2011.04-Working Paper-The Synthesis of Grameen Bank, BRAC and ASA

The Synthesis of Grameen Bank, BRAC and ASA Microfinance Approaches in Bangladesh

—M. Wakilur Rahman , Xiaolin WANG , Salehuddin Ahmed , Jianchao LUO

Abstract

The paper describes the operational mechanism/institutional innovation of key Microfinance Service Providers (MSPs) in Bangladesh. Grameen Bank (GB), Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) and Association for Social Advancement (ASA) have been chosen to investigate the microfinance approaches. Selected MSPs are dominating microfinance market in Bangladesh in outreach, outstanding loans, savings and efficient service delivery mechanism. They offer micro-credit, savings and social services to the poor who were deprived from such access offered by conventional banks. However, they have distinct features with respect to group formation, service mechanism, product diversity and management systems. Grameen Bank, a special kind of Bank, offers loans to the poor particularly women in groups of five. BRAC is a private sector development organization providing financial and extensive social services to the poor in groups of thirty to forty. This group mechanism creates peer social pressure and solidarity, which seems to work well in a society where social networks are often of vital importance. Meanwhile, ASA as a full fledged microfinance institution offers individual loans groups consisting of 30-40 members in a group and the group co-liability is absent. GB, BRAC and ASA have been able to demonstrate the effectiveness of microfinance program towards sustainable development for the rural poor in Bangladesh. They have accomplished their effective and efficient management skills, innovative approaches and decentralized management systems. Meanwhile, microfinance clients particularly women have proven their talents for utilizing loans, maintaining regular repayment, credit discipline and the sincerity which have extended microfinance business scope in

a sustainable manner. The present study contributes to the literature on diverse microfinance approaches. The study may lead to further methodological improvement of the microfinance institutions in Bangladesh and elsewhere. Finally, microfinance practitioners and policy makers might gain better understanding on existing microfinance approaches in Bangladesh and can think or re-think for adaptation.

Keywords: Bangladesh, Microfinance approach, Grameen Bank, BRAC and ASA

1.Introduction

Bangladesh is the pioneer adopter of modern concept of microfinance in the world. The concept of microfinance is not only provision of microcredit but also the provision of savings, insurance, remittance, health, education, skill training and social awareness etc. According to United Nations definition, microfinance is loans, savings, insurances, transfer services and other financial products for low-income clients (UN, 2006). So, microfinance is

the financial and non-financial services to the poor who were traditionally not served by the conventional financial institutions. Noticeably, a huge number of Non-government Organizations (NGOs) and Microfinance Institutes (MFIs) have been promoting financial inclusion to the poor alongside government in the globe. Accordingly, financial and non-financial services have enhanced the inherent potentiality of the poor for entrepreneurship, income generation,

self-reliance, employment creation, increase wealth and at the end reducing poverty. More specifically, microfinance has been empowering the poor particularly the women in a society. Microfinance has served 150 million borrowers with 39 billion USD in loans and holding 22 billion USD in deposits from 67 million clients (MIX, 2010, Pacheco et al, 2010). Meanwhile, Microfinance Service Providers (MSPs) have developed and improved a good number of original methodologies and defied conventional wisdom to financing the poor with maintaining financial viability (Morduch 1999, CGAP, 2006). Encouragingly, Bangladesh has one of the largest, most innovative and best known NGO and MFI communities in the world (DFID, 2010). Hence, the country has achieved tremendous success in developing innovative micro-credit models, service diversification, financial sustainability and reaching microfinance to poor clients since inception in 1970s. For instance, GB, BRAC and ASA microfinance approaches are considered most successful approaches in the world. They are dominating microfinance market/sector in Bangladesh in outreach, outstanding loans, savings and efficient service mechanism. Until now GB (8.32 million), BRAC (8.45 million) and ASA (over 5.73 million) have extended services over 22 million out of 40 million microfinance clients (apart from overlapping) (MRA, 2010, Rashid et al. 2010). It is worth to mention, the approaches have crossed the national boundary and have been adapted by others with little modification according to suitability of the specific regional

environment. As recognition of their success, they have received several prestigious awards from national and international organizations. For instance, Grameen Bank and Prof. Dr. Mohammad Yunus jointly were awarded “Nobel Peace” prize in 2006 and Presidential award in 2010; Sir Fazle Hasan Abed founder of BRAC was awarded “Knighthood” by the government of United Kingdom in 2010 and the“Entrepreneur for the World”in 2009; Association for Social Advancement (ASA) was the winner of“Banking at the Bottom of the Pyramid” in 2008

by the Financial Times (London) and International Finance Corporation (IFC).

Nevertheless, microfinance approaches are not similar for GB, BRAC and ASA. However, it may be noted that

there has been learning and cross fertilization among three institutions. Grameen Bank is a special kind of Bank established to helping the poor who were denied from conventional banking system. BRAC is a private sector development organization providing financial and extensive social services to the poor while ASA is a full fledged microfinance institution assisting poor with financial and supplementary services. Accordingly, each and every microfinance service providers have distinct features with respect to group formation, service mechanism, product diversity and management systems etc.

The present study aims to critically synthesize the three approaches that are been practiced by GB, BRAC and ASA in Bangladesh. It is expected that the elaborate discussions on three approaches might help microfinance practitioners, experts, policy makers and service providers to understand the microfinance activities in a clear terms and re-think about future plans, strategies and actions.

2. Methodology

The study mostly relied on secondary sources of data. However, discussions were carried out with several microfinance experts to strengthen the quality of the paper. The paper is descriptive in nature paying special attention to comparative features.Secondary data were gathered from published articles, conference proceedings, annual

report, Microfinance Regulatory Authority (MRA) in Bangladesh, International Poverty Reduction Center in China (IPRCC) and the websites of GB, BRAC and ASA. Grameen Bank (GB), Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) and Association for Social Advancement (ASA) were selected for discussion on their microfinance approaches.

3. Why and how GB, BRAC and ASA Emerged?

Grameen Bank started in 1983. It is rooted in the action research arrived out in Jobra village (a village adjacent

to Chittagong University, Bangladesh) by Nobel Laureate, Dr. Mohammad Yunus in 1976. The action research was examining the possibility of designing a credit delivery system to provide banking services targeted at the rural poor. In that time, rural poor was denied from financial services by formal banks and mostly dependent on money lenders. Hence, the project was aimed to extend banking facilities to the poor women and men, eliminate the exploitation of the poor by money lenders, create opportunities for selfemployment, building organizations and forming reverse

dimension of poverty circle (i.e low income, injection of credit, investment, more income, more savings, more investment, and more income). The project’s success was implemented in other parts of the country with the

support of central bank of Bangladesh. Accordingly, the project was transformed into an independent bank by

government legislations in 1983. Today Grameen Bank is owned by the rural poor whom it serves. Borrowers of the Bank own 95% of its shares, while the remaining 5% is owned by the government (GB, 2010; Casuga, 2002). BRAC was started in early 1972 as a relief effort following the War of Liberation. In the War, a huge destruction (i.e human life, houses, roads, railway, bridge culverts etc.) were made by Pakistan army. Like other development organizations, BRAC was started to re-build the nation in close collaboration with the government. Accordingly, it became a community development organization providing health, family planning, education and economic support to different sectors of the rural community with particular emphasis on the most disadvantaged, such as women, fishermen

and the landless. So, BRAC evolved from a relief and rehabilitation organization to a development organization. In 1974, BRAC provided credit to the villagers in its Sulla Project in Sylhet district through the Sulla Thana Central Co-operative Association. In the following year, credit was advanced without interest to several landless groups. In 1976, BRAC started providing credit to landless through its Manikganj project. BRAC believes in the complexity and comprehensiveness of the poverty issue. It is a more empowering human resource approach to development. Poverty is not a microfinance issue only but a multidimensional issue needing multifaceted integrated approaches. Therefore, BRAC is not an MFI, it is a development organization. Thus, BRAC has always opted for the “credit plus- plus" approach, where loans are given to poor women in combination with establishing enterprises, health care

services, various forms of skill-training, non-formal primary education for children of BRAC members, social development and the creation of grassroots organizations for the poor (Halder, 2003). At present, BRAC has expanded microfinance services not only in Bangladesh but also served other developing countries in different parts of world.

