2012.02-Working Paper-Chinese state owned MNEs in AfricaImpact on development and poverty

Chinese state owned MNEs in Africa: Impact on development and poverty reduction1

Huaichuan Rui

Abstract

This paper examines the development implications of Chinese state owned enterprises’ (SOEs) direct investment and other engagements in Africa. By examining Chinese SOEs’ wide range of activities in Africa in general and the Chinese National Oil Corporation (CNPC) and other Chinese SOEs’ investment in Sudan in particular, this paper highlights how positive progress on the development of host countries was achieved. The development progress provided a foundation for further poverty reduction in the host countries. The fundamental reason for the positive progress was that the Chinese state owned MNEs possess capability and strategy which can better fit the institutional environment and match the demand of African host countries. This demonstrates that the foreign direct investment (FDI) of a developing country can make positive contributions to development particularly in developing countries, due not only to its capacity appropriate for developing countries, but also to its strategies and mindset more adaptable to the development needs and institutional environment in the host country. However, there are fundamental questions on if we can fully ascribe Africa’ recent growth to China’s contribution and if such growth will be sustainable. In addition, negative impacts of China’s engagement on Africa’s growth are also discovered. Key words: foreign direct investment (FDI), development, poverty reduction, multinational enterprises (MNEs), state owned enterprises (SOEs), China, Africa, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC)

1. INTRODUCTION

The past decade has witnessed China’s substantial increase of its investment into Africa. Its annual investment flow into Africa was $20 million only in 1997 and$75 million in 2003, but rose to $317 million in 2004, $392 million in 2005, $520 million in 2006, and then more dramatically rose to $1,574 million in 2007, $5,491 million in 2008, $1,439million in 2009 and $2,112 million in 2010 (MOC et al., 2007, 2008,2009, 2011).A World Bank source, however,estimated that the figure was less than $1 billion per year before 2004 and over $7 billion per year after 2006 (Foster et al., 2008). If this estimation is accurate, China may account for well above 10% of total FDI Africa received every year. In terms of value, oil, mining, and resource-related projects accounted for 28% of China’s total investment in Africa. This might be the reason why China’s investment relationship with Africa is described as

“dominated by extractive activities” (Jenkins and Edwards, 2006, p. 16). However, this claim does not reflect the whole picture of China Africa relationship. China now ranks as Africa’s secondlargest trading partner, behind the United States and ahead of France and Britain. From 2002 to 2003, trade between China and Africa doubled to $18.5 billion. It then jumped to $73 billion in 2007, $106.84 billion in 2008, $129 billion in 2010, and $160 billion in 2011, all record high figures (MOC, 2010, Sun, 2012). China is also deeply involved in Africa’s infrastructure construction. China’s comprehensive presence in Africa via investment, trade and aid has generated, and will continue to generate, considerable impact on the poverty reduction of host countries. Africa is the home to 300 million of the globe’s poorest people, presenting the world’s most formidable challenge for development. Traditional policies to promote development such as aid and trade are considered unsuccessful (Birdsall et al., 2003; Easterly, 2009), while FDI from developed countries had been stagnant for decades up to 2005 (UNCTAD, 2007). However, the recent dramatic rise of FDI from developing countries has brought both hope and concern for Africa’s development.FDI inflows to Africa rose from $29 billion1 in 2005, to $36 billion in 2006, $53 billion in 2007 (UNCTAD, 2008) and to another record high of $88 billion (UNCTAD, 2009, p. 42), against the background of financial crisis. According to the annual investment report of the United Nations (2007, 2008), the major driving force behind this rising FDI inflow to Africa was precisely China.

This paper will focus on the impact of the Chinese state owned enterprises (SOEs) on development and poverty reduction of Africa. In detail, it examines how the Chinese SOEs’ activities, mainly FDI and contracted projects, impact on the development and poverty reduction in their host African countries. This research focus is based on

the following considerations. Firstly, FDI by developing countries is considered to have particularly important implications for the development of host developing countries (UNCTAD, 2006). The motivations, locational advantages sought, and competitive strengths or ownership specific advantages of developingcountry multinational enterprises (MNEs), which carry out FDI or trade, differ in several respects of MNEs from developed countries (UNCTAD, 2006) and therefore may also generate different impact on development. Secondly, China’s FDI in Africa

may have particular implications to development. FDI is generally perceived to have more direct impacts on development than trade and aid 1 $ refers to US$ in this paper. because FDI brings not only direct but also

indirect impacts on host countries as demonstrated below. Secondly, FDI in resource rich countries is particularly controversial for its implication to development. Rich natural resources could bring development, evidenced by both

developed countries including Australia and Canada, and developing countries including Botswana, Chile, and Brazil. At the same time, resource booms may also become a curse rather than a blessing (e.g. Karl, 2007; Sachs and Warner, 2001; Mehlum et al., 2006). Examples often cited to support this argument include Angola, Nigeria, Sudan, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Congo. In the case of Chinese resource seeking FDI in Africa, considerable speculation also rises on whether China is implementing a new colonialism in Africa, through which resources will

be extracted but poverty left unchanged, or even worsened (Broadman, 2007). Arguments were also heard that China’s involvement in Africa was not aimed at local development and may produce the opposite (e.g. International Crisis Group, 2007). Specifically, the sharp decline in commodity prices and the slowdown in global economic growth since 2008 may signal a possible reversal of the trend towards rising FDI in Africa, breaking the region’s consecutive growth for several years (UNCTAD, 2009). Thirdly, Chinese SOEs are also heavily involved in contracted projects such as constructing dams, bridges, roads and so on. These projects have generated considerable impact on host country in terms of changing the capacity and environment of the infrastructure in host countries. Finally, 66% of China’s OFDI stock by the end of 2010 was made SOEs (MOC et al., 2011). Similar as this trend, SOEs have been the dominating power and playing significantly important roles in Africa.

The paper is based on the data collected by the author from 16 fieldworks in both Africa and China between 2005 and 2011. During the fieldworks over 100 interviews were conducted in both home and host countries across the SOEs involved, their related partnering firms, government officials, local communities in host countries and international research institutions. This paper is organized as follows. Section two sets up an analytical

framework to display the most important determinants of FDI’s impact on poverty reduction. Section three provides a general overview of the Chinese SOEs’ activities in various areas and their impact on poverty reduction in Africa. Section four provides a detailed case study on how Chinese SOEs activities impact on poverty reduction in

Sudan, a typical African country. Section five will conclude the paper by demonstrating how the Chinese SOEs’ activities and the host institutions interact, and how they together impact on the poverty reduction of Africa. It will also provide the implications on Chinese SOEs in Africa.

2. FDI AND DEVELOPMENT: THE ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the key propositions of the dominant neoclassical development paradigm were based on the underlying premise that the goals and characteristics of the developing countries were fundamentally similar to those of developed countries; government’s useful role was seen as limited; and the extent and quality of institutional infrastructure and social capital were largely neglected. Developing countries were expected to replicate the institutions and economic policies of the wealthier nations in order to advance their development. Meanwhile, development was also more concerned about economic growth and increase of income (Meier and Stiglitz, 2001).

In such proposition, trade and FDI are expected to be effective for development in developing countries, as they are proved to be effective in many other countries. Empirical evidence, however, provides mixing and debatable results (Caves, 1996; Meyer, 2004). The reality was disappointing as many developing countries failed to promote development through attracting FDI – despite (or perhaps because of) significant policy adjustments designed to appeal to inward investment, whose flows remained predominantly within the rich triad’ of North America, Europe and Japan.

The new paradigm of development since the late 1990s advanced the argument that institutions form the essential incentive structure for development (Dunning and Lundan, 2008). Institutional theory demonstrates that different institutional conditions will lead to very different development paths even with the “same” FDI and

MNEs. The institutional environment consists of political and legal systems, rules, policies,

regulations and conventions, which are devised or evolve over time to constrain social agents and reduce the uncertainty of social interaction (North, 1990). A MNE is a governance system performing a collection of value-adding activities under unified coordination and control, but institutions affect these activities while MNEs influence institutions too. Meanwhile, empirical researches also provide profound evidence on how institutions make FDI’s

impact on host country very differently (e.g. Boudier-Bensebaa, 2008).

