Africa industrization whole report 2014

Acknowledgements

The report is prepared by Prof. Dr. Li Xiaoyun, Senior Advisor of the International Poverty Reduction Center in China (IPRCC) and Dean of the College of Humanities and Development Studies, China Agricultural University with his assistants, Mr. Xu Hanze and Mr. Liu Sheng. The authors would like to thank Dr. Zuo Changsheng, Director General of the IPRCC, Ms. He Xiaojun, Deputy Director General of the IPRCC, Ms. Li Xin, Head of the Exchanges Division of the IPRCC and Ms. Xu Jin, Program Officer of the IPRCC for their support in preparing this report. The authors also give their special thanks Mr. Zhou Taidong, PhD Candidate at China Agricultural University for his translation of the report from Chinese to English.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of IPRCC and the institutions the author is affiliated with.

Contact:

Li Xiaoyun

No. 17, Qinghua Donglu, Haidian District, Beijing 100083, PRC

Tel: 0086-10-62737740/3094

Fax; 0086-10-62737725

Email: xiaoyun@cau.edu.cn

Executive summary

Within a span of some six decades, especially the three decades after reform and opening up, China has been basically transformed from a traditional agricultural country to a modern industrialized state. The share of the population employed in the secondary industry to the total population increased from 7.4 percent to 30.3 percent from 1952-2012. The share of manufactured production value to total GDP in 2013 reached 43.89%, and the production value share was 19.8% to total global manufacture production value in 2012. China’s industrialization process should not just be examined from the time frame of the past six or three decades however, China’s development is a continuation of Chinese civilization. One also needs to note that China’s industrialization not only follows a universal path, but also has its own particularities in historical, political, cultural and social conditions. Despite this great achievement, China’s industrialization process has also resulted in huge problems, including high energy consumption from extensive industrialization and environmental degradation such as worsening water quality and air pollution as well as land contamination and social inequality.

This report does not intend to describe and analyze China’s industrialization process nor make comparisons between China and Africa systematically. Instead, it summarizes and introduces some of the factors that helped China industrialize its economy and which might also be important or relevant to African (we refer to Sub-Saharan Africa) conditions. It is intended to share those experiences with African countries to help better design their industrialization policies.

China’s industrialization can be roughly divided into three stages. The first stage spans from 1953 to 1978 when China prioritized heavy industry through the centrally planned economy, with the intention of accomplishing a great leap forward and catching up with the developed world. The second stage, the period of 1979 to 1999, witnessed a more balanced development to promote light industries. The roles of the market and private businesses in promoting industrialization were emphasized and encouraged. The third stage starts from 2000 when China saw the reappearance of heavy industrialization and more knowledge intensive sectors. The process has reflected virtual interaction among the state, market and society.

China’s rapid transformation from agrarian society to an industrialized one has taken place under its unique historical, political and social economic conditions. Its development oriented nationalist political agenda from the 1950s and the 1960s helped China establish its national economy. De-developmentalized ideological and political agenda interrupted China’s industrialization from the 1960s to 1970s. After the end of the 1970s, the Chinese Communist Party (CPC) shifted its political agenda to develop the country’s economy to strength its legitimacy. Given its ruling position with a coalition of other political parties allowed by the constitution, the CPC has effectively utilized its political advantages to lead the consensus building for development through a consultative process. This has enabled various policy reforms to take place, for instance, the Rural Household Responsibility System, the township and village enterprises (TVEs) and the Special Economic Zones (SEZs).

Rapid agricultural growth spurred by these rural reforms provided surpluses, both in capital and labor for industrialization. Labor mobility and small and medium rural enterprises were immediately encouraged along with agricultural growth. Before 1984, the financial input to agriculture was more than that received from agriculture while, after 1985, the time when rural industries began to take off, more capital than received was taken out from agriculture. From 1985-1994, more than 432 billion RMB (approximately 70 billion $US) had been taken from agriculture through agricultural taxes and fees. At the same time, around 70 million rural laborers out of a total of 285 million in 1995 moved to non-agricultural jobs. China’s food crop centered agricultural growth pattern also helped to keep food prices low, thus keeping wages very low for a long time, which ultimately led China to utilize its comparative advantages to develop a labor-intensive manufacturing sector..

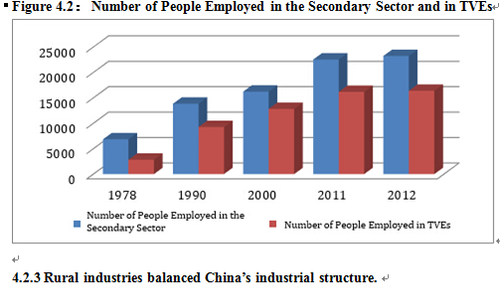

Different from previous urban based and heavy industry based strategy, China adopted the policy of promoting light and labor intensive industries in rural areas. From 1978-2006, the contribution from such rural enterprises to total industrial growth reached from 9.9% to 43.2%, and rural people employed in local state enterprises increased from 28, 27 million to 146.80 million. This industrialization path changed a distorted industrial structure from heavy capital intensive to a more balanced labor intensive structure, on the one hand, and on the other, it also avoided over-concentration of industries and population in cities. This process has been greatly promoted through steady privatization and encouraging millions of private entrepreneurs to lead local businesses.

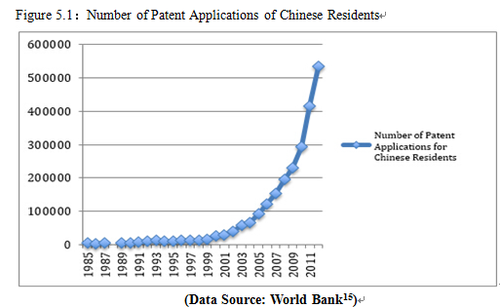

China did not just stay on low value added sectors, but has been strategically upgrading its industrial structure by encouraging technology transfer accompanied by increasing FDI . At the same time, China has developed its long run strategy to promote science and technology development through strengthening its R&D capacity and leveling up its education system to catch up to the latest technological developments.

China’s industrialization success carries many experiences, such as how to grasp the opportunities provided by globalization, how to develop infrastructure to eliminate the bottleneck for industrialization, how to develop the SEZs to absorb foreign capital and technology etc. It has also provided negative lessons, for instance environmental damage and social inequality. However, we argue that China’s industrialization does provide a reference for African countries (we refer to Sub-Saharan Africa) in their industrialization process.

Certainly Africa cannot follow China’s industrialization path, but there is a lot that Africa can learn from the Chinese industrialization experience. The essence of China’s industrialization success has been largely driven by the state-led industry policy, i.e. to use the role of the state to eliminate barriers at each stage of development so that the country’s comparative advantage can be utilized. In this regard, African countries face the challenge of how to reshape the role of the state to better use the political advantages given that most African countries’ have checks and balances based on competing politics to avoid short run, low political equilibrium. To have a consensus based development priority is essential to concentrate resources to let industrialization take place. For most African countries, to develop their agriculture is far the most important condition for industrialization because without a well-developed agricultural sector, industrialization cannot be sustainable. This does not suggest any development sequence, but rather to suggest that for agriculture-based economies, a broad-based development strategy that can link agriculture, industries as well as the services sector for labor employment and capital flow is critical. African agriculture has grown about 4-5% over the last decade, but this growth largely derives from area expansion, rather productivity improvement. Given Africa’s high population growth, Africa needs to achieve higher agricultural growth rates to produce meaningful margins. Meanwhile, global industrialization transformation will provide a great opportunity for African countries to use their comparative advantages. This can be seen from the case of increasing cost of labor in the emerging countries, particularly China. It suggests that Africa’s industrialization strategy should not only look at the conditions inside the continent, but also needs to see how their strategies can reflect how to engage with other emerging players.

Overall, to strength the role of the states and to promote agricultural development in order to lay down the foundation for taking a great opportunity to jump-start industrialization will be a challenge for African countries to move towards inclusive development.

