Abstract

This paper probes the role that international donors and financiers played in China’s poverty reduction efforts over the last three decades. We find that donors’ role evolved from financiers to policy advisors, to practitioners in project operations, and finally to a part with less direct involvement but significant legacies in shaping institutions, human capacities, and repertoires of concepts and ideas. We investigate three specific pathways in which donor influence has been the most evident: conceptualization of poverty, practical methodology and approaches to poverty reduction projects, and capacity building. Based on our analyses of these pathways, we find that donors are able to achieve profound institutional impact in China,largely due to the strong leadership of the Chinese state, integration of development partnerships into China’s existing governance system, and a graduated approach in introducing changes that allows for sufficient experimentation and local adaptation. In conclusion, we recapitulate donors’ role in catalyzing institutional changes. The way these changes have occurred and been sustained provides us with food for thought as China forges its own partnerships for poverty reduction with the rest of the developing world.

1. Introduction

In the past three decades, China has accomplished the unlikely feat of lifting nearly a quarter billion people out of poverty. Apart from judicious policies and a stunning growth record,international donors are often a neglected actor in

China’s development discourse. In this paper, we seek to answer the question: What role did international cooperation play in China’s successful poverty reduction efforts?

Given China’s current economic prowess and strategic importance, it is easy to forget that China once was and still is a major recipient of development assistance. From 1979 to 2006,China received a total of 6.3 billion USD in multilateral and bilateral grants.1 The World Bank (WB) was once the largest foreign investor in China in the 1980s, providing concessional andcommercial loans for infrastructure, industrial, and social development as well as technological transfers.2

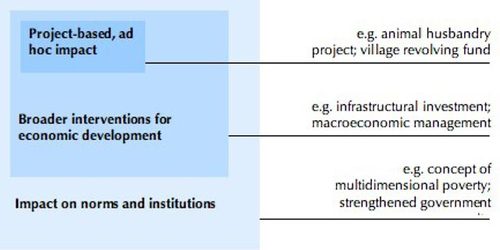

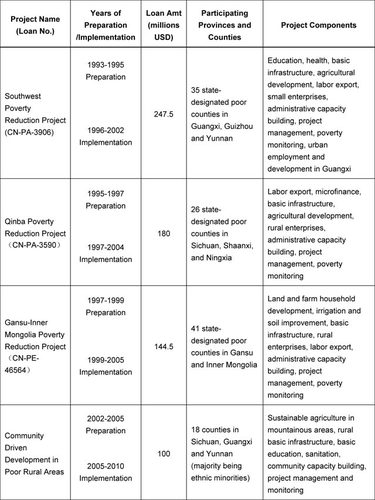

Donors influence poverty through a variety of channels (Figure 1): First, donors exert impact through narrowly defined poverty reduction projects at the micro level. For example, targeted animal husbandry projects can tangibly raise household income. We call this type of intervention ad hoc, project-based impact. Second, poverty may decrease as an indirect result of donor's macroeconomic intervention. A substantial portion of World Bank support did not target reducing poverty per se, but facilitated the overall development of a market economy and spurred growth, which in turn provided an enabling environment for alleviating poverty (akin to the socalled “trickle down” supply-side economics). Infrastructural investments and specific policy recommendations for market reform andmacroeconomic management would fall in this category. Third, donors influence the norms and institutions in China’s poverty reduction efforts. Although this influence is the most fluid and difficult to qualify, it is arguably the most profound; donors played an important role in influencingChinese policymakers' conceptualization of poverty, modified approaches to how poverty reduction projects are conducted and managed, and developed human capacity which is the ultimate change agent in any developmental process.

As China’s economy grows, the first two influences have become relatively unimportant. Development assistance financially accounts for a tiny proportion of China’s sizable economy. Foreign direct investments by far overwhelm aid

flow. Financing channels for enterprising activities have proliferated. Even in providing public goods, rapidly rising intergovernmental transfers for poor counties after the 1990s have further diminished the relevance of donor funds. Donors’ role as a financier either at the micro or macroeconomic level has declined. Instead, it is the influence on

norms, institutions, and policy discourse that persists.

Thus, this paper focuses on the third sphere of donor influence: norms and institutions. More specifically, we examine how international donors have impacted China’s conceptualization of poverty, implementation of poverty reduction projects, and efforts at capacity-building. We trace the ever-evolving role of international cooperation in China's fight against poverty, focusing on China’s largest donor, the World Bank, in order to demonstrate specific cases and approaches. We also identify some of the challenges foreign donors face in China.

There are several implications of our study. First,most donor evaluations assess the socioeconomic benefits of individual projects. Less has been written on the systematic impact of international donors on China’s overall approach to poverty reduction. Our study makes an attempt at filling this gap. Note that, though related, our paper is not a discussion on the merits and limitations of the “Chinese model” for development per se. Our study concerns a relatively narrow and focused range of issues: the evolution of China’s poverty reduction policies and practices and the role foreign donors play in this process. Second, China is rapidly ascending on the world stage as an economic engine, investor, and provider of development assistance. Understanding international donors' experience in China may serve as a useful reference as China forges its own poverty reduction strategies overseas.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 gives a chronological overview of international donors’ engagement in China. Section 3 describes the institutional framework of China’s poverty reduction system and its interface with international donors. Section 4 investigates in depth three aspects of donor influence: the conceptualization of poverty, practical methods in conducting poverty reduction projects, andcapacity building. Based on the cases and experiences provided, Section 5 then analyzes the mechanism and process through which international donors achieved institutionalized impact. Section 6 concludes and applies the insight from this paper to China’s current engagement in development partnerships overseas.

2. Poverty Reduction and International Donors: An Overview

This section provides a brief overview of the course of poverty reduction in China and international partners’ involvement therein.

2.1 Indirect Support

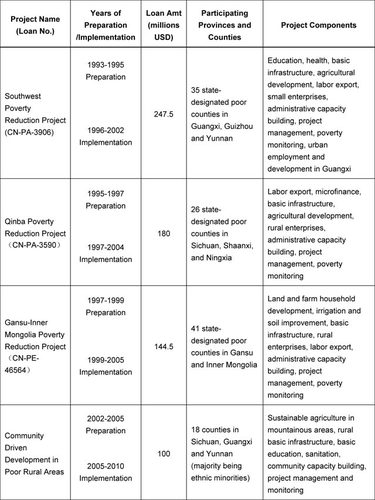

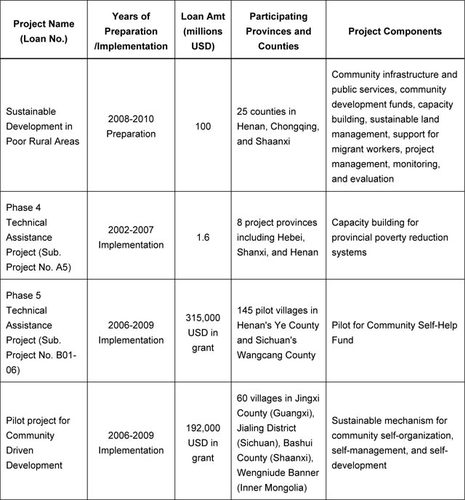

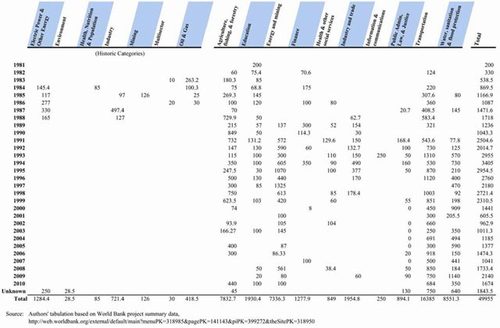

International donors’ engagement in China’s poverty reduction efforts has been relatively short. Although China has long been a recipient of development assistance, earlier loans and grants tended to focus on infrastructural investments, stimulating economic growth, or providing technical assistance in a particular sector without targeting poverty per se. As Table 1 shows, from 1981 to 1990, the World Bank approved of over 12 billion USD in loans to China. More than 2.4 billion was directed toward transportation, 1.7 billion to energy and mining, and nearly one billion toward industry and trade, compared to 850 million spent on education and 130 million on health. This confirms Xu’s observation that in the 1980s the majority of World Bank loans to China financed infrastructure and industrial development and that funds on directly alleviating poverty came secondary. 3 This trend was not limited to cooperation with the World Bank. Sichuan Province has received multilateral and bilateral loans since 1985 from the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and a host of donor governments. Until 1991, Sichuan secured a total of 341million USD in loans for industrial development, compared to 10 million in health, 12 million in education, and none in environmental protection.4