In addition to the appropriate form of FDI and institutional conditions, MNEs’ capability and strategies also relate to the transformation of FDI into development for a host economy. The international business (IB) perspective suggests that MNEs go overseas for their own interests but could make various contributions to host countries

given their superior ownership advantages or capabilities over local firms (Dunning, 1980). MNEs are considered to make the contributions through their direct and indirect impacts on host countries. Direct impacts include those on the structure of trade and the balance of payments, on technology transfer, on local market structure, on the level of employment and human resource development, and on average labour productivity and wages. In addition, there are indirect impacts which impinge on the local firms in the host economy. These may be experienced either through linkages with MNEs, or through increased competition and knowledge spillovers to the local economy (Dunning and Lundan, 2008, p. 551). Conversely, however, MNEs have been criticized for inducing failures to enhance local firms’capability because of affiliates’ greater efficiency than local firms; using technology that is not always appropriate for local circumstances, creating merely low-wage jobs, and (ab)using their powerful political and economic position in host countries (Kolk et al., 2006).

There is a particular concern over whether developing country FDI can deliver local development because the investing companies do not possess the ownership advantages that western MNEs do (Mathews, 2006) and may be

also less committed to international human rights and environment standard. However, there is an opposite view which argues that developing country FDI have particular implications for host developing countries (e.g. Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008; UNCTAD, 2006; Yeung, 1994). Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc (2008) provide an empirical analysis to argue that developing country MNEs tend to be less competitive than their developed country counterparts, partly because they suffer the disadvantage of operating in home countries with underdeveloped institutions. However, this disadvantage can turn to be an advantage when both types of MNE operate in

countries with ‘difficult’’ governance conditions, because developing-country MNEs are used to operating in such institutional conditions.

The implication of the above literature is that, MNEs have potential to promote development which includes poverty reduction, butthis depends on not only MNEs’activities but also capacity, strategy and an appropriate host institutional arrangement.

3. OVERVIEW OF THE CHINESE SOEs IN AFRICA

3.1 Main characteristics

The following overview on the characteristics of the Chinese engagement in Africa in general and of the SOEs in particular could shed light on why the Chinese presence in Africa has attracted worldwide attentions, both positively and negatively.

First, China’s outwards FDI is overwhelmingly concentrated in Africa. China’s OFDI stock was still extremely small, which accounted for 1.6% of the world total by the end of 2010 (MOC et al. 2011). It is concentrated in developing countries, given that only 9% of the OFDI stock went to Europe and North America by 2010.According to the Statistical Bulletin of Chinese OFDI produced annually by the Ministry of Commerce, China, the two largest destinations of China’s OFDI are Asia and Latin America. However, further investigation could find that around 70% of China’s OFDI in Asia actually went to Hong Kong and an even higher percentage of OFDI in Latin America went

to Virgin Island and Cayman Island. Considering that Hong Kong is part of China and OFDI in both Virgin and Cayman Islands is for tax avoid purpose, we have to admit that China’s most active and “real” OFDI outside China is indeed in Africa.

Second, the Chinese are engaging in a wide range of industries and businesses in almost all African countries. Projects and activities undertaken by Chinese SOEs in Africa are across a wide range of industries, but concentrate in a few, namely resources and the related, telecommunications, construction, service sector such as hotels, restaurant and tourism, banking, logistics, trading and manufacturing. (1) Resource sector: holding an obligation to fulfill national tasks with cost the least of considerations, although cost consideration becomes more imperative.

Examples are the three largest oil and petrochemical firms. Sinopec, CNPC and CNOOC are the largest Chinese MNEs in terms of FDI stock by 2010 and all operate in Africa actively. Largest mining/metal firms such as Chalco,

Minmetal and Sinosteel all among the top 50 Chinese MNEs. (2) Telecommunication sector: being impelled by a fierce competition in domestic market and encouraged by a‘go out’’policy on the one hand and a need to transform SOE systems on the other, e.g., Telecommunications firm like ZTE is among the top players in the global market. (3) Banking and financing sector: this is the fast growing sector with frequent aggressive acquisitions made by Chinese state banks such as Bank of China (BoC) and China Industrial Commercial Bank (CICB).The typical

case was CICB’s 20% share acquisition of Standard Chartered Bank in South Africa. (4) Construction and infrastructure sectors: a large number of large, medium and small are all working hard in Africa. The largest one is China State Construction Engineering Corporation, which has been very successful in Algeria and other African

countries. Sinohydro is the largest dam constructor of China and has become the key player in the world’s dam construction industry. It has completed many important dam or related projects including the second largest dam built on River Nile - Merowe Dam. the second largest dam built on River Nile. Medium ones such as Jiangsu International, Shanxi Construction Engineering and China Wuyi, three provincial level MNEs with local government support. They have also completed many high profile projects to meet local demands. For example, Jiangsu International built up the large and modern shopping mall in Kenya while Shanxi Construction Engineering completed the challenging project to construct the National Stadium of Cameron which involved new technology and material. (5) Logistic sector: COSCO and Air China are the top players which have been working effectively to open new markets in Africa. (6) Service sector: Numerous firms in this sector to provide whatever demanded services from both Chinese companies and local people. Zijin is a good example in this category. It used to provide services to large SOEs such as Sinopec by assisting expatriates’ eating, living, visa, and so on. With accumulated experiences this company has grown into a large state owned MNE by providing services in a wider range of business including running hotels and restaurants. These projects have changed the life style and improved the living quality of local people.

Third, despite the wide range of business involved in Africa, the Chinese are often viewed as primarily resource seekers. They came to Arica for extracting energy and mineral resources, in which many African nations are richly endowed but from whose exploitation few have benefited, especially when reserves are tapped by multinational

enterprises. They are among the major new players in the Africa resource sector, although old players such as Shell and BP have been in the continent for more than a century. Among the new players, China is certainly the largest one in terms of its investment amount, projects involved and outcome shared.

Fourth, the Chinese SOEs are the major investor or contractors of most of the large projects in Africa. The Chinese government plays a significant supportive role in Chinese SOEs’international expansion in Africa. A large

proportion of Chinese state owned MNEs won contracts due partially to state bank support or excellent diplomatic relationship between China and the host African government. Many state owned MNEs under this research received

financial support from the state bank in the form of loans or other modes of support in one or some of the projects they have completed. Some companies revealed that as high as over 80% of their overseas projects were won based on the state bank loans. Although their capabilities of conducting the projects were important to win the contracts, it is a question if they can definitely win the contract without the support of the loan provided to them (as exporter’s credit scheme) or to the project owner (as borrower’s credit scheme). Many Chinese SOEs are indeed fast learners.HPEC, for example, won its earlier projects by having state bank loan support but is able to obtain more contracts afterwards by demonstrating its completed projects with good quality. But we also find that many Chinese firms rely on government support and pay inadequate attention to their learning and improvement.

Finally, China has replaced the traditional FDI and trade partners of Africa such as the US and UK, become the top investor or trading partner of many African countries. In contrast to the US and EU, China is perceived to have detached its commercial agenda in Africa from wider considerations of democratic institution-building, improvement of public-administrative and corporate governance, promotion of civil society and reduction of corruption. In so doing, it has been accused of blunting US and EU’s wider social and political development agenda for Africa, and even of forcing the EU to retreat from that agenda in order to avoid economic disadvantage (EC, 2008; UK House of Lords, 2010). However, for many Africa countries, China’s rapid economic growth since the 1980s offers them a substantially different development model from that suggested by the US and Europe, with their heavy conditionality on free trade and governance requirements but local development goals were sidelined (EC, 2010).