From a similar background, ASA was established in 1978 to supporting the poor organize and empower themselves so that they could establish their political and social rights for a just society. ASA received formal registration from the government in 1979. In the beginning, ASA deliberately avoided lending arguing that loans would distract the rural poor from their fight for a just society. So, ASA programs were limited with awareness building, legal aid, training and communication support. Soon after ASA realized the importance of credit and it started social plus income generation activities. In this stage, empowerment was achieved through the improvement of health, nutrition, education, sanitation and by credit available to the poor. However, significant number of group

members left ASA and joined other NGOs. This aggravated situation inspired ASA to re-invent credit plus programs that eventually led ASA to be a full fledged microfinance institution. Accordingly, ASA has emerged as one of the largest and efficient Microfinance Institution (MFI) in the world.

4.Organizational Structure

The Grameen Bank is regulated by the government ordinance of 1983. This laid down a board of governors

composed of the chairperson, the managing director, and nine other members - five appointed by the government and four appointed by the borrowershareholders. Since 1986 to present, the bank has a thirteen member board of which nine are selected from the borrower-shareholders. The board approves the policies of the bank and serves as the link between the bank, the Ministry of Finance, the borrowers and other government organizations.

The Grameen Bank is a decentralized, pyramidal banking structure including lending units, centers, branch offices, area offices, zonal offices and a head office in Dhaka (Latifee, 2008). At the village level, solidarity groups are the basic lending units. In decentralizing process, the management functions and decision making powers have gradually been delegated to lower levels. The branch office is the lowest administrative unit of the Grameen Bank. In

fact, the zonal offices were added to the structures later on. Over the years, most of the functions of the head office have been transferred to zonal offices. The zonal offices delegate to the area offices the power of account supervision and loan approval. In this process of horizontal growth and decentralization of power, the head office becomes a secretariat or information clearing house. In order to encourage competition and achieve the objectives of sustainable operation and poverty alleviation, Grameen has introduced five star systems in its management. It examines both financial and social performance and leads the system to higher level growth. The 5 stars are green, blue, violet, brown and red. These are provided to branches and staff for 100 percent achievement of a special task. The green star is for 100% repayment, the blue is for earning profit, the violet is for self-financing, the brown is for all children in school and the red is for all the members moving out of poverty (Latifee, 2008).

BRAC governing body consists of sixteen members. Apart from the Chief Executive Officer, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, who is the founder chairperson of BRAC, all other members of the governing body are non-executives and executives (two members from executives). The governing body consists of highly distinguished professionals, activists and entrepreneurs who are elected by the general body and bring their diverse skills and experience to the governance of BRAC. The governing body is assisted by an audit committee which assists in reviewing the financial condition of the organization, the effectiveness of the internal control system of the organization, performance and findings of the internal and external auditors in order to recommend appropriate remedial action. There is an executive management body consisting of one Chief Executive Officer, one Adviser, two Executive Directors and three

Deputy Executive Directors and twelve Directors who oversee the overall management and implementation of programs (BRAC, 2010).

BRAC is also a decentralized organization with a strong management structure i.e head office, regional offices,

zonal offices or branches. The frontline members of the BRAC management are the Program Organizer (PO) who remains in the closest proximity of BRAC’s participants. A PO should cover 350-450 members through 12-15 VOs. Usually, BRAC has a main post that oversees the execution of its different core and support programs at Upozila (sub-district) level. All activities are carried out through branch offices (as well as the area offices). Generally, a branch office consists of 4-6 POs, one PO (Accounts cum computer data entry person), one PO in-charge. Area Manager at Upazila level is responsible for monitoring all programs including credit and other support programs. The

Area Manager sits in the office, which is situated in its own building. A regional manager is responsible for looking after the microfinance program of 13-15 Area Offices and their outpost.

ASA’s governing body consists of seven persons along with Chairman Mr. Shafiqul Haque Choudhury, the exofficio Secretary and founder & president. Governing body determines policy and budgets,manage resources, and set the rules for and monitor the field. The Chairman of the Governing Body plays a decisive mediating role. Generally founder president is playing vital role in the decision making process. However, ASA has adopted two-tier system of operation- the central office and the branch office in the field. Branch offices can be considered as center of activities. Branch offices are independent cost and profit centers. All activities of ASA branches can be done and approved by the branch office itself, as long as it confirms to the ceilings identified by the working manual. The working manual changes each year to keep up with all relevant changes. Each branch has one Branch Manager (BM), one Assistant Branch Manager (ABM) and 4 Loan Officers (LO) on average. Branch offices do not have accountants or cashiers. Loan officers are responsible for maintaining daily accounts and rotate to perform the job of cashier. Branch accounting and transactional accounts are maintained by the Branch Manager. The LO is responsible for overseeing between 18 and 24 groups comprising of 360-550 members. Each district has a team of Regional Managers (RMs) headed by a District Manager (DM). The district office is in a centrally located branch of the district town/city with an extra desk for each of the district officials including the District Manager (DM), Assistant District Manager (ADM). Regional Managers (RM) sit in the different geographically important branches. RMs, ADMs and DMs supervise and monitor all field level activities. The central office consists of Human Resource (HR), Operation, Finance & Management Information System (MIS) Section, Accounts Section, Audit Section, Research and Documentation Section and IT. The President of ASA directs the personnel of different sections.

5.Ownerships Status

There is an ongoing debate on the ownership pattern of the microfinance organizations throughout the world. In

fact, most of the microfinance organizations are (NGOs) private by nature and the general feature of such organizations is not for profit. So, they cannot distribute the profits. On the other hand, if someone owns the organization, they will make profit and provide better service as well. But, due to profit orientation, they may charge high interest rate for loan and thus the poor will be the ultimate victims. BRAC and ASA are registered as a non-political, non-partisan not-for-profit Societies under the Societies Registration Act 1860 (Act No.XXI/1860) . While, GB is completely distinct as it is know as special kind of Bank. Grameen Bank is own by poor people. The people that the bank provides credit to, become the shareholders of the bank and own the bank. Each member purchases one Grameen Bank share worth Taka 100 (US$1.50). These shares provide a stake in the ownership of the Grameen Bank for the membership as well as their representation in its board of directors. Over time, both proportion of members' share in total capital and the representation have increased. At present, GB’s clients own 95 percent

ownership and only 5% own by government.

6.Outreach of GB, BRAC and ASA

Microfinance outreach refers to the ability of MSP to provide financial and non-financial access to a large numbers of borrowers who had previously been denied this access. However, the question is - can microfinance

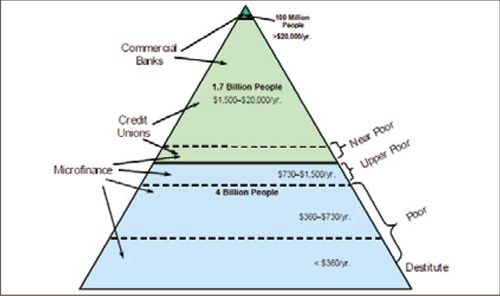

reach to the large number of very poor people by maintaining sustainability? There are two different arguments, first- theoretically microfinance targets all the poor clients but in practice it often fails to reach those living in extreme poverty (Rahman and Razzaque, 2000; Halder et al, 1998; Hashemi, 1997). Second, ‘yes’ microfinance can reach to the bottom of the poor at least a certain level (Prahalad, 2010; Dunford, 2006; Halder, 2003). Figure-1 shows the distribution of outreach in different financial intermediaries (adopted from C.K Prahalad’s Book, “The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid”). The numbers of people and their annual per capita expenditures are taken from VISA International and The World Bank. The commercial banks have traditionally, and mostly still do, reach only the top of the pyramid. Credit unions, especially those based on community rather than workplace, have done better in reaching further down the pyramid through their cooperative principles and lower cost structures, but even they do not generally reach below the international poverty line. Surprisingly, innovations of microfinance have made it commercially feasible to reach further down. It is generally agreed that financially sustainable microfinance operations reach the “near poor” and the “upper poor”. What about the bottom of the poor those living on a dollar a day or less? Incredibly, GB, BRAC and ASA have reached to the “very poor” people particularly the women through their special credit programs. For instance, Grameen Bank struggling members program exclusively for the beggars which has extended services over 112,216 beggars. Similarly, BRAC has reached 1.17 million ultra poor through Challenging the Frontiers of Poverty Reduction (CFPR) program (BRAC, 2009) while ASA has extended services to 4754 hard core poor with it special credit program (BRAC, 2009; ASA, 2009).