0. Introduction

Industrialization can be defined in three ways: first, as the production of all material goods not grown directly on the land, or second, as the economic sector comprising mining, manufacturing and energy, and third as a particular way of organizing production and assumes there is a constant process of technical and social change which continually increases society’s capacity to produce a wide range of goods (Hewitt et al. 1992: p.3-6). “If you want to develop you must industrialize” (Kitching 1982: p.6) was commonplace amongst theorists and practitioners during the 1950 and 1960s. This view had been challenged on the grounds that industrialization and growth were not the same as development because they did not meet the basic needs of the population (Kiely 1998:p.7). The argument can be justified within global power structure and failed industrialization strategy that many countries adopted. China’s industrialization success suggests that industrialization participated and benefited by the population can have positive impact on development.

Within a span of some six decades, especially the three decades after reform and opening up, China has been basically transformed from a traditional agricultural country to a modern industrialized state (Liu 1997; Dong 2009). China’s industrialization process can be divided into three stages: during the first stage from 1953-1978, China adopted a planned economy and implemented an industrialization strategy that aimed to accomplish a great leap forward through prioritizing capital-intensive heavy industry (Lin 2004, p.29); in the second stage from 1979-1999, a market-oriented and balanced industrialization development strategy was implemented to address problems related to insufficient supply of consumption products and a heavily imbalanced economic structure (Ren 2010); in the third stage, from 2000 to the present, China once again entered into a new industrialization stage (Ye, 2014).

As a major driver of the overall economic growth, industrialization made great contributions to poverty reduction in China by absorbing the agricultural surplus labor force. The population employed in secondary industry increased from 15.31 million in 1952 to 232.41 million in 2012, with a net increase of 217.1 million within 60 years. The share of the population employed in the secondary industry to the total population also increased from 7.4 percent to 30.3 percent in the same period (National Bureau of Statistics, 2013). The decrease in the agricultural labor force helped to improve productivity of those who stayed in the agriculture sector and increased their income accordingly. The agricultural labor force who entered into industry also gained relatively higher income due to the difference of comparative advantages between the (two industries? and agriculture. These two aspects contributed significantly to China’s rural poverty reduction. China’s industrialization process also promoted urbanization and the development of the tertiary sector, which further employed agricultural surplus labor and promoted poverty reduction.

China has accumulated a rich experience in the process of industrialization over the past six decades, especially the recent three decades. Some scholars consider “government in the driver’s seat” as the key reason for the rapid industrialization (Shi 2011), others argue that China followed a development strategy that makes full use of its comparative advantage in the transformation process from an agricultural to an industrial economy (Lin 2004). Studies also showed that high technology and technical innovation played an important role in China’s industrial development (Jin 2003). The industrialization of China’s rural areas, especially the township and village enterprises (TVEs) was also regarded as a key factor in accelerating the industrialization process (Zhang 1999, Liu 1993). On the other hand, however, China’s industrialization process also resulted in huge problems, including high energy consumption from extensive industrialization (Byrne et al. 1996) and environmental degradation such as worsening water quality and air pollution (Ebenstein 2012; Wang et al. 2008) as well as land contamination. Some scholars have also pointed out that rural industrialization had led to agricultural land loss (GAR-ON YEH & Li 1999), and exacerbated social inequality (Rozelle 1994). Nevertheless, China’s experience of rapid industrialization still has attracted a lot of interest from the international development community and other developing countries. Prioritizing infrastructure development, attracting foreign investment, establishing special economic zones, and “crossing the river by touching the stones” have been frequently for describing China’s development features and often been referred to as an alternative development approach. For many developing countries, China has become an example of rapid industrialization and social transformation.

It is important to note that China’s industrialization process should not just be examined from the time frame of the past six or three decades. First, China’s development is a continuation of Chinese civilization. Cultural relations reflected by the unification of multiple civilizations in China developed from the long process of Chinese civil history and was closely related to the special nation building endeavor that China has undertaken in modern times. China’s development also cannot be separated from the world’s history (Fei 2000). Second, China’s development and industrialization not only follows a universal path, but also has its own particularities in historical, political, cultural and social conditions. China’s industrialization process differs from that of the Western countries and possesses its own tradition and features(Qiong & Zhihong 2005).

Africa (hereafter refers to Sub-Saharan Africa) has rich natural resources, but its industrialization process has been slow. Up until now, Africa’s exports still largely concentrate on agricultural and mineral raw materials as well as other primary products. The global share of industrial output value from Sub-Saharan Africa only accounts for about 0.7 percent or 0.5 percent, excluding that of South Africa. The contribution of manufacturing industry to gross domestic product (GDP) is less than 15 percent in most African states and even less than 5 percent in some countries[1]. From 1990 to 2002, the global share of industrial output of Sub-Saharan Africa declined from 0.79 percent to 0.74 percent, when South Africa is excluded[2]. African countries adopted several models of industrialization in different periods, including Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI), Integrated Rural Development (IRD) and Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) (Harvey 1996). None of them had led Africa’s industrialization successful.

There are many reasons for the slow growth of African industries. The first one is historical. Starting from the early 1960s when most African countries gained their independence, they were not been able to establish their own complete industrial system for lack of necessary capital and technology, despite their strenuous efforts to industrialize. After decolonization, most African countries continued to implement the previous economic policy focusing on extracting raw materials and export-oriented agricultural production. As a result, economic structures in African countries became unbalanced and most export products were resource-concentrated and had little added value. The colonial economic structure continuously affected economic and political performance of African countries and further impeded their efforts to accumulate domestic capital and seek their independent development trajectories (Mumo Nzau, 2010). Secondly, policy failures also seriously slowed down Africa’s industrialization process. African countries at independence were yearning for rapid development of their national economy to catch up with the developed world. During that period, the modernization theory, which was popular during the time and emphasized a change of deformed economic structure left over from the colonial period through import substitution industrialization, was commonly adopted by many African countries. In the two decades following, African countries established factories and the share of industry in GDP once rapidly increased. However, the optimistic growth rate did not remain longer. Factories often stopped running or ran at low capacity due to shortages of capital, limited domestic markets and lack of management capacity. As a result, many countries suffered many set-backs in this period and none of them experienced successful industrialization. By the 1980s, African countries had to accept the structural adjustment programs proposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and adopted the neo-liberal policies that followed. However, due to various reasons and lack of consideration of Africa’s specific context, including their institutional weaknesses and cultural particularities. The results were also unsatisfactory (Heidhues 2011). Social diversity, corruption, lack of labor discipline, lack of the proper capacity for planning and management, limited foreign financial flows, as well as low levels of saving and investment all contributed to the failure (Ake 2001, p.1).

Can Africa follow China’s industrialization path? The simple answer is “No”, but there is a lot that Sub-Sahara Africa can learn from the Chinese industrialization experience[3]. This report does not intend to describe and analyze China’s industrialization process or make comparisons between China and Africa. Instead, it intends to summarize and introduce some basic factors that helped China industrialize its economy and share those experiences with African countries to better design their industrialization policy. We do not consider that African countries can copy China’s industrialization model or that of any other countries. However, we do think China’s experiences and lessons can provide useful references for African countries with the opportunities Africa now has under a new global context. It is Furthermore with current political and social-economic conditions in Africa; we argue that many experiences from China’s industrialization such as the role of the state, linkages between industry and agriculture, creation of an industrialization-enabling environment and nurturing of local entrepreneurs, and infrastructure development etc are relevant to African conditions. However, we only address some of these issues that we feel basic as well as more practical to Africa conditions. This assumption carries our bias and ignorance when we tried to relate to Africa situations. The report intended to introduce the perspectives of Chinese scholars by citing more their work; however, this does not necessarily imply any rejection to the arguments of scholars from abroad.

The report consists of six parts. The first part introduces historical process, development status and existing problems regarding China’s industrialization. The second part discusses institutional aspects focusing on unique developmental politics in China. The third part introduces the role of agriculture as well private sectors in industrialization. The fourth part examines the important roles of rural industries played in China’s industrialization process. The fifth part discusses the major contributions of technical innovation and human resources. The last part discusses what lessons Africa might draw from China’s industrialization.

References

Ake C. (2001), Democracy and Development in Africa, Brookings Institution Press.

