2012.04-Working Paper-The Decoupling of Economic Growth, Agricultural Growth and Poverty

The Decoupling of Economic Growth, Agricultural Growth and Poverty Reduction in Tanzania: Lessons from China1

Li Xiaoyun, Wang Haimin and Paolo Zacchi

Abstract

Between 1998 and 2008, Tanzania almost doubled its annual GDP growth while also achieving a higher agricultural growth rate; however, the national poverty headcount fell by just 2.1% during the same period. It is apparent that the high economic growth and even greater agricultural growth witnessed in Tanzania has hardly affected poverty. In contrast, China has employed an agricultural development-led pro-growth model, which has contributed to significant poverty reduction. This paper concluded that the isolated growth patterns of the economy and the agricultural sector likely contributed to the decoupling of growth and poverty reduction in Tanzania.

Keywords: Tanzania, China, growth, agriculture, poverty reduction

1. Introduction

Despite its poor performance during the 1990s, the annual GDP growth of Tanzania almost doubled over the last decade from 4.1% in 1998 to 7.4% in 2008 (Tanzania Poverty and Human Development Report, 2009). At the same time, the country’s agricultural GDP was reported to have grown by 4.4% between 1998 and 2008 (MAFSC, 2008). Tanzania’s high economic growth has hardly affected poverty, however, between 2000 and 2007, the national poverty headcount fell by only 2.1% (from 35.7% in 2000/2001 to 33.6% in 2007), with an equally modest decline in rural and urban areas (Hoogeveen, 2009). Over a longer time span, food poverty dropped from 21.6% in 1991/92 to 16.6% in 2007/08 – a reduction of just 5% in 15 years - while basic needs poverty showed a similarly slight decrease (from 38.6% to 33.6%) during the same period (Tanzania Poverty and Human Development Report, 2009). Given high population growth of around 3% per year, these modest reductions in poverty levels in fact represent an increase in the absolute number of Tanzanians living under the poverty line (around one million during 2001-07).

Tanzania’s poverty-growth elasticity reached 0.76 during the 2001-07 period, meaning that 1% of growth could only bring about a 0.76% decline in poverty. Not only has the income poverty and nutritional status of households not improved substantially, but the share of the population with insufficient calorie consumption declined only marginally from 25.0% to 23.5% during 2001-07 (World Bank, 2009). These meagre outcomes raise concerns about why rapid economic growth has not been translated into much greater improvements in poverty reduction. The weak poverty-growth elasticity and inconsistency among growth, poverty and nutrition trends underline the decoupling of growth and poverty reduction (Pauw et al., 2010).

In contrast to the Tanzanian experience, China’s rapid economic growth since 1978 has always been closely associated with poverty reduction. The consumption poverty incidence (as measured by the World Bank’s US$ 1.25 PPP) has fallen from about 84% in 1981 to 15.6% in 2005 (Chen et al., 2008), while the annual poverty rate has dropped by about 5.7% over the last few decades. Based on China’s national income poverty line, poverty-growth elasticity has remained around 2.7% from the 1980s until the year 2008 (Li, 2010a). Every 1% of economic growth has led to an almost 2.7% decrease in the incidence of possible reasons of the decoupling between poverty in China over the last 30 years, which makes China’s growth model uniquely pro-poor. It is therefore useful to understand why China’s growth has led to rapid poverty reduction while Tanzania’s has not. This article analyzes the growth and poverty reduction in Tanzania with reference to China’s pro-poor growth model in order to suggest ways in which the former might be able achieve its goal of becoming a middleincome country by 2025.

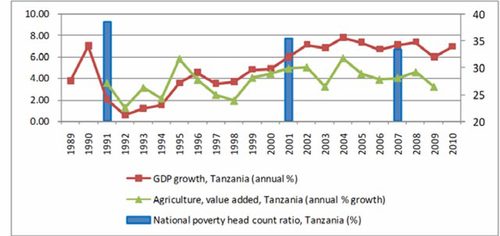

2. Growth, poverty reduction and population dynamics in Tanzania and China

This section compares data showed in Figure 1 and Figure 2 with data from China for the period 1978-84 and data from Tanzania for 1998-2008, coinciding with the most significant phases of economic growth in these countries’ recent histories. Tanzania’s annual GDP growth almost doubled during this period (from 4.1% in 1998 to 7.4% in 2008), with an annual average of around 7%, while agriculture GDP growth increased at an average rate of 4.4%2 (Figure 1). Nevertheless, with 2.9% population growth during the same period, Tanzania only managed about 4.1% net per capita growth and 1.5% net per capita agricultural growth.