3.2 Unique capabilities of the Chinese SOEs in Africa

Capabilities are prerequisite for MNEs to contribute to the development of host countries. Conventional multinational firm theories suggest firms internationalize in order to exploit their“intrinsic”competitive advantages such as original product invention, high-end product technology, and well-known brands (Bartlett et al., 2004, p. 4).

My research discovered that many Chinese SOEs operating in Africa do not possess these intrinsic advantages, but have unique capabilities, on comprehensive or niche technology, unique techniques, financing, lower cost, or better service (e.g. shorter time period to finish projects; customization; taking risky business etc). In detail, the Chinese state owned MNEs in Africa particularly enjoy the following capabilities:

Making innovative products for niche markets.The founder of Lenovo, Mr. Liu Chuanzhi, stated frankly in June 2006 in his interview with me: “We do not have original product technology, but applicable technology and niche market inventions”. Many other interviewees in state owned Chinese MNEs made similar claims. They focus on applicable technology but not original technology based on the belief that R&D on original technology was too time consuming and not necessary if that technology can be acquired from international market. The niche market and

applicable technology have proved to be in high demand in China as well as other developing countries. For example, CNPC and Sinopec have accumulated rich experience in exploring and developing oil and gas in China which can be applicable in countries with similar mineral geographical background in Africa. The nonmarine petroleum geological technology put an end to the “China is poor in oil” argument and led to discoveries of large oil fields within China. The application of large heterogeneous sandstone reservoir development technology, separate zone production, water-cut control, and tertiary recovery technologies stabilized the production of the Daqing oilfield at around 50 million tons per year for 27 consecutive years, a record for the world petroleum industry. CNPC also owns technologies for the commercial development of small faultblock reservoirs (Zhou, 2006). Such niche market technologies proved to be important for these companies to win competitive advantages in not only China, but also Africa. As shown below in the case study, CNPC made breakthrough in Sudan based on these technologies.

Tremendous cost advantages in manufacturing, labour, equipment, and services. Interviewees from all companies confirmed that low cost labor and equipment is a large advantage. For example, the cost for an engineer in Chinese companies could be one third or even one fifth of that in western companies. Low cost advantages also enable the Chinese companies to provide the most flexible and effective services to customers in Africa. In doing so the Chinese firms certainly benefit from the comparative advantage that China possesses. Having an economic, reliable, and fast responsive domestic supply chain of the goods and services that overseas firms demand has become the most critical resource for the Chinese firms to establish production bases, trade goods and services, win contracts and sub contracts. As the subsidiary of one construction company stated: “The cost of equipment and facilities for construction companies account for more than one third of total project costs. The cost of our equipment and facilities is normally one third or even one half lower than that of our rivals, which are western MNEs who have been in Kenya’s market for decades …… The equipment we use in our projects was purchased by our headquarters in China and then transported to Kenya” (Subsidiary Head of the China Wuyi, interviewed on 21 June

2009, Nairobi). Meanwhile, the parent firm explained how it supported its overseas subsidiaries as: “Our headquarter works hard to ensure the subsidiaries to have the most advanced equipment because high quality equipment is more able to provide higher quality of construction work while also having longer service time so as to save cost. … We have long term reliable suppliers in China but sometimes we also purchase from whatever channels if that is required by the subsidiary urgently” (Corporate Head of China Wuyi, interviewed on 13 August 2009, Fuzhou).

Not surprisingly, most contracts won by Chinese construction firms such as China Wuyi were benefited from the lower cost of labour, materials, equipment, services and eventually the total bidding price. For African host countries, lower bidding price from the Chinese was a huge bargaining power to force other bidders to low their asking prices. Eventually the host countries saved cost on their projects and maximized the benefits of limited capital. China Wuyi has won several high profile projects in constructing Kenya’s military airport, first class roads, and hospitals and houses dedicated to poor people. The interviewee of the Department of Roads claimed that “the Chinese companies helped us to save project cost so we could do more things with limited money” (interviewed on 22 June 2009, Nairobi).

Unique corporate management system. More and more Chinese MNEs, large or small, have developed innovative and unique management systems. Some common features are highlighted here: (1) A highly centralized management system had been established in many Chinese state owned MNEs which is capable to make quick

decisions to respond external environment change. In large SOEs with the government mandate top leadership can make long term commitment in activities such as natural resource assets acquisition or sacrificing current profits in order to return long term close relationship with the host country. This is contrast to the Western style democratic decision making process in which shareholders may be short-sighted by maximizing their short term benefit by sacrificing long term commitment. (2) Effective management system had been established to integrate both scientific

management of western style and innovative management style suitable for their own companies. For example, both CNPC and China Wuyi spent a fortune to purchase and adopt world class management systems. Meanwhile, these

companies established many innovative systems to meet the company feature as well as customer’s demand in host countries. (3) Corporate culture was to advocate employees’loyalty and commitment to the mission and

interests of the company. CNPC’s exploring experts admitted that discovering oil and raising China’s national flag in the oilfield they operated was a key source to encourage them to work to their limit. A senior expatriate who pioneered the exploration in Sudan and also worked in many other countries recalled (2010), “my feeling was

beyond the expression when seeing our Chinese flag standing in the oilfield”. Extending working hours and sacrificing holidays to catch up deadlines for customers are common in almost all the companies.

Effective marketing and service. Chinese firms are able to integrate marketing strategies and techniques of both Western style and Chinese origin. For example, ZTE has become one of the few top players in telecommunications in many African countries. Its marketing is regarded as one of the most effective in China. On the one hand, it respected the“international rule”and regards every international telecommunication exhibition as the major channel of demonstrating and advertising ZTE’s products. It also heavily relies on localization strategy by employing local talents to meet the local customer demand. In ZTE’s subsidises in UAE and Kenya, majority employees were local. On the other hand, ZTE made the best use of guanxi strategy: it had set up subsidiaries or representative offices all over the Africa to allow its marketing staff to be close to the clients, and more importantly to understand the

specific demand from the poor, i.e. promoting new schemes to allow local poor people to use mobile by using techniques that allowed the rich receivers to pay the bill or call free in the evening. Local interviewees said that it was Chinese telecommunication companies’ entry that allowed them to be able to use mobile phones: one was

that the Chinese brought in competition so that existing MNEs like Eriksson had to reduce the tariff; another was that the new schemes were set up for particular consideration of the poor (interviewed in April 2008, Sudan).

The capabilities that the Chinese MENs possess, as shown above, has facilitated them to win contracts or establish new projects, and also provided a foundation for them to be able to benefit the poverty reduction in Arica. As a result, Chinese state owned MNEs were able to invest in resources, manufacturing, services, agriculture and other sectors, which stimulated the host country development. They were also able to win numerous projects and built up the most challenging dams, bridges, ports, power plants,transmission lines and railways and road. As the report published by the World Bank (Foster et al., 2008) admitted, China has been the major force of Africa’s infrastructure investment and development during the last decade. The following section will provide a detailed case to illustrate how Chinese state owned MNEs enhanced the development of the host country Sudan.

4. CASE STUDY OF THE CHINESE SOEs IN AFRICA

Sudan is a typical case for illustrating how Chinese SOEs impacted on the poverty reduction in Africa, because not only Sudan is the largest African country (before its separation with the Southern Sudan in 2011) but also Chinese SOEs engaged in a wide range of businesses from resources and infrastructure to services and agriculture. Data collected show that a significant impact has made on Sudan’s poverty reduction since China’s recent engagement started in 1995.

4.1 Chinese engagement in Sudan

Poverty has been a consistent challenge for Sudan. Its per capita GDP was US$38 in 1997, when CNPC started its oil investment in Sudan. Physical infrastructure is generally inadequate. Institutions are among the most diverse. At the same time, the country is among the wealthiest in terms of natural resources, not only rich in oil, but also minerals, water and agricultural land. It has substantial potential for rapid infrastructure, industrial and service development. This provides enormous business opportunities for local firms and MNEs. FDI in Sudan’s oil industry can be traced back several decades: oil majors like Chevron explored for hydrocarbons but eventually gave up due to civil war and failure to meet the demand from host government to speed up oil extraction.