Donors’ focus at the time reflected China’s developmental course and was in many ways consistent with the country’s own priorities in poverty reduction. During the 1980s, when China was just awakening from decades of political turmoil and rigid economic planning, the national priority was to re-establish the basic economic infrastructure and market incentives. Consistent with this historical trend, China’s initial accomplishments in reducing poverty may be deemed as byproducts of broader policy reforms. The implementation of the Household Responsibility Systems in 1982 provided farmers with market incentives and stimulated production, thereby raising incomes. This policy ensured a majority of farmers - who now had equal access to land on a per capita basis - a minimal, subsistence standard of living.

It was not until the mid-1980s that the central government formally established programmatic efforts in reducing poverty. These efforts were again centered on stimulating economic activities, reflecting China’s trademark approach of “development-oriented poverty reduction” (开发式扶贫). National, large-scale programs included “Food for Work” (以工代赈), rural infrastructure building, and subsidized loans administered through China’s Agricultural Bank to farm

households and township and village enterprises (TVEs). In 1986, a specialized, multi-leveled institutional structure for poverty reduction, spearheaded by the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development,

was established. The government for the first time established official poverty lines and identified a total of 331 poor counties. During this period, poverty reduction was primarily a state effort and the participation of international actors remained limited. The involvement of the WB and other donors in this period remained focused on economic policy recommendations and infrastructure and industrial financing.

Table 1 World Bank Loan (Approval) to China by Sector 1981-2010 (mil USD)

2.2 Direct Participation

A new phase began with the implementation of the National Seven-Year Priority Poverty Reduction Plan (1994-2000, 八七扶贫攻坚计划). After over a decade of high growth, while China’s poor declined in numbers, they became increasingly bound to specific locations. Poverty persisted in the mountainous areas of the southwest, watershy

regions of the northwest, Qinling and Ba mountain area (Qinba), and the Tibetan plateau. This pattern called for targeted and nuanced strategies different from the blanket approach of the previous decade. In 1996, the National

Poverty Reduction Conference established a “poverty reduction responsibility system” where provincial and county leaders are held directly responsible for the effectiveness of poverty reduction efforts. If the prior decade was marked

by the predominant role of state efforts, this period saw a more decentralized approach and rapid proliferation of actors with the growing participation of international organizations, ministerial and sectorial actors, and civil society

groups.

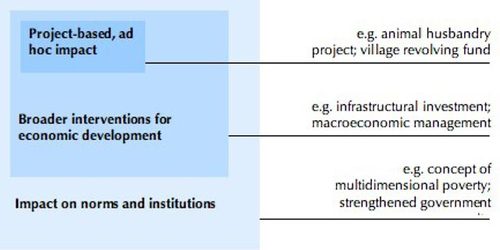

Concurrently, the Work Bank gradually shifted its focus to include poverty reduction, agricultural development, and environmental protection as primary working areas.5 In 1993, the WB initiated its first integrated rural poverty reduction project, the Southwest Poverty Reduction Project (SWPRP), in Guangxi, Yunnan, and Guizhou provinces. The SWPRP was an ambitious, decade-long commitment with a total investment of 486 million USD.6 From Table 1, we see that in the 1990s the WB, in addition to supporting the energy and infrastructure sectors, maintained a consistent emphasis on agriculture and education and significantly expanded its involvement in water and sanitation. After the SWPRP, the WB also introduced poverty reduction projects in Qinba, Gansu, and Inner Mongolia.7

At the time China’s fiscal system was under significant strain, with jarring regional disparity and a weak central coffer incapable of providing effective equalizing transfers. Donor funds potentially could fill this void by helping poor

counties provide public goods (however, the actual fiscal impact might have been ambiguous.We briefly consider this possibility in Section 3). As we shall elaborate further, in this period donors played an active role in shaping the content and delivery of poverty reduction programs. These influences may well have contributed to China’s diversified approach to alleviating poverty in subsequent years.

China’s poverty reduction in the last decade has been guided by the Development-Oriented Poverty Reduction Program for Rural China (中国农村扶贫开发纲要2001-2010). The Program marks a new chapter of development-oriented poverty reduction in that basic food and shelter are no longer a primary concern for the majority of rural poor. The main issue now has become bridging the rural-urban divide, reducing regional disparity, and propelling the poor toward the xiaokang standard of living. In addition, marking the poor along county boundaries is no longer appropriate as they are now increasingly dispersed in pockets of poor villages. In response to this trend, the government designated a total of 148,000 poor villages nationwide in addition to poor counties, narrowing focus further toward the

local levels ( 整村推进). Arguably under the influence of international organizations, China’s conceptualization of poverty has now moved closer to prevailing international norms: while early poverty reduction strategies were focused on income poverty, they now take a more integrated approach and place greater emphasis on multiple dimensions of poverty including education, public health, and the environment in addition to raising financial incomes. Channels of fund flows and participation continued to expand with the involvement of international actors and innovative partnerships between the government and nongovernmental actors. The World Bank introduced two new projects in this period including the Community Driven Development (CDD) project and the most recent Sustainable Development Project (see Appendix A for further details).

2.3 Declining Influence?

Although most multilateral and bilateral donors still maintain their operations in China, their funding and areas of operation have contracted substantially in recent years. Several prominent bilateral donors, including DFID and GTZ, are soon to withdraw from China or downsize dramatically. DFID China is in its last year as a separate bilateral aid program, after which its operation will be absorbed into ambassadorial affairs. GTZ also plans to significantly curtail their programming after the current funding phase. According to Table 1, the World Bank’s loans to China have also seen decline in the previous decade relative to the peak in the 1990s.

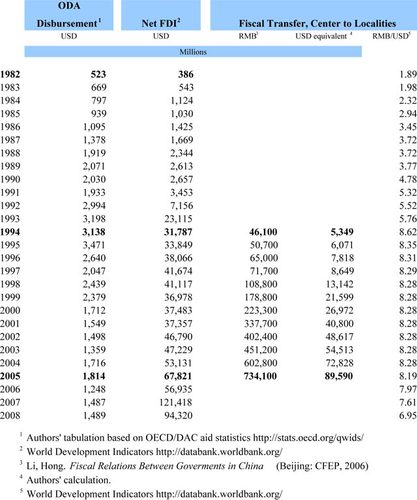

What causes donors to withdraw? First, as was mentioned before, as China's economy grows and the fiscal transfer system strengthens, donors' leverage has declined. Table 2 shows donors funds (in both grants and loans) relative to FDI and fiscal transfers to poor counties. In 1982, development assistance flow exceeded total FDI. In 2005, however, it measured at less than 3 percent of FDI inflow. Equally stunning is the exponential growth of fiscal transfers from the center to localities since 1994. In 1994, the amount of transfer was only modestly greater than ODA disbursement; in 2005, fiscal transfers even exceeded FDI by a substantial margin. Second, OECD donors are under increasing pressure from their domestic constituencies. Voters have come to perceive China as a global power that does not need development assistance. 8 Remaining poverty in China is increasingly seen as a domestic affair that ought not to burden international resources. Third, the recent global financial distress has shifted spending priorities

among many OECD governments.