Figure 1 Annual GDP growth rate, annual agricultural growth rate and poverty headcount ratio at national poverty line, Tanzania (mainland)

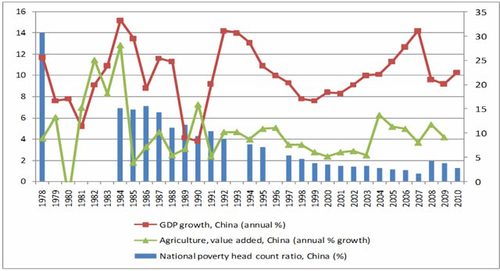

China’s GDP growth per annum increased from11.7% in 1978 to 13.5% in 1984, while agriculture grew from 4.1% in 1978 to 12.9% in 1984 at an average rate of 8% (Huang, 2008). The rural poverty incidence, measured according to China’s national poverty line, declined from 30.7% in 1978 to 15.1% in 1984, representing a reduction of almost 50% in rural poverty, while farmer income increased annually by 16.5% (Huang, 2008). The poverty-agricultural sector growth elasticity in China was 2.7% after the 1980s and remained at 1.5% from 2000 to 2008 (Li, 2010b), which is much higher than the 0.75% recorded in Tanzania for the period 2001-07.

Many factors explain these different development outcomes. Population growth is certainly the part of the story; with an increase of just 1% at the time, China created much higher net agriculture growth (Figure 2) than Tanzania (7% and 1.5% respectively). Assuming that Tanzania can maintain its current 7% economic growth and reaches its target of 5% agricultural growth, with the current rate of population increase Tanzania would only achieve a 2.1% per capita agricultural growth rate, which is much lower than the 7% growth recorded in China. Indeed, Tanzania’s higher agricultural labour growth rate of 3.8% suggests that the country needs both much higher economic and agricultural growth in order to offset rapid population growth and produce a surplus to stimulate effective growth.

Figure 2 Annual GDP growth rate, annual agricultural growth rate and poverty headcount ratio at

national absolute poverty line in China

Source: NBS, China.

Note: the poverty line was readjusted in 2008 from 785 CNY to 1196 CNY. No official data are available for the years 1979-83 and 1993-96.

3. The importance of economic structure and growth patterns for poverty reduction

In addition to the effects of population growth, the different growth patterns followed by China and Tanzania largely explain the relationships between growth and poverty in these two countries. Although poverty could theoretically be reduced through either pro-poor growth or the distribution of benefits from overall growth, growth is clearly more effective for poverty reduction when it is propoor. For the latter to occur, the sector that employs the majority of the poor should make a significant contribution to growth. China’s remarkable poverty reduction was accompanied by high economic and agricultural growth, particularly at the per capita level. Employing the national poverty standard, the incidence of rural poverty dropped from 30.7% in 1978 to 15.1% in 1984 and to just 2.8% in 2010. About 50% of the rural poor were out of poverty during 1978-84.

This period experienced the highest economic and agricultural growth and the most rapid poverty reduction ever witnessed in China. The agricultural sector contributed significantly to the GDP growth rate accounting for 35% during this time.

Although industry in China grew rapidly and contributed to a large percentage of the entire economic growth rate, a substantial part of the industrial growth rate originated from agriculture. Agriculture has provided labour force and raw materials for agriculture-based rural enterprises that indirectly contributed to industrial growth. The contribution of total production value from rural enterprises to total industrial production value expanded from less than 9.1% in 1979 to 20% in 1985, and farmer net income increased 132% during these six years (Huang, 2008). This broadbased growth pattern confirms that countries where the rural population is dominant, such as China and Tanzania, must focus on effective agricultural growth and whole economic transformation to reduce poverty. This has also been the case for countries such as Vietnam and, to some extent, Indonesia (OECD, 2010).

In the period of analysis, Tanzania experienced a high average economic growth of 7%, leaping from 4.1% in 1998 to 7.4% in 2008, along with incipient structural change that was accompanied by only a small change in poverty (MFEA, 2009). The agricultural growth rate, however, averaged just 4.4% and contributed only 16% of the total economic growth rate during 2001-08 (Table 1), which was much lower than the 35% contribution that China’s agricultural growth rate made during its period of highest economic growth.

