5). While agricultural exports from Africa to China are dominated by agricultural raw materials, agricultural imports have been focused on food. Most prominent are African exports to China of cotton and tobacco. The general China-Africa trade patterns have not directly benefited African agricultural and rural development. (Fan 2010; and Chaponniere, Gabas, Zheng, 2010) On the other hand, Chinese food exports which are competitive on the world market are making inroads into the African market (Rozelle, 2007).

Official development aid from China to Africa is estimated to have almost quadrupled from USD $684 million in 2001 to USD $2.5 billion in 2009, with preferential loans and credits from China’s Eximbank (Export-Import Bank) growing the fastest (Brautigam 2009

page 170). As pointed out in chapter 1, no official data is available on the decomposition of China’s aid to Africa. In the area of agriculture, Chinese aid in past decades has moved away from large-scale stateowned farms to support for smallholder farmers in Africa. China has also experimented with new methods of combining aid and economic cooperation such as joint ventures, cooperation contracts, and publicprivate partnerships (Brautigam and Li 2009). China’s aid in agriculture has gone through three stages.

• In 1960s and 1970s China helped build a large number of farms in Africa, totalling 87 projects covering 43,400 hectares. These farm assistances were managed by Chinese experts and financial assistance. However, this kind of aid was considered not sustainable and confronted difficulties when these farms were transferred to the recipient governments (Cohd and Ciad, 2010).

• From the mid-1980s onwards, more of these bilateral agricultural projects become joint ventures looking for

profit under the “go global” strategies. The Chinese government encouraged and allowed some enterprises,

especially state-owned enterprises, to join in foreign aid work. China’s State Farm Group and provincial state farm groups began restructuring farms in Africa. Thus the farm model changed from purely state-owned to government-supported enterprise. These farms are managed by Chinese personnel who hire local farmers as workers to produce agricultural products for the local market (Cohd and Ciad, 2010).

• The third period started in 2000, with the creation of the Forum of China-African Cooperation. China is actively applying the South-South Cooperation mechanism and other multilateral mechanisms to extend agricultural assistance to Africa. By the end of 2005, 145 agriculture aid projects have been established in the form of constructing farms, testing stations, technology demonstration centres, and sending agricultural experts. Up to the end of 2008, Chinese companies had invested in Africa in the establishment of 72 agriculture enterprises, with a direct investment of 134 million US dollarscoming from the Chinese side.

Box 2: China’s Aid in Africa’s Agriculture: Lessons and New Approaches

Lessons from aid projects. China is learning from its own experiences in development cooperation. In particular, a paper by Director Xue Hong (CAITEC, MOFCOM) was informative about various development cooperation approaches in Africa.

Xue first describes the outcomes of five cases of China’s aid projects in Africa, including the Mubarali Rice Farm of Tanzania; the Kibimba Rice Scheme, Uganda; the Sugar Conglomerate in Mali; Magbass Sugar Complex, Sierra Leone; and Anie Sugar Refinery (Complexe Sucriere D’Anie), Togo. Most projects were successful in the first stage after completion, but could not remain sustainable after a few years due to numerous difficulties in the recipient countries. He concludes that aid projects can be made sustainable if they can be transformed into commercially viable joint ventures by the two sides, as in the case of Sukala Sugar Conglomerate in Mali.

Xue Hong sees that there is a need to reassess China’s approach of providing development assistance, and shift to a model that is “led by (public or private) enterprises while facilitated by the government through R&D and demonstration centers.” “The government should intensify policy support, enhance information communication and research, create effective coordination system, encourage domestic and competent state-owned or reputable private enterprises to conduct development independently in the form of proprietorship, joint ventures and cooperation, using funds raised through various channels ensuring the sustainability of cooperative projects.” (Xue Hong 2010 page 17).

New Development: According to a new report on China-Africa Trade and Economic relationship Annual Report 2010, agricultural projects accounted for 16 percent of total number of China-aided complete plant or turnkey projects (142 out of 884) by 2009. However, the monetary amount for these projects is not available.

Source: CAITEC, MOFCOM, October 14, 2010.

In 2009, China’s FDI in Arica’s agricultural sector amounted to about USD $30 million. This includes investments from wholly Chinese-owned companies, joint ventures or cooperative activities, in countries such as D.R.Congo, Sudan, Malawi, and Zambia. One example is that Chinese companies and the China-Africa Development Fund launched a project worth over $20million for cotton cultivation and processing in Malawi, benefiting 50,000 households in 2009.