To the extent that donors are still involved in China's development, their role gradually evolved from a provider of funds to that of safeguard for the country’s formidable economic engine. Donor projects are increasingly geared toward environmental preservation and sustainable development. The WB’s latest undertaking is the “Sustainable Development in Poor Rural Areas” program implemented in Chongqing, Henan, and Shaanxi. Another growing area of engagement is trilateral cooperation. As China conducts more poverty reduction projects in other developing countries, OECD donors are seeking dialogue and coordination with the Chinese government as well as with private actors in these endeavors. The 2003 Country Assistance Strategy (CAS) already reflects the changing nature of the China-World Bank Group relationship: “China [is] positioned not only to receive Bank assistance, but also to share

lessons of its development experiences more broadly and contribute to thinking on global development issues of common concern.”

A related trend is the shifting balance of power between China and foreign donors in negotiating loans and grants. As China's fiscal position strengthens and financing channels proliferate, donors' bargaining positions have deteriorated. Meanwhile, with the legitimacy and impact of international development assistance coming under greater scrutiny, donors are under growing pressure to demonstrate the effectiveness and sustainability of their poverty reduction projects.

Table 2. ODA Disbursements, Net FDI, and Fiscal Transfers in China

2.4 Donors’ Changing Role

This section has provided an overview of donor engagement in the context of China’s poverty reduction endeavors. From the discussion above we can see that donors assumed changing roles over the country’s course of development. From a provider of infrastructural support to direct project engagements to a partner in the global fight

against poverty, donors’ position as a funder and financier has declined while their institutional and ideational legacies continue to evolve. But what exactly are these legacies and how did they leave such profound impact on China’s approach to poverty? We address several aspects of donor influence in Section 4.

3. International Cooperation: The Institutional Setup

Before analyzing pathways of donor influence, it is necessary to describe the institutional framework governing China’s poverty reduction efforts and its interface with international donors.

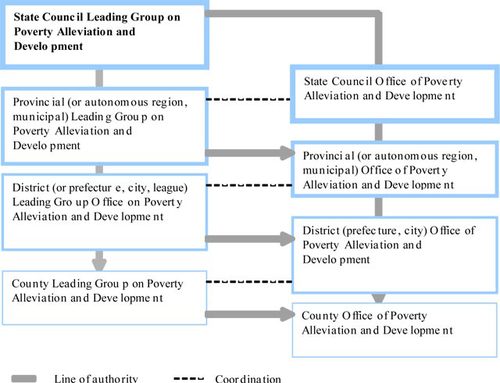

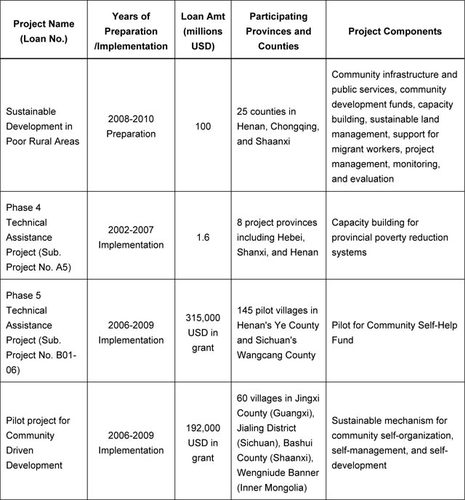

China’s poverty reduction system features a

Figure 2. China ’s Poverty R eduction System: Administrative Structure

government-led, top-down administrative structure. It is an integral part of the overall governance apparatus in the Chinese state.9 Figure 2 depicts the lines of vertical authority and lateral coordination among comprising entities. The State Council Leading Group, established in 1986 and consisting of members from various central ministries and commissions including the National Reform and Development Commission, Ministries of Commerce, Agriculture, Transportation, Finance, Education, Health, and policy banks, is responsible for devising the overarching strategies

and long-term, systemic plans. Its lateral corresponding entity, the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development (LGOP), produces policy recommendations and manages daily operations, including determining the criteria for classifying poverty, coordinating among various agencies involved in poverty alleviation, directing and monitoring fund flows, and engaging in international cooperation. The lateral structure at the center then propagates through the lower levels of the government, whereby localities are responsible for making detailed plans and policy implementation.

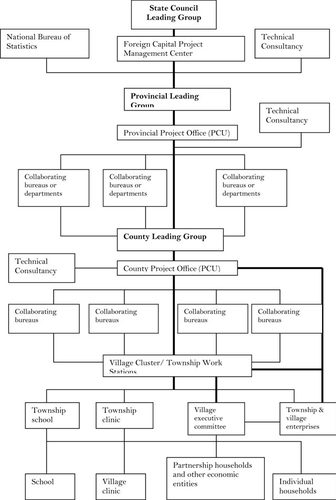

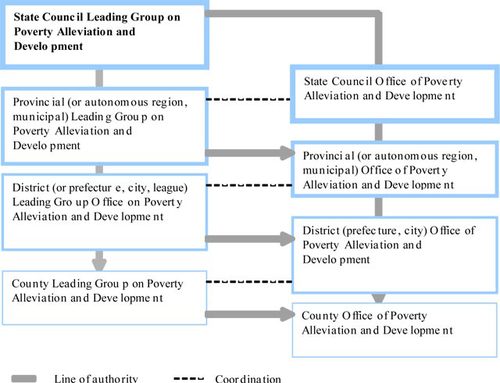

Figure 3 Administrative Apparatus of a Typical World Bank Project

International donors and financiers work closely with the Chinese state. At the central as well as provincial levels, LGOP has a distinctive arm for managing international cooperation, the Foreign Capital Project Management Center (FCPMC). These centers serve as the interface, or “window agencies,” between the Chinese governmental apparatus and international donors and are typically staffed with personnel from LGOP or relevant sectorial ministries. LGOP and its comprising FCPMCs are permanent, institutionalized fixtures. In addition, there are project- or donor-based administrative units operating at the provincial, county, township, and village cluster (xiang) levels. These project offices (xiang mu ban) are functionally equivalent to Project Implementation Units (PCUs) and typically an administrative component of the local Poverty Alleviation Offices. The project staff are financed through governmental budgets and independent of project loans or grants. Taking a more microscopic view than Figure 2, Figure 3 illustrates the institutional hierarchy of a typical World Bank poverty reduction project:10

Figure 3 shows by example that international donors are an integral part of China’s poverty reduction system and the rest of the governmental apparatus. Donor projects operate in a similar administrative structure with a top-down chain of command and responsibilities. With few exceptions in the later stages of cooperation, all negotiations involving international partners must be conducted at the central level, complemented by consultations with the localities. As we shall elaborate in the latter half of the paper, this centralized and yet consultative process helps to

harmonize various development actors under coherent, long-term planning.

The integration of international donors with China’s existing institutions is not only reflected in the administrative mechanics, but in financial responsibilities as well. From the beginning of the reform era as China first opened its doors toward international donors, the country established a system for managing development finance, led by the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), MOFCOM initiates discussions with bilateral and multilateral donors primarily on grant projects while the Ministry of Finance serves as a window agency for international financing institutions including the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. This general partition of responsibilities continues today, where loan funds in particular are intricately married to China’s complex fiscal systems.

International funds in the early reform era, as we noted earlier, did not support poverty reduction programs per se. After the establishment of LGOP and international partners’ engagements became more direct, more funds have been directed toward devising and implementing projects. These funds are subject to the same designation of

responsibilities as outlined in the previous paragraph. LGOP as a policymaking and operational entity does not actually administer donor funds (even though it may make certain allocative decisions). Financial responsibility for

international loans continues to flow through the existing fiscal channels from the Ministry of Finance to local governments.

At the sub-national level, China is rather unique in transferring donor funds as loans instead of grants to the lower levels of the government. This transfer often incurs additional interest charges to compensate for the administrative costs or to maintain comparability with domestic lending markets. A 2% low interest loan provided by the World Bank, for example, may be loaned at 5% annual interest to farm households.11 Even though only the central government has the authority to conclude loan contracts with international donors, the ultimate liability to repay resides with the local counties as the end users. When counties fail to make these payments, provincial authorities automatically deduct corresponding amounts from fiscal transfers to the counties in subsequent years. This penalty mechanism goes further to demonstrate how much donor fund flows have fused with China’s existing fiscal system.