Table 1 Average growth rate and growth contribution by main economic sectors, Tanzania(2001-2008)

Source: Government of Tanzania and Authors' calculations.

Although overall growth rates after 2001 were much higher than in the 1990s, from 1986 to the end of 1990s agriculture in Tanzania only grew from 3.3% to 4%, which shows a weak relationship between economic growth and agricultural development (World Bank, 2000). Over the past 10 years, the country’s agricultural sector, which employs more than 75% of the total labour force, has not grown enough to contribute to the overall growth rate, providing just 35% of new jobs (World Bank, 2009). Usually, economic structural transformation can lead poverty

reduction, for instance in China, the provinces exhibiting slow changes in economic structure usually had a lower poverty reduction rate (World Bank, 2001). Agriculture’s share in GDP in Tanzania only declined from about 29% in 1998 to 24% in 2008 (MFEA, 2009), and the decline has not been accompanied by agricultural productivity improvement.

The growth in agriculture in Tanzania is substantially limited by its forward and backward linkages. Lack of agricultural supplies, food processing capacity, transport bottlenecks in both short and long range traffic and other rural services make it difficult for agriculture to grow rapidly, even without the additional challenges posed by population growth. At the same time, the country’s economy is dominated by the services sector, which accounts for more than 45% of GDP. Since 2000, the sector has grown at an annual average of 7.6%, which is higher than agricultural growth and close to the level of overall economic growth. With the exception of tourism, however, the services sector has not created significant employment for low-skilled labour. The largest growth in employment outside agriculture from 2001 to 2006 has been in public administration and other services (530,000 jobs), while the sector likely employs low skilled labour such as trade, restaurants and hotels only created 20,000 jobs. Overall, the pattern of growth has not created significant employment opportunities for rural people, either directly in agriculture or indirectly as rural migrants.

The industrial sector’s contribution to GDP has grown slowly from 25.2% in 1998 to 28.2% in 2008. Mining has been the most dynamic subsector, expanding rapidly at an average annual growth rate of 15% between 2000 and 2007. However, the links between the mining sector and local supply chains that could create employment opportunities have been weak (MFEA, 2009). Manufacturing has experienced very limited

growth (from 8.4% in 1998 to 9.4% in 2008), which is insufficient to create a large number of jobs. The construction sector also grew and might have contributed to employment; however, its small scale in comparison with the overall economy has been an obstacle in this regard.

Those sectors with a high growth rate, such as the rapidly growing service sector (7.6% annually), have not contributed to a substantial reduction in poverty levels, because sub-sectors like communications, which are not labour-intensive and employ no low-skilled workers, also failed to generate sufficient employment opportunities for the poor. Even those sectors that provided employment to low-skilled workers, such as tourism and construction, which have been among the most dynamic, have not significantly affected poverty because their share of the overall economy remained relatively small.

Thus, the sectors that exhibited higher growth rates during the recent period of rapid economic growth in Tanzania happened to be those that were unable to generate significant employment for the rural population. In contrast, the growth of the agricultural sector, which employs a large part of the labour force, was largely offset by increases in population and the number of available rural labour force.

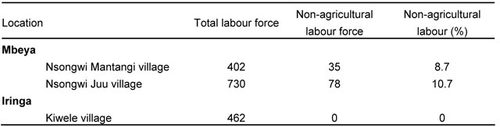

Over the last 10 years, Tanzania has created employment for an average of 630,000 people per year, but employment has been primarily in small informal businesses, which typically have low earnings and productivity (MFEA, 2009). For the urban youth, 45% of new jobs were in unpaid family work (World Bank, 2009). A rapid field study by the authors in Mbeya, Iringa, and Morogoro indicates that significant rural-urban migration has not occurred over the last 10 years (Table 2). The farmers interviewed said that they could earn about TSH 40,000 per month in the city, but there was nothing left to save. The poverty assessment for the country shows that the slight income growth for the rural poor had a large effect on overall poverty in Tanzania. The movement of households out of agriculture has also played a major role in poverty reduction; acceleration of national poverty reduction can be achieved only through an accelerated decline in poverty in rural areas (Hoogeveen et al., 2009).

Table 2 Non-agricultural labour in three villages in Mbeya and Iringa, Tanzania

Source: Field visits, 2010.