In general, microfinance outreach has expanded remarkably in Bangladesh overtime with respect to number of clients especially the women and geographical coverage. For example, Grameen Bank has extended services to 83,458 villages, with 2564 branch offices spread across country, serving 8.32 million borrowers (cumulative no. end of July 2010). Similarly, BRAC and ASA have extended services to 70000 villages (plus 2000 slums) and 70,066 villages, with 3028 and 3236 branch offices spread all over the country, serving 8.45 million and 5.73 million clients

respectively (cumulative no. end of July, 2010). It is noted that the percentage of active women borrowers for the three institutions, GB, BRAC and ASA, are 97, 98 and 88 percent respectively, which is an indicator of their commitment to empowering women. In Bangladesh, women’s mobility and their interaction with men other than immediate family members were restricted in the past. The cultural attitudes restrict women’s mobility to go to the market, leaving them dependent on men to put their income-generating skills and knowledge into practice in terms of income generation from their assets (Holmes and Jones, 2010). Accordingly, rural women are placed in a vulnerable position since employment opportunities are limited and lack health care services, receive less nutrition, and are less educated than their male counterparts. In addition, there is growing number of female-headed households due to divorce, death of the male earner, and desertion and male migration. In contrast, it is regarded that women are

the best care taker of the future generation, efficient to utilize tiny amount of money and good repays as well. Realizing the issues, GB, BRAC and ASA (ASA has micro-credit program for male) focuses mainly on rural women, bringing about meaningful transformation in their lives by making small loans available to them for income generating activities. MSPs also provide other non-financial services i.e education, health, livelihood development training and legal aid ensuring empowerment of women in the society. Accordingly, MSPs have discovered doing

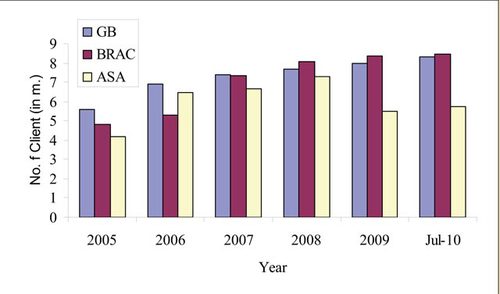

business with poor particularly with women is not only profitable but also less risky. The Figure-2 shows the number of clients of GB, BRAC and ASA overtime, which has shown the sustainability of MSPs with expanding client horizon.

Figure 1 Outreach of different financial intermediaries in pyramid

Figure 2 No.of clients of GB, BRAC and ASA during 2005 to July 2010

7.Product Diversity of GB, BRAC and ASA

The concept of microfinance does not limit within microcredit rather it consists of micro-credit and plusplus. In Bangladesh, Microfinance Service Providers (MSPs) often provide financial (credit, savings, insurance, remittance etc.) and non-financial (nonformal schooling for disadvantaged children or community-delivered health care, training, legal aid and social awareness) services. Interestingly, there is a hidden competition among MSPs to innovate new

products and services in a comprehensive manner suiting to poor people livelihoods. GB, BRAC and ASA have experience in all kind of microfinance services. They are offering some common services, i.e micro-credit, savings, micro-insurance and education. Meanwhile, they have subdivided loan and saving products targeting different socio-economic strata. Beside some common services, there are some specialties in their products and services. For

instance, BRAC has extensive program in education, health, human rights, legal services, agricultural, training, social enterprise, research and extension. BRAC is also maintaining the whole supply chain -both upstream and downstream -that maximizes benefits to the poor (Spainhower, 2010). Taking an example from BRAC dairy and food project, the project provides a market for BRAC's village organization members. Members take loans to buy cows. They receive training on proper care and maintenance of the livestock. BRAC ensures forward linkage through buying milk from these women at a fair price and providing artificial insemination and livestock feed which ensure backward linkage as well.

Similarly, GB has special services for beggars, education schemes for member’s children and social business. Grameen-Danone Yogurt (Shoktidoi) Factory is a good example for social business. One cup of

yogurt provides 30 per cent of the recommended daily intake of nutrition. Mothers are keen to buy the yogurt for their children. Going ahead, Grameen's initiatives in textiles (the setting up of a textile factory), in agriculture and fisheries (the Krishi and Motso Foundations), in solar and wind energy (Grameen Shakti), and in telecommunications indicate that Grameen Bank has innovative products to improve the situation of the bottom poor. On the other hand, ASA has adopted diversified loan products, savings and insurance as a specialized microfinance institute. Key products and services of GB, BRAC and ASA are- GB offers credit, savings, insurance, education, health, training, remittance and social business. BRAC offers credit, savings, insurance, education, health, training, social development, legal aid services program, research and development, human rights and advocacy, public affairs and communications, human resource development and so on. ASA is a purely MFI, offers credit, saving, insurance and education products. The following section provides details of some core products and services.

8.Operational Mechanism

Several microfinance models/approaches have developed in different countries and serve clients with diverse socio-cultural backgrounds. However, Bangladeshi microfinance approaches are extremely successful and well known. GB, BRAC and ASA have made successes in their own approaches. Like other microfinance service providers, GB, BRAC and ASA were established to provide financial and other supportive services to the poor. But, their operational mechanism and service delivery system is quite distinct from each other.

The basic features of GB model are: i) poor people’s access to credit with women as a priority by forming small solidarity groups (5 members); ii) GB’s goes to the door steps of the clients instead clients coming to office; iii) does not require any collateral; iv) small loans repaid in weekly installments (there are some loan products which accept monthly repayment); and v) eligibility for higher loan amount for succeeding loans (GB, 2010). Generally, when a person wants to borrow money from the bank, she/he is asked to form a group of five people. It is not an easy process to form a group of five like-minded friends. This is to ensure group solidarity. After the formation of a group, the bank discusses the rules and procedures of the Grameen Bank. The group is told that the bank would not extend

loans to the five at the same time. In the first stage, only two of them are eligible for, and receive, a loan. Only if the first two borrowers begin to repay the principals plus interest over six weeks, do the other members of the group become eligible for a loan (GB, 2010). The group is asked to make sure that the money is used rightly and repayment is made in due time. In this way group support among the members is built up and a member of the group not only becomes responsible to oneself but also to the group as a whole.

Usually, eight groups constitute a center, while 30-60 centers represent a branch. Each center elects a chief

from the groups’ chairpersons. Group members are required to attend weekly center meetings conducted by the center chief who oversees applications for new loans as well as payment of loan installments. The bank worker/loan officer attends all meetings, participates in the discussions, and disburses and receives money. Thus banking is conducted openly in front of all members, and members take active roles in discussions on progress and problems. In each village, there may be one or two centers. Centers are responsible for banking transactions and other social functions as well. In the process of doing that, they have come up with something that is popularly known in Grameen Bank as "sixteen decisions" (no dowry, education for children, sanitary latrine, planting trees, eating vegetables to

combat night-blindness among children, arranging clean drinking water, etc.). Mostly, these "decisions" deal with social issues.

When the Grameen Bank decides to open a branch, the first task of the branch manager is to prepare a socioeconomic report covering the geography, economy, demography, transport and communication infrastructure, and political power structure, of the area to be covered by the branch. Once the head office approves the report, the branch manager then organizes a public gathering of all sections of people in the locality. The Grameen Bank's rules, programs and purpose are explained there. Also, at that meeting the bank officials are introduced. It is only after that the bank's operation begins in that locality.

BRAC forms group consist 30-40 people is known as Village Organization (VO). VO is an association of poor, landless people that come together with the assistance of BRAC and try to improve their socio-economic positions. In fact, VO is a platform for launching and implementing BRAC’s various activities. More importantly, VO serve as forum where the poor can collectively address the principal structural and social impediments to their development, receive credit, and open savings accounts and build on their social capital. The main goal of VO is to strengthen the capacity of the poor for sustainable development and enable the poor to participate in the national development process. Even, it uses VO members as a pressure group for overdue collection from the default members of the VO.