In 2009, under the FOCAC framework, the construction of Chinese-aided agricultural technological demonstration centers commenced in Benin, Liberia, Mozambique, Uganda, Ethiopic, Sudan, Cameroon, and Tanzania. Between 2007 and 2009 China sent 104 senior agricultural technology experts to 33 African countries, helped in building agricultural infrastructural facilities such as grain storage, rural roads and water in Zambia (page 15-16, CAITEC 2010).

Direct investments (FDI) and comparative advantages. In general, foreign direct investment comes naturally to sectors where the country has a comparative advantage. In China, FDI has been concentrated in light manufacturing sectors, where China has a comparative advantage. In 2007, FDI in agriculture accounted for only 1.5 percent of total FDI in China (Brautigam 2009, and Wang Zhile, CAITEC). Some African countries, on the other hand, do have

comparative advantage in agriculture, especially in Mali, DRC, Sudan, Tanzania, and Zambia, where Chinese FDI has some potential (LuXiaoping 2009). In 2009, China’s outward Foreign Direct Investment(FDI) in Africa’s agricultural sector amounted to about US$30 million, however, trend data on the flow of Chinese FDI by sector is not publically available. With high prices of food, foreign investment in land in developing countries has increased. Chinese state-owned enterprises have been involved in discussions about land acquisition in Africa, but the deals have so far not been large. The established “Friendship Farms” in some countries are owned by a Chinese parastatal organization, but are usually below 1,000 hectares (Cotula et al. 2009). The nature of China’s investment activities in Africa is multi-faced: Some are managed by the Central Government with the transfer of technical assistance. A significant number are carried out by provincial level enterprises but with the support of the China Africa Development Fund or with incentives from host countries as is the case of Zimbabwe and Zambia.

3.3 Perspectives of Africans:Feedback on China’s support to Agriculture

African perspectives are based on the five-country consultation organized on April 13, 2010, including representatives from Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, and members of the China-DAC Study Group. After two presentations provided from the perspectives of China and Africa, participants discussed 3 main topics: What lessons can be learned from China’s experience? What policies and strategies have donors and China been pursuing to promote agricultural growth, food security and rural development in African countries? In view of

population growth and climate change, what role can innovation in agriculture play to provide opportunities for job growth and poverty reduction in Africa?

First, participants agreed that China’s experience had a number of lessons for Africa noting especially the success at intensification and productivity increases by smallholders. Kenya noted its own experience in the development of the cut flower export industry. Mali noted that they had undertaken many projects aimed at agricultural intensification and a key criteria for success was the integration ofdomestic and international markets for production. They discussed China’s approach to financing of agricultural inputs, development of infrastructure, rural credit and financing, and management of food crop surpluses.

Second, they also underscored that Africa has the potential to develop smallholder agriculture as a prelude to larger farm development. Liberia noted that smallholder agricultural development would necessarily play a central role in reducing poverty in a country where productive capacity had been severely reduced by years of conflict.

They cited the importance of the Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Program (CAADP) and suggested that China consider using the CAADP as a channel to support countries through programmatic funding.

Third, participants noted that China was playing an important role in supporting the development of their technical capacity through training and the establishment of technical centers, including a planned center in Liberia. They were interested to hear about China’s approach to fertilizer subsidization, which had kept prices stable in real terms as the prices for food crops increased, and resulted in greater onfarm incomes. Complementary measures to absorb market surpluses, including price protection through strategic storage of excess production were also discussed. Participants discussed China’s experience with technical innovation and productivity increases especially to understand how small farmers changed longstanding practices.

Fourth, one of the challenges would be public finance in agriculture. Participants discussed whether the budget allocation goals set out in the CAADP would be attainable given that they were dependent on donor commitments and aid budgets are highly constrained. Experts, however, noted that domestic finance is likely to be more important to continue to support agriculture in Africa, and countries should be cautious in relying on aid pledges to finance the CAADP. Participants also discussed the potential opportunity and challenges for agriculture from climate change. The complexity of impacts suggests that there may be cases where climate change could enhance agricultural growth, and that agricultural technology needed to be developed to take advantage of these opportunities where they existed.