4. Donor Impact: Conceptualization, Approach, and Capacity

In this section we return our attention to donors’ institutionalized legacies in China’s approach to poverty alleviation. We investigate three main aspects of donor influence: conception of poverty, practical approach to poverty alleviation projects, and capacity building. By analyzing substantive experiences and cases in these areas, we then draw some conclusions on how donors actualize institutional legacies in Section 5.

4.1 Conceptualization of Poverty

4.1.1 Income and growth based conception of poverty

As was mentioned in Section 2, China’s broadbased poverty reduction approach of the 1980s had several characteristics. First, it was focused on economic development. As Wu noted, this strategy had two linkages: one, poor areas could promote economic growth through the development of natural resources; and two, economic growth in turn could reduce poverty.12

Second, income was the dominating benchmark for measuring poverty. Poverty was defined in totality by official poverty lines and the benchmark of success was simply how many households were lifted above these lines. In 1984, the central government calculated poverty lines based on the minimum expenditure on a weighted basket of

goods and services. The measure was then updated yearly to reflect changing prices. A singular income measure separated the poor from the non-poor.

Third, poverty was calibrated in terms of geographically contiguous areas (pian qu, 片区). In the 1980s, China had 331 poor counties in 18 cross-provincial poor areas. Policy prescriptions were broad-stroked and did not reflect a great deal of local variations. Fourth, there lacked integrated and coordinated consideration on different aspects of poverty. Since poverty was predominantly defined by income, governmental departments in health, education, and other public services were not traditionally seen as part of the poverty reduction system. The integrated, cross-sectorial approach we take for granted now was missing.

The policy conceptualization of the 1980s had its drawbacks. As Wang et. al. note, poverty reduction of that period suffered from “low efficiency. 13 Large geographic definitions of poverty to some extent reduced costs in screening

and administration, but the method also spread limited resources too thin.14 Broad-stroked policies might have made sense when poverty was pervasive, but as local economies developed, different groups and localities benefited

disproportionately from the economic gain. Widespread poverty gradually became replaced by more concentrated and chronic poverty, which required more specific, localized strategies as opposed to broad policy prescriptions. While

economic development is undisputedly important, not all poor areas are equally endowed in resources and accessibility and conducive to economic take-off.

Defining poverty based on a simple income cut-off also was problematic: 1) It does not take into account the multiple dimensions of poverty and deprivation. The single-minded pursuit of income neglects the poor’s access to healthcare, education, and other vital components of human wellbeing. 2) The local government’s need to raise

household income quickly, often through resource or agricultural developments, could potentially compromise the goals of sustainable development if not presented with necessary safeguards. 3) Defining poverty with a cut-off point neglects the issue of vulnerability. Once income has risen above the poverty line, counties and villages are no longer eligible for favorable pro-poor policies while, in fact, the poor remain struggling around that artificial line. In fact, the definition of the poverty line itself could be susceptible to subjectivity.15

4.1.2 Changes in Conceptualization

It was within the context described above that the World Bank initiated its first poverty reduction program (SWPRP) in 1993. At the time, a number of program components brought innovations to the prevailing mentality in China’s poverty reduction strategies.

First, identify villages as the focal unit of poverty alleviation. In a 1992 research report, China: Strategies for Reducing Poverty in the 1990s, the World Bank already pointed out that resources should be directed to the poorest villages instead of being dispersed over larger geographical areas. This idea was in contrast to the predominant

large-scale, blanket approach to poverty alleviation characteristic of governmental policies at the time. The 2002 report, China: Overcoming Rural Poverty, again called for better targeting and a greater emphasis on the indigently poor in mountainous areas and among ethnic minorities. Concurrently in 2001, China launched a set of village-based strategies, Zheng Cun Tui Jin, to be implemented in 148,000 state-designated poor villages throughout the country (recall Section 2).

The World Bank likely played a role in this change in policy discourse. As interviewed officials at the FCPMC noted, better targeting was a legacy of World Bank projects. Prior to the WB’s engagements, the finest level of project planning would be at the county and the focus remained on building roads and enterprises. The WB programs,

however, propelled closer focus on poor villages and households and their particular needs and challenges. “Whatever problems a village has, we work on those problems.” 16 In 2005, 49.1% of villages under the poverty surveillance of the National Statistics Bureau participated in various types of village or household-based project activities, up 10% from just three years before.

Second, focus on the poorest of the poor. China’s early poverty reduction strategies were guided first and foremost by economic development. That, combined with a localized repayment responsibility system for project loans, meant that efforts tended to shy away from projects that did not bring immediate economic returns. A project

officer at the Shaanxi Qinba Project Office recalled that, when the Bank and Chinese government were negotiating the choice of project sites, the Chinese side proposed to select areas that were moderately poor and had good potential for economic development. The WB, however, insisted on locating in the poorest, southern area because this was the population that needed assistance the most.17 The difference in mentality was evident: China’s poverty reduction was to a certain extent oriented by economic returns, while WB’s strategy was guided principally by fulfilling basic needs of individuals and communities. Even if a project implied negative financial returns in the short term (much of the public service provision would belong in this category), the WB still considered it a worthy investment for its social benefits. The two approaches are complementary; without economic viability, no poverty reduction programs can be sustained forever, but only considering short-term economic return would preclude the truly indigent. The involvement of WB

helped push China’s poverty reduction policies to serve the very bottom of the poor and incorporate a more humanistic dimension.

Third, considering multiple dimensions of poverty and vulnerability. As was discussed above, China’s early poverty reduction was focused on raising incomes. Alan Piazza, a longtime “China hand” in WB poverty programs, incisively pointed out that poverty alleviation without health and education components could not constitute true

reduction in poverty.18 The WB possesses a set of sophisticated poverty assessment tools that not only measure income poverty, but also vulnerability, relative poverty, and degrees of deprivation in resources and services. It thus

constructs a holistic conceptualization of poverty and provides an integrated approach to reducing it.

Today, governments and international organizations agree on the necessity of combating poverty’s multiple dimensions. However, what we take for granted now was once a point of intense contention between some government officials and WB project personnel. In establishing the Qinba project, the former was reluctant to fund

health and education components, citing that these projects do not result in economic returns.19 The officials’ position was understandable in that 1) the mentality of the time did not consider public services a crucial part of poverty reduction and 2) the tangible pressure of having to repay WB loans in the future discourages them from making unprofitable investments. At the WB’s insistence, however, the Qinba project proceeded as an integrated rural development and poverty reduction program with sizable investments in rural public services. Donor projects typically require matching funds. In China, these matching funds come from both provincial and county contributions (in some agricultural projects, some funds come from farmers). Through such requirements, a secondary effect of the project may have been to reshape public spending priorities and direct more resources to providing public goods. For example, the SWPRP project emerged at a time when poor county governments were in desperate need of funds while the central government was in an equally compromised fiscal position after years of tax crunch. The matching

funds requirements were able to force more fiscal transfers from the province to poor counties and facilitate greater public investments.20

Fourth, fostering sustainable development. Sustainable development is one of the core concepts in WB’s poverty reduction programs. A World Bank project undergoes rigorous socioeconomic and environmental impact assessments. Potential impacts are taken into consideration in project design and weighed against economic benefits. This practice again brought innovation to China’s existing poverty reduction strategy. In the National Seven-Year Priority Poverty Reduction Plan, there was no reference to environmental protection or sustainability, whereas these concepts are now the mainstay of the 2001-2010 Development- Oriented Poverty Reduction Program for Rural

China. The guideline lists sustainable development as one of the five fundamental strategies in poverty reduction.

To summarize, international donors played a facilitating role in shifting and enriching China’s conceptualization of poverty and its multifaceted manifestations. This change in mentality did not occur overnight and the convergence in

mentalities was mediated through graduated compromises, revisions, and progress between the donors and recipient. The mechanisms that drove this process will be the focus of our discussion in Section 5.