Bei, J (2003), “The Position and Role of High-tech in China's Industrial Development”, China Industrial Economy, vol. 12.

Byrne J, Shen B, Li X (1996), “The Challenge of Sustainability: Balancing China's Energy, Economic and Environmental Goals”. Energy Policy, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 455-462.

Dong, Zhi (2009), “Pathways and Achievements of New China’s Industrialization”, Research of History of the Chinese Communist Party, vol. 9, no.3.

Ebenstein A. (2012), “The Consequences of Industrialization: Evidence from Water Pollution and Digestive Cancers in China”, Review of Economics and Statistics, vo. 94, no.1, pp.186-201.

Fei, X. (2000), “Social Change in China over the Past Century and ‘Cultural Consciousness’—Speech at “Academic Workshop of International Anthropology on Human Existence and Development in the 21st Century”, Academic Journal of Xiamen University (Philosphy and Social Sciences), vol.4, p.10.

GAR-ON YEH A, Li X. (1999), “Economic Development and Agricultural Land Loss in the Pearl River Delta, China”. Habitat international, vol.23, no. 3, pp. 373-390.

Harvey C. (1996), Constraints on the Success of Structural Adjustment Programmes in Africa. Macmillan Press Ltd.,.

Heidhues, F. & Obare, G. (2011), “Lessons from Structural Adjustment Programs and Their Effects in Africa”. Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture, vo. 50, no.1.

Hewitt, T., H. Johnson & D.Wield (eds) (1992), Industrialization and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Kiely, R. (1998), Industralization and development A comparative analysis. New York: Routledge

Kitching ,G. (1982), Development and underdevelopment in historical perspective. London: Mecheun

Lin, Y. (2004), Development Strategies and Economic Development, Beijing University Press.

Lin, Y. & Liu, M. (2004), “Economic Development Strategies and China’s Industrialization”, Research on Economy, vol. 7, pp.48-58.

Liu, G., Mei, F (1993), “Township and Village Enterprises and Industrialization Road with Chinese Characteristics”, Theory Monthly, vo.2, p.3

Liu, W (1997), “Development Trends and Features of Social Transformation in Modern China”, Academic Journal of Central China Normal University, vol.1, pp. 42-48.

Mumo, N. (2010), “Africa’s Industrialization Debate: A Critical Analysis”. The Journal of Language, Technology& Entrepreneurship in Africa, vo.1, no.2.

Qiong X, Zhihong W. (2005), “Historical Choice of New Road of China's Industrialization”. Journal of Zibo University, vol. 1, no. 4.

Ren, B (2010), “Six-Decade Industrialization Evolution of New China and its Modern Transformation”, Academic Journal of Shaanxi Normal University, vol.1, pp.139-146.

Rozelle S. (1994), “Rural Industrialization and Increasing Inequality: Emerging Patterns in China′ s Reforming Economy”. Journal of Comparative Economics, vol.19, no.3. pp. 362-391.

Shi, L., Yang, D (2011), “Government-led Industrialization: ‘Chinese Model” of Economic Development”, Jiangsu Social Sciences, vol.4, pp.33-40.

Wang M, Webber M, Finlayson B, et al. (2008), “Rural Industries and Water Pollution in China”. Journal of Environmental Management, vol.86, no.4, pp. 648-659.

Ye, L., Yu, J. (2014), “Progress, New Situation and Successful Realization of China’s Industrialization”, Academic Journal of Wuhan University (Philosophy and Social Science), vol. 2, pp.117-125.

Zhang Z. (1999), “Rural industrialization in China: From Backyard Furnaces to Township and Village Enterprises”. East Asia, vol. 17, no.3, pp.61-87.

1. China’s Industrialization Process

China was completely an agrarian society before the 20th century, with 90 percent of its population living in the rural areas (King 2013). China started its industrialization process in the early 1900s. From 1912 to 1936, China’s industries increased by 8 to 9 percent annually (Chang 1969). This process was interrupted by the long-term wars in the following years. China then undertook a special industrialization path in the years following the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Different strategies were adopted at different stages since then, including prioritizing heavy industry, balancing development of heavy and light industries, and re-prioritizing heavy industry. Though China suffered from setbacks and multiple problems in this process, it basically fulfilled the transformation from an agricultural economy to an industrialization one.

1.1 Achievements of China’s Industrialization

China’s achievements in industrialization over the past six decades can be demonstrated in the following aspects. First, China has established a complete industrial system that is independent, large-scale and technology-concentrated. In 2010, China overtook the U.S. and became the world’s top manufacturing nation. In 2012, China accounted for 19.8 percent of the world’s manufacturing output. In effect, China has earned the reputation of being the “world’s factory”.

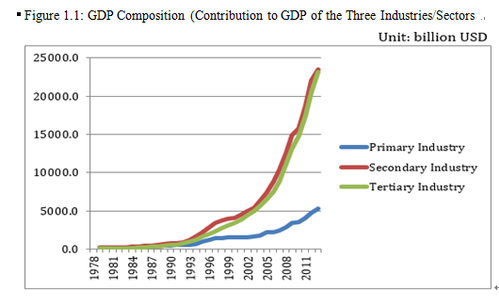

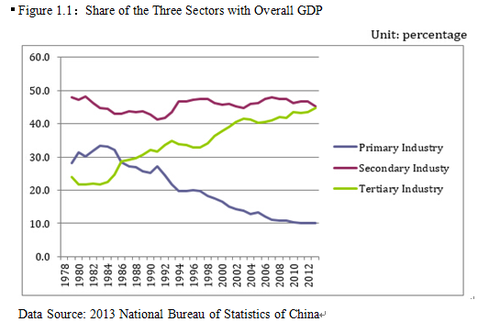

Second, sixty years of massive industrialization has brought China rapid economic growth. The Chinese economy has witnessed profound transition and growth since 1978 when China moved away from a centrally planned economy. The resulting growth has persisted for the last 35 years; China’s GDP increased from 58.7 billion U.S. dollars in 1978 to 9.17 trillion U.S. dollars in 2013, an average annual growth rate of 10 percent, making China’s economy the world’s second-largest, just after that of the United States. China’s GDP per capita also increased from less than 300 U.S. dollars before reform and opening up to 6,807 U.S. dollars in 2013 (World Bank)[4]. China’s GDP is broadly is based on three broad sectors or industries—primary industry (agriculture), secondary industry (construction and manufacturing) and tertiary industry (the service sector). As per the official 2013 data, secondary industry (manufacturing) accounted for 43.89 percent of the total GDP (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2013). Overall, the manufacturing sector has made a great contribution to China’s sustained economic growth. It has held its dominance and seen minimal change in its percentage composition in the overall GDP over the years (See Figure 2). The share of secondary industries as part of GDP in China is greater than in countries such as India, Japan, the U.S.A and Brazil[5].

Third, China’s industrialization created more employment opportunities for rural people to move out of agriculure. China’s totally employed population grew from 400 million in 1978 to 7,600 million in 2012, with an average annual increase of 1.9 percent. The employed population in secondary industry reached 2,300 million, accounting for 30.3 percent of the total employed population (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2013).

Last but not least, China’s industrialization greatly contributes to global economic growth. As China increasingly integrates into the international economy, it has driven the economic development of other countries and regions in the world, as China’s share of the world economic output increased from 1.8 percent in 1978 to 11.5 percent in 2012. China even became the largest contributor to the global economic increment in place of the U.S. after the global financial crisis, reaching more than 20 percent on average from 2008 to 2012 (National Bureau of Statistics 2013). The development of China has a strong positive overflow effect to other countries and regions.

1.2 Development Stages of China’s Industrialization

China’s industrialization can be roughly divided into three stages. The first stage spans from 1953 to 1978 when China prioritized heavy industry through the centrally planned economy, with the intention of accomplishing a great leap forward and catching up with the developed world (Lin 2004). This stage can be further divided into four periods. The first period corresponded to “the first five-year plan” (1953-1957) when China focused its efforts on the construction of 694 large and medium-sized industrial projects, including 156 supported by the Soviet Union (Wu 1999). Through these considerable efforts, China laid the primary foundations for industrialization to provide material and technological support to restore/build the national economy.