Messages from the organization are communicated to the groups through VO leaders. Along with group approach, BRAC is also adept in individual approach for providing credit facilities. BRAC’s microfinance staff meets VOs once a week to discuss and facilitate credit operations. The social development staff and health staff meet VO members twice a month and once a month respectively to discuss various socio-economic, legal and health issues. Credit decisions are taken in weekly VO meetings. BRAC considers three things before considering a loan application: the member’s capacity to utilize the loan money, types of business, profitability of the Income Generating Activity (IGA)/business. Formal loan proposal is prepared by the respective program organizer (PO) then the accountant checks and verifies savings and credit records of the applicant by using a computer. The loan proposal is forwarded to the manager at the same office for verification and approval by the manager. At the branch office, the accountant

disburses the loan after the manager interviews the borrower (Husain, 2007). BRAC’s main principles of microfinance program are- make credit available to poor women, especially in rural areas; provide credit at a reasonable price; involve poor women in income generating activities through credit provision; promote the economic development of the country by increasing the income level of the rural poor; operate self-sustaining credit activities. The lending mechanism is not rigid one, thus BRAC is still refining this holistic "credit plus" approach. Actually, microfinance is only are of the several components of BRAC’s Development approach. BRAC works through the VO in mobilizing, organizing all aspects their comprehensive approach to development and poverty alleviation.

On the other hand, ASA approach is slightly distinct from GB and BRAC approaches. ASA group consists of 30-40 people. ASA approach is known as sustainable and cost-effective microfinance model. The approach has proved effective in making a branch self-reliant within 12 months. Any MFI that adopts this model for operations becomes sustainable within the shortest possible t ime . The ditinct features of ASA’s operational mechanism are:

◎ Branch offices have no accountants. Accounting and cash-handling is simplified, distributed between

the branch manager and the three or four loan officers, and then subjected to a tight schedule of repeated monitoring by senior staff at four different levels stretching up to head office. Nor do they have guards: male staff lives on the branch premises.

◎ Each branch prepares its own annual work plan with fiscal targets and cash flow projection. After money

comes in from daily collections (savings, insurance premiums and loan installments), the branch calculates how much it needs for daily accounts or expenditures and then deposits the rest in to the bank. The branch office can draw money whenever required. Even, money may also come from other branches in the district, depending on their surplus.

◎Districts and regions have no support staff and no separate offices of their own. District and regional managers is supervisory staff who shares a building and services with one or more branches.

◎ There is no training. No training cell, no training centre, no trainers. Work routines are standardized and

simplified so that new recruits need only a few days of supervised work experience in a branch before being sending off to another one to start work. Head office staffs are given no in-service training. Head office thinks, develops strategies and procedures sends manuals and instructions to the field.

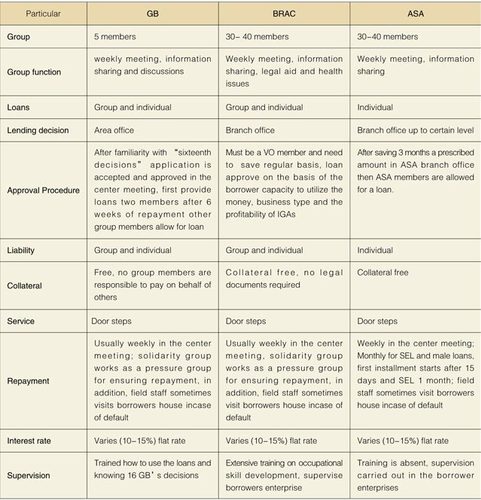

Table 1 Key Features of GB, BRAC and ASA

9 .S e r v i c e D e l i v e r y Mechanism of the Major Products

There are four major kinds of financial services offered by Bangladeshi MSPs. These are loans, savings, death

benefits or insurances and remittances. Bangladeshi MSPs (i.e GB, BRAC and ASA) realizes that since the poor do not constitute a homogenous group, one-sizefit- all type of an approach with microfinance will not be suitable for all categories of the poor. Thus, they have introduced different financial intervention according to the needs of different people living at different poverty levels. The following section discusses different products and services one by one i.e loan products, saving products, insurances, remittances, education and health.

10.Financial intermediaries/services

10.1 Loan Products

Micro-credit is the basic product for microfinance activities. Hence, there are several sub-divisions within micro-credit product. GB, BRAC and ASA have adopted seven, three and five kinds of micro-credit products respectively. As mentioned in previous section, every MSP has developed new products according to different segment of people and is distinct from each other. Thus, the discussion is started from loan products.

10.1.1 GB loan products

GB’s loan program includes basic loan, housing loan, higher education loan for member’s children, micro

enterprise loan, loan for village phone, business loan for graduate students of Grameen member families and

loans for struggling members.

Basic loan: Generally, basic loan is offered for one year term but there is flexibility from 3 months to 3 years. The

basic loan which includes all income generating loan activities constitutes about 98 percent of the total loan portfolio. This loan follows general lending methods of GB. The loan amount ranges from BTK 1000 to 5000. The interest rate is 10 percent (flat ).

Housing loan for the poor: Grameen Bank found that the poor needed to pay annually Tk 300-2000 (US$ 4-30)

for repair of their thatched roofs. In fact, the house is not only the shelter but also a place for income generating such as a store, a shop or a home factory for the poor. Responding to the needs of the poor, GB introduced housing loan in 1984. It became a very attractive program for the borrowers. Maximum amount given for housing loan is Tk 15,000 (US $ 218) to be repaid over a period of 10 years in weekly installments. Interest rate is 8 per cent. A total amount of Tk 8.95 billion (US $ 210.38 million) has been disbursed for housing loans end of July 2010.

Micro-enterprise loans: Many borrowers are moving ahead in businesses faster than others for many favorable reasons, such as, proximity to the market, presence of experienced male members in the family, etc. Grameen Bank provides larger loans, called microenterprise loans, for these fast moving members. There is no restriction on the loan size. A total of Tk 72.77 billion (US$ 1080.26 million) has been disbursed under this category of loans (end of July 2010). Average loan size is Tk 26,976 (US $ 388.49), maximum loan taken so far is Tk 1.6 million (US $ 23,209). This was used in purchasing a truck which is operated by the husband of a borrower. Power-tiller, irrigation pump, transport vehicle, and river-craft for transportation and fishing are popular items for micro-enterprise loans.

Education Loans: Students who succeed in reaching the tertiary level of education are given higher education

loans, covering tuition, maintenance and other school expenses. By August 2010, 46,487 students received

higher education loans, of them 44,152 students are studying at various universities; 485 are studying in medical schools, 787 are studying to become engineers, 1063 are in other professional institutions. Interest rate for education loan is 5% and is charged after graduation.

Loan for village phone: To-date Grameen Bank has provided loans to 391,422 borrowers to buy mobile phones

and offer telecommunication services in nearly half of the villages of Bangladesh where this service never existed

before. Telephone-ladies play an important role in the telecommunication sector of the country, and also in

generating revenue for Grameen Phone, the largest mobile telephone company in the country.

Loan for beggars: The struggling members program of GB is a very special program. It is an example of

deepening financial inclusion and GB’s commitment to social development. The objective of the program is to

provide financial services to the beggars to help them find a dignified livelihood send their children to schools

and graduate into becoming regular GB’s members. More than 112,216 beggars have joined this program and many of them already left begging. Basic features of the struggling members program are- they make up their own rules, all loans are interest–free, loans can be for very long term, to make repayment installments very small, inclusion of life insurance and loan insurance programs without paying any cost, groups and centers are encouraged to become patrons of the beggar members, struggling members are not required to give up begging, but are encouraged to take up additional income-generating activities like selling popular consumer items from door to door, or at the place of begging.