China’s engagement in Sudan started as early as the 1970s under Chairman Mao’s regime, mainly providing aid and loan for non-commercial purposes. China provided a total of US$ 89.3 million in aid and loans to Sudan in the 1970s and 1980s (Ministry of Finance, Sudan, 2008), when the Chinese were still extremely poor. The

bilateral relation was cooler during the 1980s when China’s top leadership shifted its policy to focusing on domestic development. In the early 1990s it was the Sudanese government that initiated a renewal of relations with the Chinese2. This led to an unprecedentedly close commercial relationship between the two countries. While

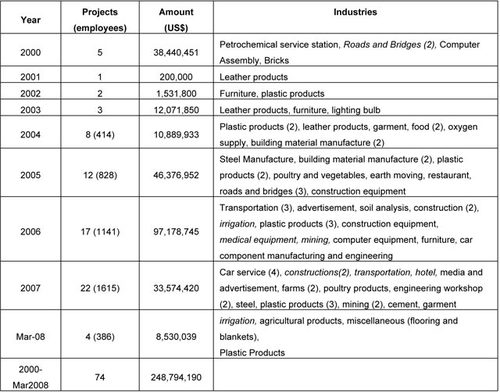

direct investment by Chinese non-oil firms between 2000 and March 2008 was US$249 million excluding oil investment (Table 1), bilateral trade volume between Sudan and China rose from US$103 million in 1990 to US$9.707 billion in 2007 (Central Bank of Sudan, 2008). The accumulated aid and loans rose to US$23.47 billion by 2006 (Ministry of Finance, Sudan, 2008). In 2010 China was Sudan’s largest trading partner while Sudan was China’s third largest trading partner in Africa. The first delegation invited by the Sudanese government to explore investment opportunities visited Sudan in 1995, which included Zhong Yuan Oilfield. CNPC stepped in the negotiation at a late stage.

Table 1 Chinese direct investment in the Sudan (Non-oil Part)

Source: Ministry of Investment, Sudan (2008). Interpreted from Arabian language and then categorized by the author with assistance of her colleague.

Notes: (1) Data for China’s investment in oil and petrochemical are not shown in this table. They are highly confidential and

managed by Ministry of Energy and Mining, the Sudan. (2) Employee numbers were not available until 2004.

4.2 CNPC invests in Sudan: capability, strategy and mindset

CNPC is China’s largest producer and supplier of crude oil and natural gas, accounting respectively for 57.06% and 79.5% of China's total output in 2010. It is also a major producer and supplier of refined oil products and petrochemicals, second only to Sinopec. Globally, CNPC started its foreign expansion in 1993 but made no significant progress until 1997, when it acquired large stakes in Kazakhstan, Sudan and Peru. By 2010 CNPC had about 80 overseas projects in 29 countries. It is now ranked 6th among the world's top 50 petroleum companies.

CNPC’s capability is closely related to its dominant position in China’s oil and gas industry, inherited from two major restructurings within China’s oil and petrochemicals. Before the 1980s, China’s entire oil and gas exploration and production was controlled by the Ministry of Petroleum Industry (MPI). In 1988, the State Council dissolved the MPI but established CNPC to take control over former MPI assets. The assets CNPC owned then were mainly upstream, as Sinopec was to control the downstream assets. Such a situation was not changed until 1998, when both companies were allocated assets covering upstream and downstream.

With over fifty years' development, CNPC has acquired some unique, practical and advanced petroleum technologies, which backed the development of the Chinese petroleum industry. The non-marine petroleum geological theory put an end to the "China is poor in oil" argument and led to discoveries of large oil fields within China.

The application of large heterogeneous sandstone reservoir development theory, separate zone production, stabilizing oil output by controlling water-cut, and tertiary recovery technologies, stabilized the production of the Daqing oilfield at around 50 million tons per year for 27 consecutive years, a record for the world petroleum industry. CNPC also owns technologies for the commercial development of small fault-block reservoirs (Zhou, 2006). These unique technologies, theories and practices have a good application in CNPC’s overseas projects. In Sudan, for example, by using specific theory and technologies for passive rift basins and under-explored basins, which were

developed in China, CNPC made a discovery of 5 billion barrels of oil in Block 3/7 of the Melut Basin in Sudan, a basin abandoned by western companies (Interviewed the chief commander of CNPC Nile Ltd in Sudan, 21 April 2008, Khartoum). Another important capability which assists CNPC to win contracts is its ability to provide products and services at a lower price or in unusual circumstances, as in extremely underdeveloped and conflict-torn countries like Sudan. The lower price in turn was based on cost advantages, with costs a third less than the Western bidders in some cases. This is particularly attractive for host developing countries with “too little money for too many unfulfilled projects” (anonymous interviewee, 24 April 2008).

MNEs’ capability indicates the potential contribution to the host country, but it is argued that oil MNEs normally have a global strategy which impedes local responsiveness (Yamin and Sinkovics, 2009) and MNEs lack of mindset to serve the poor (Prahalad, 2010). In the case of CNPC, there is a clear long term of becoming an integrated internationally competitive energy corporation. To serve this global integrative strategy, capital, equipment, and human resources are moved around the major investing sites of CNPC in order to maximize efficiency and profits. However, attention is also paid to local responsiveness, evidenced by examples such as establishing the refinery and petrochemical industries so as to allow the host country to climb up to the oil industry value chain (shown below).

CNPC’s local responsiveness was also determined by its strategic intent of internationalization (Rui and Yip, 2008). CNPC goes overseas not only to exploit internal advantages but also use institutional advantages to overcome ownership disadvantages such as lack of international management skills, brand, global oil and gas reserves, and some specific technologies. CNPC’s institutional advantages include the Chinese government’s support from both finance and diplomacy. As the investment in Sudan was initiated by governments, CNPC was therefore expected to be locally responsive in order to maintain the close relation between the two countries. On the other hand, when resource nationalism makes global competition for oil reserves more intense, CNPC has to follow

international standards of technology, health and safety and corporate social responsibility in order to get contracts, as the highly-prized Production Sharing Agreements (PSAs) use increasingly internationally standardized terms.

On 29 November 1996 the four partners from China, Malaysia, Canada and Sudan signed with the Sudanese government on a draft PSA for the exploration and development of Block 1/2/4 oilfield. In 1997 the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company (GNPOC) was established as the Consortium, formed by CNPC, Petronas, Talisman

Energy which sold its share to ONGC in 2003, and Sudapet (representative of the host government). Based on the shares they held, which is 40%, 30%, 25%, and 5% respectively, CNPC became the operator of GNPOC. By 2008 CNPC had invested in seven projects in Sudan, including four oil exploration and development projects, one

pipeline, one refinery, and one petrochemical project, worth an estimated US$5 billion (Interviewed at Ministry of Energy and Mining, Sudan, 5 May 2008, Khartoum).

4.3 CNPC invests in Sudan: direct and indirect impacts

According to the explanation on direct and indirect impacts in the second section, we summarise the following direct and indirect impacts of the CNPC’s investment on Sudan’s economy and society.

4.3.1 Direct impacts

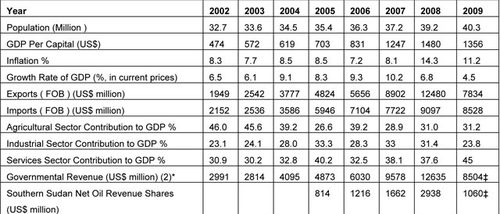

The direct impacts that CNPC’s investment have made on Sudan are best represented by the huge revenue the country has received. The first barrel of oil was produced in and then exported from Sudan in 1999, which fortunately enjoyed a consistently rising price until 2008. Sudan’s revenue rose substantially year by year between

2002 and 2008 with the increasing oil output and price (Table 2). My follow up interviews in May 2010 regarding the declining global oil price and its impact received important information. Sudan was relatively less impacted by the dramatic price falls because its oil exports were signed as long term contracts in which the oil price was not to

follow global market prices but gradually increased annual prices. This ensured the stability of oil income.