It is clear that between 1978 and 1984, China’s rapid economic growth was largely based on agriculture and agriculture-related sectors, while national poverty reduction was predicated on poverty reduction in rural areas. In contrast, Tanzania’s relatively high economic growth from 1998 to 2008 was obviously disconnected from agricultural growth, and poverty reduction in urban areas such as Dar es Salaam had only a limited effect on national poverty reduction due to the relatively small size of the urban population. This leads one to question whether the efforts made by the Tanzanian Government to reduce poverty during the last decades were on the right track, and whether the plan to develop agriculture as an engine of growth and economic development was effective.

In addition to the factors mentioned above, China and Tanzania began their periods of rapid economic growth with different level of income distributions, which also affected poverty reduction efforts. When Tanzania’s economy began to grow rapidly after 2000, its Gini coefficient was already 0.35. This provided Tanzania with much less space for rapid growth than had been had by China, which had a Gini coefficient of about 0.1 at the end of the 1970s. Positively, however, the inequality in Tanzania remained unchanged over the last seven years, with its Gini coefficient

remaining at 0.35 during 2000-07 (MFAE, 2009), which provides a good basis for the country’s future growth. This is reflected in the fact that despite the much larger increase in inequality in Dar es Salaam, poor households here gained more income than in other areas where the increase in inequality was more modest (Hoogeveen et al.,2009).

4. Agricultural structure and growth patterns also matter

No country in the world has succeeded in developing an economy with a large agricultural population without first developing its agricultural sector. Although agriculture cannot be relied upon to develop the entire economy and bring about structural transformation, it is nonetheless essential to focus on agricultural development for a time, ideally at the beginning of a country’s economic takeoff. To develop the agricultural sector, particularly smallholder-based agriculture like that found in China and Tanzania, growth patterns affecting agricultural development and poverty reduction must firstly be given attention to.

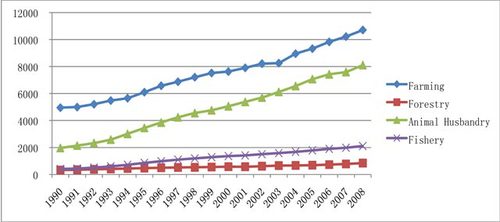

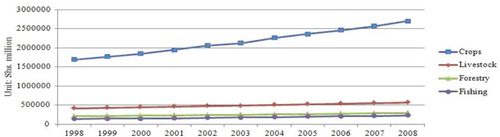

Seventy-four percent of Chinese farmers are engaged in farming and livestock production; food crops have long been the major focus of smallholders, with rearing livestock an important secondary livelihood. Fishing is also a source of income for farmers, while forestry is mainly undertaken by the state. The total value of crop production is much higher than that of livestock, fishing and forestry (Figure 3). Within the agricultural sector, the value of crops and livestock has grown much more than other sub-sectors over the last 30 years.

Figure 3 Production value of cropping, forestry, livestock and fishery in China (at constant 1990

price, unit: 100 million CNY)

Note: by definition in national statistics of China, the agricultural sector comprises cropping, forestry, livestock and fishery subsectors.

Source: Calculated based on data from NBS, China.

In Tanzania, farmers mainly engage in crop production and livestock rearing; forestry and fishing are usually managed by large corporations, although the latter is often the primary livelihood for people in coastal and lake areas. Thirty-seven percent of households in Tanzania keep livestock. The value of crop production in Tanzania far exceeds that of livestock, forestry and fishing (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Gross domestic products by types of economic activity in Tanzania (at constant 2001 prices)

Source: NBS, Tanzania.

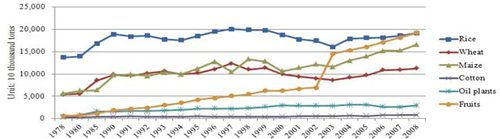

In the context of crop production, rice and wheat are the most important sub-sectors for Chinese farmers, with rice found mainly in southern parts of the country and wheat grown mostly in the north. Cotton is only grown in northern areas of China, while maize is produced in relative small quantities throughout the country. Large-scale crop production is dominated by rural family farms, as the planting area available on large state farms is limited.