10.1.2 BRAC loan products

IGVGD: Income Generation for Vulnerable Group Development (IGVGD) program covers the poorest women who own no land, have little or no income, or are widowed or divorced. The objective of the IGVGD program is to alleviate poverty of the hardcore poor by providing long-term sustainable income and employment opportunities through food assistance, training and access to credit facilities. In fact, the program is known as Challenging the Frontiers of Poverty Reduction (CFPR) which was initiated in 2002. In December 2009, 272,000 women received

a productive asset transfer worth between 8,000 and 13,000 taka (between $112.94 and $183.54). In addition to the transfer, CRPR provides intensive training and support in managing the assets; a daily stipend until income is generated from the assets (approximately 300 taka ($4.24) per month for approximately 18 months); subsidized health and legal services; social development training; water and sanitation; and the development of supportive community networks through Village Poverty Reduction Committees (Holmes and Jones, 2010). The empirical study found (Das and Farzana, 2010; Shina et. al. 2008; Halder, 2003) the special investment program of CFPR had positive impact on productive use of development funds for the benefit of ultra poor households in Bangladesh. Challenging the Frontiers of Poverty Reduction provides an innovative example of an asset transfer program.

DABI: DABI members are those who own up to one acre of land (including homestead) and sell their manual

labor to earn their living. Any BRAC village organization member is eligible for DABI loan. Major types of credit

under the DABI programs include General Loans, Housing Loans and Disaster Loans. General Loans: ranges from Tk. 4,000 – Tk. 50,000 (US$ 50 – 500) with a flat 15% interest rate. Loans are payable over one year through 46 weekly installments. The clients and their representatives at the centre perform most of the roles and responsibilities with facilitation by the staff of BRAC at the branch. Housing Loan: One of the effects of having facilities for safe drinking water is the enhanced buying capacity that helps members participates in other types of credit also. This credit is similar to sanitation credit for the customers. The credit size is up to Tk. 10,000 payable over one year through 46 weekly installments at a flat interest rate of 10%. Disaster Loan: Disaster credit is given to those customers who are affected by natural disasters and have used credit from the organization. The disaster credit helps the customer contain economic erosion due to disaster. Credit amount is depending on the need. The loan is granted for one year term and the repayment method settles at the time of credit disbursement. Even, the interest rate is also determined according to the need assessment.

PROGOTI (Microenterprise Loan): Started in 1996, this program aims generate income and create new

employment through enterprise development in the rural and semi-urban areas of Bangladesh. This is achieved

by providing credit facilities and technical assistance to new and existing small businesses. PROGOTI borrowers

are required to open a bank account in order to receive the loan. Loan sizes range from Tk. 50,000 - 500,000

(US$ 700 to 7,000) with an interest rate of 15% flat and monthly repayment.

10.1.3 ASA Loan products

Small loan for female clients: This loan is accounted for 78% of total loan portfolio. Economically active poor to

undertake or strengthen income generating activities are eligible for this loan. The loan ranges from BDT 10,000-

20,000 (US$ 150-300) depending on the economic potential of area and client’s capacity as well. It offers weekly repayment having 15% interest rate (flat). Second term loan increases depending on success of the previous loan.

Hardcore poor Loan: This loan is accounted for 1% of total loan portfolio. A flexible loan product for hardcore/

ultra poor has initiated matching their irregular pattern of income generating activities. However, maximum loan size is only 5000 (US$75). Loan is granted for 4-12 months. Repayment is very flexible (monthly, quarterly and half-yearly installments or at a time) settled at the time of disbursement. Second term loan increases depending on success of the previous loan.

Small Business loan: The loan is accounted 12% of total loan portfolio. A loan product is disbursed to informal or formal micro enterprises to promote production/enhance business activity and employment generation. Maximum

loan size is BDT 50,000 or (US$ 735). Loan is granted for 1 year and repayment made on weekly or monthly basis.

Small Entrepreneur Lending (SEL): The loan is accounted for 6.5% of total loan portfolio. Loan product is initiated for informal or formal small/micro enterprises to promote production/enhance business activity and employment generation. This product also caters to information technology related activities. Maximum loan size is BDT 700,000 (US$ 10,226). This loan is granted for 1-2 years having 15% flat interest rate. Repayment is made on monthly basis.

Agri-business Loan: This loan is accounted for 1.5% of total loan portfolio. A loan product for supporting agribusiness related activities. The maximum loan size is BDT 350,000 or US$ 5,113. The loan repayment, loan

term and interest rates are similar to SEL.

Rehabilitation Loan: A loan product for clients’affected by natural disasters e.g., flood, cyclone etc. Maximum loan size is BDT 2,000 or US$ 30. This loan is interest free and the repayment is made on weekly or monthly basis. Loan is granted for 12 months.

Education Loan: A loan product to support clients’ children studying in 8th grade and above. Maximum loan size is BDT 5000 (US$ 75). Repayment is made on weekly basis having 15% flat interest rate. Loan is granted for 12 months.

10.2 Saving Products

Saving is a part of income not consumed immediately in favor of the future. At present, saving is an important

part of the microfinance activities. Hence, the selected MSPs offer several saving options for its clients and non-clients.

GB has different kinds of savings products. These arecompulsory saving: within compulsory savings there

are sub-divisions i.e emergency fund- contribution is BDTk 5 per 1000 lent, children welfare fund- members

required to pay BDTk 1 per week. The children’s welfare fund provides education for members’ children in schools managed and run by GB groups (Hasan and Guerrero, 1997). Grameen Pension Savings: this scheme for GB members and staff; personal savings and double in 7 years-term deposits: its open to all; loan insurance savings: only for GB members; Fixed Deposit with monthly income: open to all. By the end of August, 2010 total deposit in Grameen Bank stood at Tk. 93.89 billion (US$ 1352.11 million). Member deposit constituted 53 per cent of the total deposits. Balance of member deposits have increased at a monthly average rate of 2.66 percent during the last 12 month (June 2009 to July 2010). The deposit rate varies from 8.5 per cent to 12 per cent.

Similarly, BRAC offers three kinds of savings- Compulsory Savings: when members take loans, it is mandatory to deposit 5% of the loan amount into their savings account. The interest rate for the savings is 6%. Normally borrowers can withdraw their savings anytime. Own Savings: members are required to save a minimum of BDTk 5 (US$0.071) per week. Current Account Savings: BRAC has recently introduced current account savings that bear no interest but allow the group members to make unlimited withdrawals.

ASA also offers three kinds of savings- mandatory savings: clients belonging to basic loan category except

SEL and Agri Business loan are required to deposit a fixed amount minimum deposit rate in BDT 10 (US$ 0.15). Clients can withdraw anytime but need to keep 5% equivalent of loan (principal) as balance. Interest rate on savings is re-arranged in every year on the basis of bank rate. Voluntary Savings: The term and conditions are similar to mandatory savings. But, it is optional for clients. Long Term Savings: any client can participate in this product. This is monthly an installment based deposit with fixed return usually higher than regular savings but close to fixed rate of return. Minimum deposit rate is BDTk 50/ 100/ 200/ 300/ 400/ 500 per month. Deposit term is 5 and 10 years. The deposit rate is 9% for 5 years duration while it is 12% for 10 years duration at maturity. Clients can withdraw any time

before maturity but with lower rate of return.

10.3 Insurance Products

Microfinance service providers are gradually becoming interested in offering insurance products. MSPs over

the years have offered various kinds of insurance products like health insurance, life insurance, credit insurance, property insurance and crop insurance but have experienced difficulties in attracting clients and maintaining the sustainability of the product (MIFA, 2009). Grameen Bank introduced one of the earliest insurance products in the sector, including health insurance through Grameen Kalyan. In case of death of a GB’s borrower, all outstanding loans are paid off under loan insurance program. Under this program, an insurance fund is created by the interest generated in a savings account created by deposits of the borrowers made for loan insurance purpose, at the time of receiving loans. Coverage of the loan insurance program has also been extended to the husbands with additional deposits in the loan insurance deposit account. A borrower can get the outstanding amount of loan paid off by insurance if her husband dies. She can continue to borrow as if she has paid off the loan. The families of the deceased borrowers are not be required to pay off their debt burden any more, because the insured borrowers or

their insured husbands do not leave behind any debt burden to take care of. Life Insurance: Borrowers are not

required to pay any premium for this life insurance. Each family receives BDTk 1,500 (US$21.5). A total of 128,818

borrowers died so far in Grameen Bank. Their families collectively received a total amount of Tk 227.34 million

(US$ 4.54 million).