In sum, participants from four African countries agreed that “there is real scope for mutual learning especially as it relates to smallholder development, food security, intensification, and adapting market mechanisms to support agriculture.” They provided numerous examples of areas where collaboration with China is already underway and where they believe that there is an opportunity to capitalize on a more favorable market environment than in past decades. Participants also believed that there would be gains from having agricultural delegations including farmers visit China. (ACET Summary, April 2010)

3.4 Perspectives from the Donors:New Approaches and the Land Grabbing Issue

The established donor community in general welcomes China’s emergence as a donor. Chinese investment in African agriculture brings capital and technology. For example, the introduction of water-saving technologies and soil-related techniques such as tillage and planting methods are particularly beneficial. However it could be argued that

these examples refer to farms established in an earlier phase of China’s engagement (Chaponniere, Gabas, Zheng, 2010). To enhance learning, this section introduces several new innovative approaches.

Over the years, established donors have made many efforts to harmonise their aid through greater transparency, better information sharing, and increased co-ordination. In particular, several innovative programs and modalities have been developed. First, Sector-Wide Approach (SWAp), also increasingly referred to as a program-based approach (PBA) is a specific aspect of budget support. A SWAp is where donors disburse funds to a specific sector within a national budget to directly support a recipient government’s strategy. The government is firstly expected to develop an overall strategy for a particular sector (such as agriculture), which donors will pledge support for, encouraging the government itself to co-finance the programs. Providing aid in the form of SWAps is claimed to be more efficient (less costly) than funding numerous individual projects, although initial concerns highlight that many donors continue to provide funds for specific projects, despite also contributing to the pooled funds, adding to the complexity of the process. Despite mixed results, the approach continues to be utilized in different forms by a range of donors in the agricultural sector. (Cabral 2009)

Second, Coalition for African Rice Development (CARD). Initiated at the Yokohama Conference in May 2008 and led by a partnership of Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), NEPAD and JICA, this project aims to double the rice production in SS Africa within 10 years through supporting smallholders by providing the new resilience rice varieties. Its functions include sharing statistical and technological information, facilitating donor coordination at the project level, increasing investment in rice production, and supporting research and development for new varieties. The funding could also be used for rural infrastructure. This is a part of the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD IV), supported by many donors and is fully consistent with the CAADP. 1

Third, Feed The Future. In response to the commitment at the 2009 G8 Summit of global leaders to “act with the scale and urgency needed to achieve sustainable global food security” the US pledged $3.5 billion over three years to advance action that addresses the needs of small-scale farmers and agribusiness, and harnesses the power of women to drive economic growth. The principles underpinning the Feed The Future (FTF) initiative are: comprehensively address the underlying causes of hunger and under-nutrition; invest in country-led plans; strengthen strategic coordination, including with civil society and the private sector; leverage the benefits of multilateral institutions; and make sustained and accountable commitments. The FTF initiative is designed to be flexible and innovative, reflecting ongoing lessons learned - Small case studies will be used to develop sustainable, scalable solutions to food insecurity. One example is the production of shallots along the Dogon Plateau in Mali, where the Integrated Initiative for Economic Growth program (IICEM) provided technical expertise to stakeholders all along the value chain, including production, post-harvest storage, processing and marketing. USAID also initiated a partnership with the World Bank and FAO to reorganise the farmers’ cooperative and improve the transparency of donor aid.

Fourth, Sectoral Intervention Framework – Rural Development. AFD assistance in rural development is directed towards the following priorities: loans to agro-food and agro-industry companies; supporting financial institutions related to agricultural sectors, including innovation; financing infrastructure and strengthening institutional capacities. In Sub-Saharan Africa the focus is more specifically on the food crop production chain, agro-business and smallholder farming. (JY Grosclaude, AFD) Fair Trade & Organic Fair Trade Cotton. AFD is also supporting projects that tap into the increasing consumer demand for ‘ethical’ products. One such area is the cotton industry in five West and Central African countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Mali and Senegal. African cotton already enjoys production methods that fully meet criteria for fair trade. By promoting the sustainable nature of African cotton production, there is a real potential for Africa to benefit from the keen interest in fair trade cotton.

Since the food crisis of 2007, attention has been given to “land grabbing” in Africa and China has been labelled by some as a land grabber pursuing a food security strategy. Although the actual facts have yet to be investigated, information gathered from international organizations and NGOs offer a picture of what is going on. GRAIN, a

Spanish-based NGO, has monitored media articles that reported around 180 land deals at varying stages of negotiation. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) documented reports on 57 land deals. IIED, FAO and IFAD compiled a large database on this issue. The International Institute for Sustainable Development has analyzed the water component of foreign land purchases (Cotula and Vermeulen, 2009; Mann and Smaller, 2010).