Table 2 the Sudan economy in figures 2002-2009

Sources: Central Bank of Sudan, 2008, May 2010.

Notes: * Converted from Sudanese Dinar (SDD) at US$1= 250 SDD; ‡ Estimates.

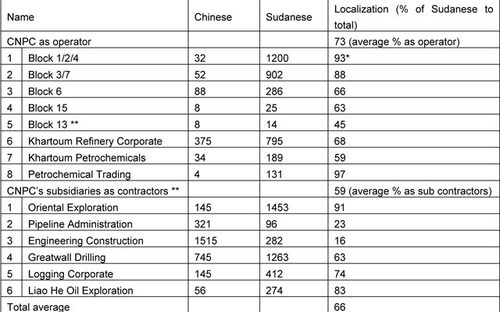

Another direct impact is the employment and training provided for locals. Employment localisation and training has been kept as a central issue and paid particular attention during over ten years’of CNPC operation in Sudan.

Three major reasons can be identified. One is that with growing experience from dealing with MNEs, the Sudanese government has become much stricter in requiring MNEs to use local human resources. The previously relaxed terms and conditions regarding employment in FDI contracts have changed to the current explicit requirement of using at least 50% and as high as 95% local employees (Sudanese interviewee who participated in the negotiation in 1996 with CNPC, 5 May 2008). Another is that CNPC understands of the importance of meeting such demands for its long term success in Sudan as well as other countries. Finally, the consequent cost advantage will increase as CNPC’s own labour costs increase, as a result of China’s rising productivity, wage expectations and exchange rate. Table 3 presents CNPC’s employee localisation, showing an average of 73% in GNPOC, the CNPC-led

Consortium, by 2008 based on the CNPC source. Our follow-up interview in May 2010 with a Sudanese entrepreneur, who is in the position to overview the overall “Sudanization plan” designed by the Sudanese government, provided the following data: by May 2010 the Sudanization ratio (percentage of the Sudanese to the total employees) was 93% in GNPOC, 90% in PDOC, 85% in Block 6, and 84% in WNPOC 84%3. This indicates that the CNPC source matches the Sudanese source and the localisation ratio of the CNPC is similar with that of Petronas. Interestingly, we discovered that lower skilled jobs in GNPOC had lower level of localization, compared with the high skilled jobs. This result matches the finding at other Chinese firms in Sudan, which all complained that applicants for lower-level jobs were more difficult to find, due to the lack of experience and communication skills of local people, many of whom are unable to speak English.

Table 3 CNPC’s employment localization in the Sudan

Sources: CNPC, 2008; A Sudanese interviewee, May 2010.

Notes: * Data in 2008 and again in May 2010. ** Data by Feb 2008. Three styles of training have been provided in CNPC for local employees: onsite training, training in CNPC’s headquarters in Beijing and overseas investment sites, and selecting those with potential to study in China and return to work in Sudan. For example, since 1998, CNPC has spent $1.5 million to enable 35 Sudanese students to study and obtain degrees in Petroleum at the University at Beijing (CNPC, 2008, pp. 4-5).

4.3.2. Indirect impacts

The indirect impacts that CNPC’s investment has made on Sudan are best represented by its linkage effect.FDI in oil is often accused of contributing little to development due to limited linkage opportunities. Because of the high investment involved and the relatively low transportation costs of the end products, the oil majors have been reluctant to establish petrochemical plants in developing countries with some exceptions (Oman and Chesnais, 1989). It has been difficult to encourage oil MNEs to develop downstream activities where and when it is in the host country’s long-term economic interests. In this regard, CNPC’s impact on Sudan’s economy arises not only from oil exploitation, but also from petrochemical business.

As early as March 1997, CNCP and Sudanese government officially signed the general agreement on jointly investing and constructing Khartoum Refinery Co. LtD (KRC) with each party holding 50% shares. The KRC was started to operate in 2000 with refinery capacity of 2.5 million tons, which was expanded to 5 million tons by 2006. The refinery was entirely designed and constructed by the Chinese, with key equipment and facilities from Germany, France, and China. This capacity can meet demand of not only the entire Sudan, but also a small proportion of export. Petrol stations in Khartoum are run by a wide range of global companies including Shell, Petronas and CNPC, with much lower prices than the global market. According to the Agreement signed by the two sides, CNPC was required to transfer all its technology that operates the KRC to local enterprise within eight years. To meet this requirement, training for local employees was provided in Sudan and China. The Chinese Executive admitted this is a difficult task, and were concerned about the safety of the refinery after the transition, because local employees were still reluctant to be fully disciplined. The executive believes this relates to the country not having experienced industrialisation and the public lacking exposure to factory discipline. It acquired international technology to deal with wasted oil in Khartoum Refinery to meet the environmental standard set by the host country as well as the international community.

Petrochemicals are considered an important downstream business of the oil industry, and keyto provide inputs for numerous consumingindustries, leading to development of manufacturing. CNPC helped establish Khartoum

Petrochemical Ltd, alongside the refinery. At peak time the factory employed 340, of which 89 were Chinese, 35 Bangladeshi, and 216 local. One of the Sudanese employees stated that he resigned from his previous primary school teacher position to work in this factory because of the higher payment. It was revealed that he was paid $300 per month, while his Bangladeshi colleague was paid $250 per month and drivers were $800-900 per month. Although still small (52 tons/day) this factory is already able to meet the domestic demand for woven sacks. The executive revealed that the factory would soon be expanded in order to develop ethylene products, another high

demanded business in Sudan,

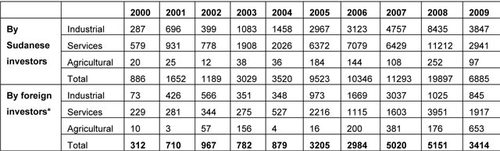

There are other linkage effects too. With the increased development of the oil and petrochemical industry in the country, domestic firms have grown and played increasing complementary roles - such as an operator of the oil consortium for Block 17 and a service company Red Corporate which provides project management services to large oil companies previously in Sudan but now in global market as well. This further stimulates the increase of equipment suppliers such as DAL Group, the top indigenous private company in Sudan. More interestingly, a wave of overseas returning has been triggered, with many highly qualified and experienced Sudanese returning to the country since 2003 to exploit their knowledge learnt overseas and explore the opportunities in the booming domestic economy. Table 4 demonstrates the rapid rise in domestic investment from 2000, especially in industrial and service sectors, indicating the linkage effect.

Table 4 Capital invested by Sudanese and foreign investors for the period 2000 – 2009 (Million US$)

Source: Ministry of Investment, the Sudan, May 2010.

Notes: * Capital invested by foreign investors includes those partnerships between foreign and domestic investors.

4.4 Sudanese government diversifies investment and the cascade effect on non-oil sectors

Previous literature claims that the resource curse could be overcome and development may be achieved if the host government is able to use the resource income wisely, e.g. establishing oil stabilization fund, and diversifying FDI to important non-oil sectors. The Sudanese government has set up a stabilisation fund, the Oil Revenues Stabilization account, which by late 2008 was among the fifty largest such funds globally. Meanwhile, during the last decade a wide range of projects has been started or completed by government re-investment of oil-revenue. Among its Government Development Programme between 2000 and 2005, investment in agriculture was increased from US$6 million to US$47 million, in infrastructure from US$2.5 million to US$17 million, in social welfare including education and health from US$1.4 million to US$7 million (Ministry of Finance, Sudan, 2008), In addition, with the new influx of foreign and domestic investment attracted by the booming economy in Sudan, the government has encouraged investors to enter non-oil sectors.