Similar to GB, BRAC has introduced a death benefit policy for its VO members beginning in 1990. BRAC

partnered with the market leader in insurance, namely Delta Insurance to offer life insurance. The product offers TK 10000 (US$ 150) to the family in case of death of a member to cover funeral expenses and contribute to the repayment of remaining liabilities. Members do not have to pay a regular premium for the life insurance facility. The key features of BRAC’s insurance policy are- any poor woman when she becomes a VO member is eligible for this benefit. BRAC’s insurance service provides Tk.10,000 (US$150) to the dependants of the deceased, no premium is charged to the members. BRAC pays the money to the family from the interest earned through its credit program.

ASA has not lagged behind to offer insurance to its clients. ASA has four kinds of insurance benefits. Loan

Insurance: Any client can participate in this product; an installment based deposit with fixed return usually higher than regular savings but close to fixed rate of return. Premium is in each loan cycle BDTk 10 (US$.15) per thousand loan disbursement. Non-refundable but in case of death of borrower or borrower’s spouse, the total outstanding loan is written off. Member’s Security Fund (Mini Life Insurance): All basic loan clients must contribute and participate in this product. Premium is BDTk.10 (US$ 0.15) per week but BDTk 10 (US$ 0.15) per month for Hardcore Poor Loan. Refundable with 4% interest but 6 times the amount of balance paid in case of eight years maturity. Male Member’s Security Fund (Mini Life Insurance): Spouse or family head of female clients’may participate in this product. Premium rate is similar to member’s security fund BDTk 10 (US$ 0.15) per week. Refundable with 2% interest but 3 times the amount of balance paid for four years term.

10.4 Remittance

In order to serve migrant workers and their families abroad, Bangladeshi MSPs are now offering money transfer services in collaboration with commercial banks and money transfer companies such as Western Union. BRAC is involved in remittance transfer process. BRAC Bank Ltd has agreement with Western Union for remittance transfers in Bangladesh. BRAC Bank is using the microfinance network of BRAC for transferring remittances in the rural areas. It is easy for BRAC to provide remittance services through its large networks. At first BRAC enlists migrant worker families through survey and register their names who are interested to receive their remittance through BRAC and BRAC Bank. The registration fee is Tk.100 (US$1.5). Once the formalities are finished, the receiver is requested to inform the sender(s) to remit through Western Union through BRAC Bank. Similarly, ASA has started foreign remittance with National Bank Limited jointly since July 2008 with a view to facilitating increased remittance inflow through the banking channel to Bangladesh. More than 700 branches have been brought under remittance service until December 2009 (ASA, 2009).

There are some other MSPs, BURO Bangladesh and Thengamara Mahila Sabuj Sangha (TMSS) have been

involved in countrywide internal money transfer (INAFI, 2007). However, GB has yet not started remittance services. Grameen Bank, had sought permission from Bangladesh Bank for taking part in remittance transfer and utilization. Bangladesh Bank was favorably disposed to this idea but till now it is under consideration to amend GB’s ordinance in the parliament Non- Financial Services (Siddiqui, 2004).

10.5 Training Products

Training is considered the key instrument towards successful microfinance interventions. Hence, GB and BRAC have been providing training services while ASA has no such services. Grameen Bank pays high priority to educating and training its bank personnel and borrowers. The goal of the training is to build committed bank employees who work in accordance with the bank’s philosophy. Prospective branch managers are trained for six months--five months extensive fieldwork practice in a branch office, and 4 weeks inclass study. Trainees learn about banking procedures such as loan processing, deposit-banking, record keeping, and accounts maintenance. This exercise orients the bank worker to the poverty of rural life and how the poor perceive the bank (MacIsaac and Wahid,

1993). Meanwhile, group of borrowers participate in a training of at least seven days to learn about the GB’s philosophy, banking rules and procedures, business skills, the responsibilities of the group chairperson, “Sixteen Decisions” and the group savings program. They are also taught about health, children’s education, other social development programs, and how to sign their names (Hossain, 1993). After participating training program each group attends weekly meetings. When the group demonstrates familiarity with the rules and regulations, formal status is granted. Loans are given to two members first after successful repayment (following two months) other group member are allowed for loans (Jansen and James, 1998). The training program of GB is focused on loan procedures and rules primarily.

BRAC has adopted extensive training activities not only for its staff and clients but also for outsiders. The BRAC Training Division (BTD) is responsible for capacity building and professional development of BRAC staff and program participants through a wide range of training and exposure initiatives. Leadership, management skills development and occupational skills for microfinance program participants are also remarkable. The broad objective of BRAC training is the enhancement of knowledge, skills and attitudes of the program participants and staff as well as other external development practitioners working within and outside Bangladesh. A well-known feature of BRAC training is its participatory nature, which is learner-centered, problem focused and need-oriented. It promotes

individual involvement in the training process and group interaction. The training courses are designed and delivered from the perspective of the participants’needs. The courses are continuously upgraded to meet

the evolving needs of the BRAC programs. At present there are 21Training and Resource Centers (TARCs), three rented training centers and two BRAC Centers for Development Management (BCDMs) that operate year-round training courses facilitated by experienced trainers. Some of the training programs and courses are - In house training, vocational training, training for the community leader. The training courses include- Gender awareness and analysis; gender and social change; gender and reproductive health; gender and HIV/AIDS; gender and rights.

Surprisingly, ASA does not have any kind of training programs. So, it has no training cell, no training center and no trainers. Work routines are standardized and simplified so that new recruits need only a few days of supervised work experience in a branch before being sent off to another one to start work. Head office staff is given no in-service training.

10.6 Education Products

Bangladesh government has provided free education for girls (up to grade 12) and boys (up to grade 5). However, greater portions are unable to complete their education as they are either forced to drop out in order to seek employment to supplement household income, or drop out because they do not have the sufficient support to perform (Rahman, 2010; Hasan and Guerrero, 1997). Concerning the issue, MSPs came forward by establishing schools and supplementary services. Accordingly, GB encourages borrowers to establish schools, pre-schools and day-care services to tutor members’children while they are engaged in their business activities. Furthermore, GB school system also provides member families with a full program of elementary education. Meanwhile, BRAC

has accomplished education program for children different groups of people. These includenon-formal primary education programs for traditionally outside formal schooling, support to formal schools, education for ethnic children and education for adolescents (no. of adolescent center is 8,868). Even, there is an option for higher education (BRAC University). BRAC’s has 2195 rural community based libraries (Gonokendras), of which about 1085 are equipped with computers that are connected to the Internet and 8,016 Kishori Kendras that give members access to a variety of reading materials (Brac annual report, 2009). On the other hand, ASA has education loan program for clients’ children and higher education institute (ASA University).

10.7 Health Products

A few MSPs have included health support programs to ensure the wellbeing of clients and their families. Among others GB and BRAC are notable ones. At the very beginning, ASA also had health program for its clients. BRAC has very extensive health programs. From its founding days, healthcare interventions have been an integral aspect of BRAC’s holistic and rights based approach. The two major objectives of the BRAC health program are to improve maternal, neonatal and child health, and to reduce vulnerability to communicable diseases and common ailments. The health program is a combination of preventive, curative, rehabilitative and promotional health services that have proven effective in the past. Building on the experience of past successes, the health program has evolved and responded to emerge national health problems and scaled up former pilot projects. It engages 80,000 Community Health Volunteers called Shastho Shebikas who are members of the VO, trained to provide health education, sell essential health commodities, treat basic ailments, collect basic health information and refer patients to health centers when necessary (Gain, 2010). BRAC comprehensive health care program reaches to 14.5 million people. Tuberculosis (TB) control program reaches 88.5 million people (Brac annual report, 2009). About 4 million pregnant women have received antinatal care from BRAC. BRAC provided essential health services include- health and nutrition education; water, sanitation and Hygiene (WASH); family planning; immunization; pregnancy-related care; basic curative services; and tuberculosis control. Taking an example of WASH program, BRAC started Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) program in 2006 in partnership with the government. Program goal is to provide sustainable and integrated WASH services in the rural areas and break the contamination cycle of unsanitary latrines, contaminated water and unsafe hygiene practices, as well as ensure sustainability and scaling-up of WASH services. In this program number of latrines installed or repaired were 5 million and the participants in the cluster meeting was 61.5 million (Brac annual report, 2009). In some areas, it includes additional activities such as services for presbyopia, pneumonia, malaria and promotion of safe delivery practices. It also collaborates with national programs such as Vitamin-A supplementation and family planning.