Over the last few decades, particularly after the 1978-84 period, the output of rice, wheat and maize has expanded significantly in China (Figure5). Among the major food crops, rice grew by 4.5%, wheat 8.2%, maize 2.2%, annually during1978-84 and both were major drivers of the increase in food crop production in China. Rice production, too, increased significantly, though not to the same degree as wheat. The growth of both wheat and rice has implications for household income because both were grown widely by the rural poor during the 1978-84 period. Cash crop production also increased, with cotton and oil seeds growing at 11.4% and 20.3% respectively; this had a high poverty impact, though this was limited by the crops’ narrow geographical distribution. During 1978-84, fruit production grew at 10% with wide distribution across the country, though the benefits were mainly accrued by relatively wealthy farmers (Table 3). During the China’s rapid economic growth period, agricultural growth was broad-based but driven by different sub-sectors, which led to differential effect on poverty. Wheat and rice were central in linking the growth of food crop production with poverty reduction.

Figure 5 Output of rice, wheat, maize, cotton, oil plants and fruit in China during 1978-2008

Source: NBS, China.

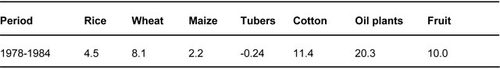

Table 3 Average annual growth rate of main crops in China (%)

Source: Author’s calculations, based on NBS, China

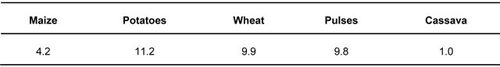

Between 1998 and 2008, food crop production in Tanzania increased at an average of around 4% per year. During this period, cassava was the largest contributor to production quantities (32%), followed by maize (18%), potatoes (17%), bananas (16%), paddy (6%) and pulses (5%) (MAFC, 2008). It should be noted that more than half of the total harvested area in Tanzania is allocated to cereals, of which maize is the country’s dominant staple food crop (Pauw et al. 2010).

Maize production accounted for 36% of the total food crop planting area and involved over 80% of Tanzanian farmers, whereas wheat was produced almost exclusively by large-scale commercial farms in the Northern Zone. Rice was becoming an important crop for smallholders in the Western and Lake Zones (Pauw et al., 2010), but comprised a smaller percentage of production quantities and planting area. During 1998-2008, the production of all food crops had expanded, but at different rates. The highest growing sub-sectors were potatoes, wheat and pulses, while farming of cassava and maize grew more slowly (Table 4).

Table 4 Production trends: Average annual growth in food crop production in Tanzania (%)

Source: MAFC, 2008

From 1998 to 2008, the main drivers of growth in food crop production were potatoes, wheat and pulses. A similarly high rate of growth was seen for all major cash crops, including cotton (11%), sugar and tobacco (9%) and cashew (7%) (MAFC, 2008). These crops are highly concentrated in specific regions, however; both cotton and tobacco are smallholder crops (but limited in some regions), while sugar is mostly produced by large-scale commercial farmers (Pauw et al., 2010). With this growth pattern, the sub-sectors that include a majority of smallholders have been largely excluded from high growth. Thus, the growth of crop production benefits certain regions or groups at the expense of the others, namely, the smallholders who make up the majority of Tanzania’s population.

Above all, during the initial stage of economic growth in China in 1978-84, agricultural growth and particularly the output value of crop production were highly favourable for smallholders. The country’s high economic growth rate was accompanied by high growth rates for agriculture, food crop production, particularly wheat, rice along with a high rate of poverty reduction. Tanzania has maintained an economic growth rate of more than 6% since 2000; however, poverty reduction has not exceeded 2% during this period. The economic growth rate has not been accompanied by the necessary growth rate for agriculture, crop production and dominant crops such as maize. Indeed, the sectors that grew rapidly did not result in effective employment increases, and the agricultural sub-sectors that expanded did not benefit the smallholders who comprise the majority of the country’s population. Therefore, the country’s low poverty-growth elasticity can be regarded primarily as a result of the current structure of agricultural growth, which favours large-scale production of rice, wheat and traditional crops as opposed to crops whose production would benefit the largest number of smallholders, such as maize and cassava (Pauw et al., 2010).

5. Importance of structural changes

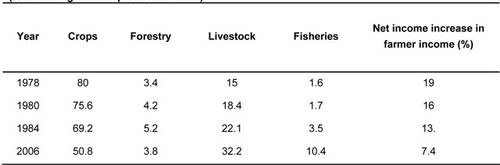

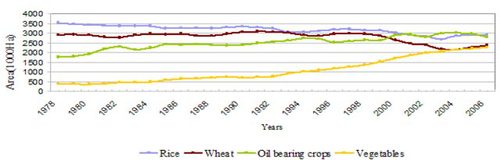

Sustained pro-poor growth requires continuous structural transformation. China’s rapid poverty reduction has followed three steps of structural changes that provide a powerful engine for continuous poverty reduction over time. First, during 1978-84, China experienced rapid increases in production of food crops, cash crops and livestock. The system of agriculture began to change from one centred on only food crops to one focused on food crops, cash crops and livestock production. The share of crop production value in total agricultural production value dropped from 80% in 1978 to 69% in 1985, while livestock increased from 15% in 1978 to 22% in 1985. Within crop production, cotton, oil seeds, sugar, vegetables and fruit all experienced a rapid increase in planting area and yield. Food crop production increases mainly from productivity increases and not from area expansion. The period 1978-85 experienced the highest growth rate in farmer income in real terms (Table 5 and Figure 6).