During the second period, from 1958 to 1960, China implemented a “great leap forward” industrialization strategy. The Chinese government mobilized massive amounts of investment funds and manpower to support industrial development, which emphasized heavy industry in general, and the iron and steel industry in particular. The hope was to industrialize by making use of the huge supply of cheap labor and avoid having to import heavy machinery. For various reasons, the years of the Great Leap Forward in fact saw economic decline and material shortages.

These policy failures promoted the government to re-think and adjust its policies from 1961 to 1965. During this period, China began to adopt a development strategy of coordinated and balanced development of agriculture, light industry and heavy industry. The imbalanced economic structure that resulted from the great leap forward was gradually improved and China’s economic output greatly increased.

During the fourth period or the “Cultural Revolution” from 1966 to 1978, China had implemented a strategy of “three-front” construction. The country was divided into three fronts, roughly corresponding to the three regions: costal, central and western. As most new industrial projects were located in the third-front areas, the industrial build-up in these areas has been known as the third front program. Thought it centered on heavy industry, the entire third-front build-up was dictated by considerations of military strategy rather than economic efficiency. About 95 percent of China’s basics construction investment funds were allocated to construction of defense-oriented industries. The share of heavy industry increased from 51 percent to 55.8 percent within this period. However, this policy resulted in further differences between light and heavy industry in the total economic structure and regional imbalances in industrial distribution and production.

The second stage, the period of 1979 to 1999, witnessed a more balanced development of China’s industries. In 1979, China adopted the opening up policy and started to adjust the strategy of prioritizing industrial development. The roles of the market and private businesses in promoting industrialization were emphasized and encouraged. China also paid special attention to balanced and coordinated development of different industries, with more focus on light industry. Great efforts were made in attracting foreign investment and importing advanced technologies and management experiences to tap the potential of late-starting and comparative advantages. Foreign direct investment (FDI) in China increased from about 19.6 billion U.S. dollars in 1991 to 52 billion U.S. dollars in 1999.

The third stage starts from 2000 when China saw the reappearance of heavy industrialization. The Chinese economy has moved back into a development phase of industrialization through heavy industry (Ye & Yu 2014). Many local governments have pooled physical and financial resources for the launch of large-scale projects in an attempt to drive economic growth. From 2000 to 2012, heavy industry in China grew much faster than light industry. The proportion of heavy industry increased from 53.8 percent in 1999 to 71.8 percent in 2012, while that of the light industry fell to 30 percent. The contribution rate of heavy industry to total industrial profits reached more than 72 percent in 2012. It can be seen that industrial growth during this phase largely relied on heavy industrialization.

1.3 Negative Impacts of China’s Industrialization on Resources and Environment

China currently is still in the middle stage of industrialization. Though China has sustained rapid economic growth through industrialization, it is important to note that the process has also brought a series of negative impacts, especially on resource consumption and ecological environment.

China’s high speed economic growth is at the cost of the huge consumption of fossil energy and the resulting untold damage to the environment, known as “high energy consumption, high pollution and low production”. The energy efficiency ratio in China is about 30-40 percent lower than in developed countries, while the ratio of recycling use of water resources is 50 percent lower. Energy consumption per capita GDP was about twice of the average global rate, or more than four times than in developed countries such as the U.SA and Japan. Such enormous energy consumption not only exhausted scarce natural resources, but has also brought serious environmental problems.

China’s environmental degradation has been getting worse, resulting in huge economic losses and posing serious environmental or eco-health risks. According to the 2011 Annual Report on Environment Statistics issued by China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection, industrial emissions of sulphur dioxide (SO2) accounted for 91 percent of the total emissions of SO2 in China. The persistent smog since 2012 across different regions in China is also a result of rapid industrialization (Du et al. 2014). According to World Bank statistics, annual losses caused by environment pollution were equal to 6 to 8 percent of China’s GDP. Estimates from Chinese official sources also concluded that losses, including property and health, caused by environment pollution ranged from 378.7 billion to 454.5 billion U.S. dollars in 2011, about 5-6 percent of the GDP that year. Environmental pollution has also posed huge health risks, including cancer, respiratory diseases, and cardiovascular diseases.

The African economy has been developing rapidly over recent years, with an annual increase rate of about 5 percent after 2000 and exceeding that of many other developing countries. In 2012, the GDP growth rate of Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa) reached 5.8 percent. Economic growth in the region continues to rise from 4.7 percent in 2013 to a forecasted 5.2 percent in 2014[6]. However, Africa’s economic output was just more than 2 trillion USD dollars in 2012 and the economic growth rate has largely relied on the extractive sector and the service sector. Though Africa has been making hard efforts to develop industries, it has not been able to establish its own complete industrial system. This is thought to be due to many reasons. In 2012, the global share of the industrial output from Sub-Saharan Africa was 0.7 percent or 0.5 percent if South Africa is excluded[7].

The industrial sector contributed less than 10 percent to Africa’s GDP and employs even fewer than that percentage.

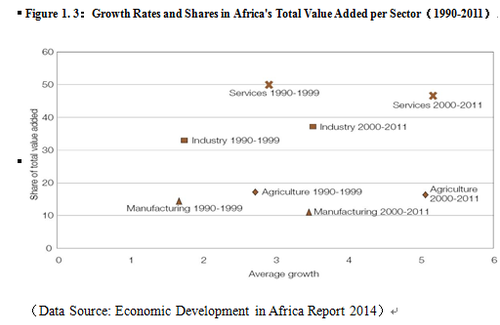

Figure 3 below shows that the share of manufacturing in total value added has declined over the past two decades, showing an average fall from 14 percent in 1990-1999 to 11 percent in 2000-2011. Furthermore, the services sector is now dominant in African economies. Its share of total value added in 2000-2011 was about 47 percent, compared to 37 percent for industry and 16 percent for agriculture. In terms of dynamics, over the same period the services sector had an average growth rate of 5.2 percent while the agriculture sector had 5.1 percent and industry, 3.5 percent. This pattern of structural change in Africa is unexpected given that the continent remains at an early stage of development. It is unusual for the services sector to play such a dominant role in an economy in the early stages of its development[8].

Various industrialization strategies have been pursued to achieve economic development in Africa. Ever since independence in the 1960s and 1970s, most African countries relied on exports of mainly primary commodities and natural resources. Most governments then embarked on a path to rapid industrialization and pursed a strategy referred as “catch-up industrialization” for import substitution. The strategy eventually failed as it over-emphasized state-owned industry and capital-intensive enterprises and ignored the development of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). During the 1980s and 1990s, African countries began to implement the structure adjustment programs (SAPs) to restore internal and external macroeconomic stability, which instead resulted in huge external debts and “de-industrialization”. For example, the Economic commission for Africa reports that from 1980 to 2009 “the share of manufacturing value in Sub-Saharan Africa fell from 16.6 percent to 12.7 percent” From the 1990s onwards, globalization and export-oriented industrialization became the new paradigm for Africa’s economic development, where countries opened up to free trade. Nevertheless, there has been little progress in Africa’s level of industrialization (NKongolo 2008).

Gĩthĩnji and Adesida (2011) pointed out there were four cores but interrelated issues at the root of the failure of the states in Africa to industrialize? The first one is a crisis of confidence. African countries may have lost confidence in development after long-term colonial rule and state failures, and most African countries seem content exporting their primary products. The second reason is “the inherited colonial state” that most African countries did very little to dismantle, but used the control apparatus of this state to ensure continued domination control of the country. The third one lies in “the outsourcing of development. Africa relies on exports and foreign aid and does not have their own development initiatives. The fourth one is taking “aid as development”. A key element of Africa’s problem is that aid has become a substitute for real development, which is detrimental and deprives African countries of their initiative and ownership of the process of economic transformation. Aid was initiated not for development, but for ideological purposes during the Cold War and often distorts polices and encourages unsustainable development. Many governments are developing and implementing programs not because they fit within an overarching national vision and agenda but because it is a way to obtain resources from donors.