Beside above mentioned products and services there are other several products including family planning

and welfare, agriculture and related activities, water supply and sanitation, human rights and advocacy, legal aid, women entrepreneur development, research and evaluation division (only BRAC has independent research cell) and so on.

11.Financial Strength

Bangladeshi MSPs are most self-sufficient in Asia particularly the larger ones. They are financially sustainable because, they can accumulate funds from diverse sources i.e, local banks, wholesale fund from Polli Kormo Shyakak Foundation (PKSF), international donor grants, savings/deposit of members, interest or service charges. Hence, ASA was the first MSP to attract loans at market rates of interest from commercial banks (Agroni and Sonali Bank). In fact, PKSF has been playing a greater role to making MSP financially selfsufficient. As an apex institution, PKSF has been working as both financial intermediary and market developer and continues to be an institution central in the Bangladeshi microfinance landscape (Bedson, 2009). PKSF was established in 1991 by the Government of Bangladesh for refinancing the NGOs providing micro-credit services to the poor in rural areas. PKSF was refinanced by government funds as well as funds from the World Bank to continue to meet the growing financing needs of the sector. Accordingly, most of the large MSPs have established their scale of operations and achieved

financial self-sufficiency through their collaboration with PKSF. It is regarded that PKSF is part of the success of MSP giants such as ASA and small MSPs (MIRB, 2009). PKSF has helped various small MSPs to achieve high levels of operational efficiency whereby they can enhance their financial self-sufficiency and leverage funds from the commercial banking sector in future. However, over the years, external donor grants have declined in a significant pace (from 30.4% in 1997 to 7.9% in 2005). It is worth to mention that the declining donor grant does not affect the microfinance sector as much. For instance, GB and ASA do not accept any grants or donations from outside sources since 1998 and 2001 respectively but they are enjoying financial self-sufficiency status. While BRAC has increased

73% self-sufficiency and only 27 depends on donor grants. However, these grants are only for children’s education, right based services and health programs. No grants are now taken for microfinance activities. Microfinance in BRAC is self financed (Santen, 2009).

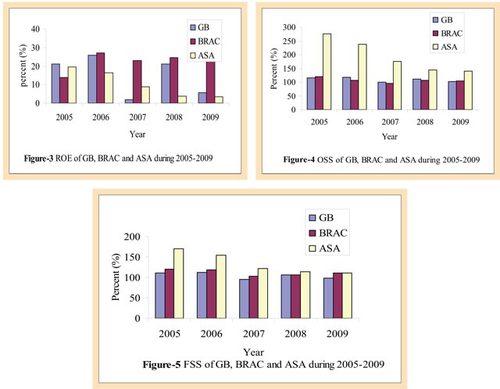

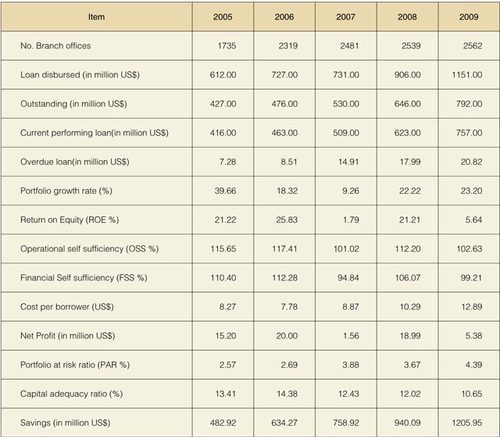

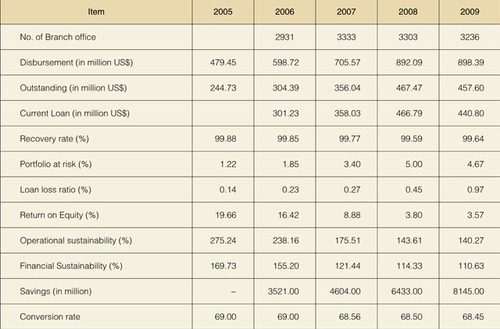

Nevertheless, the financial strength of Grameen Bank, BRAC and ASA have been assessed on the basis of

Return on Equity (ROE), Operational Self-sufficiency (OSS) and Financial Self-sufficiency (FSS) overtime (see annex 2 & 3 for more details). Operational Selfsufficiency refers to the ability of the institutions to generate enough revenue to cover its operating costs while Financial Self-Sufficiency (FSS) refers to the institution's dependence (or lack of it) on subsidies for successful operation (Murdoch Dec 1999). Table 2 reveals that Return on Equity was 5.64%, 4.73%

3.57% for GB, BRAC and ASA respectively in 2009. The Operational Self-Sufficiency was 102.6%, 105% and 140.27% for GB, BRAC and ASA respectively. Meanwhile, Financial Self-Sufficiency for GB (99.21%), BRAC (111.48%) and ASA (110.63%) which is definitely indicate their financial strength. Following three figures (Fig-3, Fig-4 and Fig-5) shows the ROE, OSS and FSS of GB, BRAC and ASA last five years. It appears from figure(s) ROE, OSS and FSS have significantly contributed towards sustainability of GB, BRAC and ASA’s microfinance program.

12.Regulatory Status

Some kind of regulation is necessary as microfinance sector grows rapidly and deals with money and more importantly poor people’s money. Usually, it is the government role to promulgate regulations for microfinance sector as government is responsible to keep safe citizen right and their money. However, many MSPs have developed a code of conduct that imposed self-regulation on them. Whatever the form of regulation, there should be a concrete regulation which can ensure the interest of the poor and the organizations as well. Realizing the matter, over 50 countries have implemented or are considering specific arrangements for regulation and supervision of microfinance either as a separate law or as amendments to the existing legal and regulatory framework in world (Mohanty, 2010). Accordingly, Bangladesh is moving toward building concrete microfinance regulations by a separated regulatory authority.

Nevertheless, the establishment of separate regulatory authority was not an easy task as Bangladesh MSPs

were mostly self-regulated. Hence, MSPs have enjoyed lots of freedom working with government or individually

for rebuilding the nation. Actually, Bangladesh evolved as an independent nation in 1971 after 9 moths of Independence War. In this war, a huge destruction was made and several intellectuals and scholars were killed

by Pakistani army. The government received donor grants to re-build the nation. Accordingly, government and non-government organizations worked hand in hand to restoring livelihoods of the people through income generating activities (MIRB, 2009). Initially the government and individual social leaders (later NGO) embarked on relief and rehabilitation works. Gradually the NGOs earned a space and the government created a space for NGOs to take part in nation building programs. That is how the NGOs became more development organization. NGO-MFIs have

vastly widened their activities as social and economic empowerment of the poor.

With the rapid expansion of NGO-MFIs activities and increasing inflow of external resources, the government

was concerned with transparency and accountability. Responding to the need, government created the NGO Affairs Bureau (NGOAB) in 1991. NGOAB’s activity spectra entails the areas like- NGO registration, approval of project proposals, releasing funds and monitoring NGO projects, etc. NGOAB played the role of the primary regulator of the development NGO-MFIs supported by foreign funds, providing microfinance services in the country. In real sense,

MSPs remained “unregulated” until established Microcredit Regulatory Authority Act 2006 with the initiative of Bangladesh Bank (the central Bank of Bangladesh) after extensiveconsultation with NGO and bank leaders. MRA’s responsibilities are to provide/ cancel licenses and monitor MFIs performance for strengthening a sustainable financial market. The minimum criteria of obtaining license are- either minimum balance of outstanding loan at field level BDTk four million or minimum borrower 1,000. The act emerged after reviewing several previous Acts including

Societies Registration Act 1860 (the same as in India), Cooperative Credit Society Act 1904, Companies Act 1913, Trusts Act 1882, Charitable and Religious Trust Act 1920 and Cooperative Societies Ordinance 1984 (MIRB, 2009). According to MRA recent report there are 503 NGO-MFIs been registered/ licensed out of 4240 applied for. The remaining MSPs are under review process for registration. MRA held an international conference on Microfinance Regulations: Who benefits? during 16-17 March, 2010 to have world experience regarding microfinance regulations (MRA, 2010). In addition, MRA has conducted another participatory conference among MSPs for settling most debatable issue i. e. interest rate and deposit collection (MRA, 2010, Khan, 2010). Recently, MRA has announced a

guideline for NGO and MFIs in a circular issue on 10 November, 2010. The key guidelines are:

◎ The maximum effective interest on loans must be 27 percent

◎ MSPs must pay at least 6 percent interest on mandatory weekly savings of borrowers

◎ NGO-MFIs can be charged maximum Tk 15 for loan application forms, client admission fee, passbooks, etc.