4.2 Practical Approaches in Poverty Reduction Projects

Donors not only played an important role in shaping policymakers’ ideation of poverty reduction, but also contributed to the way China conducts and manages its poverty reduction efforts. There are two main aspects of influence: one is the introduction of participatory approaches; the other is a rigorous project management process with effective monitoring and evaluation practices.

4.2.1 The Participatory Approach

According to the World Bank, participation is “the process through which stakeholders influence and share control over priority setting, policy-making, resource allocations and access to public goods and services.” 21 In Section 3, we already described the highly hierarchical administrative structure that governs China’s poverty reduction efforts. So how does a participatory approach function with the top-down, government-led poverty reduction system in China? Indeed, inclusive participation in program planning and formulation was all but a foreign concept to Chinese officials at the time. As an interviewee at a government office bluntly shared, “Bottom-up planning was simply unheard of. We had always operated in a world where the top makes policies and the lower levels execute.”22

Not only was the idea of participation new, but its application also faced practical difficulties. The World Bank Participation Sourcebook (1996), for example, was a 259-page manual with dauntingly complex protocols and at jarring odds with China’s policy process at the time, where mandates traveled through tiers of the government in the

forms of terse decrees and announcements. In addition, the rugged natural environment added to implementation difficulties. The poor tended to locate in mountainous areas where villages were far apart from one another. It was both difficult and costly to gather villagers for planning meetings.

Despite these challenges, the participatory approach slowly took hold in China thanks in large part to innovative local adaptations. This long process again began with the WB’s SWPRP project, which pioneered the now famous “Three Charts and One Picture” method for village-level planning in China. The three charts refer to 1) village vital statistics, 2) tabulation of project investments, and 3) annual investment plan. The one picture maps out project activities in the village. The charts and picture are based on participatory planning meetings and publically displayed on the walls of village committees. The public display serves several purposes: 1) it continues to disseminate project information among villagers beyond costly, infrequent meetings; 2) the public materials make it easier for villagers to measure and monitor the progress of project activities against the collective goals of the community; 3) the displays also serve as a source of information for the higher authorities during local inspection. County plans are then based on the synthesis and consolidation of village level plans. During the SWPRP project, as poor counties desperately lacked resources, participation was piloted only on a limited scale at three project villages per county. Despite the

limitation in scale, participation featuring “Three Charts and One Picture” provided a cost-effective, gentle introduction to participatory local planning in China’s traditionally top-down poverty reduction system. Achieving lasting impact, the approach was broadened to additional villages, and continues to be used in China’s poverty reduction work today.

Participation has been broadened and deepened substantially since the initial SWPRP project. By the fourth phase of the WB’s poverty reduction program, three participating provinces, Guangxi, Yunnan, and Sichuan had already been properly initiated in the participatory approach through their engagements with the SWPRP and Qinba projects. In addition, China was now equipped with a sizable team of project professionals well versed in the philosophy of grassroots participation. Participation thus became a much more inherent and far-reaching element in the fourth project phase. In Sichuan the project invested more than 400 million Yuan covering more than 500 villages.

Project staff were able to apply a participatory method throughout all phases of the project despite its large scale. The project produced and distributed a participatory work manual, applied the methods not only to needs assessment and

project planning, but also to implementation, management and maintenance. In Mei Gu, for example, villagers were able to devise, completely out of voluntary organization, a set of management rules for the local drinking water source that was both sustainable and creative (Box 1).23

Case 1 Participation in Mei Gu24

Mei Gu is a fourth-phase project county in western Sichuan where a vast majority of the population is of Yi ethnicity. In Qianha village, the project began with a household survey in 2006 to identify needs and difficulties facing the community. An allvillage meeting was then held to prioritize demands (out of 385 total populations 170 attended), where the community decided on planting fruit trees as a source of cash income. After the seedlings arrived, the community convened another meeting and elected 20 technically competent households to serve on the maintenance team for the orchard and provide extension to villagers. The community formed a financial management system with stipulated reporting and audit schedules. A share of orchard profits goes to a collective village fund that contributes to maintaining basic infrastructure in the village. These project activities are not particularly new; what makes it special in the Chinese context, however, is the thorough adoption of a participatory approach throughout the planning and management process.

A second telling example also pertains to Mei Gu: with the facilitation of the WB project staff, beneficiaries of a local drinking water facility decided on and implemented a sophisticated metering and billing system. Even when the local government tapped the supply, it was held accountable by the communities and was required to pay for its consumption. Pooling payments from beneficiaries, the collective fund not only pays for the maintenance of the facility itself, but also uses the surplus to provide additional assistance to the most needy households in the village. All these

measures resulted from villagers’ own initiative and organization and were not in the original project formulation. The participatory approach took maximum advantage of villagers’ creativity in system design.

From a heavily hierarchical system to one that

seamlessly integrates local participation, China’s engagement with the participatory approach was a gradual process. The approach was ultimately able to stick not just because of graduated introduction and appropriate local adaptation, as outline above. It has also served a positive function in the existing institutional setup, potentially improving project outcomes. While government preeminence and grassroots participation appear to be complete opposites, they do not contradict one another in practice. In fact, in the context of a highly hierarchical policy process, policymakers, local practitioners, and village communities can all benefit from stakeholders’ inclusive participation. The process facilitates better information flow across different levels of the hierarchy and guides program design

and execution to suit the needs of the target population. Appropriate program design then paves way for smoother implementation. From the perspective of the local government, when upper-level policies mismatch local needs, county officials end up bearing the burden of maintaining a difficult balance between the demands from authorities and from local communities. So there exist incentives for the local government tosupport greater participation. From the perspective of the central or provincial governments, better participation from the public not only channels more information upward, but also mobilizes the communities to serve as monitoring agents for local implementation of upper-level policy prescriptions. Finally from the perspective of villagers, participation provides mechanisms for

coordinating differing preferences and opinions among individuals and groups and for reaching consensus. Practices that are derived from group consensus are more likely to last as 1) the participatory process legitimizes group decisions; 2) the community obtains a sense of ownership from the exercise; and 3) the resulting program

formulation is objectively better suited for local circumstances.

In short, international poverty reduction projects make an important contribution to China’s poverty reduction work by introducing the participatory method in project design, planning, and implementation. The success of participation in China derives from two aspects: 1) the approach was introduced in a controlled, gradual manner and adapted to local circumstances when necessary and 2) the method does not change fundamentally China’s policy process but serves as a constructive addition that improves the functionality of existing institutional arrangements.

Case 2 Community Driven Development (CDD)

Consistent with a participatory approach, international donors introduced CDD as an important form of project organization. Financially, community directorship was reflected in allocating funds directly to grassroots communities. This move was a major breakthrough in China’s traditional tiered fiscal system and required substantial coordination between China’s Ministry of Finance and project offices. In order to ensure effective and efficient use of the funds, a

byproduct of CDD was to facilitate the transparency of fund use at the village level: the project established mechanisms for public disclosure and soliciting and addressing public complaints. Fund use was itemized and shown in detail to villagers with hotline numbers to report any misconduct.

Prominent examples of CDD include “Community Development Funds.” Although international experience is widely available in setting up Village Revolving Funds or other forms of communitybased collective finance, experiences had been rare in establishing a government-led community fund. Here, the inception of CDD in China took a similar course to that of participation: it began with small-scale experiments in 20 villages and, based on the pilot experience, the project developed guidelines for further expansion that were not only applicable to the rest of the project areas, but also laid foundations for the government’s broader policy development. The pilot results from the

WB’s TCC5 project, for example, contributed substantially to the Handbook for Community Development Funds in Poor Villages, a guidebook prepared jointly by the State Council Leading Group Office for Poverty Reduction and Ministry of Finance. In September 2009, the ministries released further announcements that elevated the guidelines to the level of importance of national policies

The adoption of CDD in China in many ways confirms the general lessons in modal change: 1) the process was gradual and began with experiments; 2) it operated in and improved upon China’s unique political and administrative

systems.