Among the 34 large scale projects recorded by IFPRI in Africa from 2006 to 2009, “Chinese investors are involved in only four which are questionable”. The survey of large-scale land appropriation in Africa shows that these interventions are not new and seem to be intensifying in the recent years. It is difficult to appreciate their size and their agricultural practice (labour intensive or not, ecologically intensive or not, etc). Available information shows that Chinese investments are aimed to supply local or regional market and not to the Chinese market. The exception

could be investments in biofuels which may be export oriented and target the European market. (Chaponniere, Gabas, Zheng, 2010)

4.Going Forward

Africans have started to take leadership: a continental-wide strategy for agricultural development is clearly embodied in the four pillars of the Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Program (CAADP), as shown above. It also lays out a framework for how all stakeholders including the donor community should coordinate and

address the challenges of African agricultural productivity to maximize effectiveness. The changes required to achieve these (and broader MDG) targets, call for revolutionary vision, commitment, investment and action, with many options for mutually beneficial collaboration between African and non-African institutions. (Monty Jones, 2010)

• One strategy is to focus on developing regional value chains of strategic agricultural commodities. This includes focusing on filling the regional gaps in production and trade for strategic food and agricultural commodities, and deepening regional integration to promote the development of coordinated value chains of strategic goods and agricultural commodities. (Josue Dione UNECA)

• A number of action points for international development assistance have been identified. For example, supporting research and development to increase farm-level productivity; supporting investment in production and market infrastructure, especially irrigation, farm-to-market transportation, sustainable rural energy access and affordable communication technologies; reduce risks and vulnerability; and enhance environmental services and sustainability. (World Bank, Agriculture Action Plan 2009)

• Another area is in supporting agro-industry and agri-business development, through joint venture FDI, in areas such as agricultural inputs (i.e. machinery), processing of products, and innovative contractual arrangements (i.e. contract farming).International development assistance could also be utilized to facilitate access to financing and trade in strategic commodity value chains, such as promoting joint agricultural investment forums and enhancing trade through removal of barriers to improved market access. (Josue Dione UNECA)

Challenges of investing in agriculture in a changing world. The conditions for the integration of Sub-Saharan African countries into the world economy today are very different from those of both developed and ‘emerging’ economies. The realities of demographics, economic transition and global integration require new strategies and new thinking. Three major challenges have been identified. First, at the macroeconomic level: despite dynamism in recent years most African countries’ economic structure remains agriarian economies with a low level of economic diversification. Second, demography: few countries have initiated demographic transition, i.e. birth rates are still high

resulting in rapid population growth. Third, how to absorb the growing working population, and how the agricultural sector will address the food requirements of a growing population. (Jean-Jacques Gabas, Cirad). Fourth, the potential impact of climate change will hurt the poorest and most vulnerable countries and groups in the world (World

Bank, WDR 2010).

It was in this context that participants at the agriculture event welcomed China’s intensified engagement in Africa’s agriculture and rural development. “For many stakeholders and observers, China’s involvements might bring opportunities to African states and local farmers. Nevertheless one should pay attention to possible challenges

and problems because it is perhaps in agriculture where China may have a significant impact on the continent’s future.” (Chaponniere, Gabas, Zheng, 2010 page). Why?

First, China’s story is credible because it achieved three economic transformations and development goals within the timeframe of a generation. China and Africa, both started at low levels in the 1970s, are currently facing tremendous challenges. China is facing tremendous challenges domestically: labor productivity in agriculture is relatively low, decreased slightly in 2007 and remains about one-fifth of the level in other sectors; income inequality is worsening; the poor and vulnerable groups are quite broad; and there is a long way to go to achieve a balanced, equitable and sustainable development. That is, China and Africa are in the same boat.

Second, China’s approach facilitates experimentation on different crops and technology and is conducive to self-discovery. China has tried to combine aid, trade and investment which may be helpful to enhance capacity for self-reliance and self-development. This philosophyfollows the thousand year-old traditions of not only “offering fish” but

also “teaching how to fish.” Moreover, established donors have started to use innovative approaches to provide support along the entire value chain, including production, post-harvest storage, processing and marketing, as in the case of Feed the Future (US).

Third, China is learning from its own experiences, from African voices, and from established donors. As a responsible global partner,China is willing, and has started, to engage actively with the exis ting international aid community through dialogue, understanding, and cooperation (as shown by several trilateral co-operations involving FAO,IFC, WB, UK on agriculture). The multilateral cooperation between China and UNFAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) has achieved good results, laying a good foundation for more extensive bilateral and multilateral cooperation. (Li Xiaoyun 2010)