◎ No deduction of money from loans should be allowed at the time of loan issuance, in the name of savings, insurance, or any other category.

◎ For micro-enterprise loans, the stamps fee must be Tk 50

◎ Mandatory to allow at least a 15-day gap between the dates of loan issuance and first repayment inst allment ,negotiations between lender sand borrowers, for a longer gap, have been allowed

◎ Mandatory to allow at least 50 weeks time for recovering entire amounts of general loans which are issued for a period of one year

◎ MSP must calculate rates of interest on loans in declining balance method, in place of the existing flat rate method

◎ MSP must have a specific pay structure, which must be sent to the authorities.

It is noted that GB, BRAC and ASA have registered from MRA along with other NGO-MFIs. In addition, they have

adopted self-regulatory mechanism in their respective organizations.

13.Reasons for Successes

a. Lending Mechanism: The group lending with individual responsibility mechanism is often presented as the key factor of MSPs success .Hence,GB, BRAC and ASA have continuously improved their group lending approaches overtime. At present, they are providing individual loans along-with group lending.

b. Responsible borrowers: Combination of joint liability is considered as vital to high repayment rates. But,

this is not only the reason of joint liability but also hard working of the field officers and responsible borrowers particularly the women. Hence, poor has proven to be better repays. It is because of people’s sincerity, honesty, hard works and responsible behavior.

c. Learning from women: MSPs are good listener of poor voice especially women. Accordingly, MSPs have designed and re-designed several innovative products after listening from women.

d. Trust: Most of the MSPs had started their activities as effective distribution of relief funds in cash and kinds. It

is regarded that MSPs are more efficient in respect to service delivery to the rural community. Hence, MSPs have achieved certain degree of faith to the community or society. For example, BRAC community development programs i.e health, education, social awareness has contributed a lot and satisfied people’s mind. So, the MSPs have been using their past trust for expanding their existing programs in a successful manner.

e. Women active participation: Women have proven their entrepreneurship and business skills for utilizing and repaying loans. By doing so, they are contributing toward changing existing social system (male dominant society) in Bangladesh. Meanwhile, their active participation in microfinance activities has extended the business opportunity of MSPs.

f. Demand push: The people are really poor with many needs in Bangladesh. Hence, loans are very need

oriented towards improvement of their livelihood.

g. Collateral: Collateral free and simple loan approval process of MSPs (GB, BRAC and ASA) has triggered

the success. In Bangladesh, formal financial institutes are inefficient and less popular due to their complex procedures, collateral requirement, favoritism to better off people and claim for bribes. More importantly, the NGO type MFIs offer services to the door steps of the clients while formal banks offer services from their offices which might be a good reason for greater participation in microfinance program.

h. Group formation: Bangladesh is most densely populated (1046 person per square km.) country in the

world. Each and every village consist huge number of population. Usually, there is a negligible heterogeneity within a village. Hence, forming a solidarity group is difficult but not as much in Bangladesh. MSP conveys the vision and mission to the villagers and may start their microfinance activities without any severe difficulties.

i. Product diversification: MSPs are allowed to offer diverse products and services (savings, insurance,

remittance, social development etc.) particularly the savings/deposit has contributed to improve the economies of scale.

j. Fund availability: Bangladeshi MSPs have received significant amount of donor grants and soft loans which

improve their scale of business. Meanwhile, Bangladesh Bank and commercial banks are offering soft loans

to the MSPs. In addition, PKSF is working closely with MSPs by providing financial and technical assistance. So, the combination of this supportive environment facilitated financial self-sufficiency of a good number of MSPs.

k .Attitude to repayloan: The high successful repayment rate by the borrowers have attracted financial intermediaries. They have seen business i.e microfinance.

l. Friendly relation between borrowers and loan officers: Microfinance is a loan program with a human face. It is

a relationship building between the borrowers and the staff/organization. Accordingly, microfinance sector has realized the importance of human relationship and is trying to maintain it in a meaningful way.

m. Positive relation between government and MSPs: MSPs have earned government faith with their hard works, proper systems and commitment to improving people’s livelihood especially the women. Thus,government has less intervened microfinance market which leveled to rapid growth of this sector in Bangladesh.

n. Decentralization: Strong decentralization combined with extensive information and communication system

is also a reason for success. The specific organizational structure makes good management and transparency of

GB, BRAC and ASA.

14.Learning/lesson from GB, BRAC and ASA

The most remarkable lesson can be learned from GB, BRAC and ASA’s microfinance approaches that the

organization can work so successfully in the villages even in slum areas of the poorest countries in the world.

It is regarded that a poor country (like Bangladesh) can develop its own way to poverty alleviation. Some specific

learning points are:

◎ Credit access to poor is a very important and vital part of any social and economic development of the poor. Definitely, innovation of collateral free group lending by GB, BRAC and further development by ASA others have shown success in Bangladesh and some other parts in the world.

◎ MSPs have reached the poor very productively and with a sense of concern and belief in the strengths of the

poor especially women.

◎ The credit plus-plus approach has benefited more and has considered more applicable towards poverty

alleviation.

◎ It is proven by GB, BRAC and ASA that poor can utilize loans and repay them if effective procedures and

relationships are maintained and established.

◎ Decentralize organizational pattern of GB and BRAC combined with extensive information and communication systems are lessons for other development partners/ organizations.

◎ In Bangladesh, there is a competition among microfinance service providers particularly key players so products keep improving. In addition, government has also several collaborative programs in certain direction towards poverty reduction. The government has gained full points for poverty reduction with proper policies and guidelines.

◎ The service delivery mechanism of GB, BRAC and ASA can be applied to other developing countries with adaptation.

◎ Microfinance is not simple. It needs professionalism, systems, dedicated works and a comprehensive approach building relations with the people.

◎ People have performed in their respective role to make the microfinance sector successful.

15.Future Challenges

In Bangladesh, significant successes have been achieved by large MSPs in respect to innovative approaches, diversified products and services, financial strengths and improving regulatory environment. However, the microfinance sector is not out of future challenges. Some of them are-

◎ Beside success of large MSPs, a vast majority small MSPs are not able to move efficiently towards commercialization, due to lack of adequate human, financial and technical resources.

◎ MSPs always used higher repayment as indicator of success. However, there is obligation that loan officers

may use their superior status to pressure clients to pay the weekly meetings, sometimes using techniques that come close to social collateral.

◎ It is regarded that microfinance is an effective tool towards poverty alleviation. However, the question remains whether such an approach is comprehensive to poverty alleviation if there is limited connection in production, infrastructure and market development process.

◎ It is not an easy task to determine the impact of poverty alleviation of such microfinance programs

in Bangladesh. In fact, simultaneous programs have been implemented by government and other development partners. So, it is the combination impact of th development intervention by MSPs, development organization and government.

◎ Despite supervisory mechanism (provide enterprise skill trainings and guidance for utilizing loans) for disbursing loans, there is concern about unproductive use of loans.

◎ About 3000 MSPs have been operating in Bangladesh at local, regional and national level. These micro-credit suppliers provide credit without taking care of previous lending history (whether she receives loans from other

MFIs or not). Thus, there is a concerning trend of multiloans of borrowers which fell them difficulties to repay and create over-indebtness.

◎ Despite flexible initiative in recent years, there remains concern of exclusion of the poorest and remote areas in Bangladesh. It is reported by PKSF that the coverage of micro-credit operations is absent in the more remote and less populous districts of the country’s north and southwest part.

Criticisms are good as long as they are constructive. Leading to further improvement of approaches of adapted.

16.Applicability