4.2.2. Modernization of Project Management

In addition to a participatory approach, international donors’ other contribution includes facilitating the modernization of project management. In the 1980s, China’s approach to project management demonstrated several

limitations. First, project design was subject to central planning and decisions were made according to administrative hierarchy. International donors, in contrast, tended to base decisions on cost-benefit analyses. Second, there lacked specific standards and protocols in project design and implementation. This tendency in part reflects China’s general inclination in policy dissemination: the higher levels set broad policy directions, leaving the localities substantial

discretion in interpreting and calibrating these broad mandates. This flexibility is a double-edged sword. While it allows for appropriate local adjustments and adaptations, it also reduces the extent to which various actors can be held accountable for their conducts; when things just sort of “work out,” or don’t, it is difficult to track exactly what went right or wrong, who was responsible for what, and just exactly what outcomes were expected and if they indeed were

accomplished. In addition, without standardized processes, it was difficult to maintain continuity of the work processes through personnel changes and fluid project demands. Third, regular monitoring and evaluation (M&E) were missing. The limited extent to which evaluation occurs concentrated on simplistic, measurable hard

indicators, i.e., how many kilometers of roads were built or how many households edged above the poverty line. More attention was paid to reaching nominal targets and getting things done rather than how they were done and what impacts they achieved. These limitations dictated that China’s poverty reduction work unfolded in a somewhat haphazard, discretionary fashion. Poverty reduction policies and programs were not always efficient in achieving their intende outcomes. The so-called “policy implementation gap,” widely known among scholars, also applies to project execution. It precisely refers to the phenomenon where local policy actualization may deviate from the intent of higher-level policymakers due to either misaligned incentives or inefficiencies in execution.

International actors brought substantial changes to China’s approach to project management. In the early 1980s, when the World Bank assessed China’s capacity for managing projects (though not poverty reduction projects per se), it found that the country was competent in accomplishing the essential elements in project design and

implementation but lacked specific management skills such as cost-benefit analysis and accounting standards. The Bank’s some 280 investment projects that followed employed a standardized, uniform set of protocols and management framework for project design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation. This framework consistently exposed Chinese practitioners to models of modern project management. Apart from exposure and learning on the job, international donors conducted formal training for Chinese staff. Between 1982 and 1987, the World Bank Institute, cooperating with Chinese universities, trained hundreds of officials and professionals in project management skills. 25

Considering poverty reduction projects more specifically, we observe that pioneers such as the SWPRP project played a similar facilitating role to their counterparts in investment and commercial projects. The SWPRP project introduced Chinese practitioners to several basic tools in modern project management:

1) One is evidence-based decision making. Even though poverty reduction projects cannot be judged simply by cost-benefit ratios, the basic principle still stands where projects seek to maximize intended outcomes (be it economic return or social development) with the least input.

2) Another innovation is procedurization and standardization, which involves conscious definition and sequencing of detailed project components. A World Bank project is complete with scoping and feasibility studies, project design,

formulation of detailed activities, identifying needs for technical assistance, public hearings and stakeholder consultations, budgeting, procurement, assembling staff and experts, establishing regular monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, mid-term adjustments, and final completion. And for each of these components in the project life cycle, there are ready protocols to follow. These protocols are carefully formulated to correctly shape relevant actors’ incentives and discipline their actions. For example, the international bidding protocol inprocurement encourages fair competition amongsuppliers, increases transparency and reduces favoritism, and enhances the overall quality of

acquired project materials. The reimbursement protocol helps to reduce waste and ensures project funds are spent appropriately. When projects are supported by effective protocols, they rely less on the virtue of managers and staff to succeed. Projects become governed more by objective standards and procedures and less by individuals. Standardization provides for measurability and transferability and reduces uncertainty in project management. Relevant actors know what to expect. Standardized processes are also easy to replicate and scale up.

3) Installation of regular, field-based internal monitoring and evaluation. In all World Bank projects, M&E have been thoroughly integrated as an inherent part of project operation. In addition to the inspection team deployed by the bank twice a year, the national and provincial project offices conduct yearly evaluations of localities. Monitoring is not limited to higher authorities inspecting their administrative subordinates; peer monitoring between provinces and counties, random sampling, and monitoring in the form of experience-sharing meetings are also common methods. The county M&E staff in Guangxi inspected their project jurisdictions three times per month on average. The counterparts at the village cluster level logged 8 times on average, amounting to 9.84 days. Both the frequency and

content of these field assessments have progressed far beyond the prior practice where evaluation was focused on checking against certain nominal targets.26

4) Installation of external, independent monitoring and surveillance. At first, Chinese project staff felt that independent monitoring showed a lack of trust on the part of the WB and that, if it must be done, the activity should be funded separately and not take away from project funding. 27 At the WB’s insistence, independent M&E nevertheless stayed as a prominent component of the project design. The monitoring component, employing external independent agencies, collected valuable, comprehensive data that fed into project evaluation as well as broader poverty surveillance.

The impact of modernized project management lasts far beyond the projects themselves. The current administration of China’s domestic poverty reduction projects, such as some rural infrastructure projects, readily adopt protocols such as cost reimbursement, open bidding, and integrated project planning into their forte. Regular

M&E also has become a routine element. Internal M&E now not only ensures projects stay on their intended courses, but also provides a valuable platform for project professionals and practitionersto exchange knowledge and experiences.

More importantly, independent monitoring during the SWPRP project built the foundation for establishing China’s modern poverty surveillance system. Upgrading poverty monitoring at the national and local levels was in fact an explicit goal of the SWPRP project Poverty monitoring in the 1990s went little beyond infrequent collection of aggregate data by the National Statistics Bureau. However, these nominal indicators were not very helpful for identifying the causes of poverty and devising appropriate policy responses. After building upon the poverty surveillance plan of

the SWPRP project in 1997, the Rural Division of the National Statistics Bureau made significant improvements to poverty surveillance by assembling and distributing comprehensive data to all 15 participating ministries in the National Assembly for Poverty Reduction and Monitoring ( 全国扶贫监测联席会议). These data have become the evidential basis for policymaking not only for the poverty alleviation system but also for the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Civil Affairs (民政部). The staff that participated in the WB’s poverty surveillance became leaders in the field

and played pivotal roles in the 2006 National Agricultural Census.

4.3 Capacity Building

The third aspect of donor influence is capacity building among China’s poverty reduction institutions and professionals. This process took several forms:

1) Formal and informal training. During the SWPRP project, the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development organized 17 international study tours, benefiting 157 staff members from the national office and three provincial project offices. Training sessions on various subjects took place regularly. The SWPRP project held 199 workshops in its ten years of operation, training up to 11,875 project personnel. The first two years of project operation from 1996 to 1998 featured intensive training, followed by regular reviews and supplementary

courses. During the Qinba project, the national project office held 17 international study tours and training workshops and 18 domestic experiencesharing programs. The provincial offices logged 57 training sessions supporting 3,286 professionals.Regular training efforts at the county level wereeven more numerous.

2) Capacity building as learning on the job. As was discussed in previous sections, international donor projects tend to have well-formulated, procedurized project models and management protocols. These protocols, consciously or unconsciously, shape project staff’s perceptions of how a project should be run. The emphasis on monitoring and evaluation, for example, not only trained M&E professionals, but also paved way for establishing China’s very own poverty surveillance system. The rigorous accounting and auditing requirements trained a class of professionals well

versed in international accounting standards. The introduction of the participatory approach brought forth community facilitators and organizers. It is worth mentioning that the CDD approach, adopted in other countries primarily as a project model, also made capacity building its core element in the Chinese context.