Table 5 Changes in agricultural structure in China, 1978-2006 (% of total agriculture production value)

Source: Song (2008: 209)

Figure 6 Changes in planting area for rice, wheat, oil-bearing crops and vegetables in China, 1978-2006

Source: Author's calculation, based on FAO, 2009.

Second, from 1984 to 1988, the area available for production of non-food crops continued to expand, and this was accompanied by productivity improvements for major staple crops. Third, after 1984, the entire rural economy began to be transformed. Rural township enterprises became engines for economic growth, attracting 146 million labourers from the surrounding areas, while farmer income from rural enterprises increased from 11 CNY per capita in 1984 (8.2% of farmer income) to 1666 CNY in 2006 (46%). Indeed, in recent years, such enterprises have become the major source of farmer income in rural China(Song, 2008).

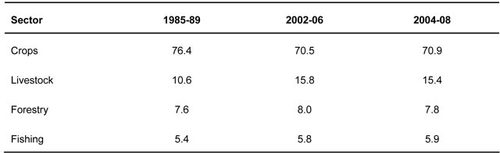

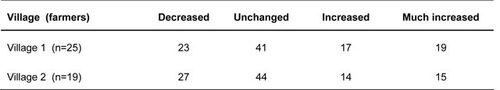

Between 1985 and 2008, Tanzanian agriculture did not undergo a significant transformation despite the incipient economic structural changes introduced during the second half of this period. The contribution of crops to total production value has not changed (Table 6); food staples continue to dominate land allocation (increasing in area from about 64% to 68%of total planting area, while their output value share has declined (from about 67% to 64%) (Bingswanger et al., 2008). As a consequence, the income of the majority farmers has not changed (Table 7).

Table 6 Sector share of total agricultural income (%)

Source: Bingswanger et al., 2009

Table 7 Farmer perceptions about income changes over the last five years in two villages in the Morogoro Region, Tanzania (Unit: % of farmers)

Source: field study by the first author (2010).

The changes in China’s agricultural and rural economic structure suggest that to reduce poverty in countries with a large population engaged in agriculture requires the deployment of a broadbased development strategy. A structural change within agriculture is a fundamental step in transforming the entire economy so as to overcome the ‘growth island’effect and thus promote pro-poor growth.

6. Policy determinants

It is important to try to relate the differences in agricultural development in China and Tanzania to differences in policies and economic reforms in the sector. In a sense, both countries started in similar positions, characterized by: (i) a system that had undergone collectivization of land and state marketing; (ii) a low level of productivity; and (iii) a smallholder structure of agricultural production. Both countries also adopted broadly similar reform strategies, involving: (i) decollectivization of land; (ii) an opening-up to market liberalisation; and (iii) closed international trade for staple goods. Yet there remain important differences between agricultural development in China and Tanzania, reflecting variations in: (i) investment in basic rural infrastructure; (ii) consistency and credibility of marketing reforms; and (iii) domestic capacity to elaborate and implement policies.

China’s investment in rural roads provided a strong foundation for agricultural reforms. By early 2000, rural road density in China was around 150m per sq. km. In Tanzania, meanwhile, tertiary roads had an extension of around 56,000km in 2008; around 25% of the network was not passable by motorized vehicle, implying a density of just 47m per sq. km. A further 35-50% of the network was not passable during the rainy season, while 82% was earth-surfaced, 16% was gravel and only 1.4% was sealed (URT 2008). As a consequence, transportation costs are very high in Tanzania. The World Bank (2009) estimates that transportation costs for maize in the country account for more of 80% of total marketing costs, equivalent to more than 40% of the farm gate price.