4.4.1 Oil Revenue Stabilization Account

In oil rich developing countries, the oil industry is playing an increasing role in how a country's oil and gas are extracted, where the revenues go, and how the general public will benefit. Oil funds, as used in developed countries too, are considered important for these countries to manage oil revenue towards long term development, as well as to overcome the well known ‘Dutch disease’of rising labour costs and exchange rates which choke off non-oil industrial development. One function of oil fund is to keep economy stable. Any investment spending from the fund should be counter-cyclical not pro-cyclical. In practice, developing countries like Sudan are expected to keep a large proportion of their natural-resource funds in safe foreign investments (e.g. US dollar bonds), as this preserves their

value and avoids too much absorption into the domestic economy. So even if counter-cyclical spending (to maintain growth or avoid recession) has a future return, in the sense of higher private-sector income and more tax revenue, it isn't strictly investment, and an oil fund should not be used for this purpose. The econometric estimation results from a 30-year panel data set of 15 countries with and without oil funds suggest that oil funds also deliver macroeconomic benefits, being associated with reduced volatility of broad money and prices and lower inflation (Shabsigh and Ilahi, 2007).

Sudan set up its Oil Revenue Stabilization Account in 2002, with an asset of $24.6 million in 2007, $122.4 million in 2009, and an estimated $122.4 million by April 2010 (IMF, Ministry of Finance, Sudan, quoted from Lim, 2010). There is no evidence that the Northern Sudanese government has used this account for current spending. On the one hand, there was an international scrutiny on Sudan’s oil revenue and its role in the civil conflict. On the other hand, setting up such transparent fund would be positive for the country to attract to donors (Melby, 2002). Sudan’s Oil Revenue Stabilization Account has not shown its effect on development due to the short time of its establishment, but should be encouraged as a positive contribution towards development.

4.4.2 Investment in infrastructure

By 2002, Sudan had 5,995 kilometers (km) of railroad track but more than 90 percent of the track was out of use due to civil war damage and failed maintenance. The overall road system was 11,900 km, of which 4,320 km were paved, given the nation’s size of 250 square km. Crucially, there was only one major road (below motorway standard): the Khartoum - Port Sudan road which accounted for 1,197 km and was completed in 1980 (Encyclopaedia of Nations, 2010). However, Sudan’s infrastructure construction started to speed up in 2002 due not only to the rising oil revenue, but also the availability of international investment and loans for which oil export was a precondition. Another high quality road between Khartoum and Merowe Dam, more than 2,000 km, was completed by 2008. Port Sudan, the sole port of the country, has been upgraded. Several power plants have been constructed and put in use, leading to less frequency of power cut. The project of the Merowe Dam on the Nile is a case in point. This is the largest hydropower project in Africa. The purpose of the project is electric power generation, supply of water for irrigation and flood control. As recently as 2005 about 600 MW of power were installed in Sudan for about 35 million people which was less than 20 Watts per person4.However, insufficient funding and lack of investor interest stalled the project for several decades. After 2000, a considerably improved credit worthiness brought an influx of foreign investment. The total investment will be around 4 billion Euros, of which a large proportion was funded by foreign investors (Table 5). The contracts for the construction of the Dam were signed in 2002 and 2003. The dam’s powerhouse has 1250 MW output on its completion by late 2008, doubling the current national capacity and giving the hope of not only ending the history of power cuts, but also supporting expansion of manufacturing and service businesses. Chinese company Sinohydro was contracted to construct the Dam while ABB provided power equipment. At its peak this dam construction required 5,000 employees, 2,500 were local. At the site of construction, the young Sudanese were watching and copying the Chinese workers on how to cement the dam body. Along the side of the dam were dozens of long dormitory buildings giving both Chinese and Sudanese workers accommodation, sports, entertainment, and training, as the Dam is located remotely more than 6 hours’ driving distance from Khartoum. The Dam was completed and started to generate electricity in 2009, significantly easing the country’s longstanding power shortage.

Table 5 Major investors in Merowe Dam construction project*

Source: Merowe Dam Construction Committee, the Sudan, 2010.

Note: *Funding contributors for migrations compensation due to dam construction are not listed.

4.4.3 Investment in telecommunications

Telecommunication is fundamental to the development of welfare, health and democracy as well as most types of business. "The impact that mobile phones have on the developing world is as revolutionary as roads, railways and ports” (Waverman, 2007).In Khartoum one would be surprised by the scene that there are few good quality roads but many ordinary people speaking frequently on mobile phones. Three Sudanese interviewees who work in telecommunication companies explained that this was not the case even a few years ago. In 1990 Sudan had only one fixed-line company, SudanTel, whose charges were so high that most Sudanese were unable to afford a phone. Since 1997 the Sudanese government has encouraged both domestic and foreign investment in the sector. This soon produced one of the world’s most competitive telecom markets.

By 2008 operators included Zain, Sudani, MTN, and Canar, while vendor included Huawei, ZTE, Ericsson, Siemens and Alcatel. Numerous cooperative and competitive relations were formed between these vendors and operators, which benefited local customers, as well as local operators such as Sudani. Sudani has business with both Huawei and ZTE, two top Chinese players, so as to benefit from their reducing price to compete for contracts. On one occasion competition even enabled mobile subscribers to speak for free. Poor people are able to afford mobile expenditure by dialing and cutting the connection so that those better able to pay can call them back. The poor can also take advantages of many deals such as free speech in late hours.

4.4.4 Investment in manufacturing

When building dams and other infrastructure, steel, cement and all sorts of machinery equipment and facilities are required. At the beginning most of these had to be imported, but the costs made this virtually impossible. Sinohydro had thousands of tons of cement imported from Turkey and Egypt. On one occasion, the site manager needed cement urgently but Port Sudan was slow with its customs checks. After passing the customs, they were unable to find sufficient trucks. After assembling the trucks they could not find drivers. Eventually the cement was on the way to the site but was caught by rain and could not be used any more. Such cases encouraged not only the Chinese but local entrepreneurs to invest in import substitution. For example, consumer goods are also in high demand, driven by the growing economy and increased income. Dal Group, a pure domestic family company started to enter or expanded its business to a wider range from automobile to food and soft drink. Dal was licensed as a bottler of Coca Cola - applying for permission from a Coca Cola sub company in Saudi Arabia, as it is unable to apply direct to Coke in the USA due to sanctions. In Khartoum everywhere is the advertisement of this Coca Cola brand, a striking contrast to the tense relations between Sudan and the USA.

4.4.5 Investment in agriculture

Sudan is an agricultural country. A report from the Sudanese government (Internal document, 2008) showed that by 2008 agriculture provided 40% of its GDP, 65% of its employment, and 80% of its non-oil export income. Before oil export began in 2000, agricultural export was the sole source of foreign exchange. Although rich in land and water, Sudan’s agriculture was underdeveloped due to the civil war, lack of capital, equipment, electricity, water supply (with no adequate connections to the Nile), and even suitable technology to improve productivity (Internal document, 2008). The government has realised the importance and huge potential of this sector, stressing “agriculture is Sudan’s other oil”. Aiming for a historical development, the government sets year 2009 as“Agricultural Year”, together with a grand development plan 2007-2010 to attract future investment. Local companies like Dal Group have suffered from high import price for agriculture products which are major inputs of their food and soft drink businesses. Dal has said it is extremely keen to cooperate with Chinese companies like COFCO to develop agriculture business, even a possible bio fuel business.