3) Professionalization of poverty reduction personnel. The high specificity of most international donors’ projects dictated that specialized professionals are often needed in order to conform to project standards. Institutionally, because project offices at all levels are staffed separately from the existing governmental administration, project personnel bore specialized responsibilities in conducting international poverty reduction projects. Skill-wise, the multidimensional and integrated approach by most international donors greatly expanded the breadth and depth of project work and naturally called for greater division of labor and specialization. This specialization thus provided

for developing expertise in various professional areas.

4) The fourth aspect of capacity building pertains more to administrative institutions than to individual professionals. As the World Bank report, China: Strategies for Reducing Poverty in the 1990s, notes, not having a permanent, ministrylevel poverty reduction agency was crippling for further alleviation of poverty. Policy

recommendations like this played a contributing if not pivotal role in shaping and strengthening the governance system.

Capacity building is perhaps among some of the most common jargon in the field of international development. Although almost all donor programs around the world stress capacity building, they achieve at best varying results. One common problem is that the content of capacity building deviates from the actual needs of the practitioners;

the other is that, even when the training is in fact effective, project staff move on to more lucrative opportunities often far removed from poverty reduction. International donors’ capacity building in China, however, appears to have avoided these two main pitfalls. Many of the former staff at World Bank projects move on to hold important governmental posts in poverty reduction or a related field. Over 10 intermediate and above level staff at the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation, for example, had participated in international donor projects at one point or another.

How was this high retaining rate and effectiveness accomplished? We observe that there are several contributing factors: 1) one is that, throughout the decades, international donor projects remained only a part of much grander poverty reduction endeavors by the Chinese government. This backdrop implies that international donors provide

a platform and training ground for continued advancement in China’s governmental system. When professionals “graduate” from a World Bank project, for example, they face ample opportunities within China’s poverty reduction system itself. Many trained project managers in the Project Implementation Units (or Project Management Offices) were promoted to director-generals in government agencies such as the State Council Leading Group Office for Poverty Reduction.28 2) The governmental directorship also means that training is more likely to be suited to the actual needs of the staff, preparing them for future government endeavors. 3) Professionals derive personal fulfillment from capacity building activities.29

5. Partners: Marry First,Love Later

In the above sections, we have examined three aspects of institutionalized donor impact on China’s approach to poverty reduction. But how exactly did these impacts materialize? What mechanisms drove the process? In this section, we examine the specific ways in which international models interacted with China’s existing policy traditions and institutional environments. We note that the process of initial contact, interaction and eventual synergy and convergence is not without friction and demonstrates several distinct phases. Ultimately, international donors are able to leave a long-term impact on China’s poverty reduction efforts due to the fact that the Chinese government has

remained in the driver’s seat at all levels when collaborating with international players; international projects are integrated into China’s existing institutional and policy frameworks. In addition, the adoption of international practices

has been selective and experimental, scaled up later only with suitable local adaptations. This graduated localization process allows for institutional learning and progressive changes in mentality and norms. These changes serve to

strengthen and enhance rather than replace China’s homegrown approach to poverty alleviation.

5.1 Different Phases, Varying Impacts

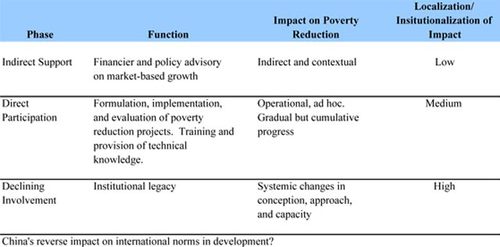

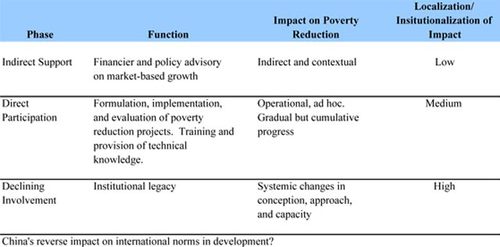

In Section 2, the Overview, we already identified the three stages of donor engagement in poverty reduction in China: indirect support, direct participation, and declining influence. At different stages, the nature of the impact by donors is different. We summarize the evolving patterns of influence in Table 3.

1) Xu calls the period from 1981-1991 one of short-term conflict. Indeed, as the WB’s 2005 evaluation of its assistance strategies in China notes, the initial years of cooperation between China and the Bank were marked by “patient efforts on both sides to overcome cultural differences and mutual misunderstandings or suspicions.”30 The WB did not operate in China’s poverty reduction projects per se; its support tended toward less direct, broader

macroeconomic interventions and policy recommendations. At the time, China was unfamiliar with and remained cautious about the prevailing western approach to poverty reduction and did not actively engage international partners

in program formulation or implementation. Donor impact in this stage remained peripheral to the core of China’s poverty reduction programs.

2) The years from 1992-1999 were marked by short-term, operational cooperation involving international actors directly in project efforts. The SWPRP project was the first experiment for both Chinese and WB practitioners in this cooperative mode. During this period, the WB made localized, focused impact on China’s approach to poverty

reduction mainly through stipulating specific modalities for the formulation of programs and implementation methods. For example, insisting that health and education services stay as principal components of the SWPRP project was a decision within the scope of an individual project. In retrospect, however, it foreshadowed fundamental changes in the Chinese conceptualization of poverty. The “Three Charts and One Picture” method was a highly specific technique even as it marked the germination of a participatory approach in poverty reduction work. As Xu notes, the WB’s impact during this period remained at an operational rather than institutional level since lessons and experiences were

gathered on an ad hoc basis; sedimentation into institutional learning occurred only later.

3) 2000 to present. Discrete changes in project mechanics introduced in the previous phase now serve as building blocks for systematic, institutional innovations. Note that this period coincides with the trend of declining donor influence as a financier as well as source of technical expertise as discussed in Section 2. Put more precisely, donor influence in this period, rather than simple decline, is marked by selective absorption and digestion by China’s local institutional framework. Here we see China, instead of mechanically adopting specific practices, thoroughly adapts them to local circumstances and integrates them into the country’s broad policy mandates. In other words, the previous decade was marked by graduated localization of and institutionalized learning from international practices. The monitoring and evaluation protocols inherited from the SWPRP project, for instance, contributed to the establishment of China’s very own poverty surveillance system.

4) If the last decade was marked by localization and institutionalization, we are now arguably observing a reverse trend whereby China has begun to exert influence on the world of international development. China’s insistence on a

unique path with Chinese characteristics and the success that followed has inspi red the reconsideration of many prevailing doctrines in

Table 3 Patterns of Donor Impact on Poverty Reduction in China

development assistance. 31 Specifically, the Chinese government’s emphasis on economic development as the primary driver for poverty reduction and sequenced policy prescriptions that led this growth to benefit the poor offer important lessons not only for other developing countries, but also for international donors intimately engaged in these nations’ development. Here we observe convergence from two sides: after years of rapid growth, China is now paying increased attention to tempering disparity, protecting the environment, creating social safety nets, and strengthening governance. Note that these areas reflect China’s current development priorities while coinciding with the policy imperatives that donors have been championing for decades in the field of development assistance. International donors, on the other hand, are showing revived interest and increased willingness to acknowledge economic growth as the central theme of development and poverty reduction. Pro-poor growth has become the hottest catch phase in international development in recent years.32 In 2007, the OECD released a policy guidance document on pro-poor growth for DAC donors.33 Possibly inspired by the example of China and other Asian countries, donors increasingly emphasize the importance of agricultural development and productivity in alleviating abject poverty. 34 In addition, there appears to be a revival in infrastructural investments in developing countries. The 2009 World Bank plan to source more than $55 billion within the next three years to support infrastructure projects in poor African countries received overwhelming support from western donors. 35 Whether the move was inspired by China’s infrastructure-heavy development model or to counter China’s extensive foray into the continent - again led by infrastructural investments - these trends signal a possible return to infrastructure as an essential element of development assistance.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to address the precise relationship between China and other donors in development aid broadly. We include the above discussion primarily to demonstrate the fluid forces of influence between donors and recipients. Donor impact in China does not just run in one direction. While China learns and localizes western objectives and approaches for poverty reduction for its own use, donors also gather experience and reassess their thinking in this process. As the title of this section suggests, international cooperation is not unlike marriage. And in China’s case, the marriage did not exactly thrive on love at first sight. From the period of mutual suspicion and tentative scoping (no direct donor engagement in poverty reduction) to making house and establishing business as usual (operational cooperation) and to achieving real convergence in heart and soul (localization and

institutionalized learning), the journey was prolonged and punctuated with numerous trials and errors, negotiations, and compromises. Today, in a monumental year marking the 30-year anniversary of China’s cooperation with the World Bank, both parties have been benefited and enriched their experiences.