The industrial development of a country usually starts from the production and export of primary products, moves to the production and export of technology-based capital and intermediate goods, before finally producing high-tech products. Although this does not mean that Africa will have to follow this path, it will need to develop the labor-intensive manufacturing industry given its challenges of joblessness and low economic output. Or, as declared by the African Development Bank in 2013, industrialization is a precondition for Africa’s economic transformation.

There are in fact unprecedented opportunities for Africa to embrace industrialization and solve its persistent and pervasive problem of joblessness and economic development. Labor costs in Asia, especially in China have become more and more expensive. Africa has a 1.2 billion population and has a relatively high population growth rate ( 4.8 percent in 2013)[9]. About 85 percent of its population was younger than 45 years in 2012[10]. The agriculture share of GDP is just 12 percent, according to OECD estimates, while it employs over 60 percent of the working age people[11]. What this shows is that if agricultural production efficiency is to be improved, there is a great supply of labor for Africa’s industrialization.

References

Chang, JK (1969), Industrial Development in pre-Communist China: A Quantitative Analysis, Aldine Publication Company, .Chicago.

Du, W., Zhu, S. and Zhang, P. (2014), “Impacts of China’s Industrialization and Urbanization on Environment and Solutions” (in Chinese), Studies of Financial and Economic Issues, no.5, pp. 22-29.

Gĩthĩnji, M. W and Adesida, O (2011), “Industrialization, Exports and the Developmental State in Africa :The Case for Transformation”, Working paper 2011-18, available at https://www.umass.edu/economics/publications/2011-18.pdf

King, F. H. (2013), Farmers of Forty Centuries: Organic Farming in China, Korea and Japan, Dover Publications.

Lin, Y. (2004), Development Strategies and Economic Development (in Chinese), Beijing University Press, Beijing.

Nkongolo, E.J.D. (2008), “SMEs/SMIs centered industrialization for inclusive and sustainable growth in Africa”, www.grips.ac.jp/forum/af-growth/seminar(Jul.08)/elumba(summary).pdf

Wu. L. (1999), Economic History of the People’s Republic of China (in Chinese), China Economic Press, Beijing.

Ye, L. and Yu, J. (2014), “Progress, New Situation and Successful Realization of China’s Industrialization” (in Chinese), Academic Journal of Wuhan University, no.2, pp.117-125.

2. Developmental Institutions: The Political Base of China’s Industrialization

Three main explanations were proposed to examine China’s rapid industrialization process, the strong role of the State (Li 1999), market-oriented reform and the important roles of private enterprises (Garnaut 2012; Ren 2004), as well as marketization of Chinese enterprises led by the state (Huang 2000). Although China’s industrialization, especially since the reform and opening up, has been stimulated by both strong state roles and market-oriented reform, it can be argued that the industry policy derived from its developmental politics has played a decisive role in China’s industrialization.

Either for British industrialization, US industrialization or later capitalist industrializations like Japan, the state played a vital role in industrialization. Historical study on British industrialization by Frederick List suggested that manufacturing must be developed as part of the process of nation-building (cf. Kiely 1998: p.31). Contrary to popular myth, Britain had a strong state in the sense of a public administration that effectively extracted financial resources from society (Kiely 1998: p.26). The early stage of US industrialization also confirmed the role of the states as the first Secretary of the Treasury; Alexander Hamilton made a case for government assistance to manufacturing (cf. Kiely 1998: p.32). The theory of the developmental state to some extent provides explanations of the East Asian miracle. According to Chalmers Johnson, the developmental state is “shorthand for the seamless web of political, bureaucratic, and business influences that structures economic life in capitalist Northeast Asia” (Johnson 1982). In his book MITI and the Japanese Miracle, Johnson used this term when analyzing the process of the industrialization of Japan. The theory was then widely applied to explain the East Asian development model, including China. Empirically speaking, the Chinese way of development shares many characteristics with the Asian developmental state model, including state control over finance, a dual system of public and non-public ownership, high dependence on the export market and a high rate of domestic savings (Baek 2005). However, we do not fully agree that China’s industrialization followed the developmental state model, because China is different from those case countries leading to the theory characterized by an authoritarian government accompanied by a market economy. Instead, we use “developmentization” to explain how China promoted industrialization through de-politicized and “developmentized” state apparatus. We argue that the success of China’s industrialization and economic growth comes from a combination of several factors, including developmental politics, a process of consensus building through state planning, development campaigns among local governments and gradual reforms.

2.1 Developmental Politics

China’s political system to a large extent reduces political risks derived from reform mistakes by the ruling party. Multi-party cooperation and political consultation under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CPC) is a basic political system in China. The system means that the CPC is the central force in coordination of multi-party participation in the discussion and management of state affairs. China’s political system is consensual rather than competitive. Under the leadership of the CPC, the system can build consensus even when there are many different opinions. This allows opinions to be expressed, although within political tolerance on the one hand, but mostly ensures consensus. This system also helps any reform to take place without worrying about losing power for the ruling party due to any mistake, although the party’s legitimacy still remains constantly challenged.

Legitimacy is the primary condition for any ruling party to effectively manage the state apparatus and deal with state affairs. To maintain its legitimacy, a ruling party has to adapt to changes and reconstruct its legitimacy sources (Sang 2012). The CPC experienced two major changes of its political agendas in order to seek and maintain its legitimacy sources. The first change happened in 1978 when the party’s political agenda shifted from ideology and moral incentives to economic performance and material enticements. The second change occurred in the 1990s when the legitimacy base was oriented towards economic growth, stability and nationalism (Liu 2012).

After the serious economic crisis due to the leftwing Cultural Revolution, to maintain its legitimacy, CPC decided to de-politicize itself by placing development at the core of its agenda in order to maintain its political goals. This was far the most important factor given the party’s dominant ruling role in China’s political life. For example, the “three representatives” idea emphasized that the party not only represents the interests of workers, but those of the whole people. The “three representatives” and later the “human-centered development” proposed under President Hu Jintao’s era demonstrated that the CPC went beyond its traditional class-struggle thinking and was capable of making necessary adaptations to the constantly changing political and economic environment (Wang & Xu 2006). The follow-up “scientific outlook on development” further put development in a scientific mode as one of the parties’s guiding principles. All these show that the CPC tried to developmentize the party’s agenda, making modernization the goal of the party’s policies. The CPC improved its ruling legitimacy through strategically combining the party’s agenda with public interest which was framed into “development”.

The second relied in the promotion and training of party cadres and a unified ideology among party officials at different levels. The cadre training system not only successfully helped the CPC shift from a revolutionary party to a ruling party, but also ensured a sound implementation of national development strategies in a top-down manner. According to the CPC’s Constitution, the CPC is “the vanguard both of the Chinese working class and of the Chinese people and the Chinese nation”. In fact, CPC is an elite organization with more than 85 million members and many of them are top talents from all walks of life. To improve and maintain the administrative quality and capacity of these elite party members, especially their follow-up with the party’s agenda, the CPC developed a systematic cadre training system to conduct political and cultural education as well as managerial skills. In the 1980s, the number of party schools and training centers reached 8,800 in China, the highest in history. In the 1990s, there were about 3000 party schools and administration academies across the country, employing more than 80,000 people. China established the National School of Administration in 1994 and after 2002; China established three executive leadership academies in Pudong, Jinggangshan and Yan’an and inaugurated a National School for Senior Managers in Dalian to educate the CPC officials and leaders of major state-owned enterprises. Currently, there are about 5,000 party schools, administration schools and cadre training institutes in the country (Yu 2014). Various training programs not only acquaint officials at various levels with the guidelines and blueprints of the Party and Party theories, but also improve their administrative capacities and understanding of national development strategies. In addition, the CPC has a strictly hierarchal system which extends from the central to the village level. This system can help ensure consistency between policy making and implementation at various levels (Li 2010). As Wu (2007) argued, training of party members and government officials at various levels was one of the most important reasons for the country’s success in implementing industrialization and other economic policies.