Chinese MNEs play an important role in the sector also by providing agriculture equipment, as seen in Dal’s storage. Moreover, original farms were set up by the Chinese when they realised that Chinese workers in Sudan demand vegetables which are not produced locally. They started to set up farms to produce these vegetables. One farm the author visited in the suburb of Khartoum was run by a Chinese woman, who came to Sudan as a doctor, but turned herself into a farmer when sensing the lack of local supply. She hired about 30 employees in her farm all locals except two farm technicians hired from a Chinese agricultural science academy. She hired local employees because of “lower cost and constraint by migration rule”, as she was allowed to hire two employees only from China. There were two other farms in Khartoum run by Chinese when she started 5 years ago, but now there were more than 10 in Khartoum.

4.4.6 Pro-poor spending and human capital focus

Combating poverty is a consistent challenge in Sudan. Given the dominant position of oil in the country, “ensuring equitable resources allocation through decentralization policies” and using oil revenue to “facilitate financing of pro-poor programs and activities”, which are important for resource-rich developing countries (Bossert, et al., 2003), are among the focuses of the government. While ways to decentralize resource allocation power are still being devised, the government does present some concrete plans for pro-poor spending, including (1) directing the banking sector to increase pro-poor funding through assigning 10% loanable funds of the commercial Banks for pro poor activities; (2) confining the financing of Saving and Development Bank to solely for pro-poor activates; (3) utilizing Zakat resources to instigate social development programs as poverty social safety nets; (4) avail employment opportunities to 20,000 higher education graduate in public administration (mainly education, health, agriculture and veterinary sectors); (5) supporting 120 thousand higher education students through the student support fund (Sudan Consortium, 2006). As a result, progress has been observed in some areas. According to the IMF’s Staff Monitored Program Note for Sudan (IMF, 21 April 2010), “Progress was made in meeting some of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), including reducing the prevalence of underweight children, increasing immunization of one-year olds, and increasing the percentage of births attended by health professionals”.

However, it is noted that spending on health and education in the pro-poor programme is still low, less than 15% of pro-poor spending over the period 2000-2006. In principle education is free and compulsory in Sudan between the ages of 6 and 13, but in 2003 only about 60% of primary school-aged children were enrolled in school and 35% of secondary school-aged children attended school. About 63% (2005 figure) of Sudanese people were literate, and significantly more men are literate than women. These data indicate that Sudan’s education is close to average for Africa and at the low end of the world scale (UNESCO, 2008), underlining the low quality of human capital in the country. This was related to the lengthy civil war and government’s historical low expenditure on education. Education expenditure as percentage of GDP declined from 5% in 1980 to 1% in 1991. The situation seemed to be improved since middle 1990s, but not significant. Education expenditure accounted for 1.9% GDP in 2003 (UNICEF, 2008).

4.5 Development indications of Chinese SOEs in Sudan

4.5.1 Development implication

Since Sudan started to export oil in 1999, significant changes have taken place in its economy. It has one of the fastest growing economies in Africa (second only to another resource-rich country now emerging from civil conflict, Angola), with an average annual growth rates in GDP of more than 9% between 2005 and 2009 (see Table 2)5. By regional and even global comparison, this represents exceptional economic growth during the last decade between 1997 and 2007. Benchmarked by certain conditions we set out earlier in the framework, we are able to provide evidence that the host government is making use of the economic growth as foundation to promote development in other dimensions, including setting up resource stabilisation fund, diversifying investment to non-resource sectors, encouraging domestic investment, installing much improved infrastructure including electricity and water supply, ending decades-long civil war with the oil revenue share agreement, and promoting free movement within south and north Sudan, which have been deeply divided as a result of European colonial intervention long before China’s arrival. It can be further demonstrated that these positive developments were achieved through the interaction between FDI and host institutions.

4.5.2 How to achieve institutional fit

Research evidence shows that the institutional fit was achieved through mutual adaptation and interchange between Chinese MNEs and local institutions. Adaptation includes learning, understanding, and fitting in with the existing institutions in order to get the things done. But as well as adapting, Chinese MNEs have worked to innovate and improve the existing institutions in order to get things done better. All the studied Chinese MNEs indicated that they firstly adapted themselves to fit the existing institution, but then actively worked on innovating and improving. At the same time, the host government made use of and sometimes manipulated Chinese MNEs’ strategy and capability to serve its development goals.

When CNPC started to invest in the country, Sudan did not have a meaningful oil industry due to a lack of discoveries in large oil reserves and sizable production. There were no complete laws, regulations, instructions and ready oil exploration data for foreign investors to follow. Politically, Sudan was severely divided into Northern and Southern regimes. CNPC dealt with the Northern government, which is the government recognised by a majority of countries. However, it had to face challenges of political instability and a frequently hostile attitude from the South, which speculated that CNPC was assisting the Northern government by producing oil and providing oil income. Socially and culturally Sudan was divided into numerous ethnic tribes, most seriously between Muslims and Christians. The Chinese company, while respecting both religions, needed to take extra care to not offend either of them. Without any industrialization experiences, skills required in oilfield and related industries were unavailable. Most local people were unaware of things such as“working discipline” and “time schedule”. CNPC was willing and able to adapt to such institutional constraints because they aimed to find and produce oil overseas. With the exception of civil war, they were also familiar with such cultural and human resource constraints from domestic operation in China.

At the same time, given the heavy investment and risk taken, CNPC (like any other MNE) needs to innovate and improve the institutional environment in order to have less risk and a better return. For instance, CNPC’s “efficiency orientated” style in conducting any project has obviously propelled the local agencies to transform their bureaucratic style (Sudanese interviewee, 24 April 2008).

The Sudanese government, on the other hand, was aware of the need to improve institutional environment in order to attract more investment. In terms of governance, Sudan has a highly centralised authoritarian regime with the current president Omar El Bashir in power since 1989. However, there is no evidence to suggest that the host government is incapable of maximising host country interests. Firstly, the Sudanese government openly invited potential bidders from all over the world to explore and develop the country’s oilfields (see below for more details) in order to search for most suitable investors from the introduced competition. It strictly followed international standards when signing contracts with foreign investors, which was demonstrated in the standardized PSA (Production Sharing Agreement) containing detailed requirements from technology standards to the minimum ratio of local employment to expatriates. All the agreements signed with the foreign companies abide them to take local companies or institutions as subcontractors for the type of work that could be done with local expertise. Secondly, almost all the oil blocks in Sudan were granted conditionally and they had to be developed under joint ventures (see below in Table 7) within which multiple partners contributed capital, technology, and/or advice. In many cases western firms were hired by the Sudanese government as project designers or supervisors. In the case of GNPOC, it was deliberately formed as a joint venture to benefit from all partners, and also followed a formal corporate governance mode through which all partners have voting power to enable them to scrutinize each other and thus maximize the interests of the host country (interviews with two Sudanese administrators working in GNPOC for five years in April 2008). Thirdly, establishing formal laws and regulations has been considered by the host government as “necessary and urgent” to benefit from FDI (official at Ministry of Energy and Mining, Sudan, interviewed in April 2008). One example was that the Ministry of Energy and Mining of Sudan published for the first time an“Investor Manual on Energy and Mining Fields” in 2006 to inform and instruct potential investors. The Investor Manual clearly stated as an objective to “Protect investors’ interests in Sudan”. Moreover, the Ministry of Energy and Mining also lists detailed information on oil blocks including size, reserves and so on for potential investors. This is a good example of ensuring transparency. Fourthly, improving efficiency and overcoming corruption have been considered necessary to attract potential investors and to keep existing investors in Sudan. All the interviewed Chinese investors in Sudan indicated that Sudanese government agencies were “slow and inefficient” but “have made huge progress” since their entry. Finally and most importantly, understanding that a peaceful environment is vital for attracting FDI, Northern and Southern governments eventually signed the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005, by allowing the South to share 40% of the oil revenue. With the improved environment, many Western oil firms have also returned to South and North.