5.2 Leadership of the Chinese Government

A healthy marriage is based on equal partnership and mutual respect. The same logic goes for international cooperation in poverty reduction. As we note in the beginning of the section, donor impact on the country’s institutions largely owes to the leading role of the Chinese government. This leadership has several manifestations: 1) Leadership in strategic vision. Since poverty reduction officially became a national priority in the 1980s, China’s policies have consistently focused on driving poverty reduction through economic development. This vision has persisted through all different phases of international cooperation. To the extent donors’ visions may have differed from those of China (e.g. how and to what extent to introduce elements of social mobilization or participation), these gaps were narrowed only through long, tentative periods of experimentation and adaptation. This process not only prevented risky, radical policy changes, but also ensured that the strategic revisions that did occur had sound evidential basis and suited local priorities. These endogenously generated innovations have sustained far broader and more profound impacts than abrupt policy transplants would have. In fact, as was already discussed in the previous section, China’s successful, homegrown strategies are now calling into question some of the traditional

wisdoms in development practices. As Wang summarizes, a key element of China’s success in managing and utilizing development aid is the adherence to a long-term development plan and to the consultation process it entails. Donor projects are only selected if they are consistent with China’s long-term development and poverty alleviation plans as well as local conditions.36

2) Leadership in the governance structure. Structurally, the strong executive capacity of the Chinese government provided the necessary vehicles not only for policy implementation, but also for the diffusion of innovative ideas.

International project offices are not ad hoc administrative units but an integral part of China’s governance apparatus with lateral as well as vertical linkages. Project officers were paid at a rate on par with their governmental counterparts

and remained internal to the “system” and not external as hired by donor agencies. 37 The adoption of project offices into China’s governmental apparatus has achieved mutually enforcing effects: one, it contributes to efficient allocation and utilization of resources when donor operation becomes part of the poverty reduction planning. As Wang notes, this setup reduces the risk of a “principal-agent problem” in a delegatory relationship. Two, donors have the potential to achieve system-wide impact since they act from inside the governing institutions. As was previously pointed out, donors’ capacity building in China has been so successful partly because the practitioners it trains can benefit from the skills and carry them over to other posts in a rapidly developing and maturing poverty reduction system. In addition, individual project experiences can be scaled up relatively easily because a widespread administrative network is already in place. Indeed, China’s cooperation with international donors was able to move from an ad hoc, operational basis to achieving institutional impact precisely because the government possessed cohesive leadership

and a strong executive structure. In other words, they held the system together and allowed for graduated dissemination of new ideas and approaches.

3) The Chinese government’s leadership role is also reflected in coordination among multiple donors. Donor coordination and harmonization have long been a challenge for recipient countries and a large number of academic studies have found evidence of the potential hazard of aid proliferation. 38 Acharya et al. find that donor proliferation significantly reduces the benefit of aid by increasing what economists call “transactions costs,” a term that refers to the additional costs of administration, coordination, and negotiation that come with more donors. The Paris Declaration is centered on donor harmonization, calling for a more concerted approach to aid and better coordination among donors and greater ownership of the development process by recipient countries. The Chinese experience in aid management attests to this very vision of the Declaration.

In China, the active leadership of the state plays an important role in mitigating heterogeneous donor preferences. As was described in Section 3, by the beginning of the reform, China had already established a management system for development assistance, led by the Ministry of Commerce. Donor participation in China’s

development process (in the area of poverty reduction or otherwise) is filtered through a guided consultation process as described by Wang: during the preparation of the five-year development plans, the planning agency consults

with the ministries and localities and reconciles their needs with the national plan. The “priority sectors” identified are subsequently presented to international donors for support. MOFCOM initiates discussions with bilateral and multilateral donors primarily on grant projects while the Ministry of Finance serves as a window agency for international financing institutions including the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. In short, the Chinese state’s leadership role in managing development aid precludes the need for costly ex ante reconciliation of donor demands. Instead of having donors take the initiative, China knew what it wanted and matched those wants to what donors had to offer.

5.3 Trade-Off in Possessing Strong State Leadership?

In this section, we have discussed the phasing and mechanisms of donor impacts in China. The decisive mechanism that shapes the trajectory of interaction between China and international donors, we observe, is the effective leadership role of the Chinese state. This role, as was shown in analyses above, exerts several profound

implications: 1) A strong leadership rooted in longterm planning ensures a steady, controlled pace in introducing changes to the existing system, allowing opportunities for experimentation and adaptation. 2) The integration and internalization of donor resources facilitates systemic, albeit gradual, transformation of China’s approach to poverty reduction. Changes occur endogenously. 3) The state’s robust leadership significantly ameliorates the challenge of donor proliferation and coordination.

We should note, however, that a strong state leadership could also bring difficult tradeoffs. According to the China-DAC Study Group, donors find that coordination across window agencies is difficult due to vested interests, high institutional barriers, and capacity constraints within some ministries.39 In other words, donors, being part of China’s governance system, face many of the same institutional limits as domestic actors. In China the vertical chain of commands (tiao) has always been more compelling than cross-sectorial, lateral relations (kuai); this feature remains salient in international cooperation. 40 Another telling example is the repayment responsibility system for

international loans. As we note in Section 3, in China, only the center has the authority to negotiate and conclude international loan contracts. The amounts are then re-loaned, often with an added interest premium, to the lower levels. However, the ultimate repayment responsibilities lie with the localities. This system plays an important role in motivating the localities to utilize funds and choose projects judiciously, but it also de-motivates counties from investing in projects without immediate economic returns and, in the event of bad loans, the resulting fiscal deficits can become sizable burdens for counties that are just emerging from decades of poverty.41 Although the drawback of this unique repayment system is widely known among donors and China’s policymakers, revision has been slow partly because the system itself reflects the longstanding tension between the center and localities in China’s fundamental governance structure: a unitary, authoritarian state withsubstantial degrees of economic and fiscal federalism. Competition for resources is as implicit as it is palpable across various levels and sectors of the government.

6. Implications for China's Overseas Poverty Reduction Cooperation

This paper so far has focused on development partnerships in which China is a recipient. As China boosts its investments and development assistance in other developing countries, it is time we ask: to what extent can China’s experience as a recipient be transferred to its poverty reduction and development cooperation overseas?

The answer will require more rigorous research. Here we only hope to raise the question and propose some preliminary thoughts, based on the analyses in this paper, which can perhaps spur more discussion among scholars, policymakers, and the international development circle at large. If there are universal themes in our study that speak to China as much as to other developing nations, they are the following:

First, the relationship between donors and recipients is dynamic and fluid. In China, the role of international donors evolved from financiers to policy advisors, to practitioners in project operations, and finally to a role with less direct involvement but significant legacies in shaping institutions, human capacities, and repertoires of concepts and ideas. Is this sequencing necessary for successful donor intervention? Is it sufficient? As China contemplates its engagement today with African, Latin American, and Southeast Asiancountries, should we serve primarily as financiers for broad economic growth and infrastructural improvement, policy advisors in macroeconomic management or sectorial development, project operators in microscopic interventions, or all of the above? As countries fall on a diverse spectrum of development, what varying types of interventions and support help them the most in poverty reduction?

Second, the single most important factor that has shaped donor engagement in China is perhaps the strong leadership of the Chinese government. The foundations of a functioning state with a willful leadership already existed even as China first opened its door after decades of political turmoil. The same may not be said about many of the