2.2. The Formulation of “Five-year Plans”: A Process of Consensus Building

China’s economic reform was not simply about introducing the market economy to replace the planning system. Instead, China employed an economic model of socialist market economy, characterized by the dominance of the state-owned sector and an open-market economy. Though the market was incorporated into the economy system to play a basic role in allocating resources, planning was still an important instrument of economic development. In fact, it has been argued that the high growth rates of the Chinese economy were maintained partly due to the Five-Year Plans (Hu 2012). China has promulgated five-year plans since 1953, which became a comprehensive and guiding road map for national economic and social development and a strategic blueprint for modernization with Chinese characteristics. Five-Year Plans usually outlined major construction projects, sectoral distribution and the government’s strategic policy priorities over a multi-year time horizon and set targets and directions for national economic development. China has altogether formulated 10 “Five-Year Plans (Ji-hua)” and two ‘Five-Year Projections (Gui-hua)”[12]. The 12th Five-Year Plan is currently under implementation.

“Five-Year Plan” in China is not just a policy document that is formulated in a closed-door manner. In fact, there are continuous interactions and consultations between the central government, local governments and other stakeholders in different planning stages such as drafting, piloting, evaluation and adjustment. The planning mechanism facilitates the formation of a huge network among policy makers from different sectors and at various levels. This process produces countless documents, guides or interventions for economic activities that shapes and constrains the behaviors of governments at different levels. Planning is enabled through the hierarchical administration system, but its efficiency depends on the performance review of party cadres. This feature defines China’s difference from other East Asian developmental states and goes beyond Western mainstream analytical frameworks (Heilmann & Melton 2013).

The formulation of China’s Five-Year Plan is based on systematic research conducted by various think tanks, including those affiliated with the party system, the State Council and its various ministries as well as research institutes and universities. This ensures that perspectives at both macro- and micro-level are fully taken into consideration. Take the “12th Five-Year Plan” as an example. Its formulation was a long-term and complicated process with the participation of many stakeholders. It included at least nine key steps. The first step was to review the progress of the “11th Five-Year Plan”, including a mid-term evaluation jointly conducted by the Center for China Studies at Tsinghua University, the State Council Development Research Center and the World Bank Beijing Office entrusted by the National Development and Reform Committee (NDRC) in the second half of 2008. The second step, initiated at the end of 2008, when NDRC selected more than 20 issues related to social and economic development and people’s major concerns such as policies on attracting foreign investment and the reform of the income distribution system, and then organized consultation meetings with experts, scholars and entrepreneurs. Thousands of political and economic experts were involved for an entire year to explore strategies to develop China’s economy and society. The third step was to determine basic guidelines by the national leadership based on the research and consultation results. A consultative draft for the plan was then formulated to provide basis for a special expert committee to deliberate and comment for further revisions. The fifth step was a discussion of the revised consultative draft at the Fifth Plenary Session of the 17th Central Committee of the CPC in October 2010. More opinions and advice were collected during the meeting. After that, the final plan was drafted in early 2011 (the sixth step). The seventh step involved discussions on details of the draft in January 2011 by the special expert committee, followed by the eighth step of a public opinion collection/assessment process) conducted by the Prime Minister during January to February of 2011. The ninth or the final step was to submit the draft plan to the National People’s Congress (NPC) for deliberation and discussion. After the draft was approved by the NPC, the State Council promulgated and then implemented the plan. The formulation of the “12th Five-Year Plan” was thus a process of building consensus about China’s future through coordinating different interests, visions and opinions (Hu 2011).

In addition, the State Council also develops special plans and regional plans, which together with the “Five-Year Plans” (also known as overall plans) serve as the guidelines for provincial, municipal and county governments in making their own development plans. This planning system, known as “three levels and three types” (the three levels include national, provincial and city/county; and the three types include overall, special and regional), is in fact a huge network that connects policy makers from the central government and the many local governments. Under the development framework decided by the central government and in coordination with national and upper-level development policies, local governments at various levels can determine their own development priorities and objectives in their own jurisdictions (Cheng 2004). Therefore, it can be seen that the planning system was in fact a process of building consensus, and development plans were formulated and put into practice only when there had been wide discussions and deliberations.

2.3 Development Competitions at Local Levels

In addition to developmentized politics and state planning, local governments and the competitions in development among them are also important driving forces of China’s economic growth. For example, Zhang (2007) has argued that competition among local governments had a decisive impact on China’s economic growth. The activeness of local governments in pushing forward local economic development was largely the result of two factors: administrative and fiscal decentralization and the country’s performance appraisal and management system.

Starting from the 1980s, the central government began to implement administrative and fiscal decentralization. Local governments began to assume primary responsibilities for economic development in their jurisdictions and enjoyed a wide range of authority devolved from the central government. Local governments have thus gradually become economic agents with independent interests and economic policymaking rights. They promoted economic development through building infrastructures and attracting investment. For example, in each location, special project offices were set up to attract external investments and funds.

At the same time, China also introduced de facto fiscal federalism through the “fiscal contracting system”. This was based on the principle of “dividing revenue and expenditure with each level of government responsible for balancing its own budget”, which is mainly characterized by a system including central taxes, local taxes, and central-local sharing of taxes. Central taxes would go into the central coffer, and local taxes into local budgets. As for shared taxes, they were to be divided between the central and provincial governments according to some established formulas. Fiscal decentralization has actually caused tax revenues to shift from the central government to local governments and put more incentives on economic performance as local governments could have more savings when they had higher financial revenues.

The second interrelated factor was the country’s performance appraisal and management system. While administrative and fiscal decentralization granted local governments more power and incentives in developing their local economies, it was further strengthened by the country’s performance system which put more weight on economic growth indicators in reviewing the performance of local governments. The GDP growth rate was closely connected with the promotion of local government officials. Programs like selection of “the strongest 100 counties” were also put in place to set examples and encourage competition among local governments. This definitely shaped the development orientations of local governments. In the past three decades, local governments acted like regional companies. Despite continuous promotion and changes of “company mangers” (local leaders), GDP and revenues maintained a high growth rate. This was characterized by some Chinese scholars as a “promotion-tournament governance model” and was regarded as a major driver of China’s economic miracle (Zhou 2007).

It is important to note that development competitions among local governments resulting from decentralization did not lead to complete localism. The central government could still exert influence on local government behaviors through the appointment and dismissal of government officials, the formulation and implementation of national Five-Year Plans, and using national laws and regulations to remove regional barriers.

2.4 Gradual Reforms

China has taken a steady and gradual approach to the implementation of economic reforms rather than using the “shock therapy” tactics of the former Soviet Union countries. China’s reform was conducted in a “bottom-up” manner and followed an “easy-to hard sequence”. From 1978 to the 1990s, China’s many reform initiatives came from farmers and workers in rural and urban areas, which were adopted in their localities and then by the central government to diffuse throughout the country when there were successful results. The Chinese government also piloted many of its reform initiatives in certain locations first before spreading them to other places. Gradual economic reforms and “proceeding from point to surface” (models tested regionally and then adopted nationally if successful), though unable to achieve large-scale effects in a short time, ensured that losses from economic reforms were immediate and enabled correction and the successful implementation without major disruption (Ma 2008).

Take the opening-up policy for example. China first established special economic zones in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou and Xiamen in the early 1980s, which was then extended to 14 other coastal cities in the middle 1980s. China then set the Pearl River Delta, Yangtze River Delta, Jiaodong Peninsula and Liaodong Peninsula as open economic zones. In the early 1990s, China made the policy of opening up Pudong district in Shanghai. Following that, opening up zones were further extended to inland and border cities. China now has a development landscape composed of “special economic zones, open coastal cities, coastal economic zones and inland cities”.

The opening up process does not stop at the cities. Local governments also set up economic development zones in accordance with national policies. Starting from 2008, the State Council started to formulate benchmarks and upgrade provincial economic development zones. By 2011, there are 131 national economic and technical development zones, among which 66 are located in the eastern areas, 38 in the middle and 27 in the western. The number of national economic and technical development zones reached 215 in 2014. Widely distributed across the country, these zones have become important poles for economic and social development. In addition, municipal and county governments also established industrial development parks, where transportation, electricity and water infrastructures are installed and taxes are preferential, to attract external funds or large enterprises to invest there. Therefore, it can be seen that China’s opening-up process was conducted in a gradualist manner, proceeding from big cities to small and medium cities, and from the eastern and middle part to the western areas of China..