In sum, CNPC and Sudan have achieved a close match due to the following factors: (1) long term mutual need relation. While CNPC has a mandate to search for new oil resources from non conventional markets, Sudan is able to provide China with 8% of its total need (Central Bank of Sudan, 2008). (2) While Sudan has plenty of oil, it lacked the capital and capability to turn the resource into national wealth, CNPC provided capital and capability, enabling oil exploration and a successful start of exports; (2) while Sudan was under US sanctions, and all western firms were reluctant to invest in Sudan, CNPC was willing, having taken into account not only close relation between home and host countries, but also the difficulty of accessing oil resources in the global market. This latecomer disadvantage impeded CNPC’s global strategic intent, and compels it to pursue investment in areas which longerestablished MNEs have written off as geologically or politically unworkable. (3) Concerned about developing country FDI’s inferior quality and reduced irresponsibility compared with developed country FDI, Sudan hired developed country MNEs to supervise developing country MNEs, and applies PSA and HSE international standards to achieve both quality and cost efficiency. CNPC, concerned by poor institutions harming its long term interests in the host country, and with the strategic intent to learn international management skills, is willing to work under such supervision as the PSA also sets obligations for host countries. (4) Concerned that bad governance in the developing country may reduce the benefit from FDI, the Sudanese understood the vital role of oil to the host economy, and therefore used joint venture mode to maximize their national interests while making efforts to improve transparency and services. Meanwhile, CNPC had every reason to demand good governance to ensure a higher return on its billions of dollars’ investment. To do so the company does not directly criticize the host institutions but persuades the host government to improve by demonstrating attractive prospect on FDI’s benefits to the host economy. Finally, the decade long coordination itself was a success story from adverse starting conditions, encouraging further commitment from both sides. It has encouraged FDI from other countries as well as domestic investment.

Consequently, the mutual institutional fit not only productively combined the host environment with the higher efficiency of CNPC, but also brought much improvement to the capabilities of both sides. More importantly, the good cooperation has made positive impact on the development of Sudan.

4.5.3 The unique role of Chinese MNEs in Sudan’s development

While this paper has shown that Chinese investors are contributing to Sudanese development, this still leaves open the question of whether this is the best alternative for Sudan. As noted above, China has never been the sole investor in Sudan. Before Chinese investors entered Sudan in late 1990s, western oil firms had been exploring for oil in Sudan for decades. Since Chinese oil firms’ arrival, MNEs including most of the top oil firms from developing countries have been working with the Chinese on projects such as GNPOC. As observed by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), Chinese investment in the African oil sector is growing rapidly, but it is still a small player. The accumulated investment by international companies in Africa is $170 billion, of which China has invested just $17 billion (DFID, 2008). It is therefore reasonable to assume that other investors could also contribute to promoting Sudanese development. Table 7 demonstrates that besides CNPC there are a large number of global and national oil companies investing in Sudan.

Data collected for this study on other relevant investors in Sudan enables a comparative view of the Chinese contribution. To supplement past comparisons, questions comparing CNPC with western oil firm (mainly Chevron) and other developing country oil firms (mainly Patronas and ONGC) were raised with interviewees working in the Ministry of Energy and Mining, GNPOC, local firms partnered with these firms and the general public. Data collected indicate that Chinese investors have several features which enable them to make a unique contribution to Sudan’s development.

First, the Chinese investors were more willing to take risk. Here, comparison with Chevron is especially revealing. Chevron was granted its oil concession in 1974 and discovered oil in 1978. The Shell (Sudan) Development Company Limited subsequently took a 25% interest in Chevron’s large project. Together, the companies spent about $ 1 billion in extensive seismic testing and the drilling of fifty-two wells (Talisman Energy, 1998, p. 4.). However, Chevron suspended its operation in Sudan by the end of 1984 and eventually withdrew. According to John Silcox, president of Chevron’s overseas operations, withdrawal was made because they did not want to expose their employees to “undue risk” - being in the middle of a civil war zone (Wall Street Journal, 1November, 1984). The fact that Chevron’s employees were attacked several times by the southern rebel groups6 was the proximate cause of the company’s suspension of operations, but interviewees in Sudan believed that the low global oil price and availability of better quality oil

reserves around the world in the mid 1980s also played a role in Chevron’s withdrawal. The Chinese oil company, on the other hand, took the risk of entering Sudan in 1995 when civil war had stopped but conflicts between the south and north persisted. The Chinese deployed a different approach to deal with the risk, including encouraging the peace process through sharing oil revenue between the south and the north. Most Chinese interviewees including the Commercial Consul believed that poverty is the fundamental cause of conflict in Sudan, and stimulating the

economic development will contribute to the peace process if a fair deal on oil revenue sharing can be reached by the south and north.

Second, the Chinese were willing and able to work on lower margin projects which enable the Sudanese to carry out many affordable projects. Chinese bidders for sub-contracts in oil and infrastructure sectors could offer one third lower prices than their western and even Malaysian and Indian counterparts. This was further supported by the lower cost of labour and equipment in China. For example, CNPC’s engineers in Sudan are paid less than one third of the salary while enjoying much less holidays than those at western counterparts such as Schlumberger. At the same time, although Malaysian and Indian MNEs may have as competitive a wage level as the Chinese MNEs, they do not enjoy the great advantage of cheap and reliable supplies of equipment available in China.

Third, CNPC had technology, human resources, equipment and efficiency to be able to provide a comprehensive service covering oil exploration, refining and petrochemicals, and therefore offer the foundation for sustainable development of the Sudanese oil industry. It was noted that well before the Chinese entry, the Sudanese government had a vision to “build up the integrated Sudan Petroleum Industry and make the oil industry to be the engine of Sudan’s economy”(CNPC, 2006). The integrated Sudan Petroleum Industry consisted of upstream exploration and downstream petrochemical production for export via pipeline. CNPC was able to provide all the technology and equipment needed to realise this vision. Although other MNEs in Sudan including Petronas and ONGC were able to provide the required technology and equipment, but it was questionable whether they could provide the same technology and equipment at the same price and more importantly, complete the projects within the same time constraints. CNPC achieved several world records in the oil industry in terms of speed of construction in Sudan. The company built a 15-million-ton oil field in one and a half years. It also succeeded in establishing a pipeline totaling 1,500 kilometres in 11 months and took only two years to set up the Khartoum Refinery with a processing capacity of 2.5 million tons of crude oil (expanding to 5 million tons in 2008). The Chinese and Sudanese interviewees who participated in the projects attributed such speed to China’s centralised and integrated corporate system and the resulting high efficiency, and the Chinese hardworking spirit. While western MNEs tend to spin-out non-core business and believe in the efficiency of outsourcing, many Chinese MNEs still keep an integrated structure with hundreds of thousands of employees. CNPC has 1.67 million employees across all oil-related businesses. This structure, which is often viewed by organisational analysts as disadvantageous, turns out to be effective in mobilising all the capabilities to complete comprehensive oil projects in a short time period. One Sudanese manager in GNPOC particularly compared CNPC with Petronas and ONGC which he dealt with simultaneously. He concluded that efficiency is the major difference between the three companies and further elaborated that while CNPC has unbelievably quick decision making, Petronas and ONGC worked on decisions “slowly” and inevitably “lost many opportunities”. It was also revealed that the 1,500 km pipeline project was initially contracted to a sub company of Petronas, which had to allow a CNPC unit to take over after failing to meet the deadline set by the Sudanese government.

Finally, CNPC as the largest state owned oil firm in China considered itself to have the obligation to maintain good relations with Sudan and also to protect “China’s image”. At the same time, it also enjoyed strong support from the Chinese government and state owned banks. With this feature the Chinese managers are able to use long term strategy to develop relations with the host institutions. Counterparts from the west and Petronas and ONGC are more constrained by short term considerations including profit maximization. For example, while CNPC could make a huge financial commitment to Sudan with government and bank support, Petronas and ONGC have less strong support from their respective governments and more constraints from their shareholders. Both companies are investing in several oilfields but none of them could make funding, equipment, engineer, and efficiency commitments to Sudan comparable to CNPC’s.