Once initiated, marketing reforms in China were staunchly sustained by the leadership, even in the face of internal pressures. As recalled by Deng Xiaoping in one of his 1992 ‘Southern Tour’ speeches:

“In the initial stage of the rural reform, there emerged in Anhui Province the issue of the‘Fool’s Sunflower Seed’. Many people felt uncomfortable with this man who had made a profit of 1 million CNY. They called for action to be taken against him. I said that no action should be taken, because that would make people think we had changed our policies, and the loss would outweigh the gain. There are many problems like this one, and if we don't handle them properly, our policies could easily be undermined and overall reform affected. The basic policies for urban and rural reform must be kept stable for a long time to come.”

In Tanzania, liberalization of agricultural market began in 1986 and came into real effect during the early 1990s. But already in the early part of this century, a set of new laws reinstated widespread power to the State Crops Boards for cash crops. This new legislation drew no distinction between the Board’s regulatory role and their right to enter the market as commercial actors; they set out with a disposition to control almost all aspects of crop development, with the criminalization of unauthorized activities as the ultimate sanction, and determined the composition of the Board so as to give a majority of voting rights to government appointees as opposed to representatives of producers or commercial interests (Cooksey, 2011). According to Cooksey, the unambiguous statist thrust in the three Bills reflected a consensus among the political class by the end of 1990s that market liberalization was no longer a viable policy option.

Finally, China developed its agricultural reform through a national system of design, piloting and scaling-up of reforms, with close central monitoring of implementation by lower tiers of government. This allowed for strong policy ownership, visible demonstration effects, policy learning and adjustments and fast and effective scaling-up. Foreign assistance was relegated to a secondary role, where both foreign policy advice and financial resources were accepted, but in a subsidiary role with respect to the primary national policy process. Policy development in Tanzania has lacked the strong institutional underpinnings found in China and remained heavily influenced by development partners’paradigms, with only partial ownership of the reforms and little adaptation to local circumstances.

7. Conclusions

Descriptive comparison of the relationship between economic, agricultural growth and poverty reduction in Tanzania and China suggests that the remarkable poverty alleviation witnessed in the latter has been facilitated by the existence of an agriculture-based economic structure with backward and forward links and a pro-poor growth pattern. In Tanzania, on the other hand, the economic structure and growth patterns prevent the poor from benefiting from growth. Experience in both countries suggests that growth should bring significant structural transformation, without which poverty will not be reduced effectively. Sectors within the economy should be connected in order to avoid isolated growth islands, otherwise growth will be substantially limited and employment will not be improved significantly. For rapidly growing sectors to have an impact on poverty, strategy should promote either those sectors that have already employed large numbers of people or those that can attract a large-scale labour force. Finally, generating a growth chain rather than a growth island is essential for linking growth and poverty reduction.

To do this, it is necessary to create links within the economic structure to fully utilize local resources and create employment opportunities.

• With a large population engaged in agriculture, a very high agricultural growth rate that produces a surplus must be promoted so that the surplus over consumption can be traded to either domestic or international markets. (China satisfies the first requirement, while Tanzania could exploit both markets given its high potential in agriculture and relatively low domestic demand.) At the same time, lower food prices for consumers will reduce the cost for

industrial- and service-sector development, as lower wages could be maintained in urban and industrial sectors.

• There should be business opportunities resulted from agricultural surplus for manufacturing or other sectors that would be able to absorb surplus labourers from agriculture.

• Countries like Tanzania (and previously China) generally have insufficient domestic capital for their economies to advance a take-off; thus, foreign investment can provide an important stimulus. Tanzania’s economy has been

growing in isolated islands, while the level of agricultural growth has been too low to produce a meaningful surplus (given the rapid population growth). Therefore, the country’s growth plan must focus on agriculture; unless this is linked with other sectors, poverty will not be significantly reduced. For agriculture to be relevant to poverty reduction, it needs to include the following components:

• The food crops grown by the majority of smallholders need to be developed rapidly in terms of both quantity and growth rate in order to provide food security and generate a surplus for income generation.

• Where smallholders are unable to create a large-scale specialized farm, crops grown on family plots should be diversified to include mixed food and cash crops, thereby increasing farmer income.

• The agricultural structure needs to be further developed, moving from cropping-oriented farming systems into more diversified ones including agroforestry, livestock and aquaculture. This should lead to an increase in farmer income, as exemplified in China, where it increased from 133 CNY in 1978 to 355 CNY in 1984 (Huang, 2008).