The central government also allows and encourages local governments to take different initiatives to develop their own economies based on their local contexts. Different development models have emerged along the years, including: the “Wenzhou Model” that features household industries and specialized markets; the “Sunan Model” that uses local farmers and talents to develop township and village enterprises; the “Quanzhou Model” that has strong private enterprises and an industrial concentration of light industry; and the “Pearl River Model” where the rapid industrialization is export-oriented and led by local government through utilizing its geographic advantages. These different initiatives showed that there was no one single model that can fully describe or explain China’s industrialization and economic development. Instead, China’s development relies on multiple ways that take into consideration the local contexts and comparative advantages.

China’s gradual economic transition accumulated rich reform experiences. However, we consider that at the core of the success is the development model of “market economy plus socialism”. Here we can consider three aspects. The first is to gradually introduce ‘the market’ into the original planned economy and improve market economies in the process of economic growth. The market is used to allocate resources and to create incentives for competition. Secondly, socialism is maintained and developed in the process. Socialist principles are used to constrain and resist free-market fundamentalism and the negative impacts of liberal competition and laissez-faire economy. As demonstrated above, the Chinese government has continuously improved its capacity to regulate markets and assure social justice and common prosperity through its cadre training system. The third point is to combine the market economy with socialism in an organic way and to tap their respective advantages. While the market is used to promote liberal competition among individuals and other market entities, the government plays the role of concentrating resources to accomplish major projects (Li and Zhang 2008).

As most African countries still have an underdeveloped market and private entrepreneurship, the role of the government becomes extremely important in promoting industrialization. However, as Gĩthĩnji and Adesida (2011) point out, Africa’s political system is inherited from the colonial state after independence, which was created for colonial rule rather than Africa’s own development. Though many African countries followed the experience of a socialist planned economy in the immediate period after independence, the Western model gained dominance again after the onset of structural adjustment programs (SAPS) and the neo-liberal ideology on the continent. Currently, the political system in Africa is akin to Western representative democracy based on different interest groups, but with Africa’s own political traditions included. In the context of multi-party elections where political parties are not necessarily ideological vehicles, but more likely simple instruments to achieve power, the political system becomes problematic as changes in regime may mean a desire to pick a different set of winners and losers among the representatives and more aligned with the new regime. Therefore, though most African countries have their own development planning, they differ greatly from China because the governments and the civil societies often do not share common agendas or initiatives. Discussions on development priorities can easily fall prey to conflicts among different parties rather than forming consensus. For industrialization to occur, political elites in African countries will need to agree on a long term commitment to creating industry regardless of who is in power.

References

Baek, S. W. (2005), “Does China follow ‘the East Asian Development Model’”, Journal of Contemporary Asia, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 485-498.

Brautigam, D. (2009), The Dragon's Gift:The Real Story of China in Africa, Oxford University Press.

Cheng, S. (2004), “On Development Planning under the Chinese Socialism Market Economy” (in Chinese), Academic Journal of Public Administration, vol.1, no.2, pp.4-12.

Garnaut R., Song, L., Yao, Y. and Wang, X. (2012), Private Enterprise in China, ANU E Press, Canberra.

Gĩthĩnji, M. W and Adesida, O (2011), “Industrialization, Exports and the Developmental State in Africa :The Case for Transformation”, Working paper 2011-18, available at https://www.umass.edu/economics/publications/2011-18.pdf

Heilmann, S. and Melton, O. (2013), “The Reinvention of Development Planning in China, 1993-2012”, Modern China, vol. 39, no. 6.

Hu, A. (2011), “Democratic Process of Planning”, China Daily, available at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2011-03/10/content_12146877.htm

Hu, A. (2013), “China’s Special Five-Year Plan Transition” (in Chinese), Journal of Opening-up Times, vol. 6, p.4.

Huang, S. (2000), “Three Hypothesis on Institutional Change and Their Testing” (in Chinese), Journal of Chinese Social Sciences, vol.4, pp.37-49.

Johnson, C. (1982), MITI and the Japanese Miracle; The Growth of Industrial Policy 1925-1975, Stanford University Press.

Leftwich, A. (1995), "Bringing Politics back in: Towards a Model of the Developmental State", Journal of Development Studies, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 400-427.

Li, W. (1999), “The Forming and Shifting of the East Asian Government-led Development Model” (in Chinese), Journal of Contemporary Asia Pacific, vol. 7, pp.32-37.

Li, X. (2010), Development and Poverty Reduction in China and Africa: a Comparison of Multiple Perspectives (in Chinese), China Fiscal and Economic Press, Beijing.

Li. W, and Zhang, Z. (2008), “An Exploration of Experiences of China’s Gradual Transition and Its Development Path”(in Chinese), Research of History of the Communist Party of China, no.3, p.4.

Liu, G. (2012), “Views of Foreign Scholars on Construction of the Communist Party of China” (in Chinese), Study Times, Beijing.

Ma. X. (2008), “Gradual Reforms over Three Decades: Experience and Future”, China Reform, no. 9, pp.12-15.

Ren, B. and Hong, Y. (2004), “New-type Industrialization Road: Transition of China’s Industrialization Path in the 21st Century” (in Chinese), Humanitarian Magazine, vol.1, pp.60-66.

Sang, L. (2012), “Thoughts on Reconstructing Legitimacy of the Communist Party of China during Transition” (in Chinese), Academic Journal of Hubei Provincial School of Administration, vo.1, p.6.

Wang, H. and Xu, Y. (2006), “De-politicized Politics and the Publicness of Mass Media—Interviews with Professor Wang Hui” (in Chinese), Journal of Gansu Social Sciences, vol.4, pp.235-248.

Wu, J. (2007), “Cadre Training Comes into Focus”, China Daily, October 17, 2007, available at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2007-10/17/content_6182443.htm

Yao, Y. (2009), “Neutral Government: An Explanation of China’s Economic Success during Transition” (in Chinese), Economic Comments, no. 3, pp.5-13.

Yu, K. (2014), “Cadre Education of the Communist Party of China and National Governance” (in Chinese), Academic Journal of Zhejiang Provincial Party School, no.3, pp.5-11.

Zhang, J. (2007), “Decentralization and Growth: China’s Story” (in Chinese), Economics (Quarterly), no. 1.

3. Agricultural Development: Economic base of China’s Industrialization

Agriculture is commonly the main source of resources that can be captured for industrial development. Classical industrialization theory regards agriculture as having many irreplaceable roles in industrial development, including delivering food for domestic consumption; providing labor to meet industrial demands; expanding markets for industrial products; increasing supply of domestic savings; and earning foreign exchanges (Bruce & John 1961). These five roles are also referred as product contribution, factor contribution, market contribution (Kuznets 1964), and foreign exchange contribution. Within a span of some six decades, China has basically transformed from a traditional agricultural country to a modern industrial state. China’s industrial development, both before and after the reform and opening up, was largely built on the base of agriculture.

3.1 From 1949 to 1978: agricultural accumulation to support the development of heavy industry.

From 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was founded, to 1978 before the implementation of the reform and opening up policy, China adopted a strategy of prioritizing the development of heavy industry in order rapidly to establish an industrial base. Back then China was a poor and backward agricultural country, and did not have surplus capital or access to large amounts of foreign investments for industrialization. In order to become an industrial nation, China had little choice but to rely on agricultural surpluses to initiate the industrialization. To ensure that the primitive accumulation of agricultural wealth could enter into the industrial sector, China used a “command economy” strategy to directly allocate resources. Under the overall guideline of “taking agriculture as the foundation and industry as the dominant sector of the national economy”, China introduced agriculture collectivization and the system of state monopoly on the purchase and marketing of agricultural products. While the latter was used to control most of the surplus agricultural products at a low price and to accumulate sufficient capital for industrialization through the “price scissors” in the exchange of industrial products for agricultural products, the former was implemented to provide an important institutional safeguard for the latter’s implementation. According to estimates, in the first several years of the founding of the Republic, agricultural taxes accounted for about 40 percent of national revenues (Li & Qi 2010). During the 25 years of planned economy from 1953 to 1978, “the price scissors” in the exchange of industrial products for agricultural products totaled 600 to 800 billion RMB (when China’s industrial fixed assets were only about 900 billion RMB in 1978). These institutional arrangements also helped increase China’s gross industrial capital formation with an annual average rate of 10.4 percent from 1952 to 1978. By 1978, secondary industry accounted for 48 percent of China’s GDP (Nordon 2011). However, this changed the country’s economy but did not transform the country.