• A substantial increase in farmer income requires transformation of the whole economy so that it can provide

labour-intensive sectors to absorb surplus workers from agriculture. This process was clearly observed in China, where the labour force engaged in agriculture dropped from 97% in 1980 to 82% in 1985 and to 59% in 2005 (Huang, 2008).

References

Binswanger, MP & Gautam, M, 2009. Towards an internationally competitive Tanzanian agriculture. Paper

presented at Joint Government of Tanzania and World Bank Workshop on Prospects for Agricultural

Growth in a Changing World, February 24-25, Dar es Salaam.

Chen, S & Ravallion, M, 2008. China is poorer than we thought, but no less successful in the fight against

poverty. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4621.

CNBS (China National Bureau of Statistics), 2009-10. China Statistical Year Book. China Statistics Press,

Beijing.

CNBS, 2011. Summary of China Statistics. China Statistics Press, Beijing.

Cooksey, B, 2011. Marketing reform? The rise and fall of agricultural liberalisation in Tanzania.

Development Policy Review, 29 (supplement volume 1): 57-81. Overseas Development Institute.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations), 2009. FAOSTAT Database.

http://faostat.fao.org/default.aspx Accessed 5 July 2010.

FAO/WFP (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Food Programme), 2010. The

State of Food Insecurity in the World. www.worldbank.org/financialcrisis/bankinitiatives.htm

Accessed 10 July 2010.

Huang, J, 2008. Institutional Change and Sustainable Change: 30 years China’s Agricultural and Rural

Development. Shanghai Peoples Press. Shanghai.

Hoogeveen, J & Remidius, R, 2009. Poverty reduction in Tanzania since 2001: Good intensions, few

results. Technical Document of the World Bank Prepared for the Research and Analysis Working

Group. Washington DC.

Li, X, 2010a. Annotated Outline of Study on Enhancing Learning on Agricultural Efficiency and

Accelerating Poverty Reduction between Tanzania and China. The World Bank, International Poverty Reduction Centre in China. Beijing.

Li, X, 2010b. China’s Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction after the Year 2000. China Rural Economy. 2010 (4).

MAFSC (Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives), 2008. Agriculture Sector Rview and Public Expenditure Review, 2008/2009. Government Printer, Dar es Salaam.

MFEA (Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs), 2009. Poverty and Human Development Report of the United Republic of Tanzania. Government Printer, Dar es Salaam.

MPEE (Ministry of Planning, Economy and Empowerment), 2009. Poverty and Human Development Report. Research and Analysis Working Group, Mkukuta Monitoring System, Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, December.

OECD/FAO (Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development/Food and Agriculture Organization), 2010. OECD/FAO Agricultural Outlook 2008-2017. http://www.fao.org/es/esc/common/ecg/550/en/AgOut2017E.pdf Accessed 10 July 2010.

Pauw, K & Thurlow, J, 2010. Agricultural growth, poverty, and nutrition in Tanzania. IPFRI (International Policy and Food Research Institute) Discussion Paper 00947.

http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/ifpridp00947.pdf Accessed 10 July 2010.

Song, H, 2008. Rural China Reforms. China Agricultural Press.

NBS (National Bureau of Statistics of Tanzania), 2008. Tanzania Economic Survey 2008. Dar es Salaam.

URT (United Republic of Tanzania), 2008. Agricultural Sector Development Programme. Private Sector Development Mapping, Final Report for the World Bank/FAO Cooperative Programme 31 October.

URT, 2002/2003. National Sample Census of Agriculture. Small Holder Agriculture Crop Sector – National Report Vol. II.

URT 2008. Local Government Transport Program - Phase 1. Prime Minister’s Office – RALG.

World Bank, 2000. Agriculture in Tanzania Since 1986. Follower or Leader of Growth? Government of the United Republic of Tanzania, the World Bank Country Study. Washington, D.C.

World Bank, 2001. China: Overcoming Rural Poverty, World Bank, Washington DC.

World Bank, 2009. Eastern Africa: A Study of the Regional Maize Market and Marketing Costs, Report No.49831-AFR.

World Bank, 2009. Eastern Africa: A Study of the Regional Maize Market and Marketing Costs. 31 December 2009. Agriculture and Rural Development Unit (AFTAR).

扫描下载手机客户端

地址:北京朝阳区太阳宫北街1号 邮编100028 电话:+86-10-84419655 传真:+86-10-84419658(电子地图)

版权所有©中国国际扶贫中心 未经许可不得复制 京ICP备2020039194号-2