3.2 The reform and opening up era: agriculture promoted labor intensive light industry.

3.2.1 Agriculture provided sufficient and high-quality labor force to the development of China’s light industry.

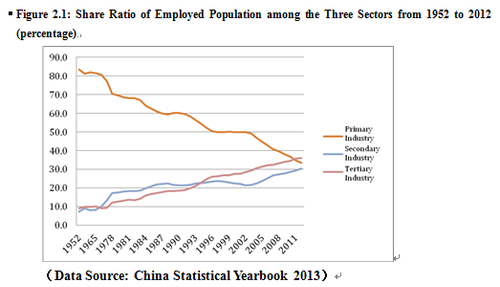

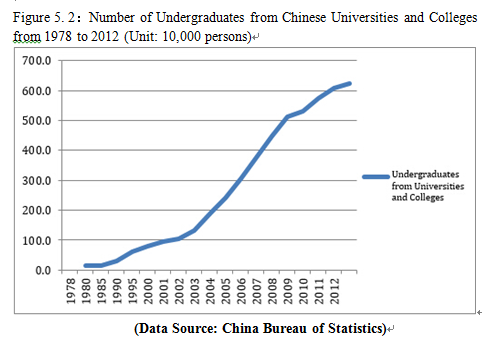

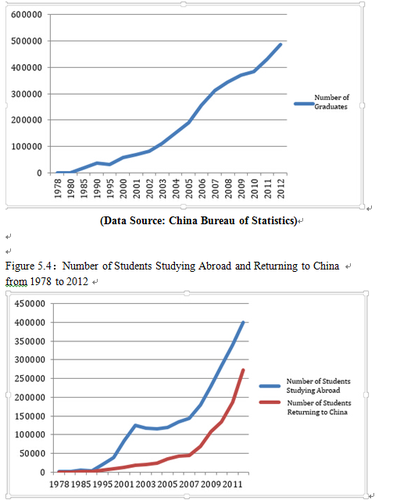

After 1978, China shifted from the previous focus on heavy industry to the development of light industry. One of the main reasons for the subsequent rapid development of the labor-intensive light industry sector was the ample supply of labor from the agriculture sector. According to estimates, the employed population in the secondary industry increased from 15.31 million in 1952 to 232 million in 2012, a net increase of 216.69 million over the span of six decades. The share ratio of those employed in the secondary sector also increased from 7.4 percent to 30.3 percent in the same period, while the share ratio of those employed in the primary sector continued to decline, from 83.5 percent to 33.6 percent for the same period (see Figure 1). It can be seen that the agricultural sector provided a substantial labor supply to the industrial development in China.

Additionally, the labor force from the agricultural sector was of high quality. As a result of consistent attention to education and the sound implementation of the nine-year compulsory education policy across the country by the Chinese government, illiteracy and semi-illiteracy ratios among the rural labor force in China declined from 27.87 percent in 1985 to 4.08 percent in 2010. In 2013, the gross ratio of high school enrolment in China reached 86 percent. These educated laborers entered into the industrial sector in China’s industrialization process and created (massive values?) In 2009, the GDP created by every migrant worker was 23,000 RMB per annum and the total GDP created by the 200 million migrant workers reached 5.7 trillion RMB (Li and Qi 2010).

3.2.2 Agricultural capital provided ample financial support to the development of light industry in China.

Though China gradually removed the “price scissors” in the exchange of agricultural products for industrial products after 1978, agricultural capital still played an important role in supporting China’s industrial development in the form of township and village enterprises (TVEs) and the “price scissors” in land exchanges.

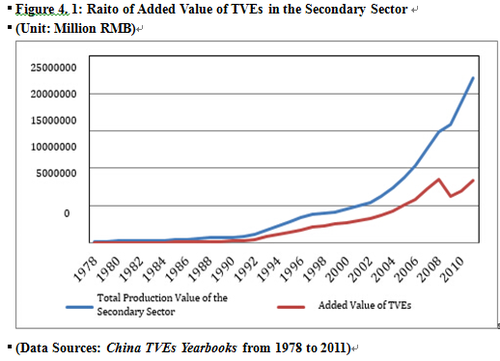

TVEs, a special entity in China’s industrial development, originated and developed in rural areas. TVEs were usually collectively owned and operated by village communities, who were responsible for their profits and losses. Rural land constituted the major source of investment in TVEs as factories were largely built by farmers. Though state-owned banks offered preferential loans to TVEs, much of the initial investment in construction came from the agricultural sector with limited national support. TVEs were then able to use their profits to expand production and import advanced equipment through development and self-accumulation. During later years, most TVEs then became private businesses and raised more support from the agricultural sector. Therefore, agricultural capital from rural areas was the major supporting source for TVE development in China.

In the meantime, industrial development gained a lot of financial support from the “price scissors” in the exchange of rural land, which was collectively owned. In China, the state monopolies were the primary market for transferring rural collective land into urban state-owned land. Starting from the 1980s, demand for land increased along with China’s urbanization and industrialization processes. Rural land then gradually became marketable, but its price was controlled by the state which usually was very low.. As a result, the “price scissors” in rural land exchange flowed to cities and industries and thus became a major contribution from the agricultural sector to China’s industrialization. From 1980 to1999, total 2000 billion RMB (close to 323 billion $US) had been appropriated from rural area through land transaction for industrialization and urbanization (Liu 2001). According to the monitoring data of China’s Ministry of Land Resources, revenues from land transactions increased quickly from 1999, reaching 700 billion RMB in 2006, 1300 billion RMB in 2007 and 960 billion in 2008 respectively. Most of these revenues came from the “price scissors” in exchanging rural collective land and were then invested in industrialization and urbanization. In addition, in order to attract more investment in their localities, local governments usually charged very low costs in leasing out land to domestic and foreign enterprises (Research Team on China’s Land Policy Reform 2006).

3.3 Relatively sufficient supply of food enabled low food price to keep low wages from the industrial sector

There was a relatively ample supply of grains resulted from the implementation of household contract responsibility system and the development and application of agricultural technology. During the end of 1970s and early 1980s, the per capita amount of grain reached more than 285 kilograms and maintained 300 kilograms after that except for the year of 2003 which was 286 kilograms. From 2004, the self-sufficiency ratio of grain in China was kept above 95 percent and exceeded 97 percent in 2013 when the yields of grain were 601.94 million tons (China Bureau of Statistics 2013).

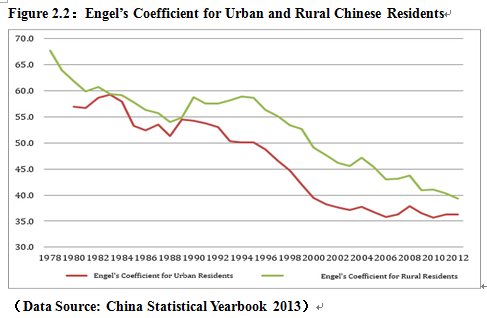

The Chinese government also used other policies to stabilize grain prices. Before reform and opening-up, China adopted the command economy to allocate food. Private business was also excluded from purchasing and marketing agricultural products to maintain price and market stability and enable a supply of grains to urban people at a low price. After 1978, the state had strict control of purchasing and marketing of grains through the establishment of a grain reserve system at central and local levels. China also administered imports and exports of grains through the quota system. All these measures sustained the stability of grain’s prices in China. Over the years, though food price of food was increasing in China, it was kept at a low level when compared with people’s income. As shown in Figure 2, the Engel’s coefficients for both urban and rural residents were declining and were both below 40 percent by 2012.

3.4 The Chinese government supported agricultural development